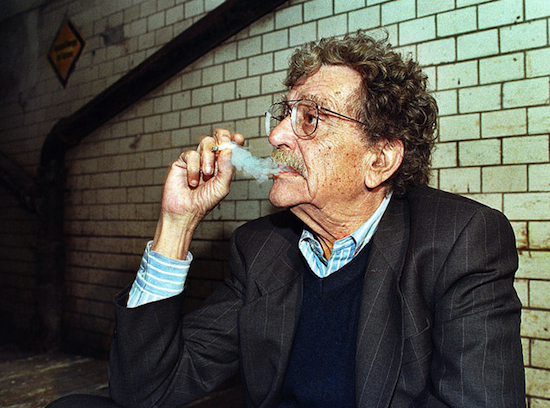

Whenever a book of letters of someone great is published, I tend to harbor healthy skepticism of the editor’s intentions. Nearly without fail, it seems, vain editorial pursuits hinder establishing anything like a fair representation of a fantastic figure. Unfortunately, the introduction to this new book is no exception. Nevertheless, the letters of the late American satirical novelist Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (1922 – 2007) could be described as a heart-breaking compendium dotted with the writer’s personal disasters and regrets. Yes friends, take delight. Six years after Vonnegut’s passing, we may now quietly indulge our private voyeuristic pleasures in reading the personal and professional letters of the exuberant author, to whom sorrow was no stranger. (His mother famously committed suicide on Mother’s Day.) Setting aside the rather sycophantic introduction, written by his long-time friend, author Dan Wakefield, the assemblage of letters notably demonstrates a strong thread of Vonnegut’s often misinterpreted vulnerability. Although his possible suffering from PTSD may be hinted at throughout the letters, it goes without mention.

Rarely mentioned too are his bouts of depression, which his son Mark has made notorious through two memoirs of his own battle with mental illness. (Mark was diagnosed schizophrenic in 1971.) Vonnegut wrote in 1972, ‘As for my happiness: I live from day to day and hour to hour. I know elation. I know despair. A doctor has prescribed pills for depression, which I take from time to time, as instructed. I still have life in me as an artist.’ Though he mentions medication here, in a rare appearance, perhaps self-medication with alcohol was a more frequent companion to his mental pain. Twelve years later in February of 1984, he was hospitalized in New York City when he overdosed on the potentially lethal combination of sleeping pills and booze.

In the introduction to Mark Vonnegut’s memoir Armageddon in Retrospect, he wrote it was ‘a bizarre, surreal incident when he took too many pills and ended up in a pysch hospital, but it never felt like he was in any danger. Within a day he was bouncing around the dayroom playing Ping-Pong and making friends. It seemed like he was not doing a very convincing imitation of someone with mental illness.’ And Vonnegut senior seemed to feel similarly; in a letter written to Walter Miller in 1984, he described the scenario in his ubiquitous nonchalant, Hoosier manner: ‘The real sickies are on the fourth, fifth and sixth floors. [He was on the short-termer third floor at Saint Vincent’s.] I played a lot of pingpong and eightball with them in the rec hall on the roof. They were so heavily sedated that they believed me no matter what I said the score was. Now I’m an outpatient, allowed to carry matches again.’

To be sure, despite his occasional popping of prescription medications for what he self-described as ‘monopolar depression,’ the more mainstream recreational drugs simply weren’t his style, as the editor carefully makes clear. Vonnegut wrote an amusing anecdote in A Man Without a Country on getting high with Jerry Garcia: ‘I did smoke a joint of marijuana once with Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead, just to be sociable. It didn’t seem to do anything to me one way or the other, so I never did it again.’ Instead, he stuck to his Pall Malls and whiskey – the latter used to a degree that often undoubtedly belied the detriment of his familial relationships. Near the end of his life, Vonnegut wrote, ‘Somebody should have told me that getting drunk, while fashionable, was dangerous and stupid.’ Perhaps at this juncture, it may have been useful for the editor to look at the voices of the author’s two wives – Jane Marie Cox and Jill Krementz, who surely suffered the brunt end of his proverbial drinking shtick. (The extraordinary Jane, his first wife and the mother of his three children, died in late 1986 from cancer. Jane served as the ‘middle-man’ between Kurt and his agents in the early days, as a typical writer-wife in the Fifties would do.)

Vonnegut, who came from a family with a history of severe mental illness, never was formally diagnosed with PTSD. He was captured by the Germans whilst serving as a private in the American army during the chaos of the Battle of the Bulge. His collective experiences as a PoW from 1944-1945 certainly shaped his psyche and later impacted his eventual writings. While captive in Dresden, the twenty-two year old Kurt wrote back home to his family in Indianapolis:

‘I’ve been a prisoner of war since December 19th, 1944, when our division was cut to ribbons by Hitler’s last desperate thrust through Luxemburg and Belgium. Seven Fanatical Panzer Divisions hit us and cut us off from the rest of Hodges’ First Army. The other American Divisions on our flanks managed to pull out: We were obliged to stay and fight. Bayonets aren’t much good against tanks: Our ammunition, food and medical supplies gave out and our casualties out-numbered those who could still fight – so we gave up. The 106th got a Presidential Citation and some British Decoration from Montgomery for it, I’m told, but I’ll be damned if it was worth it. I was one of the few who weren’t wounded. For that much thank God.’

In 1989, over forty years after the Second World War, Vonnegut penned in a letter to a friend, ‘Maybe my fundamental home is in Dresden, since that is where my great adventure took place, and where one hundred of us selected at random were bonded by tremendous violence into a brotherhood – and then dispersed to hell and gone.’ These memories certainly surfaced as inspiration and impetus for the 1969 novel Slaughter-house Five, which shot the writer onto the international literary map.

Well, to borrow Vonnegut’s most famous cliché, and so it goes… Among the last words he wrote were supremely benevolent ones, to be shared with a live audience: ‘And how should we behave during this Apocalypse? We should be unusually kind to one another, certainly. But we should also stop being so serious. Jokes help a lot. And get a dog, if you don’t already have one…’

Kurt Vonnegut: Letters is our now, published by Vintage Books