At home in a faded "Dan Dare- Pilot of the Future" t-shirt, Mick Farren is casting a rheumy eye over his illustrious past. The occasion is the publication of Elvis Died for Somebody’s Sins But Not Mine (Headpress books) – an impressive, career-spanning anthology of Farren’s writings, from his early anarchist broadsides for 1960s London’s leading underground paper IT (AKA International Times, which Farren also briefly edited), to interviews and editorials for NME in the 1970s, to his current output of fiction, poetry, online articles and more.

Attractively illustrated, and with a new introduction and sidebars in which Farren comments on the selections from a contemporary perspective, the volume also includes excerpts from the author’s several books on Elvis Presley, and his many works of original, unhinged science fiction, including 1973’s Texts of Festival, 1978’s eerily prescient The Feelies, and the mind-blowing DNA Cowboys trilogy (which naturally runs to four volumes). It also draws heavily on his columns for LA Citybeat, LA Reader and the Village Voice (Farren moved to the states at the dawn of the 80s, returning to the UK three years ago for health reasons), covering the political nightmare of the Bush years (and the Clinton interlude)in razor sharp, blackly humorous vignettes that invite favourable comparisons between Elvis Died for Somebody’s Sins and Hunter S Thompson’s The Great Shark Hunt.

Highlights include Farren’s 1976 NME polemic ‘The Titanic Sails at Dawn,’ one of the few pieces of rock writing to be regularly cited as being of historical significance and impact, its wake-up call to the jaded, bloated rock elite of the time and demand that the kids on the street take back the music that was rightfully theirs now widely seen as contributing to punk’s cathartic eruption. Throughout, Farren remains committed to the idea of rock n’ roll as part of a broader revolutionary impulse, with an inherent significance that wasn’t gifted to it by Dylan or Sergeant Pepper, but was there from the first cry of A Wop Bop a Loo Bop onwards.

An irascible idealist, arch-mischief maker and thorn in the side of both the establishment and the hippy high society, the afro-haired, leathered-up Farren ran the door at the legendary UFO club through the summer of love, then threw himself into the midst of the summer / winter of protest and discontent that followed. Fronting his legendarily unlistenable (but actually great) experimental rock band The Deviants, he played the 14 Hour Technicolor Dream alongside Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd, and opened for Led Zeppelin on their first UK tour (when both they and Zep were bottled offstage by irate farmboys). Farren wrote lyrics for his Ladbroke Grove homies Hawkwind and Motorhead, instigated the storming of the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival (which he memorably described as a “psychedelic concentration camp”), and organised his own Phun City Festival the same year, bringing the MC5 and William Burroughs to the outskirts of his childhood home of Worthing- an act of sweet revenge that’s widely regarded as a catalyst for the UK free festival scene that followed. As co-publisher of underground comix anthology Nasty Tales, Farren also won a precedent-setting victory against obscenity charges at the Old Bailey, representing himself without the aid of expensive lawyers. Not bad for a skinny street freak whose only ambition was to avoid the career in advertising his art school education seemed to be herding him towards.

These days, Farren’s blog Doc 40 provides a regular dose of political commentary, rock n’ roll, conspiracy theorising and weird science (once you get past the Google objectionable content warning), and his most recent novella, Road Movie (Penny Ante Editions, 2012), showcases a post-modern, freewheeling poetic prose that is part existential apocalypse thriller, part nightmarish satire and part 3am fever visions. Now 69 and somewhat less mobile than he once was, Farren nevertheless still performs as a poet and fronts the current line-up of the Deviants, featuring original rhythm section Russell Hunter and Duncan Sanderson, plus long-term guitar foil Andy Colquhoun and percussionist Jaki Windmill.

Perhaps operating simultaneously as an author, journalist, poet and singer is one reason why Farren has never quite received his historic dues; an altogether admirable impulse to forever bite the hand that feeds him is another. I spoke to Mick at his Brighton flat for the best part of three hours, covering a multitude of subjects including why his great hero Elvis Presley is still the fertility god of the twentieth century (but buy the book to read more on that), and getting drunk with Jim Morrison in London’s Chelsea Potter pub (“It wasn’t much of a meeting of minds… he was out of his fucking gourd”). But I began by asking whether he or publishers Headpress had the initial idea for the anthology.

Mick: It started off with them asking if I wanted to republish stuff, and I said no, not really, because we’ve got to get rights back and shit, and they didn’t want to do too much fiction. They’d just republished Guitar Army by John Sinclair, and John as usual was dicking them around, John being the laziest man in show business, although I love him dearly, but he don’t get a lot done. So we sort of talked it through and eventually they said well, why don’t you do a sort of greatest hits? That’s cool, okay. And then I went away thinking where the fuck is all that stuff? Because when I moved to the states I left a lot of stuff with my mother. And her house got damaged in the South Coast hurricane, and she took some of her stuff and also my stuff and put it in a storage facility. And that was fine, until she got Alzheimer’s and didn’t remember where the storage facility was. And so somewhere in the world there’s a complete set of ITs, Oz’s, old NMEs, all kinds of shit. So I had to contact the fanboys, and bit by bit I managed to get together what I wanted to re-publish, and also a whole load of shit that I’d completely forgotten.

This was about four years ago.

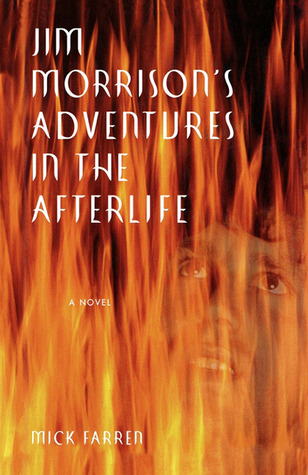

Mick: Yeah, it’s taken that long. Headpress are basically two guys and a dog, but they do lovely work. It’s a better world than the major New York publishing houses, which are absolutely a complete waste of time. All they want to do is find the next Harry Potter, and when there’s an anomaly, like the 50 Shades of Grey phenomena, they’re almost unable to handle it. There’s all this “oh, print is finished…” Yeah, well it wouldn’t be so bad if you motherfuckers weren’t so fucking incompetent, you know. One of the great banes of my life is that I wrote this beautiful novel called Jim Morrison’s Adventures in the Afterlife, of which I am incredibly proud. It really is Jim Morrison’s adventures in the afterlife; he’s mates with Doc Holliday, and Aimee Semple MacPherson turns up, and Dylan Thomas in the form of a goat. And it’s quite fun; there’s actually a scene where a guy who thinks he’s Jesus, and Dylan Thomas as a goat, are living on a tumour on Godzilla’s neck. I mean, I was having a great time, and Jim Fitzgerald, my editor at Crown Books, was allowing me to have a great time. And then they fired Jim, and Jim was like, 52, he had a couple of kids in college, and he was immediately replaced by some airhead who was getting paid next to nothing because it was prestigious to live in Manhattan in some kind of fantasy of Sex and the City or some kind of Rom-Com. And the book was actually published and promoted on Amazon as though I was actually channelling Jim Morrison. And then the shit hit the fan…

So they were actually promoting it as though you were claiming to be some kind of medium? Never mind that you already had an established reputation as a science fiction and fantasy author, who writes well-received books about stuff you’ve just made up.

Mick: Yeah. Well, a few months earlier somebody had brought out a book where they claimed they were channelling Jerry Garcia or somebody. There was a sort of spate of channelling books.

And they thought that they seemed to be doing quite well, so that was a good pitch?

Mick: That’s right. And there were also the kind of white light death experience books, all the angel books, and all that shit was coming out. And I sort of got filed under that. So thousands of copies went out to Barnes & Noble, and Borders, and the mass chains, and they all came back again, which completely ruined my reputation. And people who’d only read the promo thought I’d gone crazy, and altogether it was a very unhappy experience. It’s a great book though; it’s still there, and one day… I think I’ve got the rights back now, or I’m close to it. That’s another thing that takes years; you send all these memos to the legal department, and then you wait eighteen months and they answer it. And then you wait another eighteen months and they send you a letter saying you’ve got the rights back, and you can do something. I think the word is counter-productive. Capitalism is counter-productive to art, just as the Catholic Church was counter-productive to art four hundred years ago. It’s the same bullshit. And I’m sure Michelangelo didn’t want to sit around painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and Leonardo Da Vinci didn’t want to be doing Last Suppers, you know. He’d rather have been building a submarine, but the Pope wasn’t paying for submarines.

Looking at the work collected in Elvis Died for Somebody’s Sins, your writing style is fairly consistent. Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane and William Burroughs seem to be influences from the beginning.

Mick: That hard-boiled, Jim Thompson style? Yeah, absolutely. First of all, it’s not easy to do. It’s a bit like metaphorically learning to play guitar along with Lou Reed; it’ll put you into a very stripped down, meat and potatoes style of writing, which later I found transferred itself both to political rants in the underground press, and also it worked well as a rock writer. Plus then Burroughs came along, and Bob Dylan came along, and that didn’t conflict with what I was doing already, but it meant that level of surrealism could be built in, and that’s how it went, really.

It almost seems to sum up your differences with the other characters around sixties London, the flower child elite; that in your style and worldview you were coming from Chandler and Spillane, while they were all reading Tolkien.

Mick: Well, except in a sense I was part of the flower child elite as well.

Sure; but reading things like Jonathan Green’s oral biography of sixties London, Days in the Life, and your own memoir Give the Anarchist a Cigarette, it does seem that you rubbed a lot of people up the wrong way.

Mick: Oh, yeah. Essentially because I was just a little bit older, for a start. Only a matter of a couple of years, but it made a difference. It was like being in school. And I’d already got a grounding in Elvis Presley and Gene Vincent and Miles Davis, and the rougher end of the Beat Generation, and I’d seen Marlon Brando in The Wild One, and that was my heritage and baggage that I took to the psychedelic party. And it really wasn’t welcomed too much by Krishna’s Children. And yeah, there were some clashes. At the same time though, I was required. On the most mundane and simple level, I went down to the UFO Club one night and saw that things were a bit of a mess, and I went down a second night and saw that more people were coming and there were problems with skinheads, and I said to Hoppy [UFO co-founder John Hopkins], let me work the door for a bit, just to get this sorted. And I thought I was just going to work out a system for that night, but I worked the door at UFO amongst other things for as long as it lasted. It did get quite hairy at times. When it became really popular and moved to the Roundhouse there were all these- there was a big schism among the mods, some like Stevie Marriott took acid and were with us, and then there were the other ones who kept on taking speed and became Nazis with the Doc Martens and the shaved heads, and they were definitely not with us, and they’d try and crash the place every fucking Friday night. So we had all kinds of weird-ass security, from some of Michael X’s boys to a judo club, to the sort of proto Hell’s Angels. So within the hippy hierarchy I was Tony Soprano; I had my own little army, you know. But only for good! Which didn’t altogether sit well with some of them, but that was all over by at least the summer of 1968, when the big Grosvenor Square demonstrations started happening. We’d all really forgotten about the bells and beads and Hare Krishna; it was the Psychedelic Left, by then.

So people really got radicalised across the board pretty quickly?

Mick: Well, getting hit on the head and tear-gassed will do that for you. But at the same time it won’t get you trusted by the Socialist Workers’ Party. So I was incredibly distrusted then by Tariq Ali and Vanessa Redgrave, and the fact that I had an affair with Anna, Vanessa’s sister-in-law, didn’t help either.

Was it just that you were being outspoken, but that you weren’t toeing the party line?

Mick: Oh, I was absolutely certain of that. There was a feeling that I was like fucking Danton, you know! It was weird. The second Grosvenor Square riot, that day was very, very strange. I think the authorities were over-estimating what we were capable of, because it felt like Chile or something, and the overthrow of Allende. We came out of our house on Shaftsbury Avenue and there were motorcycle cops under the trees and little knots of police everywhere. I mean, nowhere near Grosvenor Square. And then there was all the fighting in the square, but at the beginning there was this eerie feeling of Jesus, is there going to be a revolution today? But I was always totally convinced that three weeks after the revolution they’d put me up against the wall and shoot me.

When you were younger, what was your first moment of political awareness?

Mick: When Elvis Presley came on the radio and my stepfather told me to turn that shit off! And then I went to a boys’ grammar school and the headmaster thought we were a minor public school, and we weren’t, it was just Worthing High School for Boys. Education was an us and them situation, and at that point in time I started reading everything I could, from Chairman Mao through to Bakunin… a lot of things I started and went, this is kind of tedious, you know. I mean political theory; I think I only got 28 pages into Das Kapital and decided I’d rather read I, the Jury. Hell, it was Johnny Strabler; “what are you rebelling against, Johnny?” “What have you got?” I was a rebel with plenty of causes. And after that, the only semi-organised movement I ever got involved with was CND. Because they had these wonderful, almost like moving rock festivals, these marches from Aldermaston to London, and there were girls who looked like Joan Baez, and it was great. And mercifully Bob Dylan came along so we didn’t have to sing ‘Down by the Riverside’ or ‘We Shall Not Be Moved.’ And even that went into it, the whole Judas, Bob playing electric, Pete Seeger wanting to cut the power off with an axe; that really was a symptom of something much bigger. It’s only been in recent years that I’ve coined the phrase the Psychedelic Left, but it was; there was a traditionalist, working class, well not even working class, it was a woolly, middle-class, sweater-wearing, Trotskyite whatever…

Middle classes who fetishized the working class.

Mick: Yeah, but there was no fun in it, no romance. And you had to dress ugly. And Bob put on a leather jacket and a telecaster and we thought, oh right, here we go, this it, this is what we want. And that was the big separating out, that was where Ewan McColl and most of the Trots, they took their sweaters and their Pete Seeger records and went home. And we just stormed on. And as we stormed on the first thing we tripped over was lysergic acid, and woah, where are we now. And the political thoughts of Baba Ram Daas and Leary and whatever got in the mix, and Uncle Bill [Burroughs] really got popular, and so it went. But there really was this schism between the conventional left and the psychedelic hippy left. I had tea with Tony Benn, because I’d had something in the Melody Maker, and he’d replied to it, and he invited me over for tea, and then he started delivering almost this little lecture and I didn’t take too kindly to that. But clearly he was putting out a feeler to see if us hippies might all join the Labour Party. Unfortunately I had tea with him on Sunday, and the following Saturday we disrupted the Frost Show, and I think that was the end of the dialogue between the Labour left and us freaks. I think he realised it really wasn’t going to gel together.

Fine man though Tony Benn is in many respects, he was also the guy who shut down the pirate radio stations when he was Postmaster General, which perhaps indicates a certain lack of sympathy with people who saw rock music as an instrument of revolutionary change.

Mick: Well, that’s what the article in Melody Maker was about, which he was kind of paying lip service to. But to use rock music as an instrument of revolutionary change, you’ve got to like rock music in the first place. You can’t go home and listen to Chopin, and just use it. That’s the important thing; that we weren’t tools to be used by anybody. We kind of liked what we were doing.

This brings us on to what’s seen as one of your signature pieces, ‘The Titanic Sails at Dawn,’ which is featured in the book, though rather unfortunately it’s dated wrongly; it’s credited as being written in June 1977 rather than June 1976, and obviously in terms of predicting the birth of punk that’s a fairly crucial difference. By June 1977 it was the Jubilee year and ‘God Save the Queen’ was at the top of the charts already. But it’s on record elsewhere as definitely having been published in June 1976.

Mick: Oh. Fuck. Yeah, it was kind of disingenuous anyway, because I was well aware that what I was calling for was already happening. There was a definite thread in what I was doing, and what my mates were doing- what the Deviants and the Pink Fairies and Lemmy and Hawkwind were doing, the Grove boys and elsewhere, it was heading for punk just like the Titanic was heading for the iceberg, except it was the iceberg. It made absolute sense that this was the next evolution. And we were already at the NME incredibly interested in Dr Feelgood and Kilburn and the High Roads, Eddie and the Hot Rods, and not treating them as some kind of retro phenomena like Sha Na Na.

What was the general editorial feeling about early punk at the NME? Were most of the staff and editors on board, or were you in a minority?

Mick: We started in a minority and took over.

Is this the guys who’d come up from the underground press?

Mick: Yes. And I think that was a very deliberate move on [NME editor] Nick Logan’s part. I think it kind of upset the old-timers who wanted to write about Yes and ELO and go to the parties and whatever. We went to the parties too, but… Nick Kent was still obsessed with Keith Richards and Led Zeppelin, so we weren’t completely out on a limb. I think me and Charlie were the furthest out on a limb, and also Chris Salewicz. And we were bringing reggae into the mainstream too, which was almost an equal part of it. I don’t know where punk would’ve been without Max Romeo and Junior Murvin and Marley, it was all part and parcel of the same thing.

Among you and the other writers who came from the underground press, there does seem to be a large amount of guilt about working for the NME. Someone starting out in music journalism today might find that guilt feeling odd, and would just see it as a natural progression…

Mick: Well, I wasn’t thinking about a career, for one thing. It was all hands to the pumps, let’s have an underground press, you know. Not to say that I didn’t learn journalism, because I did; I was particularly taken with New York sports writers in terms of style. But we were learning journalism in the very old-fashioned way; you went on the local paper and you covered dog shows, we went on the underground press and covered riots. Joe Stevens the photographer and I, we always felt vaguely guilty we weren’t in Vietnam, like Don McCullin or Michael Herr. But we weren’t, so what the fuck. And then Joey went off to Northern Ireland and got himself banged up in Crumlin Road Jail for three months because he’d gone out to photograph an IRA bombing, which seemed at the time a rather dumb thing to do, but yeah we were out there looking for adventure. But fuck it, you’ve got to remember that simultaneously the actual journalism, it’s changed back now but we had Lester Bangs and Hunter Thompson really changing the face of journalism, and Hunter wasn’t even a rock writer, he was writing about sport, although it was hard to recognise.

Did they put many restrictions on you at NME, in terms of what you could write about?

Mick: No, not really. There were the usual seven forbidden words, but it was more like IPC just tried to fuck with us. They made our lives difficult, but then we made their lives difficult by having Nick Kent, who hadn’t had a bath in two weeks, go in the elevator with the people from Women’s Own. And Charlie and I basically got drunk a great deal, and there was a lot of speed, and what IPC really did was basically wait for us all one way or another to burn out, and then replace us- this is 1980 or so- with something more in tune with the magazine work of the time. There was no personality, no style and that’s the way they liked it. It just moved on into, stick Nick Drake on the cover of Mojo and we’ll have a rock press. Oh, okay. By which time I’d moved to New York. I was still doing some music stuff for Bob Christgau at the Village Voice, but that was when I was in serious science fiction production with Del Rey, and also working on the ill-fated musical The Last Words of Dutch Schultz with Wayne Kramer, and drinking a great deal, because you can in New York, because the bars are open 24 hours a day if you know where to go, and having a wonderful time. Sorry, what were we talking about?

Some of the lyrics you wrote for Wayne Kramer’s solo albums are featured in the book; you became friends with him when you brought the MC5 over to play the UK for the first time, at the Phun City Festival in 1970. I guess that when you first heard the MC5 you must have recognised a kindred spirit to the Deviants?

Mick: Absolutely. Simon Staple, who had the record label that [Deviants album]Disposable came out on, and also worked on a record stall on Portobello Road, he came running out and said “come in here and listen to this”, and he played me Kick Out the Jams– wow man, they’re doing what we should be doing only they’re doing it better! And Howard Parker, who was the first manager at Dingwalls and before that was the DJ at the Speakeasy, the same thing happened. “Ah Mick, you’ve got to listen to this”, and he played me the first Stooges album, and I was yeah, they are doing the same thing we’re doing, and probably not doing it better. It was obvious there was a bunch of people who’d grown up on ‘Sister Ray’ by the Velvet underground plus Chuck Berry plus throw in a bit of Sun Ra; there weren’t very many of us, we were almost the sort of proto-punks.

That’s the thing with the Deviants; on the one hand you were just playing dirty rock n’ roll, influenced by the blues and Gene Vincent and the early Who, but on the other hand you were picking up on this avant-garde stuff that’s going in; you’d been listening to modern jazz and Zappa and musique concrete, so it wasn’t just dumb rock n’ roll, it was dumb rock n’ roll that was smart.

Mick: One of the differences between us and the MC5 was that we were listening to John Cage and Zappa and weird electronics and shit, and they were much more listening to Sun Ra and Eric Dolphy. But it was really all part of the same stew. And we knew about each other first of all, and then we actually met with each other and became friends. And there was Roky Erickson doing the same thing down in Texas but we didn’t actually know him, and the Blue Cheer in San Francisco, who I met later, who were nothing but loud, and the scary Kim Fowley; we were sort of scattered about, you know.

You took the musique concrete, Zappa, cut-up thing the furthest in your own work with your first solo album, 1970’s Mona, The Carnivorous Circus. That album is still being rediscovered by people, but am I right in thinking that you have memories of the time that you made it, that maybe cloud your own feelings about the album?

Mick: Yes, I was mentally ill at the time. The only bits I ever listen to are the Paul Buckmaster cello solo; I love that, and that was really a magical thing that just came to hand. The cut-ups and stuff, I think I could’ve made some better choices. They’re not things I listen to and go, oh yeah, that’s great, because I think I was just too tired and shattered and pissed off, and coming down off three years of being in the Deviants and pretty intense drug-taking and drinking. It makes me really happy that suddenly people are taking it seriously, because it’s a fairly serious piece of work. But I’m not sure that Van Gogh got up in the morning and looked at the crows and the bizarre clouds and went damn that’s a good painting, you know? No, he considered shooting himself, and one day he did.

I think people like it because it does obviously sound quite raw and damaged, at the same time as being brave and experimental. People appreciate it in the same way as Syd Barrett’s solo albums.

Mick: Yeah, I know exactly what you mean. But I never wanted to be Wild Man Fischer when I grew up. It’s hard; there are actors who can’t stand watching themselves on the screen, and that particular record I don’t listen to it apart from the actual title track. That long Buckmaster solo is lovely. He came down because he was a mate of Steve Hammond who was the musical director on that, and Paul played me this bit of Bartok’s string quartet number whatever, where he does something and there’s a slice of Bo Diddley, right in the middle of this Bartok string quartet! And we went right, we’re already doing this, we’re laying down this long mess of the Bo Diddley rhythm, would you like to saw away on top of it? And he said he’d fucking love to. It’d make a great change from going dink-dink-dink with Paul McCartney. And so we had a great time. That was a great time; that was really fun. Some of the other tracks, they were interesting, but I’m not sure I was exactly having fun. I was stone miserable, but I wasn’t hating doing it; I was loving doing it, but it’s just damaged and warped.

On your second “solo” album, 1978’s Vampires Stole My Lunch Money, you worked with amongst other people Wilko Johnson, who laid down his distinctive guitar playing on a couple of tracks. In light of his terminal illness, we should probably say something about Wilko.

Mick: Well, you’ve seen the films; live, he was a maniac. Off stage, he was a maniac. Him and Lemmy would go around not sleeping for days on end, and we had him bringing his black and red telecaster and doing the bits on Vampires Stole My Lunch Money.

Was it through Lemmy that you knew Wilko?

Mick: No, it was just around Dingwalls. I think our girlfriends, Ingrid and Maria, met each other, because oddly enough both Wilko and I are both kind of shy. And they conspired to get us together, and then he started coming around, because he always knew I’d be up; he’d come round in the middle of the night, sometimes with Lemmy, sometimes with Phil Lynott, sometimes with Jean-Jacques Burnel, and there was a coterie of speed freaks who had a list of people who’d still be awake at 5am, and I was one of them. And he came round a lot, after he quit the Feelgoods, because he was a bit bent out of shape by that, but at that point I went off to America and didn’t really see very much of him, and we just exchanged letters. I gave him this air pistol that belonged to William Burroughs, because I couldn’t see me getting it through customs. And both Wilko and I were very interested in the drug habits of the romantic poets; ‘Oh, Strindberg turned up today; three days later a Chinaman arrived with a packet of opium that was supposed to last us all winter’. This is the sort of conversations we had; it was the romantic poets considered as the Furry Freak Brothers. He’s just one of the crew, one of my mates. And he hasn’t played in Brighton, so I haven’t actually hung out with him since I’ve been back, except to talk on the phone, and now the motherfucker’s gonna die on us. Don’t get old, man; it’s like being in combat, people drop dead every fucking week. It’s very, very depressing.

There are excerpts from some of your novels in the book, which are broadly science fiction, but aspects of stuff you’ve lived through, and things that are going on in the world, and what could be termed counter-culture concerns, are always threaded through them.

Mick: Yeah, right. See what happens is, you write something, and I always think it’s pure fiction, because to get away from my stepfather I would go off to different planets, different worlds, and hide in my imagination. But then you read stuff back years later and think, oh my god, I was actually doing some bit on a real situation, but couched in fantasy drag, so to speak. I really don’t like talking about myself. This is fine, but I don’t want to write Prozac Nation. I mean, fuck it, I like to write adventure stories; that’s what I tell myself. But you can’t help letting your own personality, your own experiences, slip through. Nowadays I think I’m getting quite good at mixing it up, but we shall see. I think it’s the difference between Freud and Jung, actually; do you want to tell it straight, or do you want to make it into your own little cocktail. You get drunk either way.

You’ve got this in your first novel, The Texts of Festival, which has this great conceit about this post-apocalyptic society where the lyrics of rock n’ roll songs are treated as religious texts, mangled Dylan and Stones quotes and things, and it’s obviously a post-sixties wreckage, even though it’s at some unspecified point in the future. Or it’s like any rock festival that’s gone on too long, and everybody’s run out of money and drugs and food, and they’re fighting over what’s left, but you’ve just turned it into a post-apocalyptic western.

Mick: Yeah! Because that’s more fun than describing the Sunday at the Isle of Wight, which is actually where a lot of the imagery came from. I just stood there on the final day of the Isle of Wight Festival, and there are all these big fences, and half the stage is burning, everybody’s covered in grease and grime and dirt, and it really just looked like the Huns had sacked Constantinople or something.

That was the Isle of Wight Festival of course that many people hold you responsible for the barbarians storming the gates.

Mick: This is true. This is very true. Yes. I was looking round on the Sunday quite quietly pleased at my handiwork. I mean all we did was tell them there was a large hill where they could see the thing for free. And after that it kind of took on a course of its own. Ricky Farr and the Foulks Brothers were booking more and more acts to get more and more and more people; it was almost like a pyramid scheme, and it just got so big and so expensive, and the bill was so vast, and so many people had to come and so many people had to pay, I almost felt that at the end of it they were absorbing almost the entire budget of the counter-culture, it was all going into this ludicrous festival. That’s why Edward and I drove down there in the first place, pretending to be journalists, to have a look at how this thing was shaping up. And then we saw the fucking Berlin Wall, and thought, oh my god, this has gone too fucking far. And then we saw the hill… All we really did was put out White Panther Bulletin number 5, as though there had been four others, which there hadn’t, and wrote that there was a big hill there, and you can watch the thing for free. And then Ricky Farr calls me up and threatens to kill me, and life goes on. But yeah, blame somebody, and I was happy to be blamed for it.

The Deviants are playing a small festival this summer I believe, at Sonic Rock Solstice.

Mick: Yeah, we are. We’re still going; it’s just we’re a little inept at getting ourselves booked. It’s such a racket, and so many people want to work. When you go somewhere like the Robin in Bilston, where we played a couple of months ago, half the time they’re booking tribute bands.

Do you find a lot of audiences and bookers want you to be a museum piece and pretend it’s still 1969 or whatever?

Mick: Well, that’s what we tell the bookers, basically. Yes, that’s what they want. But it’s a moot point. I find it kind of spooky; these middle-aged guys, they’re a bit too young to have been there the first time around and they almost want it recreated for them. And we’re going, no guys, that’s not what it’s about, that was never what we were about. We were storming into the future. We still want to storm into the future.

Elvis Died for Somebody’s Sins But Not Mine is published 6th of May, by Headpress

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more