A pop pantheon. Well of course pop stars are gods in a way. Larger than life, commanding our attention, and worshipped by millions. When at their best, they open up our consciousness to magnificent new worldviews, wider realms that can lead one– to put it in Kabbalistic terms – to either an enhanced desire to receive in order to share (and thus making, as Belinda Carlisle sang, heaven a place on Earth) or the desire to receive for the Self alone (the true meaning of Satanism). In The Wicked + The Divine, main character Laura says of a concert early on in Issue 1, ‘It’s not a mass. It’s what masses aspire to be.’ I know I’m not the only one who has never felt what religion promises – that blissful oneness with everything in the Universe – when in a church or similar, though have experienced it hundreds of times at gigs or clubs, utterly enchanted by the power of the music. But pop stars are people too. Humans, who often full-on pursue that latter selfish path like ball lightning gone fucking berserk. As Wicked + Divine writer Kieron Gillen puts it – ‘problematic people doing problematic things’ (and that needn’t be limited to pop stars). But what they bring back from that journey often resonates with us all. Which is in itself a little problematic if you think about it.

"Every ninety years twelve gods return as young people. They are loved. They are hated. In two years, they are all dead. The year is 2014. It’s happening again. It’s happening now."

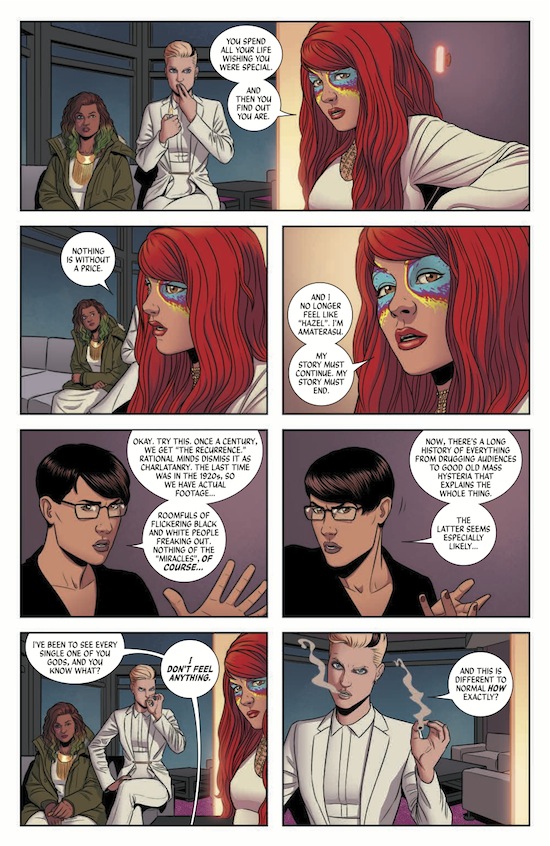

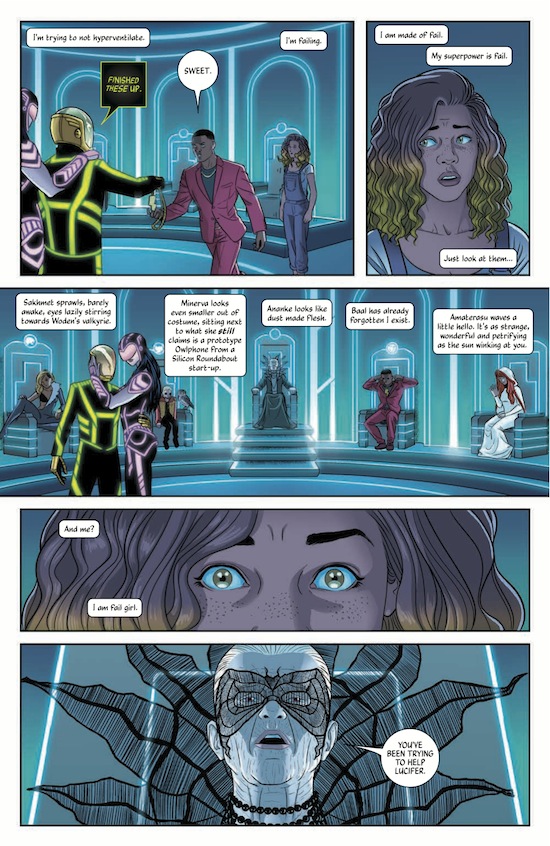

Relevant to our era, these gods in The Wicked + The Divine have now returned as pop stars. But gods have rules too and Lucifer’s broken them (what do you expect?). She’s killed two would-be assassins with a click of her fingers, and this same fate has been doled out to the judge at her trial. However, this last murder appears to be a set-up. Lucifer’s held in a mortal prison as well as being ostracised by her fellow gods. But überfan Laura is determined to prove Lucifer’s innocence, or at least figure out what is going on within the immortal community.

As I say in our latest Quietus Comics Column, I find a lot of this juvenile and appalling. It’s meant to be. (‘Problematic’, remember?) But it’s great writing, expertly rendered on the page by artist Jamie McKelvie. And it gets better as it goes on, delving more into what makes these characters what they are, the pain and pathos behind their chaotic world, how they relate to each other and how we relate to them. Earlier this month, The Wicked + The Divine won Best Comic at the 3rd Annual British Comic Awards. The first five issues are now collected as The Faust Act and having read them multiple times, I honestly can’t wait for more. There’s that excitement, just like in pop music.

Gillen has noted that The Wicked + The Divine is ‘primarily about the creators of art’. We discuss this more below. With its Bowie, Prince, and Kate Bush archetypes, to name but a few, its cast contains more major players than the titular pun of this piece would imply. But with such a stylish creation, something that evokes the pop music world so well, I found myself wondering what would its creators be like? Having begotten this problematic world, would they in turn be ‘dicks’, as they themselves describe some of their own characters? [Baphomet from WicDiv for example or all of the cast of Phonogram, Gillen & McKelvie’s first critically acclaimed series. If you don’t know it and you like pop music, I imagine you’d love it] I’m pleased to report No. Chatting to them over Skype, both Gillen and McKelvie come across as two humble gentlemen, pleased with their success but not taking it for granted. What struck me most was the thoughtfulness behind and obvious care they feel towards their art. Whilst at the same time being able to have a good deal of fun with it and that therein lies the all-important glory of pop.

Kieron Gillen (left), Jamie McKelvie (right)

So what made you want to deal with ‘problematic people doing problematic things’? How do you find the impetus to keep doing it?

(both think for a while then laugh)

Kieron Gillen: I was tweeting gifs of Dangerous Liaisons earlier (laughs) so it’s clearly something that’s on my mind.

Jamie McKelvie: It’s the stuff we’ve always been interested in. If you go back to Phonogram, David Kohl’s a dick, well, all of the Phonogram characters are (laughs) in various different ways.

KG: I think people are basically problematic.

JM: Yeah.

KG: I think people who think people are basically nice are deluded. I think people are great and interesting despite themselves rather than because of themselves. There are many things about the human condition I love but I look at any of my friends or anyone I’ve really known, and you do see the big flaws of ego sweeping right through them. I like doing characters who can learn things about themselves. This is why problematic people are much more interesting. People who say ‘well, the world is the problem’, all that really teaches you is a lack of empathy for anything. If the world’s the problem, that means you’re fine, and there’s a complete lack of self-awareness. Whereas if you start with problematic people you can talk more honestly and interestingly about failings. As anybody who loves pop knows, how problematic are all their favourite pop stars? The question is what is our relation to the people who inspire us incredibly but at the same time have flawed natures as human brings and how those two things feed into one another.

I’ve read you talk about searching for meaning. How much of it is an explicit search for meaning versus immersing yourself in the work itself with the confidence you’ll find meaning there within?

KG: It’s tricky, innit? Basically this is us trying to finish off our present stage in our creative careers, I would say. It’s building upon everything we’ve ever done before, both together and separately. So there’s a quite explicitly ‘kill your darlings’ about it all and immolating ourselves. At least for me, I hope that by doing this I will come out the other end and realise more about what I want to do next. So that’s kind of the search for meaning. At the same time there are some narrative lines in the book I know, but will be surprised about how some of it ends – some characters are problems, and I’m trying to decode their answers. Many of the characters are expressly about the certain contradictions of being a creative artist or a human being. There’s endings which I know up front and there’s others that are a little more flexible. As in I know the ideas of what to they’re going to explore, what it’s actually gonna be about for the characters facing off each other. Even my most planned work has similar flourishes. Even something as structured as Journey Into Mystery for Marvel had some very significant flourishes added relatively late in the day. Leah would be a good example of that.

In the non-verbal realm, how does that work for you, Jamie?

JM: (thinks for a while) I don’t know. I’m not sure if that’s something you can necessarily answer as the artist. The way I see it with the stuff I work on with Kieron, or any book you work on with a different writer, it’s not necessarily my story but I’m the one who decides how it’s told, in a way. Whatever’s in the script, it’s my work that people see.

KG: Any generalisation of the way comics work is nonsense obviously, but the way comics work, or at least the way we work, with the big idea/structure stuff, is I set the problems and Jamie solves them. I don’t want to say I’m the director cause that’s not true but at least on the larger scale I’ve got ideas on how to solve the problem in the script. I present them. And Jamie? He’s more like all the cast and crew. So it’s like ‘Jamie, how do you feel playing this role?’ rather than me specifically acting like a tyrant. I may have the original idea of a character, but it’s not really a character until Jamie acts them out. At least that’s how I see what you do, Jamie. (Jamie has been agreeing with all this all along). Especially as we go on it’s quite dark material, how do you feel drawing that kind of stuff?

JM: Yeah, it’s a weird one. It’s interesting how invested you get in it when you’re drawing stuff. You have to get into this character’s head, how they act, think, and feel, and how that’s reflected in the drawing. You have to think about how they come across in how they dress and their body language and all these kind of things. You get a lot more invested in the story than you would perhaps think you would just drawing it. You have to really think about becoming the character, which is weird, cause you’re just drawing lines on a page.

Who’s your favourite character to draw, Jamie?

JM: (thinks, then deliberately) Right now, it’s The Morrigan, cause she’s just a lot of fun to draw. We put together the style blog last year and just put in any image that appeals to us in terms of the aesthetic of Wicked + Divine. The Morrigan’s one who came together very early on in my head and I knew exactly what I wanted for her and how she looks.

All of them, really. I have a great time with all of them because they’re all quite different from each other, different challenges. Some of them are easier than others. Inanna was more difficult because the pop star that he’s mostly aligned with has such a strong visual image, I wanted to make sure it wasn’t basically exactly the same. The visual image you have in your head to start with is so strong but it’s not what you want the final thing to be. Whereas with The Morrigan she was more her own character straight away. I love her because she’s not specifically one thing…

KG: There’s more people in her, no pun intended (laughs) [The Morrigan is traditionally a trio of goddesses]

Talk me through the creation of a character.

KG: People ask me ‘what came first, the god or the pop star?’ and it really just depends. I was really interested in all the Phoenician and Semitic religions and I thought it was quite interesting that there were all these different Baals. I knew I wanted to do a Baal. But then I thought but who could Baal be?

There’s other ones where it’s completely the other way around. Where we had a pop star we wanted to use. Like The Morrigan is an example. She started with the Pixies record ‘Tame’. A lot of other stuff is crammed into The Morrigan but I got the image of her being this Pixies idea of the incestuous sci-fi South of America. I wanted to apply that to British fairy lore. She wandered away from that quite a bit and ended up in a very different place but that’s part of The Morrigan’s core. I also wanted to do a Florence Welch/Kate Bush archetype, that’s where Amaterasu comes from. And I wasn’t sure what god they were gonna be. Originally I was considering making them part of The Morrigan, but then I thought no, I’ll make that Amaterasu for reasons which will be explained down the line.

And sometimes it happened at the same time, Bowie as Lucifer was immediate! When we cast it, we had a long list of gods and pop stars we wanted to use, and had to narrow it down to twelve. I asked Jamie ‘is there any particular archetype you want to explore?’ I knew I wanted to use Inanna, but until Jamie suggested Prince I didn’t know who he was gonna be modeled on and then it suddenly made a lot of sense.

JM: Once Kieron produced the bible of the characters, I started the style blog, pulling together many ideas of what I wanted to do with characters and styles and things like that. This went on for six months or so and really started to solidify around January, maybe a bit before. It was pretty much on a case by case of when they first appear in the comic (laughs), those are the characters I have to design first.

I do a lot of my planning and my design in my head, which is very frustrating for people who put together the collections of comics and want backup sketches and stuff in the back. They sit in my head for a while and I pay attention to things, the world around me basically, and let it all percolate through. I end up with how I want the character to look pretty solidly with the first few drawings I’ve done. Then I send them over to Kieron and he hasn’t really made any changes to any of the characters. We talked it through quite a lot beforehand anyway so we knew what we wanted to do with them.

KG: When Jamie draws the characters, that’s what the character is. I suppose it’s the way the collaboration aspect comes in.

JM: Characters evolve as the book goes along. Sometimes my idea of them might change slightly.

KG: It accounts for style. Jamie has room to play with a pop star’s look, cause pop stars can change their look. (laughs)

You mentioned this a few times about WicDiv being a pop song. Want to say more about this?

KG: It really winds people up. (both laugh heartily) It’s how we want the work to feel. As much as you can dance to a comic, I want you to be able to dance to this. I want people to sing along, if you will. That’s the intent, a lightness of touch with heaviness of content. And there’s a juxtaposition between the genre. The way I always thought about Phonogram was we’re doing really wanky stories but we’re cramming them into a genre story. And that of course makes it harder to take the more serious stuff seriously. Which is entirely fine because that’s how pop music works. There’s a fundamental disreputability to pop music. And that’s kinda what I mean when I say it’s a pop song. As in yes, we’re dealing with some serious shit here but at the same time, you may not be able to take it seriously. And that’s fine because that contrast between the two is what we’re trying to evoke. Also it means we’ll sell a lot of copies (laughter from both)

It’s the part of you that wants to listen to a song 20 times a day when you fall in love with it. We want to change people. ‘This band could save your life’ says it all, I guess. We would never want everyone to be completely obsessed by it but some people could really buy into it and then maybe start to explore. The art I fell in love with did that to me. So I’d like to think there’s a nudge in what we do to do that to other people. That’s the aim.

So the first trade is called The Faust Act. Faust is also mentioned on the very first page of Phonogram.

KG: It’s useful, isn’t it? I find it an interesting construct. The ‘this is a gift, and this is the price’. There’s something fundamental there – what are the deals being made? The nature of knowing something is wrong. Cause in the real world, if the devil really came and offered me anything for my soul, I would have to turn it down cause you’ve just proved the existence of souls. (laughs) If you genuinely believe in this deal, you shouldn’t do it, because it makes no fucking sense if you actually think about it in any way (laughs). But in fiction, that’s an interesting device. Fiction is about difficult positions and what people do. And I also like that it’s a really bad pun.

JM: Which we’re a fan of. Well not so much a fan of, the puns-

KG: We cannot resist them.

JM: No. As much as I hate them. The worst thing about this one was that it wasn’t my pun, but it was my prompting. There was a different title at first. And then I suggested something Faust, and he came up with ‘Faust Act’.

KG: Second arc will be Fandemonium. I came straight in with a pun. The working title for the first one was ‘Sympathy For You Know Who’. Fairly obvious allusion. But a bit crap though, so we didn’t do that (laughs). A good title is an enormous surprise, and a great joy. When I got ‘Immaterial Girl’ for Phonogram, I was very happy. I was like ‘that is perfect’.

So what is going on with Phonogram?

JM: I start drawing it in about six months, once this arc is over. Then I’m doing that while we have the guest artists on Wicked + Divine for six issues. Six rather than five is the plan, which allows me to get Phonogram done. Very exciting.

KG: It’s about the plot we started in the second series about the war of personality between Emily Aster and the girl behind the mirror – the half of her personality she sold for power. About a decade on from the original faustian pact. The relationship between the pair. The deal goes bad, and they basically swap place. Emily Aster is lost in a universe of music videos and images and the half that was trapped takes over Emily’s life. That’s the basic structure of the story.

That letter in Issue 3 about how well you guys portray women was great. Do you have more thoughts about this?

KG: We get quite a lot of emails, and they’re always kind, but when people say anything like that, it’s enormously complimentary. It’s not really for us to say how well we portray women. It matters to us because…anything I say will sound fucking banal…but it’s just like these are our friends and we’re trying to draw people and the world we know. And a lot of it is how Jamie carries people, how he observes and how he sees people. Anybody can fuck up but it does really matter to us.

JM: We just try to present people as human beings basically, that’s what it comes down to. As much as I can, even if they’re gods. Just trying to pay attention. Yeah, you’re right, it’s not really up to us to say how well we’re doing but we try.

KG: You can’t please everybody but that we generally do ok means a lot to us. When people come up to us and we see the audience we get, that also means a lot to us.

You’ve chosen to tell the story through a young girl. Was that a conscious decision?

KG: A little bit. I live in Lewisham, near Brockley [where Laura lives], and I looked around my neighborhood and saw the girls on the street or on the bus. It wasn’t initially the teenage girls I thought of, I was actually thinking about the mothers with their kids on the bus. And I just thought ‘it would be really good for these girls to grow up and there’s a character like them available as a hero figure in a major comic book series.’ Because why not? There isn’t enough. So that was at least part of the motivation.

Laura has an interesting set of experiences and her family background isn’t too extreme. Her family’s quite nice. We get more of that family in the second arc. But it’s her desires being too big for her body is what it ends up being about. I’m delving into parts of me that I have been, or people I’ve known to some degree. But the initial urge did come from that looking at the bus and thinking ‘why not? I should dig into this’. And it would make Jamie draw curly hair and Jamie loves drawing curly hair (laughs)

JM: I keep doing it to myself as well. Curly hair is difficult to draw and freckles are annoying to draw and I gave the lead character both (laughs). I like putting challenges for myself though. I wish there was a way to automate them but there’s not, I handdraw the freckles every time.

Any further thoughts?

KG: It’s the kind of book I would give to my friends no matter if they’re interested in comics or not. Despite the fact that it’s a very comic book-y comic book. (laughs)

JM: I don’t wanna say I like doing books that aren’t for comics people cause that’s not true, and I love doing the mainstream stuff as well, but I like bringing in stuff from outside of comics when I work. Which was a part of comics up until the 90s and then the mainstream sort of turned in on itself. Which is a strange thing cause occasionally people get really angry with you that you’re bringing in outside influences and they see that as you thinking you’re, I don’t know, cool or something. The idea of being cool is laughable but… Comics are a part of pop culture, they should take from all of the other elements of pop culture and feed off it and feed back into it. It’s nice when that is then reflected in your readership. Even with Young Avengers we’d get people saying ‘this is the first comic I ever read’, which is amazing. And we’re getting that a lot with Wicked + Divine too.

KG: I do like being someone’s first comic. And I like being someone’s gateway comic. As in take Young Avengers readers who some of them haven’t actually read anything that wasn’t Marvel and taking them to a slightly different place and coming out the other end maybe into a different scene. The idea of actually being that gateway. So much of the stuff I’ve loved has been gateway pop, as in pop that’s led to other pop, and I’ve always liked bands who list their influences and are actually honest about it. So there’s that. I do like that. As a creator, you want the work to be good but there’s also that we love the medium and part of me would also like to leave Comics in a better place than we found it.

I’m thinking Gillen & McKelvie will do just that.

The Wicked + The Divine: The Faust Act is out now in all good comics shops. And the series will continue with Issue 6 on December 17