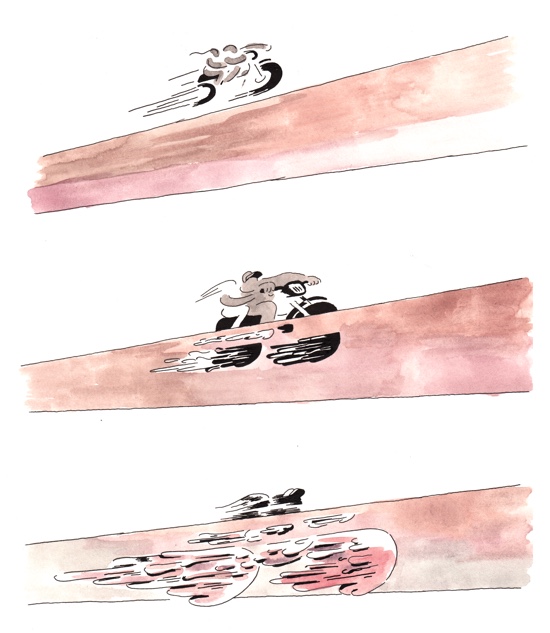

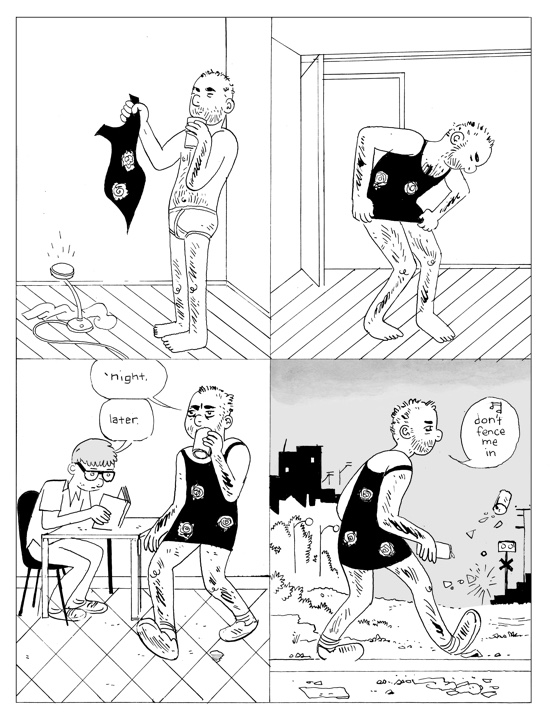

For comics, cartoonist and editor Sammy Harkham sees opportunity in the anthology format to contextualise a varying degree of work, and to offer cartoonists a platform to have shorter stories published. He said the proliferation of the graphic novel in the last decade has shifted focus away from what comics do best – the one to two-page units or “just the random thought” which exude the medium’s energy and ability.

“By putting all that stuff together [in an anthology] you get this great tension between different material, building this larger whole," Harkham said. "This is a way for me to get excited about comics, and to curate a context for myself to exist in as a cartoonist."

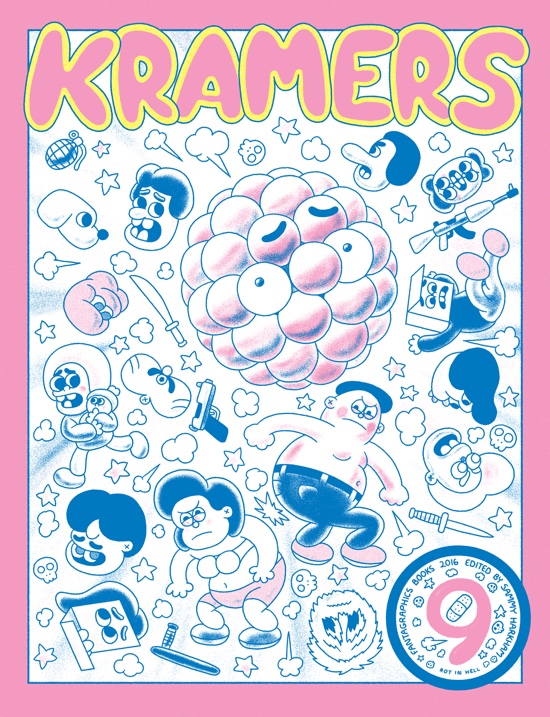

recently published Kramers Ergot #9, the anthology title Harkham has edited since 2000. Like most comics anthologies, it began as a vehicle for Harkham to publish himself and friends, but the book morphed into an institution as it continued.

The release of the series’ fourth issue in 2004 has been described as a watershed moment for the medium because it broadened the range of acceptable aesthetics within comics. It did this by publishing a rising generation of cartoonists, such as Anders Nilsen, Renee French, Marc Bell and Genevieve Castree, in a book which challenged the design sensibility of comics anthologies.

“The book changed the visual syntax of comics anthologies enough that it might be hard to imagine how different it looked at the time: the chunky, full-color, phone book-sized thing with the rainbow-colored crayon wrap-around cover, no title or issue number on the cover, multiple title pages — and a cryptic table of contents without page numbers,” critic and Best American Comics editor Bill Kartalopoulos told the Comics Reporter in 2010.

Harkham curated successive issues with an audience holding high expectations. Kramers Ergot became the “face of the new,” a title to read to catch a glimpse of what was next in comics. Harkham hasn’t exactly played into these expectations. He said the pressure associated with them once bothered him, but he’s accepted the relationship his audience holds with the series, saying it is valid.

Now at Fantagraphics, a publisher with wide distribution and an earned reputation, Kramers Ergot resembles a polished, veteran publication. Harkham insists it is still his personal project, though. The series makes sense of his ever-changing tastes by publishing work he admires, and presents it in considered sequence through measured, thoughtful design.

Harkham’s approach to anthology is to produce an independent work which displays its editor’s perspective, not a haphazard assortment of vagabond art.

"It’s not my life’s work,” he said. “The reason I say that is I don’t want to make it sound important, or that it’s necessary. I like to think of it as a fun project.

“I think the only thing that would really stop me in my tracks is if it stops selling. If it doesn’t sell well, then there isn’t really interest.”

Harkham said Kramers Ergot sells between 3500 and 5000 copies per issue. These numbers aren’t impressive in any grand scheme, but in alternative publishing this is a solid return. Harkham said the readership is split between a devoted comics audience and those who buy the books because they’re attractive objects.

But this trivializes it. Harkham understands the series provides its contributors with an outlet and a chance to receive some validation for the work they create. He said the medium lacks its own literary journal where cartoonists can submit short stories or strips for print publication and a small paycheck.

"Cartoonists lose their minds because the only way you can work for 10 years, with no return, is by thinking what you do has value. And so the only way to think it has value is by boosting your own ego – even though nothing is supporting this,” Harkham said. “Nothing is supporting this thought that you’re good at what you do, or that your work has value (laughs) except this drive. That’s insane. That’s what crazy people do. "But that’s what most cartoonists are like. They’re nuts."

There’s also few opportunities to work with an editor. Harkham notes that we rarely think of those who collaborated with great writers and helped them along. Great cartoonists, such as Chester Brown, can excel without this relationship. He doesn’t even know what an editor would do with Brown’s work. But “for the rest of us a great editor is a fantastic thing."

Harkham said he was a vocal and hands-on editor crafting the new issue. Differing from past practices, he invited contributors to submit pieces without guarantee they would be published, despite any name recognition they may carry in comics. He said the act of submitting work for consideration encourages a cartoonist to work harder, so they offer up their best effort. This produces a better book, overall.

“It’s the way it should be,” contributor and cartoonist John Pham said.

Pham continued, saying Harkham isn’t someone who can be nailed to any particular aesthetic or style because his tastes are broad. He said Harkham responds to what an individual cartoonist offers. This makes him a reliable source for quality comics.

“Sometimes you trust an editor,” Pham said. “The Criterion Collection is a trusted editor people use to find things they didn’t know about.”

Harkham observes that few in the medium have considered packaging comics in any prestige format such as The Criterion Collection, and this is both a positive and negative thing. Harkham said he enjoys work that’s casually delivered and direct. He said Daniel Clowes’ solo anthology series Eightball was exceptional because it was an embarrassing object – a comic book with staples – that contained such excellent storytelling. In some ways, this dichotomy may make comics the form it is.

Harkharm argues packaging for a lot of comics is bad, though. He said this element of presentation is the context in which comics are capsulised. “Kramers is what I think is a nice delivery system for this work that gives it some respect. You can publish somebody that’s been published before, but if you publish them well, if you know how to showcase them well, it’s like you’ve never seen their work before,” he said.