Norman Spinrad has easily the most fitting surname of any science-fiction writer to have yet appeared in print, so good in fact that if he didn’t exist another author would have surely made him up. Spinner of radical ideas and teller of tall tales is the essence of what a science-fiction writer does and is practically part of the job description. I read two of his novels, Bug Jack Barron and The Iron Dream, almost twenty years ago. I thought both excellent but didn’t read any further at that time. Soon other writers occupied my attention, William Burroughs, Nabokov, Pynchon, David Foster Wallace – all of whom occasionally used aspects of science-fiction in encyclopedic works much broader in scope. More recently, however, I began to feel as though I wanted to read some SF books again and, remembering those two Spinrad novels fondly, I decided to investigate his work further. Three months, twelve novels and a handful of short stories later, I still haven’t quite exhausted his bibliography but I am nearing a fuller appreciation of a highly original author, an iconoclast and cultural shaman who, even in his early seventies has lost none of his fearlessness or talent for confronting controversial issues, as evidenced by his 2007 novel Osama the Gun. Despite being printed in French, the novel currently has no English language publishing deal, although it apparently produced a number of ‘foaming at the mouth’ style rejections from American publishers.

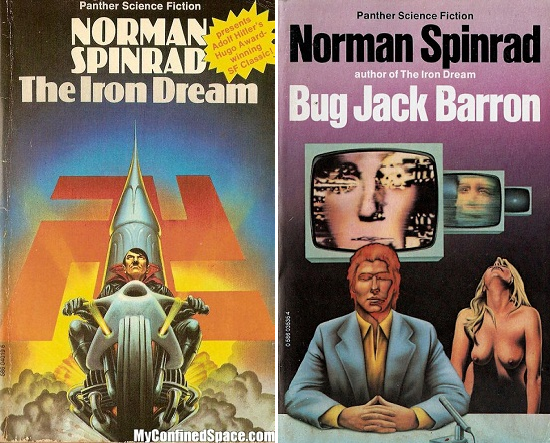

A self confessed ‘anarchist’ and ‘syndicalist’, Spinrad was born in New York on September 15, 1940. He attended the Bronx High School of Science and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree from City College of New York. Spinrad began writing short-stories while at college but it wasn’t until his fourth novel, Bug Jack Barron (1969) that Spinrad’s craft, as well as his notoriety, took a quantum leap. Told in a kind of street-wise late 60s argot that invoked both Burroughs and Kerouac, the novel concerns a hugely popular television talk show host who uses his high profile and media-savvy to defeat the murderous capitalist Benedict Howards and his cryogenic Freezer Utility Bill. Although the language of the novel, sometimes approaching stream of consciousness at the level of individual association, dates it as being from a very specific time in American history, its concerns over the questions developing science raises over issues of life-extension and potential future immortality are far more relevant today that when it was first published. Only last week, all the national newspapers ran the story of the discovery scientists have made regarding the freezing adult skin cells so they don’t age, which can later be turned to stem cells to be used later in life for rejuvenating surgery. Although the papers stated that at this stage, the procedure will most likely only be taken up by ‘celebrities and the very rich’, an actual price is given for the storing of such cells – £40,000. Clearly the fear of death and of aging is something that is always with us, and as technology advances and with it the possibility of indefinitely prolonging an individual’s life, questions as to who will have access to such technology, and what this will mean to the potential for extending areas of personal power, will become even more relevant. Barron’s girlfriend, Sara Westerfield’s first impressions of the Long Island Freezer Complex are, well, chilling:

“Temple, she thought, it’s like an Aztec-Egyptian temple with priests sacrificing to gods of ugliness and praying for alliances with snake-headed idols to ward off the god with no face, and all the time worshiping him with their fear. No-faced death-god, like a big white building without windows; and inside mummies in cold swaddling, sleeping in liquid helium amnion, waiting to be reborn.”

Bug Jack Barron represented a significant attempt to step up the quality of the language used, not that the british authorities saw it that way. Although the sex and profanity in the novel appear tame by today’s standards, its initial publication in Michael Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine led to questions being asked in the House of Commons due to the Arts Council having provided a small grant to the publication. WH Smith refused to stock the magazine and the future of the magazine looked in jeopardy until, as Moorcock relates, the press came to their aid and the attending publicity forced Smiths (and the distributor) to reconsider. The lack of any convincing female characters is undoubtedly the book’s greatest flaw, but this is a fast paced novel that really packs a punch and retains at its centre, a secret that has not lost its capacity to shock – the extent to which a rich man will go to obtain immortality. It is also noticeably, not really science-fiction (apart from the central scientific conceit, which as a lot of critics have noted, doesn’t really make scientific sense anyway) and was marketed at different times as both an SF and a ‘mainstream’ novel. During this period, Spinrad also penned one of the best original Star Trek episodes, ‘The Doomsday Machine,’ in which the Enterprise must confront an alien, planet killing machine on course for the heart of Federation space.

Moving from one controversy to the next, 1972s The Iron Dream utilised the kind of metafictive device Nabokov deployed in Pale Fire, to postulate an alternative reality where World War II didn’t happen and Adolf Hitler moved to the US where he first became an illustrator and then a science-fiction writer. The book is thus presented as a reprint of Hitler’s ‘Hugo Award Winning SF Classic’ Lord of the Swastika. The book won the French Prix Apollo Award, as well as being nominated for a Nebula and the National Book Award, but was banned in Germany for eight years – due partially, no doubt, to its disturbing, yet intriguing cover – before finally being exonerated. The novel took the kind of alternate history postulated by Philip K. Dick in his 1962 novel, The Man in the High Castle, in entirely new directions and examined at a psychological level, the kind of pathology that produced Nazism. Spinrad has said that the inspiration for the novel came from a conversation with Michael Moorcock about the sword and sorcery genre, in which Moorcock revealed that he was able to churn out such stories so easily as he simply took pre-existing mythic structures and pumped them full of Freudian imagery. Having begun by asking himself how it was that Hitler came to power, Spinrad saw the same kind of process at work in the rise of Nazism. As he explains in a 1978 interview in Amazing Stories, Spinrad says that he came to understand that “Hitler came to power by manipulating Jungian archetypes and existing psycho sexual structures in people’s minds.” Taking further inspiration from Joseph Campbell’s examination of the cycle of mythic elements that repeat throughout different cultures, The Hero With a Thousand Faces, Spinrad’s novel works on three distinct levels. First as a satire of a certain kind of SF novel that Spinrad obvious felt deserving of relegation to the genre ghetto. Secondly as an attempt to explain Nazism in a way that made sense to the author himself. Thirdly, it can be seen, as some French critics have suggested, from the perspective of the Anti-Oedipus theory, which suggests that people are manipulated by the investment of desire, by images which focus libidinal energies into place. Taking into account the unlikely possibility that anyone may still consider the novel to be a ‘Nazi book’, Spinrad added an afterword by fictitious authority, Homer Whipple, noting the ‘abundant evidence of mental aberration on the part of its author.’

The Mind Game (1980) is said to have been inspired by Spinrad’s attempt to interview fellow SF writer, and head of the Church of Scientology, L Ron Hubbard. Although he was unable to gain an audience with Hubbard, Spinrad’s attempt nevertheless drew the attention of his loyal minions and the author found himself the uncomfortable object of their scrutiny for some years. The novel, which was also marketed under the title The Process, takes the form of a taut, fast moving thriller. Having completed Lawrence Wright’s revealing, yet not entirely unsympathetic book about Scientology, Going Clear, just prior to starting this book, I found Spinrad’s portrayal of Transformationalism, with the fictitious SF writer John B. Steinhardt at it centre, to be utterly compelling. Although the book is narrated from the point of view of protagonist Jack Weller who is pursuing a wife who has been subsumed into the cult, Spinrad does not lose his sense of empathy with those who might wish to seek some new form of enlightenment and even depicts the guru at its centre in charismatic, yet ambiguous terms which make him both larger than life and more complex than if he were represented as a merely villainous enigma. John B. Steinhardt is depicted as a heavy drinking philosopher with a real thirst for furthering mankind’s evolution as well as a clear understanding of the nature of the cult at whose centre he resides. By the time he and Weller come face to face, it already clear that the former failing director has benefited considerably from his exposure to the cult despite his many personal misgivings. Steinhardt surprises him still further by asking Weller to work with him on a series of films that will act as ‘a spanner in the works’ after his own death. In putting such words into his fictional guru’s mouth, Spinrad displays a keen understanding of what happens to ‘cults of personality’ after their leaders pass on. He also cleverly highlights what must be a perennial problem for anyone involved in any sort of institutionalised form of personal development, namely how to hold onto one’s creative abilities in the face of any form of psychological ‘processing’.

The following two novels, The Void Captain’s Tale (1983) and Child of Fortune (1985), represent the pinnacle of Spinrad’s achievements as a science-fiction writer and stand as truly unique texts by any genre’s standards. Written in the kind of polyglot admixture of words that Russell Hoban and Anthony Burgess used to such great effect in Riddley Walker and A Clockwork Orange respectively, The Void Captain’s Tale relates the disastrous saga of captain Genro Kane Gupta’s burgeoning obsession with his pilot, Dominique Alia Wu. The ship’s drive method is derived from the remnants of a device which belonged to a conspicuously missing alien race, referred only to as ‘We Who Have Gone Before,’ which during flight triggers orgasm in the pilot as an intermediary stage between a form of cosmic consciousness. Dominique Ali Wu has dark desires and scant regard for the flesh that contains her consciousness. The honored passengers exist during flight in a Floating Cultura, a plush environment curated by the most respected of artisans of all artistic persuasions, which essentially serves as a distraction from the fact that outside of the vessel’s walls is the only true reality, the void at the center of all (a striking metaphor whose truth resonates beyond its future setting). Told in a futuristic ‘sprach’ that has more of a cold, germanic quality to it than its ‘sister’ accompaniment, the novel is very dark, contains lots of writing about sex in a way that I have never seen it contextualised before and has a kind of nihilistic, disturbing mysticism that combines the dread of HP Lovecraft with the mind bending koans of Zen Buddhism. It is a truly unique piece of writing and if you’re not put off by my description of it, you should read it immediately.

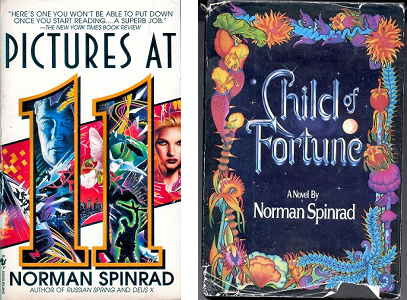

The ‘sister’ piece, 1985s Child of Fortune, is set in the same universe but is an autobiographical tale concerning the ‘wanderjahr’ of Wendi Shasta Leonardo, and delineated in a ‘sprach’ of a more latinate and Italian future tongue than its predecessor. The cover of the book has iridescent-hued alien flowers growing around the margins and the title in kind of font normally associated with more ancient tales, like something suitable for the Tales of the Arabian Nights. Timothy Leary is quoted on the back, calling it: ‘A Homeric space voyage, a Joycean interstellar trip, a Huck Finn saga of humanity’s next adventure.‘ A large section of the book concerns Wendi and her then paramour, Guy Vlad Boca becoming lost in the vast, psychedelic flora-infested jungles of Belshazar and witnessing humans turned effectively into pollinating drones by the innumerable variety of psychotropic flowers that exist there. It also goes further than any of Spinrad’s other novels in declaring a love and celebration of the tale-teller’s art, with Wendi eventually becoming a ‘ruespieler’ (story teller) after much reflection on the shamanic and eternal aspects of her art. The female protagonist is affectionately rendered and it came as no surprise to me that Spinrad thinks of this as a favourite amongst his novels. These two are really for the psychonauts among you out there and those of you who knew immediately what it meant when you read William Gibson disparagingly refer to the world of the body as ‘meatspace.’

Gibson appears on the back of Spinrad’s subsequent novel, 1987s Little Heroes, which could be seen as his take on the cyberpunk genre, although in reality any of the elements that could be perceived as such (like the wearing of ‘wire’ equipment to deliver drug-like effects) existed in earlier Spinrad work anyway. Little Heroes concerns a near future where both the economy and the music industry are in severe decline. The economy is tanking because ‘we wrote the biggest bounced cheque and passed it off on ourselves’ and an MTV-like corporation is attempting to perfect the process of creating artificial pop stars. From the very 80s-looking cover and particularly the descriptions of the music acts there is a certain ‘cheesy’ quality that I personally found enormously endearing. The characters are all well drawn and sympathetic and the plot has an innate sense of its own momentum despite the novel’s considerable heft. It’s like a cartoon or a music video in some respects, but a glorious one, with a large side-helping of anarchist sentiment.

Pictures at 11 (1994), Greenhouse Summer (1999) and He Walked Among Us (2003) marked a shift towards a more ecologically inspired perspective. Whilst Pictures at 11, which concerned a group of Eco Terrorists take over of a Los Angeles TV station, displayed the usual fast moving plot and compulsive readability despite being entirely set at the hostage scene, He Walked Among Us was a different beast altogether. I think it would be fair to say that Spinrad is an author who has not stuck to any one formula and has taken many risks, not all of which paid off. At over 500 pages, its one of the largest of his books and also one of the less easy going. It also insults SF convention goers in some of the books funniest moments. Tim Leary almost makes an appearance:

‘Norman Spinrad once told Dexter that he had arranged to meet Timothy Leary at a con hotel to go out for dinner… ‘How come you didn’t show up, Timothy?’ Spinrad asks Leary a few days later. ‘…I was there for about half an hour but I couldn’t find you, and that was about all I could take’ says the veteran guru of a thousand acid trips. ‘Those people were just too weird for me.’

Spinrad received afurther, psychologically revealing mention when we are told by the guru-like figure of author George Clayton Johnson (who wrote several classic original Twilight Zone episodes):

‘Norman Spinrad once showed me a medicine wand that he carved on acid… he extracted this totem from the rough shape in the natural wood, and was moved to incise in the stick below it the double helix.’

A lot of the novel is metaphysical discussion about what can be said to exist between a potential future and the present which spawns it. Combined with the fact that the main protagonist (a deadpan comedian sent back from future in order to prevent it) is deliberately unconvincing and not particularly likeable, this doesn’t always make for easy reading. As an investigation into the nature of belief and the potential for the human imagination to intercede against the direst of possible futures, however, its hard not to admire what its trying to accomplish.

Finally, I finished Osama the Gun yesterday, at times swept along by the pace of the narrative, waiting for something truly terrible to arrive and by the end I was not disappointed, although I certainly was appalled. Spinrad tells the tale entirely from the perspective of the young Osama, born to relative prosperity in a future Califate state established in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, who trains as a secret agent initially so that he can pursue his idea of forbidden female fruit but who becomes accidentally embroiled in a series of events that eventually paint him as the mythic terrorist ‘Osama the gun’. Spinrad has gone on record as saying that he wrote this as a response to 9/11 but it is clear from this that his own contrary brand of idealism demanded he write something from the terrorist’s perspective. I found it to be very effective and thought provoking, whilst simultaneously understanding why it has very little chance of being picked up by a mainstream American publisher. Osama comes to understand that it is the ‘soulless’ evil of the automated, robotic US war machine that is the greater Satan, and it’s hard for the reader to disagree with that. When it comes to the ending, however, a continual game of brinksmanship leads to a scenario that can only be described as appalling from whichever perspective it be viewed. If Spinrad wanted to show us where that sort of madness can eventually lead, then this is certainly a case of mission accomplished.

I end this piece, simply running out of space. Norman Spinrad is the author of over 20 novels and around 60 short stories. I have on my desk before me another two unpublished novels that Spinrad sent to me, Welcome to Your Dreamtime, which the author claims will teach readers the concept of lucid dreaming, and Police State, a non-SF work which lifts the lid on conditions in New Orleans post-Katrina. Osama the Gun is available in English as an e-book. 17 of Spinrad’s books which have long been out of print have recently been re-issued by ReAnimus Press. For the last six years, Spinrad has been giving interviews to a documentary director, for a film which will hopefully soon be completed. Spinrad celebrated his 73rd birthday last Sunday as guest of honour at the LoneStarCon world science-fiction convention in San Antonio, Texas.