Luna Miguel has only one collection of her work available in English, Bluebird and Other Tattoos (we need more!), a selection of poems drawn from several of her Spanish works which include Estar enfermo (2010), Poetry is not dead (2010) and La tumba del mariner (2013). Born in 1990 in Madrid, she published her first book – written between the ages of 15 and 17 – at nineteen, and to date has five original collections of poetry to her name. Her work has become known to English speakers via her online presence, her involvement with the Alt Lit ‘movement’ (if that is even the appropriate term) and translations of her poems available on sites such as Electric Cereal, Shabby Doll House, New Wave Vomit and Adult Magazine (not to mention this site, dear reader).

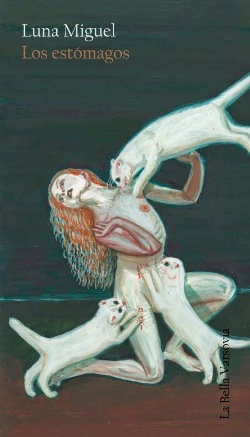

Luna writes poems that are fierce, tender, gutsy – by which I mean ‘brave’ but also literally gutsy (her latest collection is called Los Estómagos, The Stomachs): she is a poet who addresses the body in all its gruesomeness and glory. In ‘Bad Blood’ she writes: ‘The world, outside the capitol, was an enormous hospital with uteri and rope, and pancreases hanging from doors…and pus, Panero’s poem secreted like pus’ (we need more poems about pus!) and ‘Too bloody? Blood is the nectar of poets. All blood is worthy of a poem. All that menstruates is worthy of a poem’.

I spoke to Luna (via a translation by Luis Silva) about her writing and about bodies, Alt Lit, mermaids, tattoos, the living and the dead.

My first introduction to your work was seeing you read your long poem ‘Museum of Cancers’ at the Serpentine 89plus Marathon in 2013. I don’t speak Spanish but your reading was so powerful it didn’t matter – it was like listening to an incantation and I fell under its spell. Is the physical act of reading your work aloud important to you?

Luna Miguel: Poetry for me has always had something corporeal about it. If I write, it’s because I feel the impulse to write. Because my body needs to write, it needs to write about itself, and thus display itself to others. I appreciate your kind words about my reading a few years ago in London. The truth is that I was comfortable and at the same time nervous. Everyone there spoke English, a language that I can’t surround myself in easily except when I am reading alone. Going on stage and reading a poem in Spanish was perhaps strange for those around me, but the truth is that I felt a warmth from the audience. ‘Museum of Cancers’ is a poem that needs that warmth to exist. My poetry, in general, needs that warmth. That’s why I need the viscera, the love, and the sense of enchantment you spoke of to be present in my poems. It’s a way of stripping oneself naked, and in doing so, laying the world bare.

You write a lot about the body – the body in pain, in crisis. In one poem you write: ‘from poetry i hope evil / i demand disgust / i invoke disease’. In ‘Father’ you write about a couple trying and failing to conceive (‘father pounds his dick into the sick vagina’); your new book is called Los Estómagos (The Stomachs). In our society it feels like there is always shame attached to bodies, particularly ‘failing’ ones. These poems feel like they refuse shame by putting it on display. Can poetry ever make it easier to live inside a body?

LM: Exactly. This is what I was referring to before. The poetry that interests me the most is the type that is born from the visceral, that’s why one of my favourite poets is the surrealist Joyce Mansour and why my favourite poems by Ted Hughes are those in which the spotless well-mannered poet is able to stain his hands with blood and life. A good literary text, in my opinion, is one that moves bodies, that provokes reactions. That’s why I’m so obsessed with this duality, and that’s why in my own poetry I intend to make skin, organs, bones, and emotions visible. In this respect, I’ve learned a lot from Chantal Maillard, Nichita Stanescu, René Char, Alejandra Pizarnik, and Diane di Prima who has just been translated into Spanish and whose book Loba represents the type of poetry I always feel the need to read.

I read some of your more recent poems, such as ‘Mermaid’s Reef’, as being poems of mourning, and I’ve really appreciated this work – these are topics (for obvious reasons) not so often touched on by younger writers. Is writing poetry cathartic, or is that a false notion?

LM: Here we come to the subject of the body again, Emily. In truth I don’t want to talk about death, but in the last few years death has come into my home and taken people I love. ‘Mermaid’s Reef’ is a kind of prologue to the book I’m writing (it’s also titled Mermaid’s Reef), and I hope it will be a close to the latest chapter in my work and in my life which has been marked with so much illness and death. I’d like to write now of happiness and celebration. I’m sick of sadness. I think it’s time to push her off my path. Hopefully I’ll accomplish that…because, as you said, when writing about such difficult subjects catharsis is often a false notion. No matter how much I write, no one can ever give me back what I’ve lost. Although there is a quote by Reinaldo Arenas that comes to mind: ‘We have no oceans left, but we have the voices to invent them.’

Tell me about your involvement with Alt Lit. How has this impacted on your work, either in terms of the actual writing or in opportunities, friendships etc?

LM: I began reading Tao Lin when I was fifteen. At that time, around 2006, I don’t think the term Alt Lit existed, and if it did, I didn’t read about it until years later. The thing that interested me about Tao was his newness and his distinct way of understanding literature. Back then I was living in Nice, France, where I was studying in a fairly strict literary programme that had a curriculum full of classic French literature. The truth is that combining the literary life of the internet with my studies was both healthy and entertaining. What did Victor Hugo have in common with that American poet blogging on my laptop screen? Everything and nothing. And that was beautiful. To me, that’s Alt Lit: emotion, youth, support, politics, viscerality, humour, autobiography, the future, a joke on mainstream publishing, a new way of communicating, and above all else friendship. It’s curious how despite all these scandals around misogyny and the issues and jealousies that have arisen among the Alt Lit writers, what remains for everyone is the most important: the literature. Distinct, brutal, and heroic voices are what remain at the head of all this.

In Latin America, there is a space for a similar type of communication, very much influenced by Alt Lit, it’s called ‘Los Perros Romanticos’. It’s a Facebook group lead by Didier Andrés Castro and Kevin Castro that serves as space for young writers from Peru, Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Spain, Venezuela, and Ecuador to discuss poetry and a thousand other things. I believe that the most important thing about Alt Lit and Los Perros Romanticos or whatever term used is that they serve as spaces for young voices to feel supported, in a world in which new ideas are usually not accepted. And to answer your question (after my rant, sorry!), for me personally these spaces have given me life, confidence, and the certainty that not all is lost. The word is alive, and I’ll never be alone in believing that.

If being part of a community of writers is important, do you also claim the identity of ‘writer’ or ‘poet’ and if so what does it mean to you? You often reference other writers (living and dead) in your poems.

LM: This is something I’ve often done in my poetry and in my blog. I think it’s a show of gratitude. To write we need to read, so I try to read a lot. Sometimes I’m inspired more by what I read than my own life and it’s necessary for me to acknowledge the writers who have inspired me. So that’s why I talk about them so much in my poems. In Los estómagos, for example, quotes by Hughes and Plath show up a lot because I spent almost a year of my life reading them and reading about them, until I felt as if I knew them better than my own parents. To sum up: yes, poetry is corporeal, poetry is necessarily personal. That’s why I need names, people, poets, and quotes surrounding me at all times.

Where do your poems come from? I mean, when you start writing a poem, what is that experience like? Do you have any particular, reliable ‘inspirations’?

LM: Like I said before, to write I need to read. Without other poets I couldn’t be a poet myself. I’m often stuck in silence until suddenly a book wakes up all the connections in my brain and then everything I’ve been holding inside starts to shine and that pushes me to sit down and write and write and write. I like to begin writing in my notebook and then on my computer. I need to listen to music and I need to read it aloud over and over again. Sometimes I write a lot, for months at a time. Other times I can’t write a word. Now, for example, I feel blocked. I’m waiting attentively for my moment to say everything that I know I need to say to myself and to all of you. When that moment arrives, it’s (pardon the comparison) like coming. Finally you reach that sensation of speed and creativity that you’ve waited for for so long.

“Despite all these scandals around misogyny and the issues and jealousies that have arisen among the Alt Lit writers, what remains for everyone is the most important: the literature.”

Bluebird and Other Tattoos is the only collection of your work currently available in English. You have written: ‘Tattooing ourselves is unnecessary. Why record on our skin what is already inside us. Why record those words if we don’t know them already by memory.’ Is poetry also unnecessary?

LM: Like poetry, the world of tattoos is an obsession of mine. My latest tattoo was done by Letizia Ruggirello on February 2015 and it’s a line by the young Mexican poet Jesús Carmona Robles: ‘the poem bleeds’. I don’t want to return to the subject of body-poetry or I’ll start seeming like a bore (hehe), but I think there is a connection between these two things. Describing one’s skin is as necessary and unnecessary as tattooing it. In the end, both things are inerasible marks on our lives and on the world. I couldn’t live without them.

I know you have a ‘mermaid tumblr’ and a mermaid tattoo…Tell me more about mermaids.

LM: Although I’ve sort of abandoned this tumblr recently, I’d like to continue it soon. Like I said before, I’ve been writing my next book since May 2014, Mermaid’s Reef. I live in Barcelona, was born in Madrid, but for most of my life I lived in the south of Spain, in a small marine city, Almería. There is a place there that is very special to me, it’s called the Mermaid’s Reef. It’s next to a lighthouse. It’s a rocky area where it was once believed mermaids swam. Close by there is a small beach where last year my father and I spread my mother’s ashes. We call it Little Carthage, because she was a historian and a fanatic of the Phoenician city.

When I saw my father head into the waves to let go of the ashes, I thought my mother would transform into a mermaid. That’s why I tattooed her on my arm as a mermaid, strategically in my arm, a place where no matter what happens I can always look to her, hug her, and kiss her face. Since then I’ve been obsessed with mermaids, and I’ve sought to read everything I can about them, even if the book I’m writing has little to do with myth.

What else can I tell you about mermaids that you don’t already know, Emily. I think they are such strange and beautiful symbols, whose form and meaning has changed throughout time and literature. Today I want to think of them as voices of the past, who help the rest of us to face the future.

Your more recent poems seem to be longer, more prose-like than earlier ones (some of which are very short or, if long, have short lines) – is this change something you were conscious of? I suppose I mean: what is your relationship with form?

LM: I believe that I need more space to say what I want now. I’ve also been influenced recently by reading Latin American poets like David Meza, Raúl Zurita, Roberto Bolaño, Vicente Huidobro, Mario Santiago Papasquiaro…whose works are long, extensive, and torrential. There’s a big difference between the literature written in Spain and the type found in Latin America.

After reading so much European and Anglo-Saxon literature, I’m trying to immerse myself in a culture that is much closer to my own, and was perhaps less accessible, until now, thanks to the internet. But like I said, the length is a thing of pure necessity. If I write longer works it’s because my voice needs to extend itself a little more.

You also work as a journalist – how do you move between journalism and poetry? Do they complement each other or do you need to make a separate space for each?

LM: I’ve been working for PlayGround Magazine for a while, and I’ve collaborated with various publications in Spain and Latin America (S Moda, Nylon Español, Tierra Adentro, Jot Down…). If before I said that to write poetry I need to read, I would also add that to be a writer I need to write about other writers. I’m really interested in mixing my passions and taking them to the extreme. That’s why it seems like the creative urge that leads me to write certain articles is the same as the creative process of writing a poem, with the exception that one makes me a living and the other doesn’t. I’ve been sick for a few days, and I’ve missed working. I believe writing is a necessity, whatever type of writing it is. I need it.

What are you reading at the moment?

LM: I just finished Eve Ensler’s incredible memoir, which has recently been translated into Spanish. I’ve also read a comic about maternity by Agustina Guerrero, and I’m in the middle of a few poetry books like Fantasy by Ben Fama, it by Inger Christensen, Do What I Ask of You by Miriam Reyes.

I know you’ve read in London and in New York (and presumably elsewhere?). Which other Spanish poets should we (English speakers) be reading?

LM: I say it as a joke but it’s true: poetry is my travel agency. Since 2009, I’ve done readings in Russia, Morocco, Romania, Mexico, Belgium, and the cities you’ve mentioned. I consider myself very very very fortunate that festival organisers and heads of foreign art centres have asked to work with me. In all these places I have made many friends, especially in Romania and Mexico, where the people are humble, marvellous, and hopeful. I would like to continue travelling but my job doesn’t always permit it. I’ve never learned so much in my life than when I travel. And I must say again: I’m very fortunate.

Among my colleagues, I think there are amazing voices in Spain. If I focus on the youngest, I would say Elena Medel, Berta García Faet, Unai Velasco, Layla Martínez, Arturo Sánchez, and Óscar García Sierra are my favourites. If we extend our focus, I’d say I would not be able to understand poetry without José Ángel Valente, Chantal Maillard, Maite Dono, Juan Carlos Mestre, or Julieta Valero. For classic writers, Vincente Aleixandre is my favourite.

In one of the poems in Bluebird you say ‘I will end up doing anything but poetry’…so, what are your future plans?

LM: Journalism, cultural management, editing, life, motherhood, travel, reading…but I can’t lie…poetry will always be there.

Los Estómagos is out now in Spanish, published by La Bella Varsovia

Emily Berry‘s debut collection of poems Dear Boy (Faber & Faber, 2013) won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection and the Hawthornden Prize. She is a contributor to The Breakfast Bible (Bloomsbury, 2013), a compendium of breakfasts. www.emilyberry.co.uk