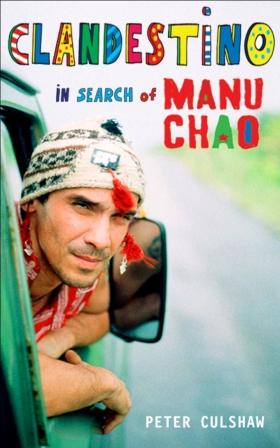

The improbable excellence of Peter Culshaw’s book on Manu Chao not only defies all tenets of rock biography but proves a delight for even the most casual reader, those who have never heard a single song by Chao, know zero about him, "a fish dish perchance?" and previously had no intention of rectifying such ignorance. Considering nothing is more inherently ignominious than the “pop bio”, last refuge of the old-skool hack, final gasp of the few remaining Grub Street irregulars, filthy, battered, eternally untouched at the bottom of every jumble sale cardboard box, Clandestino is a ridiculously literate and rewarding read.

The book has the muscle of a mystery story – part travelogue, part fable, part obligatory biography. Some of such rich adventures with Chao include cancelled gigs due to drug gang outrages in Mexico, a week in a psychiatric unit in Buenos Aires and in a refugee camp in Algeria, not to mention a bunch of proper drinking in numerous bars from Barcelona to Brixton. “A cow saved my life” says Manu at one point, at another “I have met the Devil in person, twice. One of the times he was an Englishman.”

As TS Eliot remarked, "there is no method but to be very intelligent", but when it comes to writing about a contemporary rock star it also helps to actually be able to write, to know how to play the stuff yourself, to have had your own musical career, and indeed to have led as interesting an existence as the subject of your book. For Culshaw seems eminently worthy of his own biographer; a mystic, composer, performer, sometime alchemist and shepherd, who could well claim the title of Britain’s best-traveled man having visited the most obscure corners of the globe in his continual quest for “world music,” an indefatigable adventurer with a taste for not just the middle of nowhere but its final outskirts.

Born some fifty years ago in the county of Leicestershire, Culshaw already distinguished himself as a young man touring the country as the No.2 Chess Champion in the U.K, albeit in the Under-12 bracket, "…and then I discovered girls", a discovery that he has long continued to explore in depth. At Oundle School he launched his first band, a glam-punk outfit which included Michael Morris, founder of the fabled cultural catalysts Artangel, on drums and renowned art dealer Ivor Braka on percussion, whilst fellow schoolmates James Truman of Condé Nast and Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden were turned down as inappropriate. Culshaw, who was already working in the music business booking bands for the school, also had the savvy to be one of the first to hire Queen to come play, at the regal sum of seventy quid for one of their earliest gigs. On another notable occasion he created a ‘Rock & Poetry Weekend’ inviting writer George MacBeth (who was to remain a lifelong friend) as well as painter-poet Adrian Henri, who was scandalously caught by matron in flagrante with his girlfriend, today’s Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy.

At age 17 Culshaw was told by Ted Hughes that he should really study anthropology not literature, advice he avoided for decades until finally taking a masters degree in the subject as a mature-student. Yet whilst at Exeter University he at least launched his next group, The Takeaways, with all the other players being from the local psychiatric hospital, a proto-Surrealist ensemble that counted amongst its groupies the young Iwona Blazwick, now-decorated director of the Whitechapel Gallery. ‘Then I had a brainstorm that I really wanted to be an alchemist and I actually managed to get a grant to do a PhD in alchemical studies, but in the end I moved to the hills of Rutland instead and became a shepherd for a year or so.’

Relinquishing such rural retirement Culshaw moved to London and became part of the still-vibrant underground squatter scene, living for free in a Bloomsbury mansion with seven marble fireplaces whilst regularly visiting the abandoned Cambodian Embassy, grandest and artsiest squat of all, though also notorious for its occult activities. Indeed he himself only just escaped a "psychic assassination" attempt. These were the last great days of boho London, before Thatcherism, before cappuccino-chains, before our standard property mania, the sort of city where someone like Culshaw could attempt an experiment in living without cash, none at all, and could survive for several weeks at a time without a single coin spent, with firewood from skips, food leftover from markets, ‘attempting to prove we could transcend the demon of money.’

In this milieu his friends included sage-squatter Heathcote Williams, St Pancras savant Aidan Dun and filmmaker Derek Jarman, ‘I would go and have tea with him on Charing Cross Road to discuss Jungian psychiatry and dream-theory.’ On Culshaw’s very first weekend in London he had been taken to meet playwright Ken Campbell and then spent 24-sleepless-hours performing in that psychedelic classic of the era, and still the world’s longest play, The Warp.

In keeping with such radical energies Culshaw soon found himself editor of Undercurrents, the world’s first alternative technology publication then at the height of its success, and oft quoted as an important influence by pioneering Green politician Petra Kelly. This was followed by a stint setting up another more mainstream eco-magazine entitled Tomorrow, created and funded by Katherine Hammett at the height of her political-slogan T shirt fame, whilst as a budding journalist he himself regularly banged out columns for such modish glossies of the time as Blitz and The Face.

Going on to establish himself as one of Britain’s leading writers on global-beat world-blah-blah Culshaw began to travel continuously on assignment for every sort of organ, not least helping to bankrupt The Observer‘s music magazine with the most expensive article ever published in that paper’s history, an exhaustive investigation of the life and music of Congolese Pygmies. ‘When you bribe people they don’t usually give you a receipt’ he briskly explained to the paper’s managing editor when he queried Culshaw’s eye-watering expenses.

Indeed it would be easier to specify a country and publication that Culshaw has not visited or worked for, perhaps Luxembourg and The Lady, than to try and list his endless peregrinations and deadlines, suffice to say that he has not only been everywhere, usually twice, but also specializes in wildly ambitious itineraries, thinking nothing of taking the Belize-Buenos Aires-Korea shuttle, followed by a double-whammy Bombay to Trinidad long-haul. Continually “just back” from somewhere Culshaw tends to leave again almost simultaneously, his basement in Stoke Newington serving as a one-man Heathrow pit stop. It’s an exhaustive and exhausting travelogue that has included making art with Joseph Beuys in Edinburgh, smoking kif with Paul Bowles in Tangiers, sampling the ‘Dream Machine’ with Brion Gysin in Paris, staying in the Sahara with desert rock heroes Tinariwen or jiving with the Nigerian pop star Fela Kuti, his many wives and “personal magician” Professor Hindu.

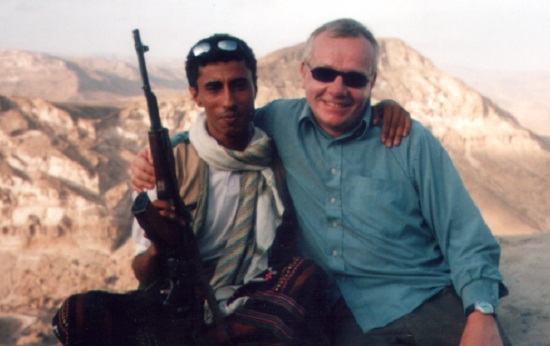

‘I was out drinking with this brilliant classical pianist Boris Beresovsky in a Siberian casino,’ is classic Culshaw but said without the faintest trace of boast nor bombast, rather with a rueful self-deprecating stoop ‘fortunately I was found asleep in a snow drift at 3AM, surely the closest I came to dying.’ Closer even than such close shaves as being shot in the backstreets of Havana or running foul of a Jihadist warlord in the Yemen.

Culshaw’s own musical career has long run in tandem with his work writing about others, beginning with ‘Dark Breakfast’, a show he mounted with a Dutch choreographer at The Place in 1982, followed by The Young Pioneers a conceptual-Communist combo who headlined the ICA in 1986. With his group The West India Company Culshaw gained a commission to create a score, ‘New Demons’, for the renowned dance company La La La Human Steps, and where on attending the world premiere at Sadler’s Wells Culshaw’s parents were seated between Davids Byrne and Bowie. This band were signed to Brian Eno’s label Editions EG and soon found themselves based in Mumbai, engaged in a vastly ambitious recording project with Asha Bhosle, India’s most famous singer, and Boy George, then one of Britain’s dittoes. Vast amounts of money were spent, local gangsters threatened, and mad schemes hatched, including an opening performance at the Taj Mahal, with the lighting-designers for Pink Floyd and eighty-foot inflatable elephant Gods, though finally the album Real Love sank into a mire of law-suits. Meanwhile Culshaw had been hatching plots with his next door neighbour the director Shekhar Kapur, a film treatment that later ended up, curiously enough without the name Culshaw in any way attached, as the long-running musical Bombay Dreams.

Undaunted, Culshaw next launched the album New Hope for the Dead on the JVC label, whilst also creating a Cuban musical, recorded in Havana with the musicians from the Buena Vista Social Club, many of whom he had known and worked with long before their celebrity. And as a Cuban regular, who was always invited for drinks by Castro at the Palace of the Revolution during the Havana Film Festival, whilst hanging out with the likes of Helmut Newton, Oliver Stone and Gabriel García Márquez, Culshaw managed recently to get the great musician Juan de Marcos González to cover two of the potential hit songs from this long-planned musical.

As well as creating his own music Culshaw has been, hah, instrumental in promoting the work of others, whether putting out compilations such as Sampa Nova, a selection of Sao Paulo whizz-kids or helping organize the annual ‘Music Village’ festival, traveling himself to recruit acts from Morocco, Pakistan and South Africa, where he so predictably met with Nelson Mandela. He also acted as de facto agent for Brazilian band CSS ‘Tired of being Sexy’ whom he personally discovered playing to handful of drinkers in a doomed Sao Paulo bar.

Perhaps hardly surprisingly considering this practical involvement in the music biz, one of Culshaw’s closest friends was the late Malcolm McLaren, who happily used to give him guided tours of his jeunesse around Stoke Newington, and would end up sleeping on his floor in said borough. Indeed Culshaw even worked hard as Campaign Manager for McLaren’s attempt to become Mayor of London in 2000, initially up against Frank Dobson and Lord Archer. This splendid political folly, all paid for by Alan McGee, actually managed to get up to 18% in the polls, despite, or perhaps because of, their promise to provide alcohol in all public libraries and open a legal brothel outside the Houses of Parliament.

With McLaren he lived some of his grandest adventures, hanging out at the Playboy Mansion as the LA riots rioted all around them, or celebrating the Millennium at the chateau of fashion-designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, toasting the new century with quite literally the finest wines in all the world. Not for nothing did Malcy leave Culshaw his car, a 1984 Mercedes that he had to personally go and collect in Paris and drive back to Stokey, that vintage vehicle boasting ‘an amazing sound system, great CDs and piles of unmade film scripts in the boot.’

Yet Culshaw has somehow managed to guard his fundamental mystique and elusive aura, that Scarlet Pimpernel of Worldbeat, despite the threat of his first book’s current cult status actually blossoming into mainstream bestseller success, what with lines of fans awaiting the flourish of his signature at Latitude and foreign rights snapped up everywhere from Finland to Bulgaria. Just back from the Fez Sacred Music Festival, which he’s graced more than fifteen times since its founding, Culshaw is busy plotting a season of new Indian electronica in London and Mumbai, a TV documentary about water and a “metaphysical memoir”. He’s also working on a new piece of “medieval tantric disco” to be premiered in October, being interviewed for sundry BBC documentaries, and battling a steady stream of international fan mail, though as he’ll readily admit with a suitably world-weary sigh, ‘It’s all wrong somehow, I was always supposed to be a famous Sufi.’

Clandestino In Search of Manu Chao is out now, published by Serpent’s Tail