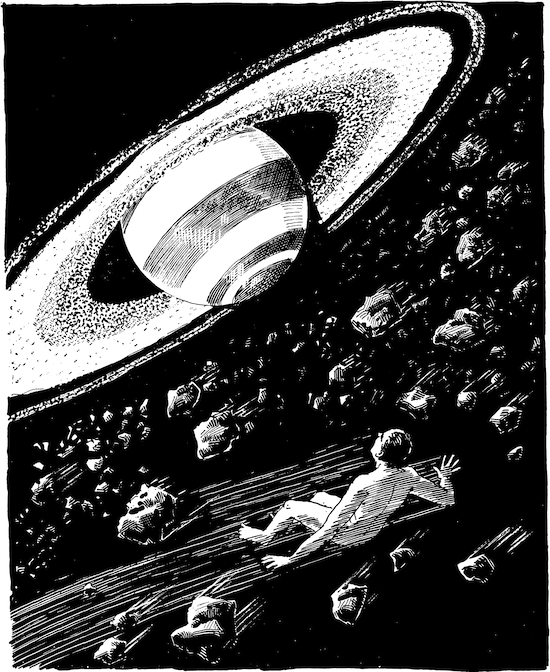

An illustration from HG Wells’ ‘Under The Knife’ published by Amazing Stories, 1927

”Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) –

Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.”

Philip Larkin – ‘Annus Mirabilis’

The flavour of Philip Larkin’s ironic ode to the sexual revolution of the sixties is triggered synesthetically by the subject matter in Mike Jay’s excellent new book Psychonauts, way before it turns up as an actual literary reference in the closing chapters. Such is the deathless, bony grip of the boomer on the public imagination – still – that it’s hard to even consider the modern history of narcotics without subconsciously arriving directly at the period where the beatnik counterculture of the 1950s gives way to the hippie counterculture of the 1960s. And this is understandable. Despite the stories of the rise and fall (and more recently the rise again) of mescaline, psilocybin and LSD, to name but three psychoactive substances, being retold to the point of feeling slightly threadbare, there is actually still much to say on the subject.

Recently, I have enjoyed and gained much from Michael Pollan’s How To Change Your Mind: What The New Science Of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, And Transcendence – especially in its clear-headed, engaging summary of how LSD actually works via the Default Mode Network – and Matthew Ingram’s Retreat, an incredible piece of research showing how the counterculture essentially paved the way for the billion dollar wellness industry of today. Both books are great, yet still represent a kind of reboot of the head books a lot of us came of age with… Aldous Huxley’s The Doors Of Perception, Jay Stevens’ Storming Heaven: LSD And The American Dream, and so on.

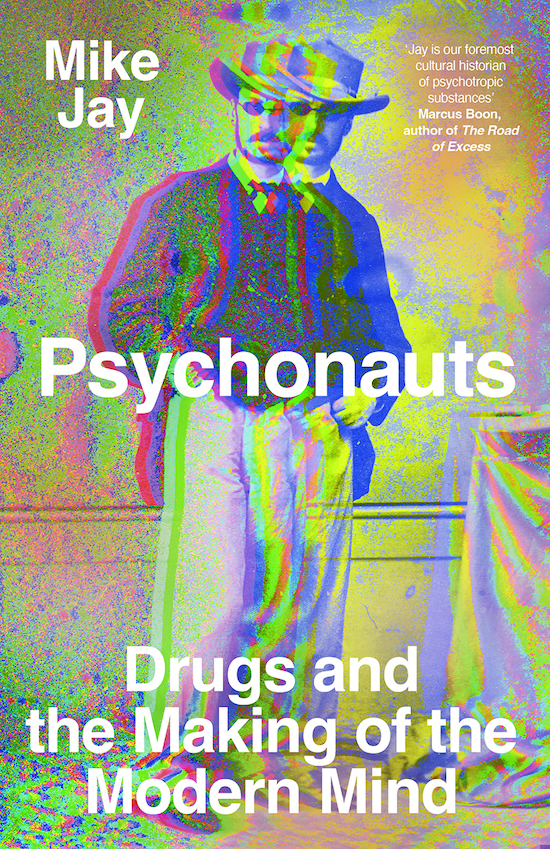

Psychonauts, published this week by Yale, offers a vigorous corrective to the casually accepted vibe that “drugs began” in 1963. A science and history writer by trade, Mike Jay has written original-research-heavy titles about such varied topics as schizophrenia and military history in the past but has notable form when it comes to drugs and is responsible for the excellent Mescaline: A Global History Of The First Psychedelic among other titles. There is a sense, however, of this being his ‘greatest hits’ – pun intended – and possibly represents him drawing a fat line – you feel me? – under his documentation of the subject. In short, he takes us on a whistle-stop tour of the early discovery/synthesis/industrialised refinement of such various substances as cocaine, nitrous oxide and ether, injecting – I’ll stop now – a wealth of well-sketched anecdotes into proceedings.

What we are presented with is the portrait of an age where scientists were keen to experiment upon themselves and how these experiments sometimes led to flashpoint moments of advancement in science, philosophy and art; and at other times led to accident, illness and early death. And in these descriptions of travelling medicine shows, rowdy music hall acts, 19th century laboratories, the birth of psychoanalysis, the advent of modernism, the uncharted frontier of analgesia and anaesthesia and the demi-monde of Paris, we sense times which were in many ways wilder, more exciting and more revolutionary than the 1960s.

The book, of course, has one laser eye trained on the landscape of 2023, and is organised in a way that allows the reader to easily draw useful links between, say, the convoluted origins of nitrous oxide as an aid to dentistry and the current ‘hippie crack’ driver of red top newspaper sales. (Although we have to infer how Jay feels about Cocaine Bear.) It is structured around many of the questions we ask ourselves today, so one section deals with the idea of cognitive enhancement, while another concerns the journey to the outer edges of consciousness, which suggests that some who use DMT and ketamine today are perhaps not so different to those who used nitrous oxide and chloroform generations earlier.

The term “psychonaut” was initially coined by the German writer Ernst Jünger in his work of speculative fiction, Heliopolis (1949). That Jünger survived World War 2 to write the book is surprising given his ambivalence to the Third Reich. While stationed in Paris, he befriended Picasso and Cocteau and passed some intelligence to the resistance – and his relative proximity to the Stauffenberg bomb plot. In his novel set in a future city state in the Mediterranean he describes a cadre of scientists – psychonauts – who synthesise new drugs and experiment upon themselves in order to investigate the hidden recesses of the mind. Jay, who is speaking to me from his home in Cornwall, laughs: “It’s handy, as that’s pretty much what my book is about, it’s just that these real characters I’m writing about existed many decades earlier.”

Jay says that he first encountered the term in relation to the psychedelic counterculture, a tag that tended to be awarded in a process of self-identification. “It was always loaded with this assumption that the person [saw themselves as] a rebel, a renegade or an edge lord, working far away from institutional science,” he explains.

“I wanted to reclaim the word. So if you go back before the 20th century, then yes, these characters were still rebels and renegades and all of that, but they were also institutional scientists, doctors, and pillars of the establishment. And pretty much everyone was a self experimenter, as this was an age when scientists used to self experiment with everything. They passed massive electric shocks through their bodies, or inhaled toxic gases. Drugs were the least of it, really.”

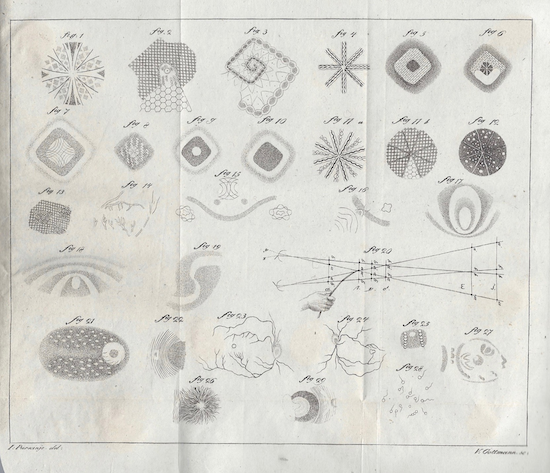

Johann Purkinje’s Observations And Experiments On The Physiology Of The Senses, 1823

I bring up Larkin’s ‘Annus Mirabilis’ with him, specifically the idea that the ‘auspicious years’ of this story are 1882 (William James’ intoxication with nitrous oxide) and 1846 (William Morton’s first forays into using ether as anaesthetic) rather than 1963, and Jay agrees that Psychonauts is, to some degree, a corrective to received wisdom:

“Like most people, I grew up with the vague assumption that drugs appeared in the 1960s,” he begins. “And that comes with another assumption that before the 1960s they’d always been banned, and they’d always been illegal. It took me a while to realise that what we think of now as the war on drugs – drugs being outlawed and demonised – was something that didn’t really happen until the 20th century.

“In fact the word drugs itself, in the sense we’re using it now, didn’t really exist until the 20th century either. Before that we were talking about a range of things that might include herbal medicine, research substances, anaesthetics, or simply items you could buy from the pharmacy, because, of course, cocaine, heroin and cannabis were all on their shelves along with all the other analgesics and stimulants and sedatives.”

Jay points to Thomas De Quincey, the author of Confessions Of An English Opium Eater (1821) as being an “early to the game” psychonaut. His most famous piece of writing describes the mechanisms of addiction and withdrawal before some doctors even understood what these things even were. Despite coming out of a period of romanticism, he was already pointing ahead towards the modern age, suggesting stubborn, hard to access subliminal depths to the human psyche. “He didn’t use the word ‘unconscious’ but that’s what he was writing about,” Jay continues.

Théophile Gautier, author of Le Club Des Hashischins, photographed by Gaspard-Felix Tournachon, c. 1840

One of the big shifts in the book happens in the second half of the 19th Century, in the run up to the rupture of modernism. One of the hallmarks of this movement in art, literature and philosophy was the shock of the new, a desire for novelty and new experiences that mirrored the ever changing, industrialised pace of life. Changes in attitudes towards drugs in this period were happening at a very rapid pace simultaneously with all of these other changes.

“The stakes change. The costs and the benefits both get ramped up at the end of the 19th century,” Jay explains. On the one hand, it’s a great era of discovery when it comes to the mind, but in another sense, the production of drugs becomes industrialised. They are pumped out in unprecedented volumes, they become more concentrated and there is the introduction of the hypodermic needle; plus they are now sold by pharmaceutical corporations. At this point they are products of big pharma.

“All of the anxieties about modernity come into play when people are thinking about what the role of drugs in society should be. There’s a new process regarding psychology and access of the unconscious and the subliminal mind and how you can get to it very directly. William James, through his experiences with nitrous oxide, shows this, and this brings in a kind of pluralism. As he says, in Varieties Of Religious Experience, our waking consciousness is only one particular type of consciousness – there are all these other types of consciousness which can be accessed if you huff some gas, or take a snort of this powder, or have a smoke of that herb. And these are different worlds where our sensations and perceptions are altered and things look very different.”

He goes on to say he thinks drugs played into "that specifically modernist sense of wanting to break the frames of time and space”, or “the way that things are normally presented.” This affected everything from cinema to art: "The idea that you can take a single moment and freeze it and break it down to nothing or show it from multiple perspectives all at once. I think those are the kind of ideas that emerged from the investigation of drugs in the late 19th century that feed into modernism.”

One of the very problematic aspects of modernism is its worship of power and the susceptibility some of its adherents had for looking for a strong leader to solve their problems. Modernism wasn’t fundamentally or explicitly fascist but it loaned itself quite easily to a fascination with totalitarianism. Right across the board from DH Lawrence to Ezra Pound via TS Eliot, Wyndham Lewis and HG Wells, this urge was undeniable, and as a group tenet it can be seen as much in the work of the futurists who fell in step with fascism as in the constructivists who fell in step with communism.

Another hallmark of modernism was the desire for a clean break with the immediate past, meaning this generation of artists and writers had a different relationship to the idea of drugs than the preceding generation of romantics. He explains: “Many modernists set themselves up against the decadent individualism of the 19th century. They would look at these drug experimenters [such as Baudelaire and Nerval] and say that their world had died in the 1890s. The days of huffing ether and eating hashish were over.

“[Filippo Tommaso] Marinetti of the futurists was obsessed with speed and became a fighter ace in the second world war – there was no problematic hidden, deeper self as far as he was concerned, just his ego intensified. And for people like this new drugs came along like cocaine and amphetamines which were more compatible with how they saw the world.”

It is during the modernist period that the progressive age begins, and the idea of the bohemian drug user becomes less important and at the same time psychology becomes less about introspection and more about measurement and behaviourism and the idea of social control. “The work of drug literature that really captures this era is Brave New World because Huxley’s soma is a product of a big pharma industrial process,” Jay explains. “And it’s given out to the masses to keep them sedated and stupefied in order to stop them from thinking too much. And that becomes the public image of drugs in the early 20th century.”

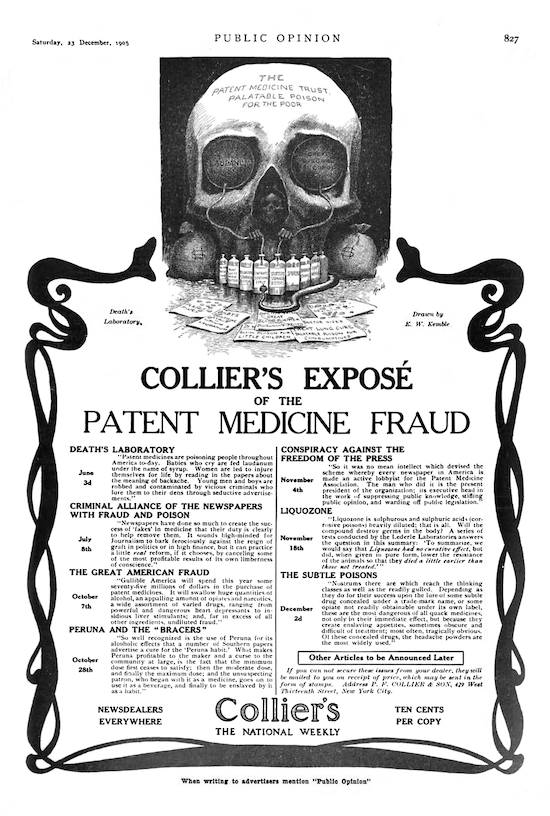

Advert for Collier’s Magazine on patent medicine fraud, 1905

The book has a clear view of the current landscape and there are numerous ways in which we can see how contemporary attitudes, approaches and fears are either at odds with how things were 200 years ago or remain as part of a cultural continuum. The chequered history of laughing gas especially should be of great interest to many readers today: “There were popular nitrous oxide scenes in the 19th century, with the idea of everybody getting together, huffing balloons and looning around. There’s a curious thing about nitrous oxide to do with economics though. It’s hard to synthesise so it wasn’t a thing that people did at home. But if you were a showman you could run a nitrous oxide event at a carnival or in a theatre, and once you had laid out the money for a tank to hold the gas in as well as the process of synthesis, you could then make a lot of money selling individual balloons.

“It didn’t actually spread in the 1960s despite the hippies, the bands like the Grateful Dead who travelled round with canisters of it, and despite various Hollywood poolside parties. It wasn’t until we developed those little canisters they have today [for the catering profession] that it became easily transmissible. It became democratised. But the balloon isn’t new. The drug has returned to its roots. [The chemist] Humphry Davy was huffing from a balloon over 200 years ago.”

As something of a thought experiment I typed “nitrous oxide” into the search function on my podcast app and listened to the first two listed results in preparation for this interview. The first was an episode of Dr Suzi Gage’s Say Why To Drugs – a short podcast with a relatively sober yet casual approach which said that, in the greater scheme of things, the gas is relatively safe to use, if taken with certain precautions. The second was produced by ITV and could have been talking about an entirely different substance. The Hieronymus Bosch-like mental image being created was one of Amsterdam hospitals overflowing with teenage stroke victims, avoidable deaths by heart attack and young amputees. It felt – if you were of the mind to accept the findings of the first podcast as more reasonable and more truthful – like nothing short of a return to the age of Reefer Madness scare-mongering.

I ask Jay if much has actually changed on this score. “It’s a lot easier to find a spectrum of opinion than it used to be when I was young,” he begins. “With nitrous oxide, I think the discourse around it at the moment is very shallow. It’s a bit like vaping – both of them are relatively harmless. And I’m only saying relatively compared to the things they’re replacing – they’re not entirely risk free of course.

“In the case of vaping it’s smoking cigarettes that is being replaced and in the case of nitrous oxide it’s glue and solvents. These are sensible harm reduction alternatives, but they’re both public nuisances and very visible; and it seems to me that’s what a lot of the conversion is actually about. Older people don’t like seeing younger people blowing out huge clouds of vape smoke, and they don’t like having to step over empty nitrous canisters on the pavement.”

It’s one thing drawing links from the drugs culture of 150 years ago to the drugs culture of today, but what about the things that lie around the corner? We’re in a time of great flux at the moment as regards substance use. Psychedelics are in danger of gaining a veneer of respectability, but to what end? Hedonism, the treatment of trauma or the user becoming a more efficient worker? And how is this brave new world stacking up for people of colour and the precariat/working classes, or the masses currently incarcerated worldwide for personal possession of drugs? If we follow in the massive wake left by America, we can expect some kind of soft legalisation to happen in this country over the next decade: how do we prepare for it?

Jay says there are notional lessons to be learned about what happens next from the characters who populate Psychonauts but says they would have been of greatest benefit to “the legislators, the bureaucrats, the statisticians and social scientists of the early 20th century who created the idea of ‘good drugs’ and ‘bad drugs’”.it is the framework of “drugs” itself which needs to be dismantled.

“If we could get rid of that [umbrella term] then maybe we could start talking about stimulants, for example, as a category,” he muses. “However, that would be a category which would include Adderall, a cup of tea and methamphetamines. Are we ready for that? But let’s look across all of the different categories, and try and raise general understanding; and then it’s time for an evidence-led process of trying to minimise harm to users and to also reduce those government policies which create harm.”

Extract follows below

Psychonauts: An Extract

Nitrous oxide’s enduring nickname, ‘laughing gas’, was in use by 1824, when it featured on the poster for a variety evening at London’s Adelphi Theatre offering ‘Uncommon Illusions, Wonderful Metamorphoses, Experimental Chemistry, Animated Paintings etc.’. The conventions of the popular nitrous oxide show were rapidly established. A master of ceremonies, usually adopting the persona of a scientific educator, would present the laboratory equipment, describe the chemical properties of the gas and ask for volunteers to inhale it. Often the first pick would be a collaborator who would scoff loudly before submitting himself (women were not permitted) to a lungful of gas and proceeding to behave outrageously – pirouetting, spouting poetry, spoiling for a fight – to the delight of the audience. More volunteers would follow, each attempting to outperform the last.

The effects of the gas proved far more spectacular on stage than in the laboratory. The first recorded nitrous show in the United States took place in Philadelphia in 1814 and was described by a local printer and pamphleteer, Moses Thomas, who gives a vivid sense of the proceedings. The experiment was part of a weekly lecture series, and the stage that evening was blocked off from both the laboratory equipment and the audience, heightening expectations of the unexpected. It opened with a doctor discoursing on ‘the nature and properties of nitrous oxide’ and demonstrating ‘a number of unimportant experiments, to which very little attention is paid by his auditors’ before he launched into the promised spectacle. The first volunteer, a young man of fifteen, was presented with ‘a large bladder’ filled with ‘the exhilarating gas’, which he inhaled, and then

‘…suddenly threw away the bag, with an air of triumphant disdain, and began to march about the inclosure with theatric strides, until coming up close to the front row, he perceived that one of the persons sat there held a cane athwart to defend himself from his too near approach. This offended his pride – he instantly burst into a paroxysm of rage: ‘That tyrant’, says he, ‘has seized my cane – deliver it to me – this – instant – or I’ll be the death of you!’ At the same moment jumping over the desk, and grappling with the man who had the cane, he overturned every thing that stood in his way, and it required the united efforts of four or five men to hold him down, till the effect of the gas ceased, and he turned round to the company with an air of good-humoured hilarity.’

More volunteers followed, and exhibited ‘different degrees of animation, or ferocity, dancing, kicking, jumping, fencing, and occasionally boxing anyone that stood in their way.’ The gas allowed the conscious mind to escape from the shackles of the body, but in so doing it left behind a body at the whims of unpredictable or automatic forces. These often seemed to release a second and hidden personality, which the popular lecture format mined for entertainment in a manner similar to the stage hypnotism shows of today. On stage, the subject’s inner experience on the gas was incidental; the setting was constructed to make the most of its external manifestations. The moment of return to waking consciousness was not interrogated for mystical revelation, but held up for confused hilarity.

Nitrous oxide was ideally suited to the travelling carnival-show circuit that expanded across the wide and sparsely populated interior of antebellum North America and Canada. It could be presented as both a miracle of modern science and a raucous entertainment, a novelty, both mind-boggling and edifying, that could play out every night for years in front of a fresh and astonished crowd. The gas tank, tubes and breathing bags required a capital outlay that placed the entertainment beyond the reach of private individuals, but thereafter the profits per dose of gas were considerable. The poet Robert Southey’s line comparing the gas to ‘the atmosphere of heaven’ was the perfect advertising slogan, frequently blazoned across marquees and posters. Entrepreneurs, innovators, medicine men, hucksters, grifters, mountebanks and frontier individualists of all stripes turned their hands to it. In 1832 the eighteen-year-old Samuel Colt toured a nitrous oxide show from Canada to Maryland, complete with mobile laboratory, under his old family name of ‘Coult’: he dosed an estimated 20,000 volunteers at 25 cents a time, using his takings to fund trials and prototypes of his repeating revolver pistol.