What could possibly go wrong? A 67-year old politician going on stage at a Libertines gig… in front of 20,000 young people… on a Saturday night in a tough Northern town… in the middle of a general election.

It is 20 May 2017, just over a month since Theresa May shocked the political world by calling a snap election. There are 19 days until polling day. Jeremy Corbyn is in the Wirral. He has just addressed a rally of thousands of Labour supporters on the beach in West Kirby. In nearby Prenton Park stadium, the home of Birkenhead’s Tranmere Rovers Football Club, a music festival is underway. Rumours are buzzing around social media that Corbyn is going to appear with the headliners. “If Corbyn comes out with the Libertines then this could possibly be the best gig ever,” tweets one attendee. “Gonna vote Tory if Jeremy Corbyn comes out with Libertines. Not even joking,” posts another.

As it happens, whether Corbyn will appear is yet to be decided. The idea, devised by a team of young advisors working on Labour’s election campaign, is for him to appear not with the Libertines but during the set of one of the support acts. But the proposal has faced opposition from various quarters. The Special Branch officers assigned to protect the Leader of the Opposition are not happy about the security risk. “That can’t happen,” they told Corbyn’s chief of staff, Karie Murphy, when they learned of the plan.

“Not a problem,” she said.

“So you’re not going to do it?”

“I’m absolutely going to do it,” she replied. “I’ll get private security in Liverpool.”

Labour’s press team has a different concern: the Libertines’ frontman, Pete Doherty. He and his band have been very helpful, but people who are paid to worry about bad headlines are worrying about bad headlines should Doherty, whose reputation precedes him, do something unpredictable. Nerves are allayed when they learn that the singer is running late to the gig.

Then there is the question of the reception Corbyn will receive. What if the crowd boos him? What if they bottle him off? This is Birkenhead, not Glastonbury. A crowd of mainly working class Northerners has paid to get into Prenton Park for a concert, not an election rally.

Ordinarily, any one of these risks would be enough to keep a politician away. But the Labour leadership is doing things differently. If the opinion polls are to be believed, they started the election campaign up to 25 points behind the Tories. There was never any point in being cautious. They have broken every political rule. When they outlined a strategy designed to mobilise young people, non-voters and marginalised groups, all the experts and pundits—and even top officials in the Labour Party—laughed. Yet the gap to the Tories has since halved. Labour is on the up.

Corbyn will do the gig.

“There’s someone special who’s come here to talk to you,” says Jon McClure, singer of Reverend and the Makers, interrupting his band’s set. “Please welcome Mr Jeremy Corbyn!”

The crowd erupts instantly. This is a good sign. There is even the sound of girls screaming. Unexpected.

“Look here,” says Corbyn after 30 seconds of applause, “we’ve got football and music all in the same place.” The crowd has not stopped cheering so Corbyn speaks in short bursts to make himself heard. He has simplified his message for the occasion: “I love football! And I love sport! And I want it for everybody! Those very wealthy clubs in the Premiership, pay your 5 per cent so we’ve got grassroots football for everybody!”

The crowd likes it. Corbyn looks out on thousands of hands raised above heads, clapping. This is going well.

“And it’s also about young people and music,” he continues.

Some way back in the crowd on the right hand side a chant has started. It is just a few singing at first, but it spreads like wildfire. Soon it is audible from the stage.

Corbyn is still speaking. “In every child…”—he repeats himself, competing with the noise and glancing to the origin of the chant—“in every child there’s imagination and there’s hope, and tha…”

His speech stumbles. The chant is louder. The whole front section of the crowd has joined in.

“…and so what I want,” Corbyn persists, “is every school… every school… to have the money for every child to earn… learn… musical instruments.”

They are not listening to him. The chant is drowning him out. Corbyn stops speaking. It is difficult for him to tell from the stage what they are singing. He thinks they might be having a go at him. This could be a disaster. “I’m looking at these guys chanting,” Corbyn will later recall, “and I realise they’re smiling. So I paused and realised what they were chanting.”

The melody is familiar. It is the White Stripes song ‘Seven Nation Army,’ a tune appropriated by fans in football stadiums around the world. But it has never before been sung with these words.

“Ohhhh, Je-re-my Corrr-byn.”

As it dawns on him that they are singing his name, Corbyn feels “quite moved.” For 20 seconds he says nothing as the chant envelops the stadium, getting louder and louder, gaining rhythm as people start clapping along. Sections of the crowd are jumping up and down as they sing it. Some are perched on others’ shoulders, arms stretched up to the heavens as they belt it out. Something magical is happening. From the left to the right, at the front and even right back at the bar, Prenton Park pays musical tribute to the politician who has come to speak to them.

To the side of the stage, the staff accompanying Corbyn cannot stop laughing. They think it is “absolutely amazing.” This is not a Corbyn rally. It is not even a protest. It is 20,000 mostly young music fans. Labour has somehow found itself a leader who can turn up on stage unannounced at a big outdoor concert, and instead of the crowd lobbing pints of beer at him, they chant his name.

“Thanks guys,” Corbyn finally interjects. He tries to press on with the rest of his 5-minute speech. “I’m going to upset the Coral otherwise because they’ll be delayed coming on.” But the chant rumbles on, increasing in volume again as Corbyn winds up. “Thank you for giving me a few minutes, and remember: this election is about you!”

By the time Corbyn leaves the stage, footage of the crowd’s reaction is already setting social media alight. It is one of those spontaneous moments that turns received wisdom on its head. The notion that young people are unreceptive to political ideas is wrong. The notion that Corbyn is universally derided is wrong. The notion that Labour is headed for a crushing defeat is—suddenly a little less certain. One of the staff greeting Corbyn as he comes off stage has been saying for weeks that “something subterranean is going on.” Now it is clear: the ground is shifting.

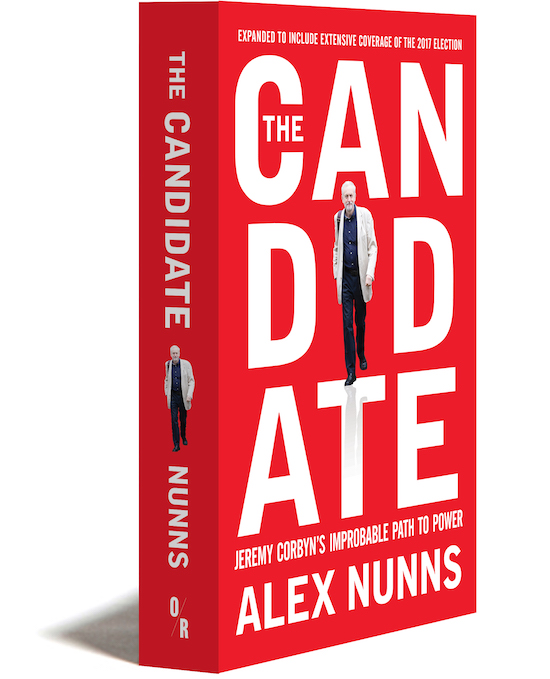

The Candidate by Alex Nunns is published by OR Books. To get 20% off the cover price, use the discount code: OHJEREMY at purchase on the OR Books website