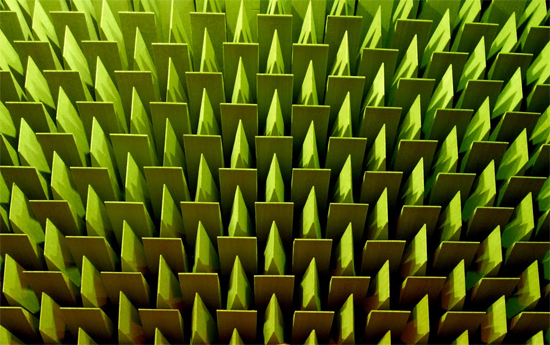

Main image: detail of anechoic chamber wall

Evie Steppman, narrator of The Echo Chamber, is born – so she claims – with remarkable powers of hearing. Evie is a child of Empire (her father is a British colonial officer in 1950s Nigeria), and so the source of her vast internal archive of sounds is Lagos, her native city. In the following extract, Evie

describes how she first learns to harness and develop her powers of ‘listening’ as a ten-year-old during daily trips to the market with her friend and carer, Iffe, an onion trader.

How I Developed My Powers of Listening

It started with the sound of rain. One afternoon, pressing my ear against the underside of the onion table, I drew back sharply, for the vibrations thundered in my head; how violently the rain drummed on that hard surface! After that I began to listen into or within its grain, and soon I started to pick out its

individual elements. I noted, for instance, the hissing as it fell through the elephant grass, and the slap and thud as it beat off roads, sounding like a team of barefoot runners sprinting over wet sand; also the high percussive noise as drops bounced off pots and pans; and when it passed through plants and foliage, the noise was more like a continuous sigh; which I set apart from

the drops filtering through trees; or the brighter pop and loose tripping of the water falling and flowing in the gutter; or the violent clatter on corrugated iron, which sounded like prisoners banging tin cups against the bars of their cells.

Sitting beneath the onion table, I found I was able to isolate the individual tones, set them apart and, as it were, spread them before me. That is when I understood that raindrops themselves are silent, and in falling carry only the possibility of sound, just as the hammers of a piano, waiting silently above the strings until the pianist begins to play, hold in their

matter a kind of latent music… except that the piano has a limited number of strings; but the rain – there was nothing on which it did not choose to drum!

Each body on to which the droplets fell gave off its individual hum or resonance. I wondered what the rain might sound like if I was under the sea, or in a canyon, or on a cricket field, or else flying in an aeroplane. My favourite sound was also the hardest to make out: it was the hollow plash as the rain fell into puddles and the shallows and deeper waters of the lagoon.

And it was this same sense of delight in charting the hidden sounds of Lagos that coursed through me even after the wet season ended. The afternoon the rain stopped I recall the earth’s sighs, accompanied by sheer blue light. Colour returned to Lagos, and Jankara market became bright with sound. As for myself, I remained quiet. Apart from the odd insect, I was rarely

disturbed. At lunch Iffe continued to bring me soup, and every now and then she glanced down to make sure I was still there.

Fortunately, I did not want company. I was happy to be alone, for I had discovered the most resonant spot, slightly to the right of the table’s centre, squeezed between a pair of onion baskets. There I sat, cross-legged with my hands on my knees, my head cocked to the right, growing ever more solitary and reserved. Above me birds chattered. I made no noise. The sun shone

fiercely. I closed my eyes to the sun. Nothing mattered to me so much as listening. The sounds arrived in torrents.

I developed a ritual to prepare myself to receive the city’s sounds: on arriving at the market I would stand in the street, stretch my arms out and begin to spin, faster and faster, until the noise of Lagos rose up in a kind of liquid swell; then I would tumble beneath the onion stand and close my eyes; with the city still lurching, I would take deep breaths until my head began to clear; and, as the sounds composed themselves, I would begin to pick out each individual tone and timbre.

I heard corridors of cloth flapping in the textile section, the snap-snap of barbers’ scissors, the awful sucking sound of the snail woman scooping snails from their shells, as well as the rattle of lizards circling their cages, also the furious buzzing of flies at the meat section, and the breathing – slow, heavy,

guttural and irregular – of the homeless men on Broad Street. I listened to the footsteps of the delivery men: the tomato man had a heavy walk; the orange man walked with a limp and drew a wonky cart; as for the onion man, who was not a man but in fact a boy, he had a light tread, as of water trickling down steps, and he whistled Highlife tunes. Without moving, I liked to follow

him on his rounds, up and down the onion line, and later, after his work was done, I would follow him to the north quarter of the market, where he visited the barber or scrounged palm wine and played cards.

Soon I had so thoroughly listened to Jankara market that, without stirring from my resonant cave, I could ‘roam’ the district, explore its every shack and alley, simply by picking out and following particular sources of sound. I began to expand my territory, first eastwards to Ikoyi, where I noted the wind fluting along the electricity wires, and the creaking of the weather vane on St Saviour’s Church, and the whirr of bicycle wheels, and bells, and radios playing different kinds of music.

Next I listened to the Brazilian quarter, with its narrow lanes of booming traffic, its thousand boisterous horns, and also the squeaking of a wheelbarrow. I heard hammering and sawing much building work was taking place. I was drawn to one structure in particular, St Paul’s Breadfruit Church on Broad Street; there every sound reflected off the cavernous walls, doubling, splitting, colliding, crashing. I was learning to make out the

distinctive echoes of certain spaces. Next I travelled west, past Tinubu Square with its hissing waterfall, past the shore of the lagoon, where I noted the sounds of that day’s catch, flapping and dying. After that, I travelled all over Lagos, listening to each district, each corner, each backyard and blind alley.

Meanwhile, the life of the market continued, unaware of the miracles happening between my ears. I was no longer a novelty for the traders, but merely strange, an oyinbo child sitting with closed eyes, saying nothing, needing nothing. Sometimes they brought their faces close to mine. I remember a large sweaty face with shining eyes asking, ‘Wassamatter?’ It was a tomato seller. She had became suspicious and suggested I was eavesdropping in order to tell my father about their plans to ‘sit on a man’.

(But she was mistaken; in this period I rarely listened for meaning; only raw sounds interested me, and if I heard the traders discussing their plan to sit on a man I was only dimly aware of the meaning of their words.) Mostly, however, the traders considered me harmless, a bored, solemn, remote little

girl.

Had they observed me carefully, however, they might have seen signs of the complicated workings taking place inside my head. My ears, for instance… were they not a little too large in proportion to the rest of my features? And did I not feel them quiver, ever so slightly, as I struggled to hear the widest spectrum of sounds? I cannot be sure. What is certain is this:

that while events took their course above the onion table; while Nigerian statesmen called for self-government with increasing stridency; and my father continued to bury himself in his work at the Executive Board; while Iffe and the market leadership travelled to Government House to protest the slum clearances – while all this was going on in the world beyond the onion table,

beneath it marvels were taking place.

Was it here, where I sat, that there existed a special property of sound? Had I chanced upon the city’s acoustical hub, towards which all sounds were inexorably drawn, as in some cathedrals there exists a nook, designed by the architect, where one can hear the tiniest whisper? Or was I myself that hub? Perhaps, I thought, I was like the radio, which could gather sound waves from all over the world. Yes, from all over the city the sounds rushed to me, as if I, who until now had left their paths unchanged, had started to emit some principle of infinite attraction.

And yet, I thought, I was not exactly like the radio; I seemed to attract sounds, but I did not broadcast them, something I had no desire to do. What happened to a radio when it was turned off? I asked myself. I thought about this for a long time. What does a radio do with all the sounds when it is asleep? Perhaps it trembles internally, I thought. Perhaps its insides stir with

the trapped energy of untransmitted sound. Yes, I thought, the radio must exist in a kind of tormented state when it is switched off, hounded by an internal din, like the drunks who wander the streets, arguing with invisible enemies.

It was at that point that I began to question my powers of listening. I began to feel that the richness of my audile faculties was a danger to me. Where did all these sounds go? I felt my insides quivering. The glittering noises of Lagos which came surging towards me, arriving at first in what had seemed like a necessary sequence, began to confuse me. Soon I was unable

to decipher or name the individual tones. In time I even found I couldn’t think properly. I mean I was unable to entertain ideas or sustain notions of a general sort. For instance, it became difficult for me to comprehend the word ‘footstep’. I could not understand how one word was able to embrace so many unique treads, and it pained me that a footstep heard at midday on the

market’s gravel path should have the same name as the footstep heard at one o’clock on the asphalt pavement over Maloney Bridge. My own footsteps, my own voice, surprised me. I wanted to capture all these sounds, but I was condemned to listen to fragments.

In an attempt to contain the din in my head, I composed a catalogue of sounds. Now, all these years later, trying to recover this catalogue, I am plagued by doubts. I fear that, by committing it to writing, I will deaden what existed entirely in my head: the constantly shifting association of sounds.

Displayed on my computer, my order will seem no order at all but an ugly, arbitrary act of preservation. What is more, it strikes me that the very act of preservation – the translation of sounds in my head to words on the page – signals the destruction of the very sounds I wish to save, just as for Linnaeus the only true subjects for contemplation were the specimens he collected and

put to death, stifling life even as he tried to preserve it.

Nevertheless, I will transcribe my Universal Catalogue of

Sounds (Lagos):

a) Sounds that come from me

b) Sounds that seem to rise from underground

c) Sounds that mimic other sounds

d) Sounds that I have never heard but which I will, one day

e) The sound that surrounds two people who’d like to speak but cannot

f) Sounds that only others can hear

g) Unearthly sounds

h) Sea-sounds

i) Sounds that cause my heart to beat faster

j) Sounds that have just caused a traffic accident

k) Sounds that seem commonplace but which become impressive when

imitated by the human voice

l) Sounds that arouse a fond memory of the past

m) Wet-season sounds

n) Silence

o) Sounds that lose something each time they are repeated

p) Sounds that can be heard only in the month of January

q) Sounds that indicate the passage of time

r) Sounds that fall from the sky

s) Sounds that gain by being repeated

t) Insignificant sounds that become important on particular occasions

u) Outstandingly splendid sounds

v) Sounds that should only be heard by fi relight

w) Sounds which I deliberately make, but which are not words

x) Sounds that come from inside me, involuntarily

y) Sounds with frightening names

z) Sounds that cannot be compared

Review of The Echo Chamber by Luke Williams, published by Hamish Hamilton

The narrator of Luke Williams’ epic debut novel, Evie Steppman, is holed up in an Edinburgh attic, writing against time. Born 54 years previously with what she believes to be superhuman powers of listening, Evie’s memories are rooted in the aural. But she’s going deaf. Her memory is failing along with her hearing and Evie must write her story before the sonic archive that is her past disintegrates into a howl of feedback. Through Evie, Williams

has set himself the task of writing a Proustian paen to sound and its Beckettian shadow, silence. Specifically, the silence Evie begins to crave through narrative exhaustion after her

digressional, expansive and bewitching history takes us from the Old Testament to pre-war Oxford to colonial Nigeria. Evie’s own story, or ‘history’, is cluttered with other stories that,

Perec-style, are prompted by the material traces of her past – the objects which surround Evie in her attic.

These stories circulate around Evie’s childhood in Lagos, during the last years of British rule in Nigeria. Ostensibly, this period of history is The Echo Chamber’s subject, although

the book’s ambitions extend far beyond the analysis of a specific historical moment. Williams is examining the idea of ‘history’ itself, of the fictitious nature of any such attempt at a definitive narrative. Buried within the novel are eye-witness accounts of massacres seemingly garnered direct from historical sources, alongside life-like portraits of mythic historical personages and even the diary kept by a member of David Bowie’s entourage on his 1972 US tour — which wasn’t even written by Williams, but by another writer, Natasha Soobramanien, as the acknowledgements later inform us. All and nothing is fiction, it

would seem. Evie’s grandiose use of the word ‘history’ to describe her memoirs serves as a frequent, ironic reminder that Williams’ book is in fact an imagined micronarrative, sitting in

opposition to totalising historical metanarratives. We get a child’s-eye perspective on the fall of the British Empire, from a delusional girl whose oversized ears have led her to think that

she can hear things which no-one else can. The premise offers Williams tremendous scope for invention: Evie believes she can remember stories heard in the womb, those her father

read aloud to his as yet unborn child; and as a six-year old she is able to take the reader on a remarkable auditory tour of the streets of Lagos without ever leaving her spot under a stall

in the marketplace. Her memories of a period spent living in the pits of the Lagos night-soil workers read at once like experiences utterly real and lived and yet also as though they may be the product of a fever brought on by some childhood illness.

A classic, unreliable narrator, Evie’s unreliability is nevertheless extremely captivating. Her obsession with sound offers a rich point of focus for Williams’ lyrical, sumptuously

descriptive prose. The novel itself takes on the form of a collection of lost sounds much like the one Evie attempts to assemble with an old tape recorder in the latter part of the story. For all her enchantment with the auditory world, however, it is a desire for silence – and to become silent herself – which drives Evie. She wishes to finish her history and escape from

her past. But she is aware that her dream of silence is unattainable, for she has visited an anechoic chamber, in which she was horrified to discover (as John Cage did) that she could

still hear the functioning of her own body. Her horror finds its only antidote in activity: Evie sets about transcribing other texts in order to escape her own words; through immersion in

the writings of others, she hopes she will no longer notice the sound of herself.

A novel of vast scope and ambition, The Echo Chamber is a magnificent achievement, quite staggering for a debut novel. It brings into focus the relevance of the past to our present-day

world. As a written document of sound it is exquisitely beautiful. It echoes long in the mind after you have put it down.

Author Q&A

Given that The Echo Chamber is so focused on the sonic, how helpful was listening to experimental/avant-garde music in writing this book?

Luke Williams: Extremely useful. Though at first I spent more time reading about experimental music and sound art than I did listening to it: Evie’s project is to transcribe her largely

auditory memories into language, so my research focused on written works which dealt with sound. I found Douglas Khan’s Wireless Imagination particularly useful. But when I hit a period of writer’s block and stopped writing altogether for a while

I actually got seriously into listening to it. I’d become disillusioned with the writing process, or rather, with Evie’s ambition to try to capture sounds in words, and had got myself stuck. I kind of lost faith in language. Reading lots of Beckett was a comfort, though hardly helped. But listening to people like Schnittke, Pierre Schaeffer, Clara Rockmore seemed to make sense. It was music that went beyond language, or rather, invented one of its own. It helped me, in the end, to find my way back into the book.

Mad women. Attics. Discuss.

LW: First of all I’m not so sure that Evie is mad. Eccentric, yes, deluded – possibly. But mad? I’ll leave that to the reader. The point of the attic for Evie is a retreat from the outside world into one of her own organisation. Something akin to the womb, I guess, but with more clutter. So she’s different from the original madwoman in the attic – Bertha Mason in Jane Eyre, and later, following Jean Rhys’ amazing reclamation of

Bertha’s story, in Wide Sargasso Sea — because she hides away up there through choice. As opposed to Bertha, who’s shut up (in more ways than one) against her will. Though I suppose there is a parallel between Evie and Bertha/Antoinette in that they

end their stories by starting a fire.

Your meditation on memory and the past owes a lot to Proust. In fact, you cite him as an influence on this book. Have you read all seven

LW: Every writer I’ve ever read and loved has been an influence on this book, pretty much so it would be a bit wanky of me to single out just Proust. There’s some Dr Seuss in there as well. I’ve not read the whole of In Search of Lost Time. I’m currently in the middle of Volume 5. It’s brilliant stuff. Hilarious, sad, annoying and downright filthy. Proust claimed that his writing style was concise, which makes me laugh a lot,

because it’s so outrageous and yet so true. I’ve had to put it aside for research on the new book. I do most of my reading for pleasure when I go on holiday, and I mostly go on cycling holidays and Proust is a bit bulky. So unless I get a Kindle I’m going to have to forget about getting through all 7 volumes any time soon. Though I could do what I did with the fourth volume when I went cycling through France last summer, which was just to tear out chapters as I finished them, so that the book got lighter and lighter as I got closer to the end.

At one point, your narrator, Evie, tours America in the early seventies with an English rock star who closely resembles a Ziggy Stardust-era David Bowie. How did that come about?

LW: I mentioned earlier about suffering from writer’s block. So it was no surprise that Evie was in the same position. Evie got over it by transcribing documents written by other people (e.g. a diary kept by her lover) and I got over it by getting someone

else, my friend Natasha Soobramanien, to write those diary entries. David Bowie got dragged into it because I’d already told the publishers that Evie’s girlfriend would be a mime artist, and that she and Evie would travel around America together in the early 70s. So when Natasha came to write about their journey in the diary entries, she had them travel as part of Bowie’s entourage on his Ziggy Stardust tour of the US in 1972. I think mime was the link – Bowie trained as a mime. And Natasha saw Bowie/Ziggy as developing a theme I’d introduced earlier in the book – the concept of personality as theatrical event. Which fit in quite well with Bowie’s whole alter-ego thing. It’s funny but after reading that section I realised that however aurally fixated Evie is, she’s not that interested in music. It’s sound she’s obssessed with, and the two are not necessarily related in Evie’s sonic universe.

Tell us about your second novel.

LW: Natasha’s writing half of it. So hopefully it won’t take eight years to finish.

The Echo Chamber is out now, via Hamish and Hamilton