"If you’re a critic, it is nothing but good to know what it’s like to be on the receiving end of a really stinky review" says Mark Kermode, recently polled as the UK’s most trusted film reviewer and certainly the one with the most reach "Will Self wrote this vitriolic review [of my book] and I think that’s nothing but good. You need to know what that feels like. Danny Dyer’s always going ‘He’s got no idea what it feels like to get a bad review.’ Get your finger out your ear! I know exactly what it’s like, and I still feel exactly the same about bad reviews as I always did. You don’t write reviews worrying if the person you’re writing about is going to feel bad." As he quotes Dyer, Kermode’s voices pitches upwards and cracks ridiculously like a comedy teenager. It’s his signature impression, done with regularity on the BBC 5Live review show he’s presented alongside Simon Mayo for ten years; apparently annoying the B-list cockney muppet Dyer no end. As a critic, Kermode cannot allow himself to care. He has two jobs – to have informed opinions about films, and to convey them entertainingly. Two jobs, incidentally, he’s completely brilliant at.

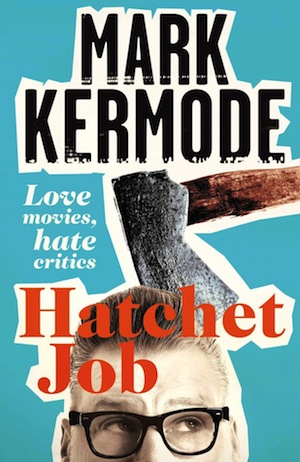

The nature of film criticism has clearly been on Kermode’s mind lately. There was a chapter dedicated to the question "what is a critic for?" in his 2012 book The Good, The Bad and the Multiplex, and the subject is widened out to form the basis of his latest work, Hatchet Job, an examination of the nature of movie criticism and its place in the post-internet, 21st century landscape. It asks the question that has been terrifying professional critics in recent years: in a world that has Amazon customer reviews, instant feedback from twitter and a million amateur blogs what’s the point of paying professional writers?

What becomes clear in the book is that Kermode is as encyclopaedic on film criticism as he is on film itself. He’s a man in love with his art, prone to romanticising the great film critics of the 20th century, especially Roger Ebert, Philip French and the late Alexander Walker, whom Kermode admits to having disagreed with on practically everything. We’re asked if Walker was part of a disappearing breed of highly informed, opinionated broadsheet critics, a highly-knowledgeable eccentric, "always beautifully turned out, with immaculate bouffant hair." One look at Kermode, now lead film critic for the Observer, 5Live, the BBC News Channel, Newsnight Review and The Culture Show, who settles down for our interview in a suit and tie with rockabilly quiff in place (held aloft with Dax ‘Wave & Groom’, quiff fans) and who ricochets from opinion to anecdote to opinion with the confidence of someone who knows they are indisputably correct in all of their views, suggests the age of the critic is far from over.

To borrow your colleague Simon Mayo’s interview technique, let’s start by setting the story of the book

It’s about film criticism, and where film criticism is, in an age where everyone is – in theory – a critic. When I did Radio 4 with Clive Anderson he described it as "worrying out loud", it’s a lovely phrase. I began the book as an exercise in "worrying out loud", because I love being a film critic, I love film criticism, I started writing published film reviews when I was in my early twenties in Manchester at City Limits, frankly I’d love to carry on doing it thank you very much. There was a period that began around 2010 in which an awful lot of very established film critics started to find that their jobs were in danger, if not lost. At the same time there was a rise in twitter quotes on posters in place of reviews. Instead of a critic saying "this film is great" it would be "’Best film I’ve seen this year’ says Sheila from Putney", there were articles saying "has this done away with film criticism?" there were a lot of conferences with people saying "It’s all over".

During the process of writing the book I was much more encouraged, because what’s happened with the internet is that it’s just the latest method of dispersing information. The tools of the trade are the same. I drew great solace from the fact that Roger Ebert was once declared "the end of film criticism", and of course everyone now knows he was a great film critic. President Obama did a lovely tribute to him saying movies wouldn’t be the same without Roger Ebert. As I researched it two things appeared to be true, one is that "this is the end of film criticism" is a death knell that’s been heard over and over, and it isn’t, and second that I love film criticism as a craft and a trade and I wanted to write a book that celebrated it, saying "this is why it’s worthwhile". I wanted to say that as a critic it’s much harder to stand up for something than it is to knock something down.

There’s a nice overlap between your previous book, The Good The Bad and the Multiplex and this one – the last chapter about studios basing their decisions on focus groups, and the chapter in the previous book about "what a critic is for" seem to link the two together – do you think you’ve answered ‘what a critic is for’ now?

What I tried to do, is tell you what a critic isn’t for. Critics are not here to tell you what to see, the theory that criticism exists to tell you how to spend your precious time is baloney of the highest order. Somehow passing your judgment off to a single person or a group and saying "you make the decisions for me?" That’s the most foolish thing I’ve heard. What film critics are there to do is to discuss cinema in a way that is informed, considered and hopefully entertaining. The role of the critic is to do the job properly – to see it as a job, to see it as a craft, and I’m not being hoity toity, it’s like anything else – like being a mechanic or a painter or playing the violin. Just do it, and do it properly – put the hours in. Why is it that Philip French was the greatest film critic in the UK? Well partly it’s because he’s a brilliant writer, but partly it’s because after 50 years he’s seen an awful lot of films. He filed his first review for the Observer 50 years before retiring. By the time he was standing down his knowledge was encyclopedic. Why is it that Kim Newman is consistently head and shoulders above the competition? Because he’s seen so much. And also because he’s a brilliant writer and he’s very funny, he’s got a lovely turn of phrase, but he see’s it as a job. He does it day in and day out, he doesn’t cherry pick what he watches. The role of a film critic is to have seen a lot of films, and to be able to put that film in context with other films, "this alludes to that," "if you like this, you might want to look at that," or "that film that was made before the birth of sound", or "that film you won’t have seen because it was only released in Iran." To contextualise it, then to be able to say accurately "what is it?", then say whether it works on its own terms, then give your opinion about it; and your opinion is only ever your opinion. I write at great length in the book about Alexander Walker – I don’t think I ever agreed with Alex’s opinion, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think he was a great film critic, because he was. It’s not to do with agreeing with opinions and it’s not to do with making peoples choices for them, it’s about talking about film.

What I’ve always liked about your reviews is that, whether I agree with them or not, I always know whether I’d like the film…

If that’s the case then I’m thrilled. I think there’s an equal number of people coming away thinking they have absolutely no idea whether they’ll like it, but hopefully… because one knows who I am, you can always go "well that is an opinion offered by someone who quite seriously thinks The Exorcist is the best movie ever made and that the Richard Gere remake of Breathless is better than À Bout de Souffle" and can then judge those opinions accordingly.

Your next project is going to be a book on soundtracks isn’t it?

I’m writing a book about pop music and movies. I’ve got a probably quite naive affection for films about pop music, but if you look at the history of films, it’s littered with real catastrophes. Great pop music films are few and far between. I’ve developed a real interest in British pop movies, and the kind of pop movies only Britain can make. Only Britain could have made something like Take Me High– "Cliff Richard gets on a barge and invents the ‘Brum Burger’", honestly where else would that happen? Of course when I first started out I had a thing about Slade In Flame being the great British pop movie, and for a while I toured with a 35mm print doing an introduction in which I would say "I know what you all think, but believe me this isn’t the film you think it is", and sometime later I was privileged in that Noddy Holder was very kind about what I’d done for the film, and somebody interviewed Jim Lea in Q or Mojo or something, and he said "when that bloke Kermode kept going on about it I started to think maybe we had done something right", and the thrill of the idea that Jim Lea even knew who I was was indescribable. There’s not a year goes by where I don’t watch that film again. I was trying to figure out, what was it about Slade In Flame? What was it about The Buddy Holly Story that made them great pop movies? Years and years ago I’d worked with the BFI on a book, Celluloid Jukebox, which was a very good book that John Romney co-edited, it’s a series of essays about pop music and movies, which has always been something I was fascinated by. So it’s about movies as opposed to being about pop music, because I’m a film critic first and foremost, but if I get to write about The Rubettes and Never Too Young To Rock then that’s fantastic because it’s got Mud performing ‘Tiger Feet’, and because it’s British they’re performing it at a roadside cafe in the middle of a food fight. There’s a really weird thing about British movies starring British popstars; have you ever seen Gonks Go Beat? It’s got Ginger Baker and space alien puppets. I remember Andy Gill and I, when Celluloid Jukebox was out, were doing some tour talking about the emergence of the British pop movie, and every time we got to Gonks Go Beat Andy would say "no, I’m not making this up, it really exists!" In fact, there’s a clip of it in the recent Ginger Baker movie.

Simon Price recently wrote for The Quietus arguing against Will Self’s review of Hatchet Job, he opened with the Futurist manifesto quote: "regard all art critics as useless and dangerous", does that chime with you?

I think it’s absolutely right that people who make art, and make films should regard critics as "useless and dangerous", but I don’t think thats a reason for not doing it. Film-makers shouldn’t make films for critics, and critics shouldn’t write reviews for film-makers. In an ideal world they would be separated by a gulf. I don’t think film critics should hang around with film makers. I was friends with Ken Russell, and as a result of that I could never look impartially at a Russell film, and anyone who thinks they could – it’s just not true. I loved Ken, and even when he was making his more challenging later work, and if you’ve never seen A Kitten For Hitler…when I look at that film I do so with a beaming smile, having heard Ken tell that story for ten years. He came up with it onstage either with Melvyn Bragg or with Quentin Tarantino, he was having some discussion about censorship. Somebody said "you obviously don’t believe in censorship", and he said "I do believe in censorship", so they said "why?" and he said "you have to have to have boundaries, I’ll come up with an idea for a film that no civilised society would allow to be made", and then as he told the story he fell in love with it, and ended up actually making it. I don’t know what it would be like to look at that film if you didn’t know Ken for ten years and know what was essentially that story. He used to tell it in restaurants and we’d go "no Ken, shhh, not now" and of course, he finally made it. It’s absolutely right that artists should be suspicious of critics and that critics should be suspicious of artists, they’re too different disciplines. That was why I go on at great length about that altercation between Ken Russell and Alexander Walker, I was a very good friend of Ken’s and didn’t know Alexander Walker very well, but there was something absolutely perfect about that collision of worlds on live television, with Ken striking Alex over the head with his copy of the Evening Standard, which as Ken’s producer said was particularly funny because Alex had this bouffant hair cut and he put a dent in it and made it go lopsided. Because I admire both of those people, what I hope comes across in the book is that I really did admire Alexander Walker even though I didn’t agree with him about almost anything.

There’s a quote attributed to Lester Bangs in the film Almost Famous about a good critic being "honest and unmerciful"…

That’s very good. I always remember Alan Jones being a real friend and guide to me, and him telling me very early on when I was on Wardour Street and Dean Street, so excited about the movie industry and interviewing film-makers, "always remember this – film-makers are not your friends", and I now know exactly what he means. And they’re not. And that’s how it should be.

Hatchet Job is out now, published by Picador