Born in 1939 in London, prolific science fiction and literary author Michael Moorcock became editor of juvenile magazine Tarzan Adventures when he was just 16 years old. Eight years later he went on to edit the New Worlds science fiction magazine as a key proponent of the New Wave science fiction movement in both Britain and across the pond. Known to friends as a charismatic figure with an immense presence, Moorcock served as a catalyst for many influential relationships – including introducing JG Ballard to artist Eduardo Paolozzi in the late Sixties. More recently, he penned a Dr Who novel and is currently working on his autobiography due out later this year. Nearly his entire body of work, both science fiction and non-genre, is being reissued and distributed in print and e-book by Gollancz beginning this month through January 2015 – veritably ending the Moorcock paperback drought.

An undeniably post-Moorcock author, China Miéville tries with difficulty to remember when he first came across the writing of the author. He becomes literary and muses, ‘I feel like he’s always been part of my mental landscape, like amazing rocky outgrowths drawn by Burne Hogarth.’ As thoughts of old Tarzan Adventures trigger Miéville’s memory he suddenly recalls, ‘It was probably The Stealer of Souls, when I was about 9. I remember the name ‘Moonglum’ with delight.’ Moonglum was Lord Elric’s sidekick, and they rode together like a veritable Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

As it was for many young fantasy readers, the Elric series was Miéville’s gateway drug to Moorcock’s expansive, genre-hopping oeuvre. Kathy Acker too explained how she grew up ‘weaned’ on Moorcock’s pulps. The Elric stories possessed a more European vibe than Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Martian books, Fritz Leiber’s Gray Mouser or Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth. They were written when the author was 21 or 22 years old and living in London in the Sixties. Some cling to this early pulp like mother’s milk; Dave Hardy, author of The Uprising of the Dead said, ‘When you fall in love with something at that age, you never quite outgrow it. Elric’s not just nostalgia for me.’

Similar to Miéville, Moorcock published from a young age and was raised mostly by women. ‘I see this as a plus’ Moorcock said of having a mother and grandmother who ‘set a high store on freedom’ when he was growing up. As a teenager in the mid-to-late Fifties Moorcock recalls spending nights playing guitar in Soho bars, he remembers: ‘I came to know quite a few of the women – both strippers and whores. I played guitar for a procuress called Eileen Fox who organised “private parties” for, as it were, visiting sailors. I usually got paid pretty well for the time. One party consisted of what seemed an entire regiment of Mounties.’ Interested in American blues and folk, Moorcock went on to later form his own psychedelic band, Michael Moorcock & The Deep Fix in the mid-Seventies. He wrote lyrics for Blue Oyster Cult alongside other BOC alumni Patti Smith and Jim Carroll. He even performed regularly as a member of Hawkwind in the Eighties and Nineties.

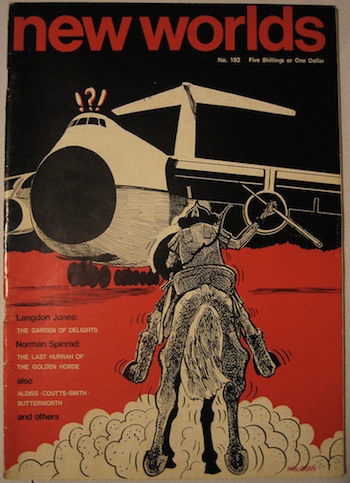

At age 24, Moorcock found himself at the editorial reigns of what had previously been John Carnell’s New Worlds monthly after editing Tarzan Adventures as a teen. With Moorcock now driving the bandwagon, New Worlds during the late 1960s and early 1970s evolved from a pulp science fiction magazine into a showcase for speculative fiction and pop artists, under the flag of New Wave science fiction which often incorporated found texts and collage. Moorcock’s aim was to radicalise pulp science fiction, which was riddled with space cowboys and hyperactive robots. Ballard remembered in his autobiography, ‘For years we had carried on noisy but friendly arguments about the right direction for science fiction to take. I believed that science fiction had run its course, and would soon either die or mutate into outright fantasy’. Ballard led speculative fiction with his characteristic paranoid genre-bending form, and Moorcock as his main publisher in New Worlds: The magazine printed an early version of Ballard’s Crash, in his short story ‘The Summer Cannibals’. Moorcock explained that speculative fiction sat neither with Utopian nor Dystopian fiction, but rather represented a ‘sophisticated visionary impulse’ expressed instinctively by writers.

One of these young speculative fictioneers Moorcock published alongside Ballard, William Burroughs, Thomas Pynchon, Brian Aldiss and Mervyn Peake was Michael Butterworth, who reminisced about the evolution of Moorcock’s own writing during his editorial era: ‘Mike applied his energy and inventiveness to the much more contemporary and serious literary vehicle of Jerry Cornelius’. Thinking of his and Moorcock’s shared inspirations, Butterworth added with a smile, ‘He often looks to the past for his inspiration – Meredith, Wells, Dickens, Brecht – but reconfigures their styles for a contemporary audience, always restlessly experimenting, the arte povera of writing’.

Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius short stories, published in New Worlds, acted as a parallel version of the first three Lord Elric shorts – an introduction into the transformational Sixties. Graphic novelist Bryan Talbot remembers that back in school, ‘I’d read somewhere, probably in New Worlds, that Moorcock had designed Jerry Cornelius to be a sort of template – a protagonist any writer was free to use. I don’t know if this was correct, looking back, but that’s how I understood it at the time, so I based my English assassin, Luther Arkwright, on Jerry Cornelius’. Moorcock has suggested that the roots of his Jerry Cornelius novels could be found in Absurdism.

Because of New Worlds’ progressive nature, with its inclusion of the artistic avant-garde, it did not sit easily within the conservative magazine trade, and the large format newsstand editions of New Worlds eventually folded in 1970. Moorcock later recalled, ‘I think we were all part of a broad movement which was rejecting the played out conventions of Modernism. We were looking for methods which worked for us’. The main problem with New Worlds’ circulation, Moorcock insists, was that Smiths was deliberately blocking sales, having been forced by press disapproval to reinstate the journal following serialisation of Norman Spinrad’s novel Bug Jack Barron. Spinrad’s story, about a video-jock exposing corporate racism and scandal, had fostered complaints because of its strong language. Questions were asked in the Houses of Parliament, leading the distributor to withdraw an issue from circulation.

This era of Moorcock’s career is of particular interest to Hari Kunzru, an admittedly life-long fanboy of Moorcock’s writing. When he met Moorcock a few years ago, Kunzru remembers realising that ‘he was like a one-man cultural crossroads’. Before meeting Moorcock in person, Kunzru went on to say, ‘I didn’t realise the role he’d played in connecting so many different scenes and undergrounds together – the psychedelic music scene, the science fiction scene, the hip experimental literature scene around people like William Burroughs, pop art’.

Contemporary pop artists including the former Independent Group members Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi were featured in the magazine, alongside progressive illustrators such as Pamela Zoline and Malcolm Dean. New Worlds cover images often echoed the work of the IG, a network of artists, architects and critics at the ICA who invented Pop during the early Fifties, long after the IG had broken down. Of the editorial decision, Moorcock explained, ‘It was to make fiction respond to the modern world. We saw science fiction as having the potential to do that – bringing technology, if you like, into literary fiction. We weren’t rejecting modern lit-fic’ but felt current modernism was failing by concentrating only on characters’ inner lives as if those characters were living in the 19th century. The IG seemed to be bringing modern technology and sexual imagery together, symbolised at its best – I always thought – by Paolozzi’s Diana as an Engine’.

Paolozzi, whose often difficult friendship with Moorcock is only now coming to light, had as an insider’s joke served as New Worlds ‘Aeronautics Engineer’ during the end of the Sixties. Of Ballard and Paolozzi, Moorcock remembered, ‘Jimmy and Eduardo got on far better than I much of the time, at least in the early days. But both men were monologists. One of the last times I spent an evening with Eduardo I went with Mike Dempsey to that flat he had at Smith Square. Before we got there we both agreed to talk on an entirely different topic to Eduardo since he was almost certainly [to] talk on a topic entirely different himself. We kept it up as long as we could, with Eduardo droning away as he had come to do, and then broke down into helpless laughter. Eduardo was utterly baffled. After that interruption he carried on as ever.’ During the Seventies, Moorcock eventually fell into the habit of avoiding Paolozzi altogether. ‘Ballard told me he’d done the same. Eduardo had become so pompous and opinionated by then that you didn’t want to be around him. I hid behind an exhibit when I heard his familiar boom at an exhibition. Jimmy told me he did the same at, I think, a movie.’

Moorcock continued, ‘Frankly I would have called Eduardo a misogynist but perhaps no worse than most of the people he grew up with’. In an era of rampant sexism, as demonstrated by his older male peers, young Moorcock joined the US women’s movement and befriended the likes of Kate Millett and Andrea Dworkin, to the chagrin of his elder Ballard. Moorcock remembered, ‘To be honest I have problems with imagery which shows, in my view, aggression towards women and the boysieness (sic) of several of the writers and visual artists set me apart from them so that I didn’t much enjoy socialising with them. I was often called a killjoy because I simply didn’t have any leanings in that direction’.

Known to write some of his earlier novels in two or three days max, Moorcock has divided his time between rural Texas and Paris since 1997. Don’t be fooled by his cover: with his heavy beards and Velcro shoes, he is an adopted Parisian. Currently working on a semi-fictional autobiography, Moorcock happily blames his ‘unreasoning guilt’ and inevitable ‘thousands of ideas’ for motivating him to keep writing after all these years. The majority of Moorcock’s novels are optimistic, with their balance of chaos and order. In an interview with Dworkin, Moorcock asked her to discuss her relentless optimism, which arguably matches his own. The anarcho-feminist replied, ‘Optimism is what you do, how you live. I write, which is a quintessential act of optimism’.

What to pick up first? Miéville made an under-the-radar suggestion. ‘The Black Corridor is an underrated and chilling piece of political pulp modernism that I have never quite been able to parse’, he complemented. Written during the final years of the New Wave, in 1969, The Black Corridor is billed as ‘one man alone in space – fleeing from Earth’ and has a renowned twisted ending guaranteed to perplex. A combined effort with Moorcock’s then-wife Hilary Bailey, amalgamated from his own work and one of her abandoned novels, the pair tell the story of a young Ryan – a possible reincarnation of Jerry, according to Moorcock’s editor John Davey – who is reluctant to take drugs that would halt his rapid descent into madness. This short novel seems more relevant than ever considering the size and scope of today’s Big Pharma. Other tips? Experimental short fiction writer Berry Sizemore recommended, ‘King of the City is one of my favourites. It’s humorous and an eyes-wide-open page turner in a fictionalised London where media moguls fall and the fallen rise.’

When I asked Moorcock what he thought about people who considered science fiction and fantasy to be stuck in a ghetto, he told me, ‘That’s their point of view. I don’t attack or defend by genre but by the author.’ Moorcock already has a massive base of die-hard fans, but we’re betting the reprinting of his novels will inspire a new generation of Moorcock followers.

Michael Moorcock’s back catalogue is being reissued in paperback over the next three years by Gollancz

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more