The Christmas special of Rising Damp is perhaps the cruellest episode of the 1970s sitcom, in terms of just how viscerally lonely it presents Rigsby. It is Boxing Day and he is bemoaning that he has just spent Christmas with only his miserable cat, Vienna, for company. His lustful Scroogelike demeanour suggests he only has himself to blame. He tries to hide when the milkman comes to drop off his order so he doesn’t have to shell out for a Christmas tip and begs the female postal worker to kiss him under the mistletoe. He later makes the xenophobic assumption that his “African prince” lodger Phillip wants to share his girlfriend with him, while the other lodgers take pity and regift him some lavender bath salts.

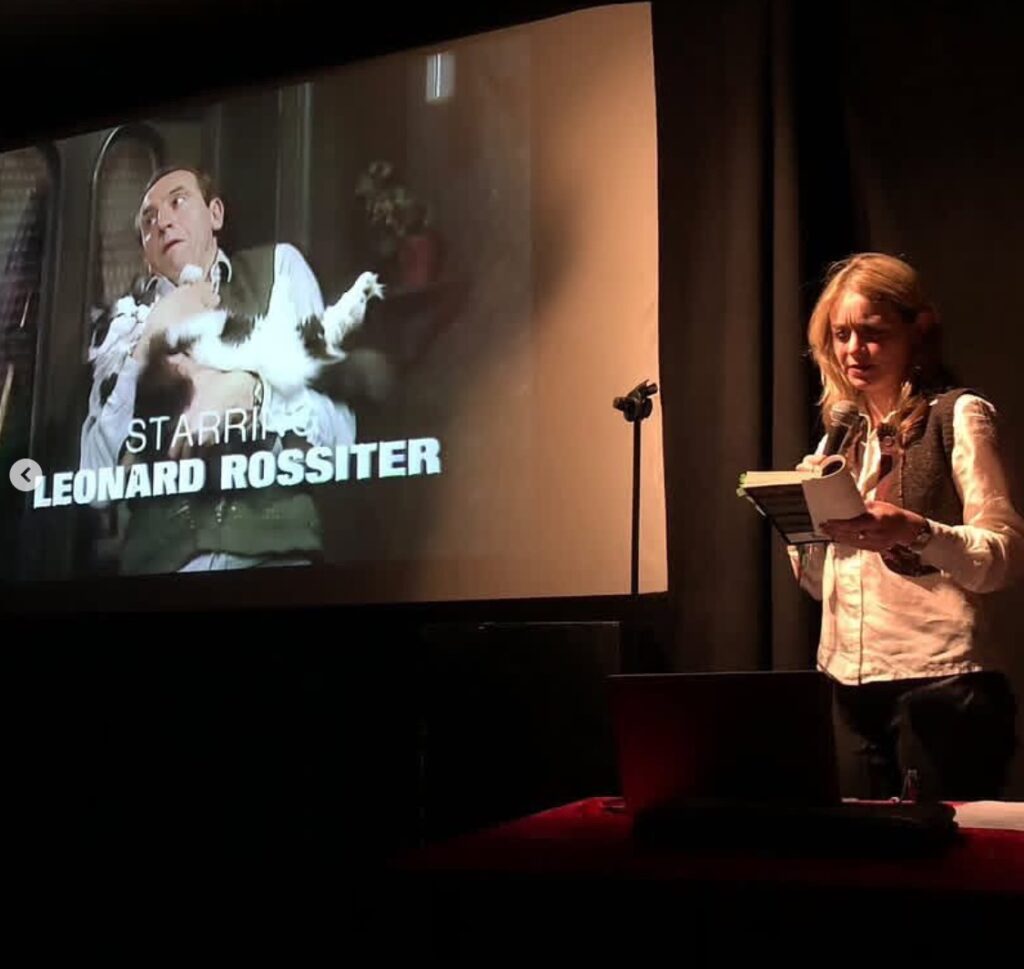

Rigsby was played by Leonard Rossiter, the uncanny (double) hero of Sophie Sleigh-Johnson’s new book, which presents the actor as someone who the wild energy of the 1970s was channelled through, via his roles as hapless rent-counter Rigsby and the existentially bereft executive Reginald Perrin (whose “rise and fall” was charted in the eponymous series written by David Nobbs). Sleigh-Johnson treats these sitcoms as a kind of lost scripture, recasting Rossiter as a high octane ranter. He “talked at double the speed of anyone else”, according to the show’s scriptwriter, Eric Chappell, and “kept the tension throughout each performance” with a torrent of explosive spasms of barely concealed rage and desire. In most scenes, his body, said Chappell, was “bent like a question mark”.

Eric Chappell was born, like Margaret Thatcher, in Grantham, though unlike her he prospered by laughing at the folly of a fervent belief in one’s ability to achieve something worthwhile through the shoddy levers of capital. As Andy Beckett and others have noted, the 1970s were not merely a stagnant experiment in managed decline. The decade is instead summoned by Sleigh-Johnson as a tarnished golden age. It was the highpoint of the sitcom, a time when watching them, she says, “was an appointment kept by millions”. Working-class practitioners such as Chappell and the Canning Town-born Johnny Speight (whose Alf Garnett, based on his racist docker father, became a grim hero to many) read widely and treated the TV sitcom medium as a more immediate genre of theatre.

While it might riff on the hauntological potential of 1970s folk horror, the book’s true darkness lies in what has happened since the Age of Rossiter, when the neoliberalism took hold. “In the world of globalised commerce lies the incipient evidence of what is now dogma: things can be bad, but must be rendered positive in an ego-driven rhetoric of positivity. Comedy has little to do with this enforced positivity, but operates more as a distortion of heterogeneous and personalised environments.”

Code: Damp started as an attempt to create a mythos around Sleigh-Johnson’s different passions. She thought it would be “funny”. Funny is the point here: the hard, guttural, horrific laugh of much of the comedic touchstones the writer refers to in the book, from Bottom to Alan Partridge. It may at first seem wayward in its attendance to the gnostic and the mystic, as if it were fuelled by a psilocybin sensibility. But Sleigh-Johnson’s propulsive prose is aided instead by beer. An obsession with the once fashionable Hamburg-brewed lager Holsten Pils grew out of an affinity with her grandfather drinking it, until it became an aesthetic muse, the logo of the yellow can faintly visible through a polythene off licence bag like a marshland haunting. At some point after a series of filmed performance works and cassette tape releases of experimental noise tracks, Sleigh-Johnson’s life gradually became her work. Her dayjob at the Leigh Times fed into performances, culminating in her making a jacket based on her printed articles. She has collaborated with Paul Buck, a writer and performer whose lineage dates back to the 1960s happenings (and who edited Curtains, which promoted French writers such as Georges Bataille). Her desire during performances often seems a lot like that of the 1970s sitcom writer: to create discomfort. To let a sense of unease just hang in the air. Because, as anyone who watched Rigsby writhe uncomfortably under the mistletoe in 1975 knows, nothing is funnier than discomfort.

Sleigh-Johnson’s mission is the same as Georges Bataille’s, in a sense. She wants to reintegrate the sacred into modern life. The 1970s, according to Code: Damp, was haunted by Bataille’s theory of “the accursed share”, which highlighted modern economies’ obsession with accumulation, creating a “profane” human existence that followed the logic of capitalism and luxury, but ignored the “sacred”, absurdist, animal side of things. This is probably where the damp comes in, and Sleigh-Johnson’s marshland surrealism. In an implicit critique of the rise of domestic influencers such as Mrs Hinch who promote the ideal of the shimmering and sanitised home, the marsh “wasteland” of her hometown of Leigh-on-Sea is instead evoked and connected to the damp of Rigsby’s shambling boarding house. It isn’t thanks to any connection to Rossiter, however, but to the book’s central theory of “damp” representing something of the human, the grotesque, and therefore the funny.

Her prose is at once pared back and meandering, bright yet violently obscure, like a winding marshy sea wall during a dazzling, windswept noon. Occasionally, connections are incanted with such feverishness it can result in bewildering sentences. “Recalling the bivalent vicissitudes of capitalism, such self-knowledge cuts a channel of individuating, whilst atomising the individual in the stream of commercial imperatives. But with the Lutheran reformation onwards, mystical thinking is a synchronic harlequinade that sees the ooze of damp irrigate the soul as individuative process, staining the pulpy everyday with the comedic folk horror of salvation and chip paper.” But stop worrying. This is a book where you simply have to get your head down. Enjoy it the way you would The Fall, another influence, which Sleigh-Johnson makes clear with repeated references and a pointed fragment of lyric from 1984’s ‘No Bulbs’: “They say damp records the past”.

Code: Damp is the most original book Repeater have put out this year, and possibly the most original they have ever put out. If the book reminded me of anything, it was Lipstick Traces by Greil Marcus – if Lipstick Traces had burroweed into the virtues of Time Team and those 1980s Cinzano adverts featuring Rossiter and Joan Collins, and tried to divine exactly what happened between the invention of writing around 3000 BC and the rise of banalised jargon in the twenty-first century. In the same way as Marcus’s 1989 book traced punk back to situationism and Dada, it follows its own logic without blinking. Despite its qualities of mythos and mysticism, it is rooted in the materiality of experience and information gleaned at the archive. It is also unlikely I will read a better set of puns this decade: “Faust and loose”, “Trowel and error”, “bin voyage”. This fixated playfulness drives the book forward, providing a compelling resistance the earnestness that can sometimes derail nonfiction in the 2020s.

A recurring quote in the book is taken from the fourteenth-century Christian work of mysticism written in Middle English, The Cloud of Unknowing: “When you are nowhere physically you are everywhere spiritually.” This is central to the book’s intellectual tension. Code: Damp is indifferent to the importance of place, favouring the frothing incantations of the spirit. Though it was implicitly set in Leeds (in the same way Mike Leigh’s 1970s Play for Today Abigail’s Party was notionally Romford), when Chappell was asked where Rising Damp was set, he replied: “nowhere”.

Code: Damp: An Esoteric Guide to British Sitcoms is published by Repeater Books. The Invention of Essex by Tim Burrows is published by Profile