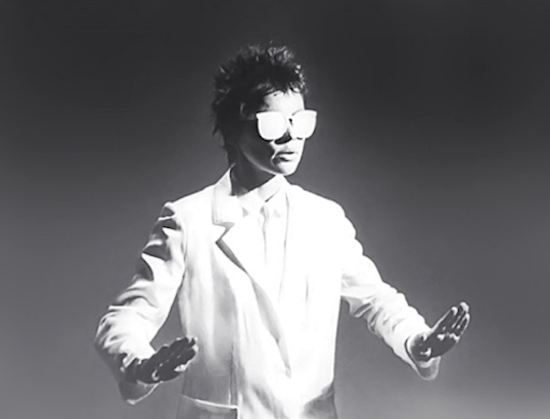

Laurie Anderson’s 1982 debut LP Big Science opens as if her voice has been waiting for us to show up: “Good Evening. This is your captain.” In welcoming listeners to board the plane, to hear the album, and indeed to behold her career, she offers coolheaded assurance. This space is well-prepared. You are in good hands. On the album’s cover, she wears a suit and tie: everything is professional. Then she announces the plane is about to crash.

That’s what they do, of course. Paul Virilio’s famous quip – “When you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash” – is generalizable when it comes to systems. And since the 1970s, Laurie Anderson has explored the glitches and inhumanities of systems far more diffuse than air traffic control: her topics include language, sound, business, and technology at large. Early in her career, small new works came fast across a variety of media, and so her project became one of organizing, juxtaposing, and optimizing them.

Her initial audience was mostly fellow downtown NYC artists, but factual talk of her eventual stardom was in the air. Reviewing a 1970s show, composer Tom Johnson wrote, “Some were speculating that, with the help of a good record producer, she would emerge as the ‘80s’ answer to Patti Smith.”

And indeed Anderson became a star. After debuting ‘O Superman’ live at Irving Plaza on May 11, 1980 – Mothers Day – she recorded the song with producer Roma Baran, and in the spring of 1981 her former production manager B. George had it pressed for release on microlabel One Ten Records. George was the author of a wide-angled punk discography called Volume, which had earned him the friendship of tastemaker John Peel.

When the BBC tastemaker invited George to guest DJ on his radio show in August 1981, ‘O Superman’ was the Trojan Horse. George recounts. “I think [John Peel] heard it the first time live that evening.” Fellow jockeys Simon Bates, Dave Lee Travis, and Richard Skinner immediately picked up on the record, giving it daytime airplay. The next morning, “It went to breakfast radio, which means that every mom in England knew the song.” says George.

Rough Trade records was keen to sign Anderson, but instead (with help from Baran) she called Karen Berg, a Warner Brothers A&R staffer who’d been lurking at her shows. Warner Brothers quickly picked up the rights to “O Superman,” and by mid October it had gone top-20 in sixteen countries, taking the number-two slot in the UK’s weirdest ever top-five.

1: ‘It’s My Party’ – Dave Stewart with Barbara Gaskin

2: ‘O Superman’ – Laurie Anderson

3: ‘The Birdie Song (Birdie Dance)’ – Tweets

4: ‘Thunder in the Mountains’ – Toyah

5: ‘Happy Birthday’ – Altered Images

Laurie Anderson may have toiled for fifteen years in NYC’s SoHo galleries and on the pages of ArtForum, achieving cult status in that world, but to her new global audience, she emerged from nowhere, fully formed like Athena. Seemingly overnight, she was an event: the first (perhaps the only) superstar of the multimedia avant-garde. As one reviewer wrote, “the world knows what a performance artist is now.”

Big Science came out six months later, and even today it still sounds sprawling and sublime. Its widescreen magnitude connoted both a sacred disembodied sentience and a profanely tedious corporate ubiquity. Together, these gesture toward everything-ness. Vitally, though, Big Science also illuminates cracks in the gigantic, and pries them open. In her own small ways, Anderson sizes up technology and authority, short-circuiting their logic with a humanity both heartfelt and wily.

“Her overall thesis is simple,” writes media scholar Bart Testa: “past/future… is a collapsed duality and this collapse has obliterated the present under its rubble.” Anderson’s early-1980s work doesn’t merely portray a world devoid of “now,” but its superhuman scale also erases “here” and anonymizes “us.” If the time of the “Renaissance man” ended when the alleged sum of human learning exceeded the individual’s capacity to understand, then Big Science marks the turning of another era: never mind the sum of knowledge, your brain is too puny to grasp even a single domain like public transportation in all its complexity. Fittingly, Time’s 1982 “Man of the Year” was the personal computer.

Science writer James Gleick waxes, “The birth of information theory came with its ruthless sacrifice of meaning – the very quality that gives information its value and its purpose.” Early on, Anderson understood this tradeoff: her nerve-wracking 1977 single ‘New York Social Life’ bombards us with enough smalltalk, phone ringing, and urban noise to make us tune out. The more data we have – the bigger the science – the less meaningful any of it becomes.

Knowledge too big to be known bears troubling implications for authority: if nobody understands air traffic control, city planning, or telephone networks (to say nothing of romantic relationships or the afterlife), then who is in charge? How can we know the world is running properly? Big Science orbits this empty circularity. Authority is faceless. There is no pilot.

To hear the album like this is to behold the moment when our creations become sentient, when power wields itself. This music’s stars and power brokers are “they” and “it”: anonymous, all-implicating, unknowably huge, fatally entrenched. The global plot is no longer the story of people or ecologies, but of the techno-economic mechanisms they serve, the inoperable parasites larger than the bodies they inhabit. It’s the modern condition underlying the 2008 declaration that America’s banks were “too big to fail.”

But Anderson offers hope. She consistently calls to mind human scales of time, magnitude, and presence – even if only in their defamiliarising absence. She leans in to the aesthetics of alienation, allowing us to imagine new pleasurable ways of submitting to industry, urban flow, and even surveillance.

Most importantly, though, Anderson enacts little glitches in big systems of authority. A pilot is somehow a caveman in ‘From the Air’. A backwards voice erupts from nowhere in ‘Example #22’. Her vocalization “ah” sticks like a broken record in ‘O Superman’. Big Science traces and pries open the human-sized rifts in superhuman systems.

Language is the system in which Anderson perhaps most adeptly finds stressors. Big Science’s closer ‘It Tango’ pushes innocuous words to their breaking points. The lyric begins, “She said: It looks. Don’t you think it looks a lot like rain? / He said: Isn’t it? Isn’t it just? Isn’t it just like a woman?” He, She, and It are tiny but ubiquitous signs, and we overfill them with assumptions about sex, agency, and proximity. These anonymizing stand-ins are both essential and extraneous, nothing and everything: not the bricks of meaning, but the mortar. Mixing speech and song to evoke pun, homonym, and pure sound, ‘It Tango’ bedevils each until its meanings multiply and crumble. Where they were overloaded, Anderson empties them – and in effigy she duly empties language and gender.

The song’s clockwork repetition calls to mind Steve Reich’s observation, “musical process makes possible that shift of attention away from he and she and you and me outwards towards it.” Fittingly, that two-letter pronoun can wind listeners into album-wide tangles: It’s the heat; It’s a sky-blue sky; It could be you; I no longer love it; It was a large room; It’s a place about seventy miles east of here. The issue is central to Anderson’s oft-recycled riff on philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “If you can’t talk about it, point to it.” And out there in the world beyond, the unit It recurs with a ubiquity both eerie and mundane.

So the song’s concluding volta is significant: “Your eyes: it’s a day’s work just looking into them.” The unexpected tenderness here offsets the facelessness of the song. Certainly in “a day’s work” we recognize the exhausting unpaid emotional labor that women provide men in misunderstandings like this song. In a sweeter listening, pop audiences might savor a note of romance, where the exhaustion of “a day’s work” is love’s breathlessness. Alternatively, the line self-referentially tells us how difficult it is to connect with an audience – to look into their eyes – through the one-way medium of recorded sound, and with the meagre tools of so few words. Or, for those whom capitalism affords a little humanity, the lyric pits the mammalian comfort of eye contact as the reward after a day of exploitation.

In any event, this final text pulls us from obscure dialogue. And those lyrics are also a needed reminder that not all of life is encompassed in the structures, governments, and data. Capitalism, Christianity, the internet, binary gender, and language are all built so big that they can seemingly lock out competing worldviews – indeed Anderson has paraphrased Frederic Jameson and Mark Fisher in interviews, acknowledging, “It’s easier for people to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” But you have choices beyond accepting “he-said” / “she-said” scripts of gendered interaction, whether or not they’re easy to imagine – just as there exist alternatives to capitalist realism. A good first step is to insist on a pesky humanism: to carve out a lucid now in which individual experiences matter, where mechanisms serve you (not the other way around). Another way out of the bind is to change the conversation. The last two lines of ‘It Tango’ – indeed the concluding words of Big Science – do both.

This quintessentially Andersonian move may be merely symbolic. But it’s precisely the “mere”-ness of that symbolism that Big Science aims to negate, escape, or overwrite. In the stuff of memory there is no difference between the real and the symbolic – or to put it in Anderson’s terms, between the time and the record of the time. When art leaves you remembering (as Big Science does) that it can crash airplanes through its medial confines, escape by car into the endless night, walk and fall through its own frame, burn down the building, and look into your eyes, then indeed it can do all that.

Heard this way, the album’s stakes can be staggering, and their gambit is that Big Science is not science fiction (as some mistake it) but science reality. For if Laurie Anderson succeeds in portraying technologised society in its immensity; if she succeeds in helping us to forget whether a story is hers or our own; if she succeeds in the Fluxus project of escaping the theatre, breaking open the frame, and making art indistinguishable from the praxis of life – then she eyes something truly emancipatory.

This is the heart beating in Big Science: when the song ‘Born, Never Asked’ asserts, “you’re free,” it gestures beyond the LP’s 40 minutes. Remember (from some prior something) that your freedom is unconditional, which seems an impossible thing for a conditional text to claim.

The way to exceed a medium such as an album is to call attention to its very mediation: to point it out – not just so that we see it, but so that we can recognize it as something to see past. Anderson’s are the hands reaching impossibly from the screen to shake our shoulders. She indicates the glassy surface of our panoptic lens so we might look through it, no longer mistaking it for the real thing. Art can’t actually say anything else, just as language can’t express anything beyond language. But it’s ultimately toward this else that Big Science gestures. If you can’t talk about it, point to it. Our freedom lies not in the expressible, but exactly over its border.

To fall short of actualizing this radical freedom is no failure of the art heralding it. Rather, our own imagination fails to suppose beyond the theatre. Don’t be too tough on yourself (“It’s hard to be free,” Anderson once told Anohni in an interview). But don’t give up too easy either. Jump out of the plane. You are not alone.

Laurie Anderson’s Big Science by Alex Reed is published by Oxford University Press