Everything was preceded by months of preparation, but in the heat of things, the signal was given by someone other than planned. About a 100 young people age 15 to 30 ran onto the Velká Pardubická steeplechase track to interrupt the legendary race. They held on to one another in a human chain link until the police started to spray tear gas in their eyes and beat them with batons, all the while being applauded by race spectators from the grandstand. What followed were chases, arrests, and more beatings. "Anarchists got what they asked for", said newspaper headlines, but the goal was accomplished: attention was brought to the most dangerous steeplechase in Europe. The following year, only one horse finished the race, a large sponsor left, and subsequently the track was modified to lessen the danger for animals.

It was also a very significant change for those who ran onto the racetrack on that day in 1992. It was the first time since November 1989 that police beat young people so brutally: students, ecologist, sociologists, anarchists, and a significant part of the then-emerging hardcore-punk scene. It was this particular group that felt the experience as a bitter awakening after the Velvet Revolution, which had been based on dialogue, understanding, and peacefulness (that´s what the “Velvet” part meant).

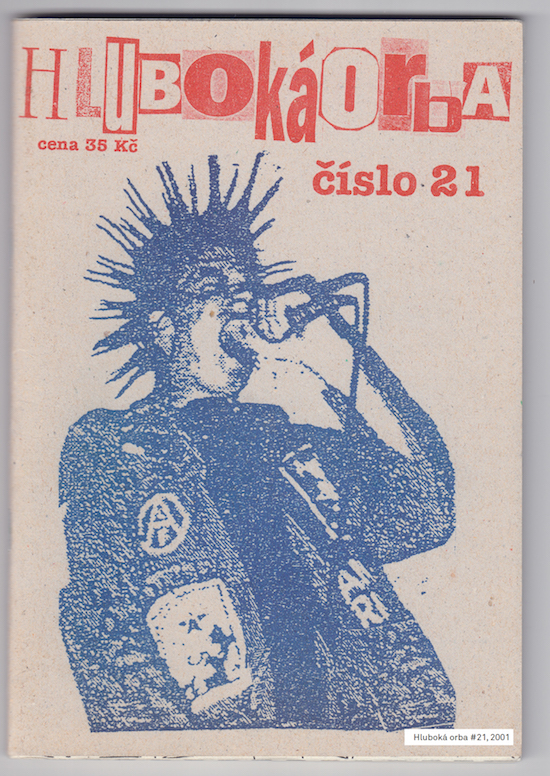

The experience from Velká Pardubická also lit a spark in then seventeen-year-old Filip Fuchs. It was here that he realised that determination and diligence can change the course of things. From then on, such determination was present in everything he did. Be it from activism to playing in a band, working as a Roma community lawyer, to publishing a hardcore-punk fanzine called Hluboká orba (Deep tillage). For the next 23 years, as the longest-running Czech fanzine publisher, Fuchs tried to convey the same enthusiasm to his readers. To some, he was a punk fan, to others, a radical fanatic. Either way, he was the embodiment of the saying that hardcore is more than just music; there probably isn’t a better example in the history of Czech fanzine culture of someone for whom making fanzines was first and foremost an obsession.

Defining borders

Czechoslovak fans who wanted to listen to fast guitar music in the Eighties could do so relatively easily through fairly accessible international heavy metal albums. Curiosity for something even more radical lead many, through an indirect route, to discover hardcore punk, a genre which originated at the beginning of the decade in the United States as the music of outsiders with clear-cut opinions.

In the Eighties, the favourite black market records were the rare ones of the Sex Pistols, which gave Czechoslovak bands a sartorial style and three-chord music to imitate. Getting to hardcore music was harder and meant more. It meant knowing the right vinyl bazaars and collectors, of whom, according to contemporaries, there were no more than 10 in total. These enthusiasts would, with a bit of luck and help from friends travelling to East Berlin, have access to records of bands like Black Flag or Minor Threat, bands whose style was more furious than that of anyone ever before.

Hardcore fervour was breath taking. Its music was primal, its lyrics gave comfort to losers both voluntarily and involuntarily ostracised from society. For rebellious teenagers in whom the realities of socialism amplified the urge to resist, hardcore was a direct hit. They mostly didn’t understand the English lyrics; songs were translated by self-taught enthusiasts and by writers of samizdat (self-published) newspapers such as Vokno or the Brno fanzine Šot, and others. Here, fans read that not only is it important how bands play, but also what they think.

"It was an inner necessity of resistance, a way to not go prematurely insane", Šot writer/publisher Luboš Vlach recalls of his motives for writing about hardcore bands and publishing under threat of interrogations or imprisonment. Fanzines were replicated in "Commie factories on capitalist copy machines", as another underground publisher recalls. The best place to print fanzines was secretly at work or in select printing shops that were known to not ask for an ID card.

Much got lost in translation, but perhaps it was because of this that domestic bands set in Normalisation-era Czechoslovakia had a specific style. While foreign bands created independent distribution networks and defined themselves against the American Dream, consumerism, and rock star manners, local bands in the mid-Eighties (Zelení kanibalové/Green Cannibals, Kritická situace/Critical Situation) criticised oppression, warmongering, and compulsory military service. "We’re eternal, eternal deserters. On the run from start to end, we can’t even stop", sang Kritická situace before November 1989.

The essence isn’t determined by the centre

In November 1989, the Velvet Revolution came. Lists of collaborators of the regime began to appear and archives were opened. Barbed wire border fences were taken down and the country experienced an influx of Western information, goods, and money. The planned economy was replaced by the invisible market hand and by “divoký” aka wild capitalism (also known as cowboy capitalism). Queues for bananas and toilet paper were replaced by a chase for deep fryers; the first swindle sellers began to appear, and coupon privatisation was taking shape: the transfer of state-owned property into the hands of people through a coupon system. For someone who desired to be in opposition, it wasn’t difficult to demarcate against this and to refuse to accept the contemporary canon.

In 1990, Luboš Vlach published a sort of domestic hardcore program in the thirteenth issue of Šot. In it he wrote the following: all orthodox h/c bands belong on the fringe. The essence isn’t created by the mainstream, but by the periphery. Hardcore isn’t only interested in consumer culture. Hardcore is daily life, a life-attitude, an autonomous reaction to the world. "Damn it, what more would you need to hear at 15 in order to pick up a guitar and start bashing it?" wrote Filip Fuchs many years later about how the fanzine affected him in 1990.

It was the first time he ever held such a magazine in his hands. He read about anarchism, vegetarianism, animal rights, the need to fight racism and about radical punk, which stood in opposition to commercial bands. "I was captivated by the raw, black-and-white, Xeroxed look— just a typewriter, scissors, glue. The fanzine was as black-and-white as my outlook on punk and on the world back then", he recalls.

It was also in those times that news began to appear in the Czech press of local racist skinheads performing armed attacks on Roma and Vietnamese ethnic groups as well as anarchists and skateboarders. Punks, as fans of radical music styles were called, found enemies—and they were the first to organise demonstrations against racism. Some pre-revolution punk bands also signed on to major record labels. At this moment, an independent hardcore-punk scene began to take shape. Before, everyone stood together against an oppressive government regime; now was the time to define borders. This was aided by one particular manifesto.

"Now let me explain what the album title means to those less sharp. It goes along the lines of: Mammoth labels, fuck off! Our dream is to awaken bands and show them: It can be done! Make records on your own! Don’t feed the fat cats! If you’re stuck, write to us. We’ll help!" This was the messageon the cover of the compilation Fuck Off Major Labels, released shortly after the revolution by Brno punk and music fanatic Martin Valise through his label Malárie Records.

Valášek organised concerts in Brno in the Eighties, which is where he met dissidents and discovered samizdat publications. During childhood, he would copy Polish music charts into his textbooks and, nearing adulthood, he started to contribute to pre-revolution samizdat magazines and to publish his own fanzine Malárie (Malaria). He was constantly on the road with bands and was present whenever anything of importance happened. He wouldget the addresses of foreign bands from the back cover of their records, interview them by post, then publish the interviews in Malárie. In the zine he would help translate and adapt the ethics of hardcore—a strict ethical code of DIY principles—for the Czech scene.

The code was based on the idea that only a minimum of resources is necessary, that there shouldn’t a barrier between a band and the audience, and that expensive studios, sponsors, and managers are unnecessary. The potential of free trade and the idea of turning his fanzine into a professional magazine didn’t appeal to Valášek. On the contrary, such technical perfection wouldn’t match the attitudes and ideas emanating from a badly printed magazine or from a noisy recording. This community of a few hundred unyielding believers made camp firmly on the periphery and vehemently defended it.

Turn your brain on – turn the TV off

When seventeen-year-old Filip Fuchs stood with a bloodied face on the steeplechase track, he was already an avid reader of Šot and Malárie, and also of the anarchist bulletin A-contra. He took part in a few anti-racist demonstrations and skirmishes with skinheads, but nothing opened his eyes like his experience at Velká Pardubická. It completed a circuit whose components had been loosely in place for some time already: from loud and activist hardcore music to Xeroxed magazines to the final "few whacks from a choleric cop". That lead him to establish his own magazine, which was something he wanted to do for a long time, and later lead him to starting his own band, Mrtvá budoucnost (Dead Future).

With help of contacts from Malárie, Fuchs published the first issue of Hluboká orba in 1993, soon after the Czechoslovak federation broke up. One hundred fifty copies of the fanzine were published with tens of pages in A5 format. As did his samizdat role models, he transcribed the texts at night: first on a typewriter, later on a computer. He printed everything on copy machines until the arrival of new technologies in the new Millennium. In his "seditious pulp magazine", as he used to call it, he would argue with fans who, according to him, got his "absolutely clear" words wrong.

Fuchs printed invitations to demonstrations, articles about the "toxic" influence of mass-media, and interviews with bands from all over the world, These bands were connected to the underground network, bands who refused to have music as a business and who were prepared to receive a few hits for their opinions. The hippie and beatnik generation either felt too tired, phoney, or artsy to American hardcore fans. Fuchs felt the same way, despite a certain affection and sympathy for the pre-revolution Czechoslovak underground: "Underground wasn’t exaggeratedly uncompromising and critical to the injustice of the world."

The early 1990s was a wild time. On one hand, the limitless economic possibilities were celebrated, on the other hand, a new battle against them was brewing which even got the attention of the anti-extremist department of the police. In the Nineties, there were protests against circuses, animal testing, the army; there were demonstrations against the opening of the first McDonalds and against globalisation. Activists got detailed information about these from Hluboká orba. It wasn’t the only fanzine of the Nineties, but it stood above the rest through its graphic design and extensive texts. Readers learned about police brutality, of autonomous centres throughout Europe, or of the practices of Shell petrol stations; they could read translated interviews with left-wing thinkers like Noam Chomsky, and appeals such as: "Turn your brain on – turn your TV off!"

The Internet didn’t exist, and there was incredible hunger for information, even little things like finding places with vegetarian meals, because meat-free cuisine was an anomaly in the Czech lands. Fanzines were piled up on tables at concerts together with political leaflets, and were distributed by volunteers outside of concerts. Hluboká orba and Malárie were published by the thousands. "When I first started being a punk, there was no Internet. I read all the zines I could get my hands on, and it really made sense to me to live in accordance with the thoughts present in them", one hardcore-punk fan recalls.

He wasn’t alone. Others like him began to take an interest in politics or ecology, started forming bands—and published fanzines of their own. Some kept up their enthusiasm, others lost it after a few issues, or it would be transformed into something else. Some used their experience with fanzines to work as graphic artists or writers, others were primarily interested in music publishing or in non-governmental organisations. Fuchs saw them come and go, but he remained, and his words could still arouse zeal across generations.

Some illness

At the turn of the millennium, protests against globalisation were at their peak, and a large march was being organised against the September 2000 Prague meeting of the International Monetary Fund. Before this IMF meeting Fuchs wrote in Hluboká orba that when it’s all over, the protesters would be written about by the mass-media as those, "…who only arrived for a fight, who don’t understand anything, who have inferiority complexes, are frustrated, manipulated, bribed, of course uneducated, fanatical, drunk/drugged (mustn’t forget that)."

Whether his predictions came true or not, he couldn’t have expected the march to turn into an out-of-control street battle, opinions on which varied even amongst its contributors in the next issues of Hluboká orba. According to some sources, approximately 12,000 demonstrators arrived in Prague; they were faced by 11,000 police officers with protective shields. Contemporary videos showed an urban battle scene. Tanks patrolled the streets, fires burned, cobblestones flew through the air. The protests gave many people the same impulse that the events of Velká Pardubická did ten years prior, and afterwards a third fanzine generation emerged. One of the most influential fanzines at the time, when the Xeroxed look began to face competition from computer design, was Bloody Mary.

Blood Mary’s co-founder Emča Revoluce (Emma Revolution) had a strong urge for self-determination, just as Fuchs once had. The unrest gave her courage, even though she participated in demonstrations ("mostly the animal ones") as an activist for many years. "The older I get, the more I see it as being naively messiah-like. A lot of things pissed me off back then though. For me, the important things were feminist things that I had direct experiences with— like someone bothering me on a train or having a problem with me considering myself a feminist, asking if it was a disease of some kind", recalls the thirty-year-old.

She wasn’t alone; with like-minded girl friends, she began publishing Bloody Mary, a notable femi-punk fanzine with a direct slogan: "Troublemaker girls of the world, unite!" The fanzine published extensive articles about protest groups, texts bordering on feminist studies, light-hearted manuals for DIY sex toys, and excerpts from the history of the riot grrrl punk movement. Riot grrrl gave courage to many a female punk in America during the late Eighties and early Nineties: to pick up a guitar, to start bands, to not just be the girlfriend of someone in the band. Bloody Mary did something similar over here.

Writing helped Emča deal with her own identity while at the same time she "loved the freedom of expression and hated commercials, which she had no need for." Bloody Mary was financed through sales and fundraising concerts. For 14 issues, the fanzine kept a light-hearted approach, mocking "girly" magazines and borrowing from their linguistic style. "As I got older though, the format stopped suiting me —the brazenness and tongue-in-cheek attitude didn’t really feel natural anymore", she explains, which is why she stopped publishing the fanzine in 2011. Since then, she’s been active in organisations helping homeless women.

A lost battle?

The original aim of zines —to provide important information quickly— began to lose importance with the onset of the Internet. Fanzines started to have a more important mission: to hold together a scene and a few hundred co-conspirators. In 2011, there was definitely no doubt about it. Fanzines became more documentaries of the times, scene chronicles,and Filip Fuchs understood this before everyone else. He switched to A4 from the smaller format in 2002 and published Hluboká orba once every two or three years, but then it had almost 200 pages of content; besides band diaries from tours and regular columns, hundreds of record reviews were also featured.

"In a way, it’s a battle with today’s mushiness, fragmentation, fluster. Probably a lost one though", he said in an interview with me in 2015, tiredness and scepticism clearly audible in his voice. "In the Nineties, you bought a mag, read it and then immediately sent a multi-page handwritten letter to its publisher. Today, communication’s much easier, but it looks like people aren’t communicating much, surprisingly."

Nevertheless, there are still tens of fanzines being published in the Czech Republic and it’s the hardcore punk community that happens to be the most persevering in this respect. Its members tend to cling to proven rituals and have a distrust for social media and smartphones. A month doesn’t go by when a hooded boy or girl won’t ask a gig goer: "Do you want to browse through my fanzine?”

Fuchs, a "member of the anti-TV movement" (as he was once described in the media), never gave up, and he continued to print his fanzine on paper until he died. He published for hundreds of his readers, but also for himself. The most fervent reader of Hluboká orba was admittedly Fuchs himself. The moment he looked forward to the most was when interviews with bands from all over the world began arriving, and he couldn’t wait to read what was in them. "Even though it ate a lot of his time, if he didn’t play in a band and didn’t do the fanzine, it wouldn’t be him anymore", recalls Fuchs’ wife Kristýna. At home, he would tell his daughters stories about pals—stories from Brazilian or Japanese tours with his second band See You in Hell.

He had a crush on a girl once, but because she smoked, he, as scrupulous straight-edge guy, sent her a typewritten admonition letter. He would reply to fans in similarly overblown and explosive fashion, be it with enthusiasm or irritation. He had made many enemies this way. He also wanted to be able to defend against injustice, so he learned to navigate legal waters, studied law, and worked his whole life as a lawyer for the Roma community in Brno. When he died in January 2016 at age 40 his obituary was published next to the obituaries of local Roma.

The last issue of Hluboká orba was published posthumously in December 2016. Fuchs himself prepared the issue, but his closest finished it. The fanzine was the thirty first issue. It is a unique story not only in the Czech Republic; there are very few zine publishers in the world who have had such stamina. The influential United States magazine Maximum Rocknroll has published since 1982, but is a team effort of volunteers from all around the world; Hluboká orba was always kept alive by the enthusiasm of a single person. It truly was the "Holy Bible of Hardcore Punk", a statement that once appeared, with typical irony, on its cover.

"A DIY fanzine is the true thrown down glove to mass-media, but that’s probably a Don Quixote slogan, a bit like the whole hardcore-punk rebellion", Filip Fuchs said in his last interview (with me for my thesis). But his scepticism didn’t mean he was leaving the scene for "normal life", as he wrote in one lead article. In over 30 years, he saw many such decisions, and never hesitated to sharply criticise them.

As he recalled in Hluboká orba issue 29, he gained a lot of courage from his past experience: "Sure, back then at 17, I could have perhaps helped a bit with the general stealing and swindling and now be sorted for life, but those few hits with a baton definitely sent me in a completely different direction. Once again, thanks for them!

I Shout That’s Me: Stories of Czech Fanzines From the 80s Til Now, is available now