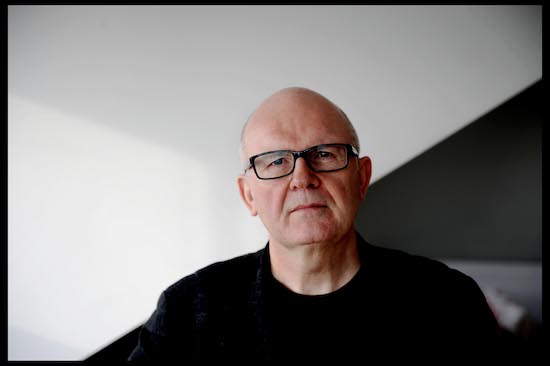

I should declare an interest. For ten years, I worked with Gordon Burn on a series of publications at Faber & Faber. We would meet, rarely, at the company’s then Queen Square offices, an independent survivor of Bloomsbury’s literary heyday five decades before. More often, we would meet in one (or a series) of the local pubs in the area. The Lamb on Lamb’s Conduit Street was a particular favourite in the winter months. Gordon loved the golden light and warmth, and the sense of a community of men brought together to drink and share stories as the light started to fade around 3 pm. He would often settle in and observe from a solo vantage point, always observing with the next or a future book in mind. A potent image in Born Yesterday describes a pub scene painted by the great pitman painter of the north-east, Norman Cornish: “the ease of association, the unselfconscious physical contact between the men”.

Our first meeting had been up the road in The Queen’s Larder in 1998, one of the smallest pubs in London and a meeting point for writers like Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney and John McGahern over the years at Faber. Gordon was deep in the writing of his grand-guignol masterpiece, Happy Like Murderers, and there was some anxiety on our part about meeting the publication date in September. Gordon delivered that book in chunks of chapters, which were copy-edited along the way over the summer. The final chapters came in perhaps three weeks prior to publication and Gordon, I remember, was unconvinced by my attempts to impress upon him the horror and the nightmares I had suffered in reading his account of Fred and Rose West. I was nervous around him. Working on his book had made me nervous.

Each and every writer works in a different way, this being a cocktail of methodology, pragmatism, procrastination and superstition. There are the morning writers; the likes of Anthony Burgess, who would boastfully produce several thousands of words each morning before a liquid lunch, completing a now-forgotten novel in six weeks. Unearthly powers, indeed. There are others – mainly male and childless – who write by night. There is a creative purity to this but the books are often damaged, literally lacking in light. Gordon Burn trained as a reporter in the 1960s. He would immerse himself in the subject and world of a book, along the way committing very little to the page by way of actual writing, or even notes. He had a magpie nature and a photographic memory. He would see stories everywhere and had the skills of a great collagist in the assembly of his material.

Gordon Burn’s untimely death at sixty-one robbed us of perhaps another half-dozen books that may have helped us understand the present moment: the unravelling of celebrity culture, which was always Gordon’s lodestar subject. I write this in the wake of the news that Ukraine has voted Volodymyr Zelensky, a comedian famous for playing the President on a TV show, into office. It has become commonplace amongst fans – those with a deep knowledge of Gordon Burn’s nine books and his sensibility – to associate these moments of dark comic serendipity with a writer who nearly always wrote about the present, or the recent past, but in the process anticipated the future, and recorded history.

It must have been late spring 2007 and I’d bought us an inexpensive and disappointing lunch at the Princess Louise in Holborn. Gordon would often arrive enthusing about Dave Eggers’ latest innovations at McSweeney’s Quarterly. It wouldn’t be long before the conversation turned to the events of the Big Brother House that week. This time, he was particularly animated and keen to discuss an idea he had: to write a novel in real time; a novel that would be true to the unfolding events of its subject and circumstances; a novel dictated by the news. The news as a novel. At the time, the news was dominated by something that the great aide-memoire Wikipedia now files under ‘Bridgend suicide incidents’. In 2007, there were at least nine victims, aged between 13 and 17. There were rumours of a suicide cult amongst teenagers in the benighted Welsh town. By 20 February 2018, some months after the publication of Born Yesterday, the total was up to 17 since the beginning of the previous year. Sharon Pritchard, mother of 15-year-old Nathaniel, said: “It has glamorised ways of taking your life as a way of getting attention without fully realising the tragic consequences.”

Gordon and I parted company that afternoon, and I returned to the office eager to share his idea to recast the news as a novel. However, I quickly found I lacked both the articulacy and intelligence, to say nothing of the vision, to fully comprehend what he was proposing. To compound this, I’m sure many of my colleagues viewed the idea as more of a conceptual and production challenge than a commercial opportunity. Luckily, the strong editorial culture at Faber supported and encouraged adventurous commissioning, and an existing contractual commitment (for a book on Bob Dylan, I think) was switched for the new project, which was christened Born Yesterday. The book would be animate and alive with the news of summer 2007, as soon as Gordon felt the moment was right. And that gave me a bit of grace to work out how I might talk to the world about the book, which is obviously a fundamental requirement for any editor.

Gordon spent a month or so following the disturbing frequency of teenage suicides in South Wales, but never committed to this as his subject. Perhaps, for all the tragedy of those lives lost in copycat self-harm, there were crucial ingredients missing in the Bridgend community horror story. Born Yesterday could have been an entirely different book had the events of 3 May in Praia da Luz not happened; at one point he was tempted to hijack the Sedgefield by-election (the then prime minister’s seat in the Commons), but thankfully we were saved from that particular putative iteration of the book.

Gordon was always drawn to mystery and the place where a popular image might capture the hidden currents and furtive mood of the country. It was the disappearance and apparent abduction of Madeleine McCann that galvanised Gordon in the making of Born Yesterday, and it’s the image of the coloboma in her right eye that haunts the text. It’s a book defined by ambiguities and echoes. In an interview with Marcus Harvey, ten years before, who was fielding controversy for his painting of Myra Hindley made up of children’s handprints, the artist offered this explanation: “I just thought that the handprint was one of the most dignified images that I could find. The most simple image of innocence absorbed in all that pain.”

So often it’s an image of innocence defiled, lost or shattered in an unsettling context that speaks with a universality about the world we live in. By establishing the archetypal lost child at the heart of a book that is all mystery, yet has no crime to be solved, Gordon created what would become arguably the first British auto-fiction experiment, and a work of literature that is also perhaps the final work of art to emerge from the now infamous YBA movement.

“In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible, and that nothing was true.”

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

There is something heroic in the act of a writer submitting himself to the mercy of the world for his material. It requires openness, submissiveness and a denial of the prime lubricants for the engine of fiction: causality and motivation. In making these decisions, Gordon sacrificed the authorial ego at the altar of the collective consciousness as it manifested itself in the summer of 2007, and the book survives as an ur-document recorded in the moment, almost in one take, of an instant that twelve years on, seems to uncannily prefigure our own. By forfeiting control of the narrative, and writing the book in as close to real time as possible, he was implicitly making a statement about powerlessness and generalised entropy. The book and its propitious timing represent both a winding down of the ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ years and a shadowy prophecy of the new truths that would come to shape the twenty-first century in Britain: fear, financial meltdown, demagoguery and, the sinister bassline that runs through the book, climate change.

Reading Born Yesterday twelve years after the events of that summer, and eleven years since the book was delivered to me at Faber in February 2008, feels like time travelling. The book has taken on a documentary feel and has a peculiar universality, because these were shared experiences, and there is a temptation to use words like visionary and prophetic when talking about books like this, a generation after publication. It’s a perplexed book constantly in search of a narrative, which ultimately becomes a book about Britain’s first and last celebrity prime minister (“The man with no shadow”), presiding over his Camelot manqué; a Britain that has lost the healthy glow it acquired in the Britpop years. Ironically, it’s the novel’s fierce commitment to the recording of the moment that makes it now seem so prescient and contemporary. Every age feels it’s in the grip of millenarian unravelling, and Born Yesterday is on some levels a book about how we have become distracted and disengaged from the reality of a world where the waters are rising and the animals are dying. But here’s Kim and Aggie to clear up your mess in How Clean Is Your House?; here’s Jade Goody, whose celebrity death-roll somehow becomes a national myth. There’s a sense in Born Yesterday that we’ve achieved a point of political and cultural constipation. Margaret Thatcher, Bob Geldof, Terry Wogan, J.K. Rowling, John Terry, Kate Middleton? Where are the heroes? Will Rafael Nadal save us? Even at this premature stage of his administration, there’s a sense Gordon Brown certainly won’t.

FULLALOVE: a celebration of Gordon Burn will take place at The Lexington (N1 9JB) on Tuesday 25 June, with readings from Cosey Fanni Tutti, Adelle Stripe, David Keenan and a performance by Andrew Weatherall. Tickets available here.