As truisms go, it’s not exactly true that nothing happens in a vacuum. The entire history of the known universe, from year zero to the present day, for example, has played out in within the infinite confines of the vacuum of space. What is closer to the truth, though nowhere near as catchy, is that socially, culturally – and probably ecologically – nothing happens in a vacuum.

An artist of more or less any kind can absolutely claim that their work is a-political in terms of intention – but that piece of work, whatever it might be, was created under the influence of layers upon layers of social discourse that its creator either consciously understood or was, at the very least, aware of by a kind of idea osmosis.

Now, I’m not saying Roland Barthes can go fuck himself – Roland Barthes is dead and 25 years of decomposition probably means he lacks the basic equipment required to attempt the beautiful act of self-love – but, while the Death of the Author is one thing, complete separation from context is another entirely. (Side note: imagine Roland Barthes’ fetid, remnant junk hooking up with Jeremy Bentham’s perfectly preserved head. You’re welcome.)

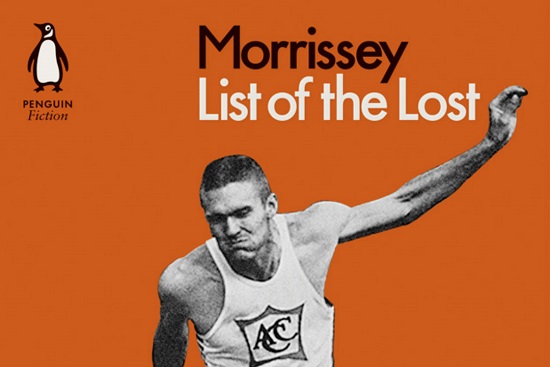

I bring this up, whatever it is, because reading Morrissey’s List of the Lost is different to reading Morrissey’s Autobiography: whatever else it is or isn’t, List of the Lost is a novel. List of the Lost is fiction. Does it – or, rather, should it – matter, then, that List of the Lost is the most Morrissey thing that Morrissey has ever done; that it’s the apotheosis of Morrissey; peak Morrissey; the caesarean birth of Morrissey (and his bulbous salutation) as meme?

The answer, of course, as it is with all “yes or no” questions, is yes and no. While it is impossible to divorce Morrissey’s written, fictional prose from the many (many) other self-indulgent, ill-advised diatribes spawned from the tips of those fingers over the years, it’s still as wrong to perceive the narrator of List of the Lost as the voice of the man himself as it is to assume Patrick Bateman is necessarily a refraction of Bret Easton Ellis.

With that in mind, and with Moz the man subsequently out of mind, how would List of the Lost hold up under scrutiny if it were the work of a first-time writer, of a non-entity?

Fundamentally, List of the Lost is a book about a sporting team and features several references to sports; it also features a complete disregard for any ability to write convincingly about sports. From the half-mile relay team at the heart of the novel (there are no half-mile relay teams) to a description of Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali’s fractious bout as a “glorified shoving match”, the level of disdain for the subject matter is not only unusual but also a recurring theme. Whether it’s language, sex or more-or-less any human interaction, it’s clear – and it’s just about the only thing that is clear – the author has at best no truck with them and, at worst, no comprehension what so ever.

Not liking, or knowing, your subject is one thing but there is absolutely something to be said for the drawing out of a sentence – for minutiae, for borderline excruciation – and for the idea of boredom as device. José Saramago’s All The Names, David Foster Wallace’s not-quite-realised The Pale King (and, of course, Infinite Jest) as well as much of the alt-lit canon stand as clear examples of that fact, and Knausgård’s My Struggle straddles the line with less authority.

It’s possible, then, to consider the sluggish, overwrought quality of List of the Lost’s prose as a tool: so, where Morrissey writes “Look at them now in their manful splendor and wonder how is it that they could possibly part this earth in dirt, as creased corpses, falling back as the skeletons that we already are, yet hidden behind musculature that will fall in time at life’s finishing line,” it’s not impossible that what we’re looking at here is a kind of supreme allegory. As the bodies of Ezra, Hari, Nails and Justy decay, over an extended period of time, from “manful splendor” to “creased corpse,” so the text degrades from the litheness of its first few words in to a bloated, wretched cadaver.

Yes, that could definitely be a thing; that could easily be what’s going on here. But, also, it definitely isn’t. The clunky, near-archaic quality of both the vocabulary and the syntax doesn’t even come close to hinting at a Bigger Idea, so much as it points to someone who read a few shitty Dickens novels at school and, having not touched a contemporary novel since, presumes that writing in 2015 is just the act of applying that same framework to a present-day narrative. (Case in point: “Amongst the dead wood and the dead nettle, the cave-dweller was out of play; a lumpenprole dead weight within less than an instant, seventy-five years to reach such jell-brained release … but to where, to where?” You fucking what, mate?)

That’s not how it works, though, is it? And what you’re actually looking at is some of the most heinously overblown prose printed by a major publishing house in living memory. It isn’t Joycean cacophony; it isn’t morbidly exhibiting a Dante-esque ability to capture Man’s descent into madness, into hell, through language. (Although, to the author’s dubious credit, reading it does have a similar effect.) It’s neither enjoyable to read nor purposefully unpleasant; or, loosely translated, it’s "not good".

And speaking of hell, it seems inevitable in discussing List of the Lost – given how quickly that coinage, yes you know the one, has taken root, bloomed, and rotted in the collective mouth of the English language – that we come to Morrissey’s take on the erotic.

To be clear from the off: sex isn’t easy. In literature, as in life, some people get it and some people don’t, and being bad at writing sex isn’t the same as being bad at writing in the same way that being bad at having – or getting – sex isn’t the same as being bad at life in general. As recently pointed out to me by a friend, Haruki Murakami’s propensity for having his male characters come “over and over” without ever once, so far as we could recall, straying into the apparently-forbidden territory of the female orgasm is a certain kind of bullshit (though whether it’s bad writing, wish fulfilment or patriarchal egocentrism I’m still not sure). And I distinctly recall a year of the Bad Sex Awards in which Stephen King suggested that a woman’s breasts were spherical.

Now, those are two of the 20th-century’s most popular novelists — if they can’t write about people getting down to it with the same tension, beauty and air of the grotesque that May-Lan Tan does in Things To Make And Break, how can we honestly expect Morrissey to deliver on that front? The upshot is that we just can’t. But not holding someone to the highest possible standards of writing about sex isn’t the same as giving them a free pass. If you’re reading this (it’s too late) you’ve probably already given some thought to what follows, regardless, take a moment to consider this paragraph:

“Eliza and Ezra rolled together into the one giggling snowball of full-figured copulation, screaming and shouting as they playfully bit and pulled at each other in a dangerous and clamorous rollercoaster coil of sexually violent rotation with Eliza’s breasts barrel-rolled across Ezra’s howling mouth and the pained frenzy of his bulbous salutation extenuating his excitement as it smacked its way into every muscle of Eliza’s body except for the otherwise central zone.”

As adjectives for intercourse go, “dangerous,” “rollercoaster,” “coil,” and “violent” are about as subtle as shitting in a bag and presenting it, with a wry smile, to someone you don’t like. (They also, as Michael Hann rightly points out, exhibit some fairly alarming hang-ups about sex.) Rollercoaser, in particular, is something special: oh the ups, the downs, the rush – the adrenaline! – the disappointing brevity.

Separating the wheat from the chaff, though – sitting nonchalantly alongside arduously trite metaphors – there are some Properly Fucking Perplexing lexical choices here. Barrel-rolling breasts, bulbous salutations and otherwise central zones have achieved the kind of notoriety most coinages take years to amass, and they’ve done it without actually meaning anything. And, considering Morrissey describes himself as “humasexual”, it’s strange to come away from List of the Lost with the distinct impression that the author of this book has never seen, let alone participated in, any configuration of human-on-human sex. In fact, the whole passage could just as easily be read as a description of two people playing on the stairs with a slinky.

So, what does all this actually mean for List of the Lost? Well, fore mostly, it means that I’ll never visit a zoo again because I don’t think I’ll ever see a penguin without wanting to punch it in the face.