CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

Unhappy Birthday

BY 1987, THE SMITHS WERE NO longer the bright young hopes of British pop, but seemed locked at a curious crossroads. Since their emergence, five years before, time and changing fashions had decimated many of their contemporaries. Triple chart toppers Frankie Goes To Hollywood had sought a new stage in the Royal Courts of Justice; pin-up pretenders Wham! had committed pop euthanasia; Spandau Ballet had long been exposed as more style than substance; Dexys Midnight Runners had taken one sabbatical too many and their scintillating Don’t Stand Me Down was criminally ignored; Duran Duran had outgrown their fans, or vice versa. Only The Pet Shop Boys maintained some of the glitz associated with early Eighties pop, while sustaining the interest of their audience with regular dashes of ironic wit. A large proportion of chart pop was about to fall into the hands of a relentless production team, whose run of successes would make previous plutocratic outfits like Chinn/Chapman seem impoverished by comparison. Stock, Aitken and Waterman sounded like a City firm of solicitors, but would soon become synonymous with instantly breezy, innocuously engaging, daytime radio pop. Ironically, their first major success had been with Morrissey’s soul mate Pete Burns, whose group Dead Or Alive had enjoyed a memorable number one with the production team’s pulsating ‘You Spin Me Round’, back in 1984.

On the LP front, The Smiths looked on dispassionately at respected rivals Echo And The Bunnymen, whose support base and sales were insidiously dwindling. Other ‘long termers’, such as New Order, Depeche Mode and The Cure, were all progressing in their various artistically uncompromising ways, and steadily reaching new audiences. On a different level, there was U2, lately canonized as The Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin of their generation. They had achieved wealth and international acclaim with an organizational efficiency and managerial acumen that was exemplary in its simultaneous pursuit of commercial and creative autonomy. Beneath the Dublin quartet was a burgeoning band of stadia careerists, personified most plausibly in the bombastic vacuity of Simple Minds. The appeal of this deceptively alluring brand of pseudo-intelligent pop/rock was further demonstrated by the otherwise unremarkable Tears For Fears, who had twice reached number one in the USA.

There was good reason for predicting The Smiths’ elevation to the rock super league. The music press polls testified to the passion of their following, which was demonstrably increasing. The impact of The Queen Is Dead and ‘Panic’ on the charts emphasized that the masses were ready to embrace The Smiths as both a rock band and a pop group. More importantly, the Mancunians appeared to have the artistic arsenal to produce regular, quality product. An annual album, quarterly single and well-paced touring programme would surely enable them to expand their market and transcend the self-imposed limitations that had accompanied the Rough Trade years. Of course, none of this could be achieved without a radical shift in policy and business organization. Once again, The Smiths urgently required an experienced manager who could represent them forcefully during this new phase of their career.

Ken Friedman hailed from San Francisco, where he had attended the University of Berkeley and later worked for the hard-nosed promoter Bill Graham. After switching to the management division of Graham’s organization, he oversaw the affairs of various visiting UK acts, including Simple Minds. Personable and persuasive, Friedman decided that he had the talents to succeed as an independent agent and set up his own company.

During the Bill Graham years, he had built up some good contacts but, despite his undoubted friendliness, affability and charm, Ken was not universally loved. Former Smiths’ caretaker manager Scott Piering, who had crossed swords with Friedman as a promoter, was waspishly contemptuous of the man and responded with an unrepeatable stream of slanderous abuse at the mere mention of his name. By contrast, Piering’s managerial successor, the more reasonable Matthew Sztumpf, found Friedman engaging and enthusiastic, but still spotted signs of over-reaching vulnerability. “Ken got a bit clever and set up on his own, at which point things started working out not so well,” Sztumpf observed. “He lost Simple Minds. He was always good at attracting artistes, but less good at keeping them.” The thistle-tongued Piering piercingly punctuated this point. “He was really quite a lightweight for all his talk,” he sneered. “His place was littered with ex-bands.”

The worst you could say about Friedman was that he was a fighter as well as a lover and had a tendency to overreach himself. In the music business, these were hardly demoniac traits, but commonplace virtues. Sztumpf had first introduced Friedman to The Smiths during their 1985 US tour of America. The San Franciscan immediately ingratiated himself with Morrissey, whom he took on a safari of book shops. After hanging out with the group and winning their guarded approval, he found himself unexpectedly championed by Sztumpf. Matthew’s intention was to form a transatlantic management company, with Friedman representing all his acts in the USA, including Madness and The Smiths. The grand plan failed to materialize, however, and before long Sztumpf joined the ranks of jettisoned Smiths managers. Friedman stayed distantly in favour over the next year, a period in which he organized UB40’s memorable trip to the USSR and generally enlivened their dour profile. For a time, he seemed a likely candidate to oversee Echo And The Bunnymen, but preferred the more challenging prospect of taking on The Smiths. After consulting Sztumpf about his chances, he gently sought their hand. When Morrissey considered the moment to be right, he despatched Marr on a Friedman finding mission and arranged a meeting. Friedman was excited about the prospect of working with a group of The Smiths’ critical stature and was impressed by the apparent scale of their ambition. The enterprise was encouraging.

In January 1987, Friedman emphasized the degree of his commitment by transferring his operation to London. Against the odds, he even persuaded Morrissey to put his name to a two-page letter of agreement by which the American was officially appointed manager. Momentarily, it seemed that The Smiths had finally found a figure who had sufficient enthusiasm, belief and industry to convince them to tour the world. “Ken was younger and hipper than anyone else who tried to manage them,” Grant Showbiz observed. “You could hang out with him. He’d been around and was pretty cool. I thought he was a groovy guy.” Although Morrissey seemed similarly taken with the American, his true feelings were at best ambivalent. ”Morrissey’s relationships with people became far more private as time went on,” Grant says. “He would take you aside one day and make fun of somebody and the next day he’d be doing whatever they said. By that time I was spending a lot more time with Johnny.”

The rise of Friedman coincided with the release of the group’s thirteenth single, ‘Shoplifters Of The World Unite’. Although less commercial than their recent fare, the song climbed to number 12, a sure indicator of their popularity at the time. There was even some minor controversy when a Conservative MP took the song title too literally and attacked The Smiths in print. Another gift for source hunters, the track is a pick and mix of borrowed half-lines, culminating in what sounds like an adaptation of Rickie Lee Jones’ ‘The Last Chance Texaco’ in which she sang: “He tried living in a world and in a shell”. In Morrissey’s fictional universe, those sentiments are transformed into an impenetrable world weariness from which he draws strength: “Tried living in the real world instead of a shell/But I was bored before I even began.” Even the allusive title sounded like a cross between a paraphrased Marxist dialectic (‘Workers Of The World Unite’) and an anti-romantic riposte to David & Jonathan’s 1966 hit anthem ‘Lovers Of The World Unite’. Always an opponent of the traditional love song, Morrissey’s subversion is evident from the song’s strange opening lines. “Learn to love me, assemble the ways” he sings, as if love was purely a mechanical process, learned from a car manual or constructed on an assembly line by an automaton. What is the ‘listed crime’ that the narrator acknowledges as his sole weakness? The innuendo is undeveloped, a familiar Morrissey trick. There’s a furtive, playful quality at work here that permeates his songwriting. It recalls the narrative mystery of ‘The Hand That Rocks The Cradle’ and those characteristically dramatically discreet or evasive one liners such as “oh well… enough said” in ‘I Know It’s Over’. Marr’s non-melodic E-chord arrangement paradoxically enhances Morrissey’s opaque lyrics in what is surely one of their unlikeliest hit singles.

The flipside, ‘Half A Person’, was more straightforward and attractive, but equally revealing in its evocation of Morrissey’s strangely obsessive youth, when fleeting figures could secretly inspire irrational romantic devotion. Morrissey was a character who always required idols and the apotheosis of an ordinary but attractive acquaintance was as common as the idolization of a star. Tellingly, he went out of his way to stress the song’s autobiographical aspects to reporters, while also revealing nothing specific. There are some fine comic moments in the song, not least when Morrissey offers the hesitant, pause for effect, “Y… WCA”. The effect is to encourage the listener to consider whether he is again playing gender games, using a female narrator, or simply coyly avoiding (while simultaneously drawing attention to) the YMCA tag, with its Village People gay connotations. Much of the song’s power comes from Morrissey’s expressive vocal, which is both vulnerable and full of adolescent insecurity. There is a wonderful pathos in the admission that the singer’s whole life could be summed up in this teenage drama of shyness and solitude. The closing refrain ‘The Story Of My Life’ echoes the title of Michael Holliday’s 1958 chart-topper. Holliday’s life had ended in suicide which somehow makes the words even more chillingly appropriate. In keeping with its alluringly modest air, the song’s melody was conceived in a moment of quiet inspiration. “We just locked ourselves away and did it,” Marr recalls. “In the time it took to play, we wrote it.”

A third track, ‘London’, was featured on 12-inch copies of the single. Built round a relentlessly driving riff, echoing the movement of a train, the song documents the ambiguous feelings of a youth fleeing the north for the bright lights of the capital. The scenario recalls the closing scene of Billy Liar, although in Morrissey’s re-enactment the roles are reversed, the girlfriend is left behind, and the troubled protagonist takes the train to Euston.

On 7 February, The Smiths gave what was to be their last live performance, at Italy’s San Remo Festival. They were scheduled to play before a large television audience who had gathered enthusiastically to witness the cream of Eighties British pop. The Smiths were placed on a revolving stage, alternating with a battalion of pop idols including Spandau Ballet, Paul Young, The Style Council and The Pet Shop Boys. It was one of those strange, but wistful moments in pop. Exactly 20 years and two weeks before, Mick Jagger had shocked the elders of British showbusiness by refusing to allow The Rolling Stones to mount the revolving stage at the close of Sunday Night At The London Palladium. Now, Morrissey was unwittingly about to repeat that memorable protest. A technical hitch in the sound meant that The Smiths had to reprise their act and, not surprisingly, the temperamental singer declined to perform. Friedman was forced to coax the star into reconsidering with a laudable display of business logic. Much to the amazement of the assembled company, Morrissey relented. Upon boarding the revolving stage, The Smiths concentrated on recent material and played a sharp, five-song set, including ‘Shoplifters Of The World Unite’, ‘There Is A Light That Never Goes Out’, ‘The Boy With The Thorn In His Side’, ‘Panic’ and ‘Ask’. It was amusing to consider that the group were closing their performing career as part of a good, old-fashioned pop package revue.

Surprisingly, the San Remo Festival saw The Smiths looking more relaxed and sociable than on any previous occasion abroad. “In the past, they’d go into the dressing room with the door locked and nobody would wander in to say hello or have a beer,” Friedman says. The new manager encouraged them to appear less aloof and argued that it was healthy to “hang out, meet other musicians and have fun”. Morrissey, who had once claimed that he would never do anything as vulgar as having fun, said little but allowed the old and new pop aristocracy within his presence. He was even seen chatting to the animated Patsy Kensit. Marr, after years playing the role of a Smith, was even more amenable to the Friedman school of sociability and welcomed the opportunity to break down artistic barriers. The roguish Rourke, always the Joker in the pack, was already making fun of a fellow pop star. “We went out to a disco one night and Spandau Ballet were there. I was really drunk and I went up to Steve Norman and I was calling him ‘Plonker’. That was his nickname in the NME. I was calling him Plonker Norman and he got really upset. That was when we were all drinking a lot and doing a lot of other things to excess.”

Morrissey admitted that he felt more bemused than offended by the pop bonhomie he encountered in Italy. “It was really intriguing to me,” he explained, “because we’d never really mixed with pop stars before, and most of what they did, I didn’t understand.” One of the more memorable encounters during the visit was between Morrissey and Bob Geldof. Having traded media insults with the Band Aid organizer over the years, the Mancunian was visibly embarrassed when Geldof entered The Smiths’ trailer, but Friedman’s excited affability calmed hidden tensions. By the end of the evening, Morrissey’s reserve had melted and he appeared to be thoroughly enjoying himself. “I don’t know whether he got laid,” Friedman mischievously suggests, “but he had a really good time.” For Friedman, the San Remo Festival represented a major breakthrough in his relationship with Morrissey, but one that would not last.

One week later, The Smiths undertook some promotional appearances on Irish radio and television. During an interview with Dave Fanning on Radio Eireann, Morrissey damned pop videos and championed the cause of minor league, cult fame. “I don’t want The Smiths to be a huge, untouchable mega group,” he declared. “I don’t want that to happen, and it could happen. I’d rather just make the records and go home . . . I’m quite happy in my Smiths box . . . I don’t want to venture outside the garden gate and be this multi-talented finger in every pie. I don’t like multi-talented people.” Given Marr’s recent penchant for ‘multi-talented’ session work and Friedman’s hopes of reaching a wider audience, Morrissey’s words seemed particularly pointed.

The vexed question of a worldwide tour remained on the agenda over the next few months, but Morrissey refused to commit himself unambiguously. Meanwhile, it was slowly becoming clear that Friedman was not the ideal manager for Morrissey, although, like many others, the San Franciscan was alternately fascinated, baffled and frustrated by the singer’s mercurial temperament. “Morrissey was really indecisive,” Friedman says. “He’d make a decision, then just completely change it and not be able to deal with the consequences. So he’d go away and unplug the phone.” The American had a novel, if practical, way of dealing with this problem, which amused those closer to Morrissey. Stephen Street remembers a recording session during February when Friedman presented the singer with an answerphone. “He looked at it and you could tell he had no intention of plugging the thing in. At that point, Ken was trying to make Morrissey more responsible and reply to his phone calls. He said, ‘It plugs in! You don’t have to answer the phone if you don’t want to.’ But Morrissey was dismissive. I think, even at that time, he’d decided that Ken wasn’t the manager for The Smiths.”

Friedman persevered, but found it difficult to persuade Morrissey to play along. “The problem is, he can’t very easily deal with the impact he has on people. He’s afraid of success, like a lot of English people. I don’t know what it is. To us, in America, it’s what you achieve – everybody wants to be a millionaire or president or whatever. What I found baffling in England was that people didn’t really want to make it; they were so embarrassed about it. Morrissey had that attitude more than anybody I’d ever known.”

Friedman’s quizzical attitude towards Morrissey’s psychology indicated how divorced he was from the old values of Smithdom. Even at his most sympathetic, the manager embodied a traditional business-orientated American outlook that was worlds removed from Morrissey’s parochial insularity. Yet, it would be unfair to suggest that Friedman was unsympathetic towards The Smiths or crudely insensitive to their maverick ways. Clearly, one of the reasons he chose to manage them was because of their originality, a view expressed in his appreciative contention that they were “such a special group, such a phenomenon that it must be documented; there’ll be a whole chapter on them in the history of British popular music, if not pop music.” These were not the words of a philistine.

What Friedman had not bargained for, however, was Morrissey’s indecision, amnesiac caprice and rapid plunge into disillusionment over the question of mounting a serious challenge on the worldwide stage. For Marr, Friedman represented a logical way forward at a time when The Smiths sorely needed cogent direction and a new game plan. Such thinking was ultimately anathema to Morrissey who effectively rebelled by retreating. Old dogmas soon reasserted themselves with a vengeance.

…

The character, as opposed to the music, of The Smiths owed much of its philosophy to the precepts of the English punk era, when DIY enthusiasm and anti-superstardom were regarded as the true antidotes to stagnation. In signing to Rough Trade, eschewing videos and championing the industry plagued 45-rpm single, The Smiths had valiantly challenged the prevailing system, while retaining enough arrogance and self-belief to convince themselves that they were, in pop terms, major historical figures. The Smiths were never really shy of success, they just liked smashing through hurdles, and when they grew weary of self-imposed restraints, EMI beckoned. Morrissey, however, was remarkably ambivalent about success, not to mention life. He demanded, craved and expected recognition, and was constantly alert to the presence of imaginary financial predators. In certain cases, he even created them. Yet, the quality of fame was more important than the actual record sales or concert receipts, just as the paranoia about money and small-time exploitation was subservient to a greater fear of losing control. Compared to the parsimony of Ray Davies or Chuck Berry, Morrissey was largesse incarnate, but, in certain respects, he shared their self-destructive ways. The cancelled tours, abandoned appointments and sudden retreats testified to a character whose caprice ruled his nature, art and purse strings. He was, and probably still is, unmanageable in any long term sense. The reins of power and trust could never be reft from his suspicious hands.

Normally, Morrissey would have won the support of his partner in determining such a crucial issue as the group’s managerial future but, on this occasion, Marr resisted. He felt that Friedman’s strategy was sound and, more importantly, refused to surrender to the self-generated chaos that had so often threatened to engulf The Smiths. “Morrissey didn’t want to continue with Ken,” Marr remembers. “I think he was right to do that, but I didn’t want everything to move back to my house as headquarters and for the two of us to sort out the band again. I’d just had enough of that. There was no way that I was going back to taking care of the group. By that time, there was an unhealthy situation with Rough Trade, and there was no way that I was going to take that on board again while making an LP.”

Friedman was in an unenviable position: he wanted the support of Marr and Morrissey, but effectively found himself managing half the partnership during their final phase. In this respect, he was at least more fortunate than his predecessors. For the first time, Marr was unwilling to sacrifice an employee in order to keep Morrissey sweet.

While Morrissey and Marr were busily disagreeing over the question of management, Mike Joyce briefly took time out to help some old friends and rivals. A new group, provisionally titled The Thin Men, were rehearsing in Denham, and Joyce was invited along to contribute to their demos. The miniature supergroup boasted a line-up consisting of ex-Hamsters vocalist Moey (Ian Moss), his guitarist brother Neil (from The Frantic Elevators) and Fall alumnus Marc Riley. It was a pleasant break for Joyce, who retained the capacity to chug along and avoid the higher politics that threatened the longevity of The Smiths.

One problem that they could not make disappear was the ongoing dispute with Craig Gannon. Since his leaving in 1986, and even into the New Year, there had been sporadic bulletins issued by Rough Trade’s press officer Pat Bellis, which chipped away at his credibility. “There were times when he didn’t turn up for rehearsals,” said one, while another alleged that “they were meant to be on Top Of The Pops and he just wasn’t around, he disappeared. That was the final straw.” Gannon elected to maintain a discreet silence at the time, not wishing to involve himself in a slanging match. Six years later, he told me: “I was at every rehearsal that The Smiths ever did while I was with them and to say I missed any is rubbish. One report did state that the final straw for my future in The Smiths was when they were supposed to do Top Of The Pops and they couldn’t find me. There was no way that they couldn’t find me, if anyone had tried to get in touch with me. They would have done the gig anyway, even if they couldn’t find me.” Ironically, it was Gannon who was having trouble contacting Marr, who still had some of his equipment at his house. Arranging its collection was made more difficult now that Marr had changed his phone number for seemingly the umpteenth time.

In contrast to the statements issued to the music press by intermediaries, Marr attempted to put a more positive, diplomatic spin on Gannon’s departure. Explaining his decision to Hot Press, he said: “I felt that I began to get very complacent in my guitar playing and that’s why we asked Craig to leave. There was no kind of animosity at all because we’re still friends with him but it was just that his presence didn’t do anything dramatically for the group creatively so we asked him to go.” Marr’s ameliorating PR may have been intended to calm troubled waters but the suggestion that everyone was “still friends” sounded disingenuous, to say the least.

Since leaving The Smiths, Gannon had teamed up with Morrissey’s former Stretford associate Ivor Perry, to form The Cradle. Their manager, John Barratt, took the guitarist to London solicitors Russells where, with the assistance of Legal Aid, he pursued his case against The Smiths. At one point there was a glimmer of a settlement when Friedman was despatched to negotiate but, according to Barratt, the monies on offer were deemed derisory and the conflict continued. Barratt, who had no love for Johnny Marr, was never likely to be fobbed off easily. When Friedman countered that Gannon had merely been a session player with The Smiths, the garrulous Barratt terminated the conversation. “See you in court” were his final words.

By now, Morrissey and Marr knew they had a fight on their hands. “We didn’t expect it,” Marr later told me. “He played on the record and should have been paid. Simple as that. Because he asked for more, everything became a court case.” And what of the monies for the US tour? “Again, if we could have got our heads together, he could have been paid and we wouldn’t have felt taken advantage of. The fact that we wanted to pay him wasn’t at issue. The issue was that he was saying we’d agreed on more. He said that we’d agreed to pay him some ridiculous fee that we’d never have paid anybody.”

Gannon’s father, who was hurt and indignant about the way his son had been treated, duly told solicitors, “What he wants is what he earned. Nothing more and nothing less. He wants what he was promised and what he should have earned. We’re not asking for any more.” Gannon Snr maintains that Craig was a reluctant litigator forced to fight for his rightful due. “There was no way that Craig wanted to get into conflict with anybody. Not for a minute will he hear anything said [about The Smiths]. If I try to rubbish them, he doesn’t want to know. He would never say anything bad about them. He’s a very loyal lad. I’m obviously a lot more worldly wise and I wouldn’t have taken the same tack but, even now, he’s loyal to them.” It would take several more years before Craig Gannon finally secured an out of court settlement with a payment of £44,000.

The political differences over money, management and career direction were temporarily swept aside as the duo united to complete their outstanding commitment to Rough Trade by recording one last album. EMI had unsuccessfully attempted to buy the rights to the forthcoming work, but Geoff Travis would not be swayed. Friedman privately felt sympathetic towards the independent king, who suddenly found himself left out in the cold. “I like Geoff a lot; I liked him a lot then,” he stresses. “I thought he was treated very unfairly by the group. I always did. He knows that. Geoff could never relate to Johnny or, to put it the other way, Johnny couldn’t relate to Geoff. I think they genuinely didn’t like each other, whereas Morrissey and Geoff had a real love/hate relationship. Geoff was really enamoured of, and almost obsessed with, Morrissey.” Even after signing to EMI, Morrissey naturally felt that Rough Trade should show the same old fawning appreciation of The Smiths. “He still expected Geoff to treat him like he’d treated him before, like royalty,” Friedman concluded.

Surprisingly, Travis kept faith with Morrissey and, as the year progressed, he became more actively involved in the singer’s complicated administrative affairs. Increasingly, his role resembled that of a quasi-manager. Mysteriously trusting to fate, or Morrissey caprice, the Rough Trade founder had not quite capitulated to the EMI signing. When questioned about The Smiths’ impending departure by Craig Gannon’s manager John Barratt, Travis pointedly refused to concede its inevitability. “Up until the end I think Travis still felt he could keep Morrissey on Rough Trade, or even The Smiths,” Barratt argues. “It was common knowledge that they’d signed to EMI, but all he said was: ‘We’ll see.’ I believe he still harboured hopes that somehow they would get out of it in some bizarre way.” Travis had seen enough of The Smiths to realize that nothing was ever certain until it happened. Morrissey had signed to EMI while still under contract to Rough Trade and who was to say that he wouldn’t recklessly reverse that arrangement at a moment’s notice?

Unfortunately for Travis, Morrissey gave no clues of any second thoughts about signing to a major label. On the contrary, The Smiths were eager to begin work on a new record and wave away their remaining commitments to Rough Trade at the earliest opportunity. The new era with EMI was now a kiss away, and the lucrative prospects awaiting them effectively thrust minor disagreements into the background. Technically, The Smiths could have hastened their departure from Rough Trade still further by presenting the company with a perversely uncommercial work, instrumental album or back-stabbing ‘experimental’ piece in the vein of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music. Instead, they took the project seriously. Marr’s attitude as he set out for the studio was to try something different. As a keen music fan, he was growing weary of The Smiths’ awesome legacy in influencing a new generation of indie label guitar groups. “It just became a bit of a pain,” he told me. “I’d turn on night-time radio and hear this jingle-jangle four piece guitar band from Scotland with their fringes and some girl squeaking about running through the flowers. I hated the musical climate. I thought there had to be a way forward.” Increasingly, Marr convinced himself that The Smiths were in danger of being knocked off their perch by some yet-to-be discovered assailants. After five years, their next challenge would be to avoid stagnation and stylization.

In March 1987, The Smiths arrived at the Wool Hall, near Bath, to record their final studio album for Rough Trade. With Morrissey due to arrive the next day, the three Smiths and producer Stephen Street had a late night musical dress rehearsal. For the most part, the atmosphere was convivial but Marr seemed in a playfully confrontational mood. “The first night in the studio they all got a bit drunk,” Stephen Street recalls. “I can remember bashing away at a DX-7 synth keyboard and the drums and bass were playing at the same time. Johnny was really out of it. As he admitted during the US tour, he’d taken a little liking for brandy and was getting a bit out of order. I can remember him shouting, ‘Here, Streety, you don’t like this, do you? You want us to sound jingle-jangly, like the good old Smiths days.’ You could tell there was tension there. It was definitely, ‘You don’t like it do you? We’re going to do this!’” There followed a musical interlude unlike anything Street had previously encountered at a Smiths session. “There was no holding it together. It was like a dirge. You really felt Johnny was pent-up. At this point, he fell on his back and the keyboard went crashing to the ground. I was sitting there trying to keep cool and telling myself: ‘It’s going to be OK. It’s the first night in the studio and they’ve got to leave a bit of tension out. When Morrissey gets in tomorrow, we’ll start doing it.’ But it was a bit strange.”

Following Morrissey’s arrival, the recordings proceeded relatively smoothly and, despite some niggling moments, the old camaraderie was still in evidence. “There was no musical tension,” Street stresses. “Johnny and Morrissey were fine in that respect. We had a really happy time and it was party night most nights… Andy was fine… He seemed to be a little more sprightly. They were happy and having a great laugh. It wasn’t bad at all.”

"The sessions were positive,” Mike Joyce reiterates. “Speaking first and foremost as a player, the relationship between the four of us at that time was the healthiest it ever was. We were all getting out of it with the ales. Things were getting quite crazy at times, but that was the beauty of The Smiths – the craziness. A lot of people didn’t realize how barmy it got.” When Morrissey retired to bed, the drinks would come out and a new soundtrack was unveiled with music courtesy of Sister Sledge, Prince and, improbably enough, Spinal Tap.

Beneath this easy-going surface, Marr nevertheless detected subtle changes in the old Smiths’ dynamic. As he later admitted: “I’ve got loads of photos and loads of video footage of us making the album. You can see us talking and having a laugh. But towards the end of the band, when we weren’t doing the music, we weren’t able to be comfortable with each other anymore.”

While the drink flowed freely in the studio, Marr expressed his desire to try out new ideas and explode the crumbling myth of the Smiths as a jingle-jangle guitar group cosy with their reputation as indie kings. In one respect, this seemed a healthy attitude but also testified to the group’s underlying problems. Marr was clearly restless and, although there was enough interesting music on the new album to satisfy his current needs, he resembled a man in search of fresh challenges.

Stephen Street remembers one moment during the recordings when the immemorial camaraderie between Morrissey and Marr almost turned nasty. “It was when we recorded ‘I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish’ that it happened. Johnny and I had been working on a guitar line all afternoon and got something that we felt had a strong glam rock feel like T. Rex. Morrissey came over to listen to it and said, ‘I don’t like it.’ Johnny wasn’t in the room, so I had to go back over to him in the cottage. I said to him, ‘Morrissey doesn’t like it.’ Johnny said, ‘Well, let Morrissey fuckin’ think of something.’ I thought, ‘Hold on a minute! This is the first time!’ Normally, Johnny would have said, ‘OK, I’ll have a chat with him and sort it out.’ Johnny was fed-up being relied upon to come up with something all the time and no one actually telling him what they wanted. Morrissey would just say ‘yes’ or ‘no’. He couldn’t say, ‘I’d like to do this’ because he doesn’t have a musical background.”

Although the session was generally a happy one, Street detected an “underlying tension” in Morrissey and Marr’s interaction. “It was strained, I think, because of Ken Friedman. Johnny trusted Ken and was fed up with taking on lots of responsibilities, administration and general management of the band. I think he wanted somebody to look after that and organize a proper tour. Morrissey wasn’t sure that he wanted Ken to do that. Ken was actually staying in the studio as well, sleeping on the couch. You could tell Morrissey didn’t want him around.”

Morrissey had always resented outside influences on Marr, the more so if they affected the duo’s creative partnership or close personal friendship. “I didn’t like Johnny bringing strangers into the studio,” he admitted. “He allowed anybody in, he was very free with people which I didn’t agree with. I wished to preserve our intimacy… The fact that I rejected his friends implied that I was boring and hated the human race.”

Stephen Street had to be alert throughout the sessions, dealing with Morrissey during the mornings and accommodating Marr’s late nights. “He didn’t get up till 4.30 pm,” he recalls. Often, Street would work the long evening shift with Marr, at the tail end of which Morrissey would re-emerge to offer an opinion. “They’d just had this very stressful US tour and there was a bit of stress there which carried on right up to doing this album. I definitely got the impression that they hadn’t prepared as much for Strangeways as they did for the other albums. There were a couple of half-baked ideas. The rest of the album, when Morrissey was putting his vocals down, that was the first time Johnny had heard that line. That had happened before on a couple of other tracks on the previous album, but here it was quite obvious as Morrissey was saying, ‘OK, do that beat, and a few bars there.’”

On one of the new songs, ‘Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me’, Street recalls helping to “arrange some of the string lines” and playing along with Marr “on the keyboard parts”. After completing this productive session, Street was bold enough to confront Marr with a provocative request: “Do you think if you’re doing string credits for this album, you could say, ‘Marr/Street’?” It did not go down well. “He looked at me and said, ‘I don’t know about that!’ I thought, ‘OK – stop!’ I realized I was overstepping the mark, so I never brought up the subject again. I thought I’d put some input on the string arrangements so… fair’s fair.” Street was quick to add his admiration for Marr. “I wouldn’t want people to think I was trying to take a piece of the credit away from Johnny. When you work for someone like that – it’s inspiring… You knew that if you could just get him comfortable and at ease then you could just let the tape roll and he’d come up with stuff.”

Morrissey also encountered various problems while recording the album. “Half-way through he decided that he had to go back to Manchester because he couldn’t deal with the pressure” Street says. “That was also due to the fact that he had to write some lyrics. We recorded some backing tracks and he hadn’t prepared lyrics for them. So, he had to disappear and we had to wait about four days.”

Appropriately, the LP borrowed some of its inspiration and mood from The Beatles during their final phase. The hidden soundtrack to the album was The Beatles and Let It Be. Marr had been listening to the annoyingly mistitled ‘White Album’, that strangely eclectic work in which the Lennon/McCartney writing credit could no longer disguise a resigned artistic neutrality. In recording the new album, he desired some of the taut, longing for discovery that characterized The Beatles’ latter work. Marr’s view of The Smiths’ concluding LP betrayed a hint of wonderment. “It was dark, stark, organic and held together by atmosphere with very few overdubs. There was poignancy there. It might have been my imagination but, having seen the documentary Let It Be, I think there’s an air of foreboding that’s definitely there on some tracks. There’s a lot of depth to that LP which came about because of our feelings at the time.” Although Marr claims he had no reason to assume that this would be The Smiths’ swansong, he could hardly have chosen a more suitable or inspiring valedictory than Let It Be.

While The Smiths were completing their new studio LP, Rough Trade released two compilation albums within the space of a couple of months. The World Won’t Listen was the sequel to Hatful Of Hollow, and a welcome collection of the group’s recent hit singles and flip-sides. The bargain priced set included the unreleased ‘You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet, Baby’, a title allegedly inspired by an innocent one-liner from Geoff Travis. In addition to the more familiar tracks was an edited ‘That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore’, the original Drone Studios version of ‘The Boy With The Thorn In His Side’, minus the synth strings, and an alternate take of ‘Stretch Out And Wait’ with the opening lines mysteriously altered from “Off the high rise estates…” to “All the lies that you make up…” The subsequent Louder Than Bombs was a more expansive and expensive collection, featuring 24 songs from every stage of the group’s career. Although originally intended for American distribution only, Rough Trade elected to issue the set when highly priced import copies threatened to invade the home market.

The third Smiths release of the early spring was the single ‘Sheila Take A Bow’, which equalled their highest chart placing at number 10. The song had been written very quickly and, during the initial session with John Porter, Morrissey had recorded his declamatory vocal in one take. He seemed so impressed with the results that he refused the chance of a repeat performance. Thereafter, he had a change of heart and a second version would be cut with Stephen Street. What emerged from the confusion was a splendid glam rock pastiche with a thumping arrangement that sounded like a cross between Gary Glitter and a Salvation Army Band, complete with bombastic oompah drumming. Melodically, there were echoes of David Bowie’s ‘Kooks’, itself inspired by Neil Young’s ‘Cripple Creek Ferry’, Maintaining the Bowie link, Morrissey paraphrased a key line from ‘Kooks’ (“if the homework brings you down, then we’ll throw it on the fire”). With its mild plea for adolescent rebellion, the lyrics offered a temporary sanctuary from the headmaster ritual. The song also championed the sexual confusion of early Seventies’ pop with an arch example of gender confusion (“You’re a girl and I’m a boy . . . I’m a girl and you’re a boy”) to add spice to the proceedings.

The flip-side, ‘Is It Really So Strange?’, employed another of Morrissey’s favourite allusions – the trip down south. Rather than the urban drama of ‘William, It Was Really Nothing’ or ‘London’, Morrissey creates a love song of comic confusion. There is even a wilfully playful reference to, of all things, animal slaughter, with the killing of a horse. Accompanying the frantic travelogue is an almost absurdist landscape in which aggression and fun intermingle incongruously. It is akin to entering the mindset of a psychotic narrator whose moral compass is not so much askew as non-existent. Characteristically violent imagery is used as an expression of commitment, with words such as ‘kick’, ‘butt’ and ‘break my face’ preceding a carefree romantic declaration of love. The psychotic sensibility recalls ‘The Queen Is Dead’ wherein regicide and comedy combine wonderfully well. In that song the Queen’s fate seemed contextually of little more importance than the rain that flattened the singer’s hair. Here, the slaying of a nun is similarly undercut by what may well be Morrissey’s greatest moment of bathos: “I lost my bag in Newport Pagnell”.

The 12-inch version of the single featured the bonus ‘Sweet And Tender Hooligan’, a strident rocker with some engagingly sardonic lyrics concerning the treatment of violent offenders by liberal juries. The sarcasm is so biting that you are almost left with the impression that the singer is siding with the psychotic ‘hooligan’. Given the narrative of the preceding ‘Is It Really So Strange?’ that was hardly surprising. Both the B-side tracks had been recorded and broadcast the previous December on the John Peel Show. However, producer John Porter found little cheer in their release, which coincided with his final ostracism from The Smiths’ camp.

According to Stephen Street, the group were supposed to re-assemble at the Wool Hall, Bath, approximately three weeks after finishing the album. The purpose of these sessions was to complete some B-side tracks for the singles that they would pluck from the LP later in the year. At the appointed time, Rourke, Joyce and Street appeared, but there was no sign of Morrissey or Marr. Eventually, a call was received from the guitarist, asking “Is Morrissey there?” The answer was “No!”

Street concludes: “I think he got wind that Morrissey had suddenly decided not come down to the studio. Johnny said, ‘I’m off then!’ The session was cancelled, and I believe he went to do those Talking Heads overdubs in Paris with Steve Lillywhite. That was the last time I spoke to Johnny for quite a while. I didn’t think anything about it. I just thought they’d had an argument.”

What complicated matters was the presence of Porter and his wife Linda, who accompanied Johnny and Angie on the trip to Paris. During the visit, the party received an uncharacteristically effusive telephone call from Morrissey, which puzzled Marr. On the way home, Porter, whose communication with the singer was by now virtually non-existent, felt convinced that something was amiss. It was not until after the release of ‘Sheila Take A Bow’ that he discovered the worst.

As was often the case in his working relationship with Marr, Porter was liberally allowed to add a slide guitar or puzzle over a chord sequence while awaiting his young friend’s arrival in the studio. It was all part of his work as a producer. But, to put it mildly, there seemed to be a communication breakdown following his work on ‘Sheila Takes A Bow’. The producer still recalls his abject disbelief upon hearing what sounded like an alternate take of the single on the radio. “The first thing I knew it was out and it sounded slightly different,” he told me. “When I saw the record it said ‘produced by Stephen Street’. Morrissey had gone in with Stephen Street, done the track again, but sampled guitars off the original and put them on this new one without mentioning it to me, asking me, giving me a credit, paying me, or doing anything. That was the last I ever had to do with The Smiths. I never said anything to anybody, but I thought, ‘If that’s what it’s down to. You didn’t even ask me!’ In theory, I could have stopped the record and done a whole number. So that was the end of it. The original version of ‘Sheila Take A Bow’ was just as good as the one they put out. It was just Morrissey trying to prove a point – that they didn’t need me.”

John Porter’s indignation was understandable, but what is interesting is the way Marr was not named in this narrative. Porter gives the impression that Morrissey unilaterally elected to re-record ‘Sheila Takes A Bow’ and, reading the above, it sounds as if he secretly took a tape of the original backing track and superimposed a new vocal, assisted by Stephen Street. Of course, the song was completely re-recorded by all four Smiths and it was not Morrissey who was responsible for sampling a guitar part from the original. As Stephen Street later told me: “We were running a bit short of time and there was a guitar line that Johnny had on the last session with John and he couldn’t quite remember who it was that did it… I think it was a slide bit… At the time I didn’t think much about it… I thought it was just a piece of work that Johnny had done and couldn’t be bothered to re-create. It was a guitar line and sounded good, so why bother doing it again?”

This unhappy accident should and could have been avoided, but evidently nobody from The Smiths’ camp informed Porter of the proposed re-recording, not even Marr. As a matter of courtesy, that was the least he deserved. Despite his hurt, Porter never voiced any criticisms of Marr in this scenario, but directed his anger firmly against Morrissey. Although the singer clearly had a preference for Stephen Street as the group’s producer, Porter still believes that it was his developing friendship with Marr that proved his undoing. “I think going to Paris with Johnny was the end for Morrissey. When I first worked with The Smiths, Morrissey was very appreciative, but subsequent to that he got jealous of my relationship with Johnny. We were good mates and used to hang out and party together. Morrissey, having always had Johnny as his close musical partner, began to resent my old fart influence and just my friendship with Johnny.” For his part, Marr felt that the personal and professional relationship he had with Morrissey was invaluable and so he tried to steer clear of emotional conflict. Nevertheless, the departure of various associates was sometimes regretted. “Everybody was just axed away from it,” he told me, “and it was a bit difficult for me.”

One of the enduring mysteries of the Morrissey/Marr relationship is the way the guitarist acceded to such decisions. Marr was a strong personality in his own right and certainly no wallflower. Why did he not fight harder or stand up to Morrissey if he believed something was wrong? Obviously, theirs was a complex dynamic but, in both financial and business matters, a ‘Morrissey decision’ was, by definition, also a Morrissey/Marr determination. The status of Rourke and Joyce, the fate of Joe Moss and John Porter, and much else, may have emanated from Morrissey but, rightly or wrongly, Marr went along with his partner. That said, the various so-called ‘axings’ may not have been entirely down to Morrissey and his whims. There was also ‘natural wastage’. Some people simply disappeared from The Smiths’ narrative in the same way that casual friends lose contact for no specific reason beyond changing circumstances. When any act achieves a certain degree of popularity, former friends or associates inevitably get left behind. It even happened to some people in Marr’s circle, including Ollie May and Pete Hope. “Pete used to work in a record shop and Johnny would get imports at good prices,” Joyce recalls. “Then The Smiths became quite big and Pete phoned up, and Johnny just ignored him. It happened on numerous occasions.” Given the constant changes of phone numbers along the way, maintaining contact with former associates was never likely to be easy. All too often there were bigger issues to consider.

After finishing work on the new LP, Marr went through a period of torturous reassessment over the future of The Smiths. The album had allowed him to explore some new ideas, but he still felt restricted musically, politically and personally. The Smiths had become like a club in which certain influences were deemed sound and others regarded as taboo. The fact that Marr was presently enjoying such old favourites as Sly And The Family Stone and The Fatback Band, as well as finding empathy with the latest developments in dance music, made him feel more divorced than ever from The Smiths’ central fan base. At one time, Morrissey and Marr had seemed uncannily united in their musical opinions, but the guitarist was now growing weary of the old kitsch icons associated with his partner. As he later told Manchester DJ Dave Haslam: “Towards the end of the Smiths, I realized that the records I was listening to with my friends were more exciting than the records I was listening to with the group. Sometimes it came down to Sly Stone versus Herman’s Hermits. And I knew which side I was on.” Always hip to Manchester’s musical undercurrents, Marr fully understood that dance music was on the rise and sooner or later he would be forced into a musical cul de sac under the reductive Smiths’ banner. Even before recording the LP, he had betrayed reservations about The Smiths being typecast as a ‘jingle jangle’ group. Although the recent sessions had proven productive and indicated the possibility of a new direction, Marr felt boxed-in and overworked. Suddenly, The Smiths seemed like a tiring treadmill. He told his fellow players as much, suggesting that they were all in danger of allying themselves to a musical dinosaur. “We’re going to end up like The Beach Boys in the blue and white striped shirts,” Marr warned Morrissey in frustration. Marr sensed that rival competitors would eclipse the Smiths if they failed to change their ways… but in what way they should change remained uncertain.

With various legal and business problems on the horizon, disputed management interests, a forthcoming television documentary and a hungry EMI eagerly anticipating new product, Marr above all desired a long break. One evening, he confronted Morrissey in Chelsea and poured out his feelings. Before long, the subject of a complete break-up was broached. “If we went to a lawyer and dissolved our partnership I would see a great weight lifted off your shoulders, which would also be a weight lifted off mine,” Marr informed his partner. “That was the way I wanted it to go,” the guitarist told me. “It wasn’t purely me, me, me. It really wasn’t. I felt if the group were to split I’d see some massive physical improvement. The pressure was far too much. I wasn’t fed up with the guys, it wasn’t that at all. I just felt all of us were in an unhealthy situation and unless we made some moves towards thinking about our future direction, we’d become an anachronism.”

Later that evening, Marr confronted Joyce at Geales Fish Restaurant in Farmer Street, Kensington, and repeated his comments. Joyce’s response was incredulous. “What do you mean you don’t want to go on anymore?” he demanded. In light of the recent album sessions, not to mention the EMI signing, the drummer found Marr’s attitude perplexing. “If we’d recorded another album and things had slowly ground to a halt it would have been easier to come to terms with,” he says. Looking back for motives that would explain Marr’s disenchantment, Joyce could only find hints of strain and overwork. “Maybe I wasn’t sympathetic enough to the way Johnny was feeling. He would express his dissatisfaction and anger about something more so than Morrissey. But I don’t think he did on this occasion and, because nobody saw the signs, he got a bit upset. He wanted everyone to rally around him and say, ‘Don’t worry, have some time.’ It was all a massive shock and I just remember it being surreal.” Joyce did not take Marr’s mood lightly. “I thought he really meant it. That’s why I wanted to sort it out there and then. I thought, ‘If we leave this, then that’s it, really.’ ” In the circumstances, Joyce innocently uttered the kind of sentiments that Marr least wanted to hear. “I think we should do one more album,” he suggested.

The remaining Smiths could hardly believe what they heard or face the truth. It wasn’t as if Marr had articulated precisely why he wanted to end The Smiths, especially when they still seemed at a creative peak. His reasons were myriad: part musical, but also personal. As Rourke concludes: “Obviously, something had gone on with Johnny and Morrissey which we didn’t know about. It came as a big shock to us… Johnny made it plain that he’d had enough. It had sort of taken over his life, and he wanted out basically. The demands of Morrissey he couldn’t really handle any more. Like pandering to his whims. He got sick of all that after a while.”

Morrissey felt equally deflated by Marr’s attitude, especially with the EMI era looming. The Smiths seemed on the brink of even greater achievements and financial security and here was Marr threatening to throw it all aside. Despite the intensity of the conversation at Chelsea, Morrissey misread the signs and put Marr’s disenchantment down to tiredness and overwork. That same week, the group were filmed for a prestigious documentary, The South Bank Show special, and talk of a possible split was suspended. Marr then announced that he intended to take a vacation and advised everybody else to do the same. The reaction was negative and suspicious. “It was the ultimate sin to suggest that,” Marr told me. “The band made me feel that I was never going to come back, which wasn’t the way I felt. Morrissey was acting so defensively. That annoyed me. They should have given me some time to sort it out and see a way forward.”

Marr continued his protest until Morrissey relented somewhat and suggested: “Maybe we should all take a holiday together.” At that moment, Marr threw up his hands in exasperation and said, “No! You’re missing the point.”

What The Smiths urgently needed at this stage was a mediator. Instead, they ended up in opposing corners. Friedman was by now a distant presence, who was completely estranged from Morrissey and very sad about the conflicting attitudes that were tearing the group apart. Having returned to America, he took stock and planned a therapeutic holiday touring Thailand and Nepal. After all the recent Smiths problems, it would prove a welcome break. Morrissey, meanwhile, increasingly turned towards Geoff Travis for business advice and was now disputing the commission that Friedman had claimed for his managerial services. Marr stayed loyal to the American, mainly because the alternative seemed a return to chaos. “Morrissey had decided that he didn’t want to work with Ken, which was OK,” Marr explains. “That was a problem I could have dealt with. I just felt round the corner it was never ending.”

Viewing events from the sidelines, Grant Showbiz lamented the absence of a single, authoritative voice. “If there’d been better management, things would never have reached the crisis point. It was too intense towards the end. I felt it was like a furnace. Ken was manager. Writs were flying back and forth. Craig wanted his money for playing on the tour and there was a lot of emotional pulling going on. If they’d just had one person who could have said, ‘I’ll deal with it.’ It was like The Beatles at the end.”

Friedman, who had long been consigned to Johnny Marr’s corner, noted the developing schism from a distance, with a degree of frustrated regret. “Everybody chose sides with The Smiths,” he emphasizes, “that’s just what happened. Morrissey’s mother was on Morrissey’s side, Johnny’s wife was on Johnny’s side, Geoff Travis was on Morrissey’s side. It just got to the point where it was high school”

Marr’s attempt to play truant from The Smiths was again forestalled when Morrissey insisted that they complete a couple of B-sides for their next single, ‘Girlfriend In A Coma’. “I fought against it,” Marr told me. ”I felt I’d worked far too hard to be put in that position. I just felt it was complete insanity while we were under all this pressure.” Despite Marr’s objections, the sessions were scheduled to take place during May at the home studio run by Grant Showbiz and Fred Hood.

After the group arrived for the Streatham sessions, Grant rapidly realized that all was not well. “The divergence came at the time we were doing those last tracks,” he recalls. “It was a very odd atmosphere all round. I’d never felt that with The Smiths and didn’t really know what was going on. Johnny and Morrissey weren’t really talking to each other, which was weird. I’d say it was a communication breakdown caused by uncontrollable outside pressures reaching a peak. They were looking to each other for a solution that neither had.”

From the moment he entered the studio, Joyce realized that this latest get-together was a mistake. “It was total madness”, he says. “Everybody was losing it. I was a bit flippant about it, really… A lot of things happened subconsciously and you couldn’t put your finger on it. I just didn’t feel my heart was in it. It was a strange atmosphere. I didn’t feel there was any need for us to be there. I hadn’t objected to Johnny taking a holiday at all. Why should I? If he’d said six months, it wouldn’t have bothered me. I’d have gone off and done my own thing. Streatham was probably the last straw for him. Johnny was feeling the pressure from within.”

Marr’s memories of the Streatham sojourn were decidedly depressive. “It was utter misery. The group were really falling to pieces.” His grudging reluctance to even be there added a frisson that Grant Showbiz had never previously witnessed at any gig or recording session. “Having seen the harmony, I noticed this lack of communication. It wasn’t as if the songs were properly formed. Morrissey was saying, ‘Let’s go and do the song!’ and Johnny would say, ‘What song, Morrissey?’ He’d reply, ‘Well that thing you were playing earlier on, I’ve got some words.’ It was very weird. They had ideas for songs with different names. One was called ‘You Don’t Know Anything’. They were just sketches.”

Morrissey seemed rather nervy throughout the fractious recordings, as if he realized that the entire future of The Smiths was inexplicably crumbling away. “There weren’t a series of rows leading up to a break-up,” Grant stresses, “just a sudden realization. It was lots of little things and hitting the bottom of a cycle and not having anybody to rationalize it and say, ‘You’re all knackered, go away and don’t think about The Smiths.’ Morrissey, for once, was desperate to do something and no one else was. The fact that he was willing to carry on suggested that at that time he wasn’t thinking too rationally and was getting really obsessed with The Smiths. Morrissey was very unhappy in that period.”

Perhaps as a subconscious attempt to rekindle the old camaraderie, Morrissey looked to the early/mid-Sixties for affectionate inspiration. At one point, he took Joyce aside and began raving about an obscure Sixties single that apparently contained some brilliant percussion. “He said, ‘Check out the drumming!’ It was insane – a quintessentially English, big band orchestral arrangement. That was what he was into.” Joyce’s lack of appreciation for such a piece was not too surprising, but Morrissey expected a more enthusiastic response from his songwriting partner. The Morrissey/Marr duo had first found common ground in their love of girl groups and Johnny had always displayed a tolerant enthusiasm towards his partner’s love of Sixties kitsch. At Streatham, however, even that creative link was fraying.

Morrissey’s whimsical idea of covering a Cilla Black B-side and film theme merely embarrassed Marr. “I hated ‘Work Is A Four Letter Word’,” the guitarist grimaces. “I didn’t form a group to perform Cilla Black songs.” When I reminded Marr that he had sanctioned a Twinkle cover eight months before, he swiftly added ‘Golden Lights’ to his black list. “That was another low point,” he stresses. “Those are the two low points of our recording career, certainly, and don’t deserve a place alongside our material.”

Joyce agreed with Marr’s criticisms of the Streatham songs: “I didn’t feel the vibe was there and Morrissey wasn’t singing that well. He did a vocal and said, ‘That’s it!’ I thought, ‘Well, OK, if that’s what you think.’ Everybody seemed a bit flippant.”

By 19 May, work was completed on the final Smiths recording ‘I Keep Mine Hidden’. Morrissey whistled breezily through the track, sounding not unlike a modern-day George Formby. The song was to remain his favourite over the next few years and represented a treasured postscript to a partnership that had run its course. Three days later, the singer celebrated his 28th birthday. It was not a notably happy occasion. Morrissey wasn’t to know that his unhappy birthday was effectively The Smiths’ wake. As legal documents later confirmed, the Morrissey/Marr partnership effectively ended on 31 May 1987.

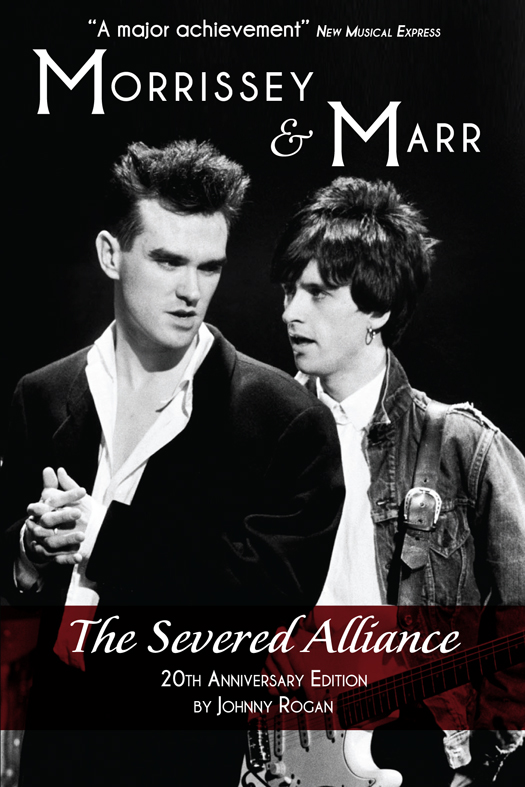

The Severed Alliance is available from Omnibus Press