In 1988, Brisbane (Australia) held the World Expo. It was a pivotal moment, catapulting the region out from underneath a decades long shadow of corruption and bigotry that had been maintained by the then state government. It was also the moment Brisbane entered puberty, maturing out of its sketchy country town persona into a city that has subsequently grown into its own skin.

For me too, this was a critical year of transition, for not only was I on the brink of that awkwardness of puberty, but I was also discovering the world was so much bigger than I could possibly imagine.

The first discovery that opened the world to me was via music. Until the mid-80s, I had known nothing but the classical music piped into my parents car via the radio. I didn’t realise the car stereo was a potential spectrum of musical discovery. As far as I was aware there were just two classical broadcasters, neither of which seemed all that interesting. It was late night music programmes, such as the legendary all-night video program Rage, and cassettes passed from friends’ older brothers in the proceeding two years that started to crack open what had been a somewhat cloistered musical vista.

The second discovery was something more unexpected, but equally persistent. On Fridays, I would leave school and make my way into the city to score a lift home with my father. There was usually a gap of a couple of hours, from when I left school till when he would be finished for the day, and in that window I was free to roam Brisbane’s modest downtown.

It’s important to prefix this story and say that up until the mid to late 1990s, Australia, and especially Brisbane, felt like (and was) an incredibly long way away from, well, everything. It took time, effort and in many cases sheer good fortune to make connections to much of the music, books and films that would eventually captivate me. This story is, in some respects, one of serendipitous chance encounters that proved utterly formative and lasting in my life.

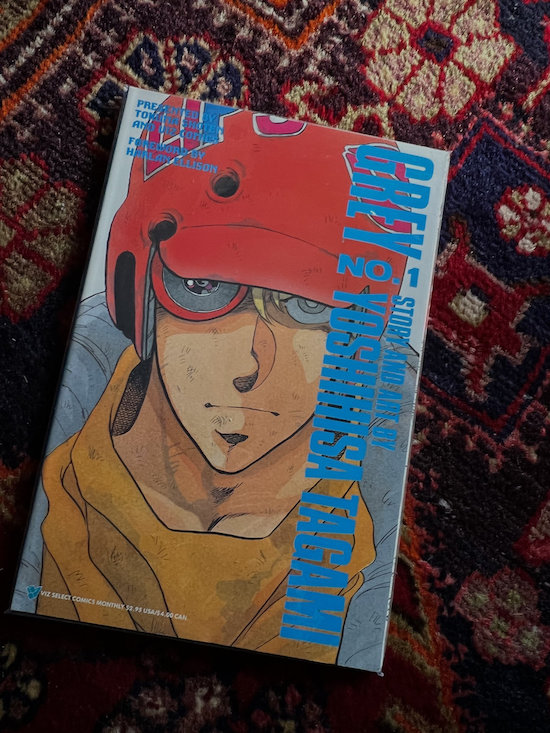

On most Friday afternoons, I split my time between games arcades, a couple of record stores (I still have a collection of cassettes bought during these years) and two comic shops. During these years, comic shops were a fairly nebulous space. They acted as points of accumulation for much more than just the superhero tropes that continue to dominate the Marvel and DC franchises. You’d often find fanzines, art books, photo books, bootleg (and official) VHS tapes of horror films and also anime (much of which was untranslated) and even the odd anime adjacent import CD or LP. It was in one of these stores that I discovered Grey, a work by Mangaka Yoshihisa Tagami, and by chance caught the first significant moments of Manga’s arrival in the West.

While it’s apt to say that Manga ‘arrived’ in the west in the late 1980s (though it should be noted Barefoot Gen was translated and published in the early 1980s), it’s important to recognise that anime, Japanese serialised cartoons, had already foreshadowed Manga’s arrival. From the early 1980s onward Australia and other western countries began to broadcast an array of anime regularly.

In Australia it was programs like Osamu Tezuka’s 1980s remake of Astroboy that dominated, alongside anime titles such as Tatsuo Yoshida’s Battle Of The Planets (in Japan, Science Ninja Team Gatchaman), Yoshinobu Niishizaki and Leiji Matsumoto’s Star Blazers (known in Japan as Battleship Yamato; curiously in the western dub, those sections of the story referencing Japan’s 20th century imperial history, from which the Yamato derived its name, were deleted) and Robotech, an American throw together of three unrelated real robot anime series that were rewritten into a long-form saga.

My interest in Manga – or more broadly Japanese popular culture – travelled in parallel with the screening of these early anime titles. One of my earliest memories of being excited about Japan was in later 1984, when my parents returned from a conference junket to Hong Kong with a small transforming robot from an anime call The Super Dimensional Fortress Macross (incidentally the anime’s popstar character was voiced by Mari Iijima whose debut album Rosé from 1983 was produced by Ryuichi Sakamoto and who also guested on Van Dyke Parks’ Tokyo Rose).

I have very strong memories not just of the toy, but more so its packaging; of the typography, the colours, the lay out and the language which to my young eyes looked so utterly compelling, simultaneously ancient and futuristic. This single object unlocked a sense of wonder and curiosity for me that still persists to this day. It’s hardly a surprise then that anytime I found anything related to Japanese film, music, anime, Kaiju or illustration, I was instantly drawn to it. It was this insatiable curiosity that led me to find the first issue of Grey.

Each week a shipment of comics would arrive at Daily Planet Comics, the store I first frequented. It was usually a few boxes of popular comics and the odd inclusion of something less familiar, and when the boxes arrived it was a scene not unlike those of the Tokyo fish market at Tsukiji. Titles were pulled from the boxes with a group of, mostly middle aged men, vying for the few limited copies of each title. As the kids in room, we were left to peruse whatever was left after the initial feeding frenzy was done, this usually amounted to a mixture of titles which were placed onto long racks where the covers of each comic were visible.

No one, including me, squabbled to get a copy of Grey as it came out of the box (notwithstanding the glowing introductory essay by legendary sci-fi writer-editor Harlan Ellison in its opening pages). It, along with a couple of other titles from Viz comics, found their way onto the long shelf later that afternoon and it’s there that I got hooked. I’m not really sure what it was that first grabbed me, my best guess is, like the robot toy my parent’s gifted me, it was Grey’s bold typography, the trademark drawing style and colour choice of Tagami, and likely the fact that the Manga’s cover image was so incongruous. Grey #1 featured a portrait of the Manga’s namesake, looking dishevelled with a strange headdress, best described as a bullet ridden baseball helmet with the words ‘Lips’ written across it.

Inside, a bleak post-apocalyptic world was traced into life, textured in dot and line screens, its stark black and white depictions somehow suggesting so much more than what was actually revealed on the page. Looking back, it seems ironic to have discovered a title such as Grey at a comic store whose name alone was so strongly rooted in a history of comic books that reflected the rampant aspirational American exceptionalism that continues to dominate today. Grey was nothing like the comics from North America. It offered, rather, a completely antithetical position to exceptionalism.

Instead of speaking to exception, heroism or super powers, an individual reigning over all, Grey spoke to irrelevance, isolation, loss, nihilism and distrust. It presented a portrait of a world that spoke to hardship and a day-to-day slog that was both relentless and quite possibly meaningless. It also spoke to a post-apocalyptic reality rooted in the emergent concerns of its present day: environmental degradation, artificial intelligence, entrenched poverty and the perpetuity of proxy wars as a means of constructing or at least encouraging economic prosperity.

When I picked up that first issue, I read over Harlan Ellison’s essay and while I’m sure some of it went right over my prepubescent head, some of it did not. Without doubt, this was the first time I encountered terms like class politics and also ideas around how artificial intelligence had implications, not just for how we come to understand sentience, but also how logic might play a role in the formation of these thought processes. Whilst we might tell ourselves we are logical thinkers, our actions often present a different story, and this disparity is at the heart of Tagami’s story.

It’s hard to quantify the impact this Manga had on me and likely on a generation of others who discovered it. Grey, alongside titles like Area 88, Mai The Psychic Girl, Appleseed and a little later Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind set the stage for what would become a worldwide boom in Manga, shifting it from a peripheral and culturally specific publication type into a centrepoint of comic culture.

These Manga also held the power to shift comics from their dominant demographic, to a new, broader audience. Manga addressed complex ideas within society, they examined interpersonal relations, identity and politics presenting them in a multiliteracy format that did not underestimate the aspirational intellect of its readers. It would be only a couple of years later that Akira would arrive and in its wake the full influence of Manga, and anime, on Western storytelling would be felt.

I rediscovered Grey last year following something of an extended period of YouTube trawling through OAV (original animation video) titles like Megazone 23 (a key inspiration for The Matrix), Armoured Trooper Votoms off-shoot Armor Hunter Mellowlink and later films such as Patlabor 2 (which just so happens to have one of the all-time great monologues that holds great relevance to this day) which I had read about but never had the chance to see (and even if I had seen them, like the Grey OAV, I’d watched the original Japanese versions with no subtitles).

Grey was not really a Manga I had thought about in several decades. But after re-reading it, I was acutely aware it – and likely some other Manga too – had helped to guide me through what was a fairly turbulent but utterly formative period of my life.

Approach, the record that I recently made, is a reflection on this Manga and on how life is an accumulation of all these small encounters. The album draws its inspiration from Tagami’s Manga and simultaneously is a nod of respect and admiration to him. It is also a sound postcard to a version of myself I don’t really (or can’t really) know any longer, but to whom I am immensely grateful. It was this unsteady and unresolved self, their curiosity and willingness to follow interests (without collapsing to other pressures and peer expectation), that inevitably allowed the me of now to exist.

is released via Room 40. Grey by Yoshihisa Tagami is available to read digitally from the Internet Archive