went to church

got coffee

went to take a shit

got coffee […]

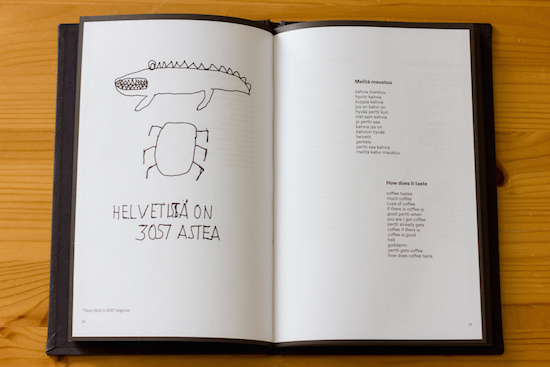

Last year, Ediciones Hungría in Mexico published Kalevi Helvetti, a book of writing and illustration by Finnish artist Pertti Kurikka alongside translations in English by Miissa Rantanen. Given that this column is going to explore the challenges of working with translated literature, the methods that translators find to communicate the things that can’t be said and what can be found in translation rather than lost, Pertti’s writing in translation seemed like a perfect place to start.

The ‘poems’ map out Pertti’s preoccupations with death, hell, daily life, self-hate, horror and playing in his punk band Petti Kurikan Nimipäivät (Pertti Kurikka’s Nameday, PKN for short). They are direct, confessional and cover similar territory as PKN’s lyrics: private anger, living in group homes, the relief of going out…and coffee.

How does it taste

coffee tastes

much coffee

cups of coffee

if there is coffee is

good pertti when

you are i got coffee

pertti already gets

coffee if there is

coffee is good

hell

goddamn

pertti gets coffee

how does coffee taste

Pertti Kalevi Kurikka was born in 1956 in Finland and grew up in orphanages and group homes. He’s been creating written work and music since 2004. His band, the aforementioned PKN, are well-known in Finland; their first album – a collection of long sold-out 7" EPs and cassettes – made it into the top-twenty of the Finnish album charts on its release. Their popularity was bolstered by the award-winning documentary Kovasikajuttu or The Punk Syndrome (2012), which follows the band in their daily lives and on tour, bringing them international recognition and allowing them to tour across the world, including in the UK.

As well as playing guitar in PKN, Pertti performs in bars and clubs as the Dracula-like character Kalevi Helvetti (Helvetti is Finnish for ‘hell’) with another musician playing a Moog synthisizer.

As his performances are largely improvised and his writing is comprised of diaries, lists and notes, Kalevi Helvetti documents a fraction of Pertti’s writings.

Rodrigo Téllez, the founder and director of Ediciones Hungría, first came in contact with PKN in 2012 during a festival in Finland, and then got in touch with the band’s manager Kalle Pajamaa when he saw Pertti’s illustrations in an article:

‘Kalle handed me hundreds of pages of texts and drawings, a treasure trove of Pertti’s creative output. The translator Miissa and I sat down to discuss what kinds of texts there were and we selected the most representative from his vast spectrum of writing: from random lists to reminders to poem-song-lyrical texts. We were very careful to showcase his different moods, from the really friendly to the angry to the plain weird. Looking back at this process and at the final product the word immediacy comes to mind. He is extremely honest, he has a rich imagination and inner world, his use of language and rhythm is so interesting. Artists work for years to achieve all this and in Pertti’s case it feels really natural’.

Miissa Rantanen isn’t a translator by trade, but had followed PKN and had met Pertti a few times. She was unsure as to whether she was up to translating Pertti’s poems:

‘…I tried to translate a poem just for fun. While doing it, I realised that the text itself isn’t that difficult to translate (for example it’s quite clear how to translate a sentence like "how does coffee taste"). The most difficult but also interesting thing was to get into Pertti’s world. For example: why is he talking about getting coffee instead of making or drinking it. I found that very compelling and kept going. The biggest challenge was the issue with spelling mistakes and how to deal with them.’

I remember when a journalist reviewed a Tracey Emin exhibition and complained that she found the spelling mistakes in her work irritating. Editing out grammar or spelling particular to the way someone expresses themself can undermine who speaks and what they have to say. But, as Miissa explains, deciding not to keep Pertti’s spelling mistakes was part of the compromise – and there always is a certain amount of compromise – of publishing and translating his writing:

‘At first the idea was to keep them in the English version as the mistakes play quite an essential role in the poems. I studied what kind of spelling mistakes people make in English if they have problems writing but the result felt fake. For example, melitä maustuu would be miltä maistuu (‘how does it taste’) when written correctly. In English I could add extra e-letters or mix a- and e-letters or change letters around but "how deose it teste" doesn’t really work the same way as it does Finnish. And it’s difficult to read. It’s also worth noting that the Finnish version was also edited. Pertti writes on a typewriter and it’s impossible to keep all the original mistakes and nuances when you transfer that kind of a text to computer.’

Pertti’s anger and self-destructive behaviour are his impetus to write, and as Kalle points out ‘writing is a way better way to punish yourself than actually hurting yourself.’ Kalle is on the receiving end of this anger, as well as PKN singer Kari and bass player Sami: ‘sami is so orphan that he can’t/ do anything’. In ‘WHAT DO YOU GRANNY SHOUT AT US ALL’ he tells an old lady where to go after shouting at him in the street: ‘and granny shouts so go to hell/fuckdamn/out of here.’

Pertti himself receives the most hate of all; he reflects back internalised abuse by hating himself for being disabled (‘I AM A MURDERER PERTTI/WANTS TO KILL PERTTI…BUT I JUST HATE PERTTI KURIKKA IS A PISSHEAD FUCKING/CRAZY DISABLED…WHY DO I WANT TO KILL PERTTI KURIKKA’) and feels ashamed for being angry, ending the whole book with a handwritten note as a sign of his tendency to be sensitive, apologetic and regretful: PERTTI APOLOGISES TO EVERYONE.

He’s preoccupied with hell (some of the homes Pertti grew up in were highly religious), and a mysterious and at times violent skeleton and a black ghost haunt many of the texts:

THE SKELETON COMES TO VISIT

the skeleton comes to visit

nobody dares to sleep

but hell is

hot just 1788 degrees

it is hot in hell it is

hot it is 1788 degrees

so is hell

is a hot place

and damn fuck

is it is damn

fuck it is hot is

hell pertti kurikka

it is damn and fuck

hell the skeleton is

visiting pertti

and the skeleton holds disco

and everybody dances rock n

roll the skeleton stabs

pertti kurikka crazy

man i smell bad

Alongside self-flagellation and self-hate through metaphorical violent acts, he is also preoccupied by personal hygiene and sexual health, brought about from being told off and reminded in homes, and shown in the poems ‘HYGIENE IS IMPORTANT’ (‘hygiene is/man doesn’t stink/hygiene/that disease won’t come//have to wash hands/that disease won’t come’) and ‘PERTTI USE CONDOM’ (a sort of note-to-self that ends ‘and everything is fine’).

Each institutional environment is different but the atmosphere tends to be the same, a certain repetitive void where a search for identity and comradeship is heightened, and the longing for individualisation and expression in a space full of systems, routines and regulations can be desperate.

–

mon it is music and home day

tue sami commands pertti

at juuso’s place visiting

wed pertti smells like shit

pertti kurikan nimipäivät

fri pertti fuck off kalle

shit it isn’t cool

but pertti came to work

pertti wants that everything

goes fine regards pertti kurikka

Last week Dan Duggan’s debut poetry collection Luxury of the Dispossessed (just published by Influx Press) came my way via Kit Caless and I recognised how comparable the two collections are. Dan’s collection charts his time spent on psychiatric wards having been sectioned under the Mental Health Act. Just as he sets out the ground-hog-day effect of being locked away (‘the dustcarts arrived at 4am, and/on fourteen mornings subsequent to this./Purgatory of a sort’), day release, his lasting and fleeting friendships, his self-harm and his attempted suicides, Pertti lists his weekly routines and enacts countless imaginary deaths (by shark, by skeleton, by vampire, by devil, by suicide), even getting to fulfil an unsuccessful attempt to kill himself at the end of one poem: ‘REGARDS PERTTI KURIKKA/ I JUMP IN FRONT OF A METRO TRAIN’. Though it’s also hard to tell to what extent the violence and monsters are part of his love of horror and the character of Kalevi Helvetti.

But just like …Dispossesed‘s blurb assures you, neither of these collections is purely ‘darkness and terror’. Both share the celebrations of quiet triumphs in regulated spaces and the particular ways individual identity and emotion fight to be expressed. Digressions give you back agency and control (refusing to eat, not washing) and the everyday treat becomes a king-making treasure (a Chinese takeaway, a coffee).

29.1211

We got coffee

we went to the snake house

and it was nice so thank you

very much that it was nice

we went to the snake house

big snake i got coffee

jukka and jp were at the house

again thank you that again

we went to the snake house

i went to eat

now pertti home

thank you that we went

to the snake house

venomous snake is dangerous snake

constrictor can just kill

just anybody

slightly disabled

and i don’t have a diagnosis

pertti is disabled

pertti is disabled

the snake is at pertti’s place

visiting the snake gets coffee

The snake appears at different times as a friend and as a killer and perhaps even as Pertti’s double or disability. It’s also connected to his love of ‘snaking’ where he pinches at the seams of clothing and hisses as if they contain or are snakes; something he started doing to the sleeves of the staff at the orphanage where he grew up. In The Punk Syndrome, Pertti announces that his jacket is ‘poisonous’ and that it’s ‘killed 400 people’ and that his manager Kalle’s ‘grey, green and white jacket isn’t poisonous’ but it can ‘strangle people to death.’

Kalevi Helvetti and Pertti Kurikka’s other writings have the power to alter perceptions and inspire, but most importantly, to just stun with its winning simplicity and honesty. As his publisher Téllez says: ‘I think of Pertti first and foremost as an artist, and I believe disability comes second. It is indeed a present element and it did make me reflect on the way society treats the disabled and mentally ill. Think of all the brilliant minds that we haven’t had a chance to listen to thanks to inadequate education and support from the government and society in general.’

You can visit the Ediciones Hungría website here: http://www.edicioneshungria.com and buy Kalevi Helvetti here: http://kalevihelvetti.com/.

PKN are currently in the running to be the Finnish entry for the Eurovision Song Contest: http://www.caughtinthecrossfire.com/music/news/pkn-punk-band-to-enter-eurovision/

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator and musician based in London. Her short fiction, poetry, articles and reviews have been published by The Quietus, Structo, Huck and Modern Poetry in Translation, and she has translated prose and poetry from German for Bloomsbury, PEN International and the Goethe-Institut. She edits the Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt. She plays in the bands Sauna Youth, Feature and Monotony.