To clarify the Twitter storm raging around Kenneth Goldsmith, Vanessa Place and other prominent conceptualist poets, you need to get a handle on three questions:

What is “gringpo” and what’s wrong with it?

What does this have to do with you and your reading?

And what can you do about it?

Let’s start at the beginning.

1: Background

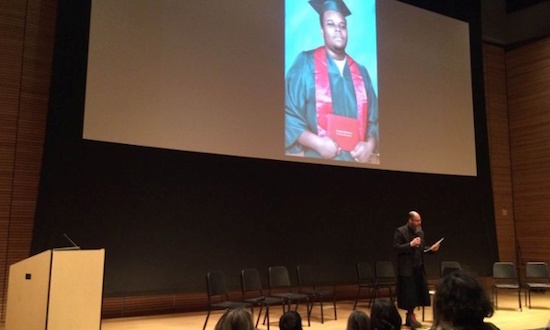

Middle of March, the ivy league halls of Brown University, and conceptualist poet-provocateur Kenneth Goldsmith is in trouble again.Known for his “conceptualist writing” practice of taking existing texts and reframing them as poetry, Goldsmith performed a cut-and-paste version of the official autopsy report of Michael Brown, the teenager killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri, last summer. He called it a poem. He called it ‘The Body of Michael Brown’. He also drove his conceptualist craft on to a massive theoretico-practical reef.

To onlookers, Goldsmith, from his tenured position of security and cultural power, had reappropriated an act of violence which it is very difficult to imagine happening to somebody from his background. In doing so he appeared to subordinate a human life to a literary experiment. Goldsmith defended himself behind complex theoretical explanations, but to anybody looking it was as straightforward as poet Kima Jones put it on Twitter: Goldsmith “made a thing…for a crowd…out of a black boy’s dead body…”

This moment has shown more than any other that if it looks like racism and sounds like racism, it’s racism – whatever the convoluted theoretical reasons you might try to offer in defence of blatant and useless provocation. Coming full circle out of his sub-Barthesian “intransitive writing” projects, Goldsmith’s gestures align him with an older, more insidious game: turning other lives into a blank slate on which to map out your own ideological position.

The incident gave rise to a cross-border dispute, with Mexican poets attacking the racist reappropriation inherent in Goldsmith’s gesture – but stopping short of an unequivocal condemnation of conceptualist practice.

Some time ago, Goldsmith’s writer colleague Vanessa Place set up a Twitter feed which spools out “remixed” (in this case, directly quoted) text from Gone With the Wind, drawing attention to the text’s pretence towards rendering then-current African-American English. To cap it off, the profile pic is Mammy – a racist archetype lifted from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When Place was nominated to the Associated Writing Programs board – a body which oversees the work of U.S. creative writing programs, their affiliated institutions, and their prospective applicants – a furious online argument broke out.

WHEN YOUR CRITIQUE ERASES BLACKNESS

WHEN IT DISMISSES & HUMILIATES THE POLITICS OF BLACK VOICES

THAT IS ANTI-BLACKNESS

— Mongrel Coalition (@AgainstGringpo) May 20, 2015A Twitter account called Mongrel Coalition, under the handle “@againstgringpo”. “Gringpo” is a portmanteau of “gringo” and “poetics”, used by Mongrel Coalition to define and criticise the perceived White male hegemony within U.S. poetic practice.

The Coalition is an anonymous individual or collective whose mission is to monitor and take down the worst excesses of gringpo wherever they find it, their hyper-articulate all-caps volleys against cis-het, White-centric poetic movements having earned them gleeful support and righteous indignation across the blogosphere. But Mongrel Coalition does not just attack American writers: they also zero-in on that strain in Mexican literature which aims at the wholesale importation of U.S. cultural models – at the expense of real and productive engagement with the Mexico around them.

By casting an uncompromising critical eye over both American and Mexican literatures, the Coalition has exposed the massive imbalances which characterise the ecology of power in North American literary theory and practice.

2: Gringpo and its Discontents:

As said, “gringpo” isn’t just a U.S. phenomenon. It’s a tendency that runs from Chiapas to Alaska, and one that invites accusations of self-colonisation from the Mongrel Coalition.

Among those offering a partial defence of conceptualism – while also trying to escape fire from the Mongrel Coalition – are a number of prominent Mexican writers.

Heriberto Yépez is a poet and writer from Tijuana, working at the Baja California Autonomous University’s Faculty of Humanities. In March, he came out with a measured but disapproving article in his column of the left-of-centre newspaper Milenio [trans.] highlighting the “conceptual inconsistency” – more than the outright racism – of Goldsmith’s Michael Brown stunt.

In May, however, he leapt to the defence [trans.] of his writer colleague, Jorge Carrión, whose article – ‘Conceptual Writers: An Overview – had earned him the wrath of the Mongrel Coalition.

In his defence of Carrión, Yépez does accept that Goldsmith’s text is a “racist appropriation”. But, just last night, Yépez announced that he was pulling out of the Berkeley Poetry Festival: the gesture, he says, was made in solidarity with Vanessa Place, but also in protest at "fascist popular demand".

The blog post breaks down somewhat towards the end, with fractured calls to "end Capitalism", and statements linking conceptualist practice to a "500-year" decolonising struggle "between Norths and Souths". However, the issue is that Yépez does not appear to see the contradiction between attacking racism and defending a colleague whose critical work aligns him with its proponents.

This is more than just a critical spat between Twitter users: this is about the position U.S. poetry occupies in Mexico. This isn’t just about conceptualism, Goldsmith and Vanessa Place: this is about what gringpo means for readers and writers of Mexican literature.

Polemical static aside, Mongrel Coalition offers a clear vision of gringpo’s pernicious, undermining influence on contemporary Mexican literature on both sides of the U.S. border. The issue is not the integration of foreign modes or techniques into a “Mexican” style. What causes problems is the uncritical and wholesale adoption of modes which respond to a different set of social and cultural imperatives.

This is a long-standing phenomenon in Mexican literature. One recent example might be José Vicente Anaya’s Beatnik imitation: long after the Ginsberg and Kerouac had moved on or died, Anaya’s own fractured typographics (and use of the ampersand) went on and on – and on – throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. The end result is a somewhat bloodless idiom that can’t do justice to lived Mexican experience.

3: Data:

All the same, it’s important to look beyond conceptualism to the discursive power structures that lie behind the movement. Gestures like Goldsmith’s and Place’s are the extreme, unreflective expression of deep-seated inequalities.

In fact, they hold a mirror up to chronic, institutionalised imbalances in Mexican literature. It is more important to address these issues than it is to import new ones.

The books a literature chooses to translate into its principal language reflect – perhaps more clearly than any other index – that literature’s values, but also its limitations.

Let’s explore this idea in relation to two canonical Mexican anthologies of poetry in translation: of the 30 U.S. poets in Agustí Bartra’s canonical 1955 Antología de la poesía norteamericana, only five are women. Dickinson? Amy Lowell? Marianne Moore? Edna St. Vincent Millay? Elizabeth Bishop? Right on all five – except for Elizabeth Bishop, instead of whom we have Muriel Rukeyser.

The volume opens with three pages on America’s “Aboriginal Voice” – a problematic idea for another day – which only serve to reinforce the conception of non-European literatures as anonymous, parochial, glassy-eyed, animistic evocations of the seasons. The only named POC writer is the rather anodyne Langston Hughes, included partially for the “note of rebellion” Bartra claims he represents.

Forty years later, Octavio Paz oversaw the last edition of his collected translations, Versiones y diversions. The volume’s 57 authors include just two women: Elizabeth Bishop and Dorothy Parker.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that in the intervening years – and in line with much of the rest of the world – the Mexican publishing industry would have grown beyond the male chauvinism that characterises Paz’s and Bartra’s choice of authors. The Fundación de Letras Mexicanas (FLM) keeps a database for all poetry publications in Mexico – including poetry in translation. Even cursory scan of the titles would seem to suggest that absolutely nothing has changed in the intervening twenty years.

The database reveals a massive overemphasis on figures considered “canonical”. Authors translated between 1995 and the present include Virgil, Homer, Anacreontic fragments, Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Leopardi. Of the 10 books of poetry in translation published in Mexico in 2013, Rae Armantrout and Ali Ahmad Said Esber rub shoulders with Homer and Mallarmé. The following year, 12 books of poetry in translation were published in Mexico in 2014. Only one was by a woman: a selection from Adrienne Rich’s work.

The FLM’s data reflects the extent to which women, POC, indigenous language and LGBTQ writers remain just as under-represented in the Mexican publishing mainstream as were sixty years ago.

The question now – both for readers and writers – is how we get these voices into the mainstream.

4: Towards a More Expansive Translation:

Bartra’s failure to include more women’s voices in his 1955 selection is only part of the picture.

Three years before the anthology was published, in 1952, then-President Miguel Alemán inaugurated the new seat of the National Autonomous University (UNAM): still the largest university in Latin America.

We have to see Bartra in context. As a Catalan exile fleeing the Spanish Civil War, he’s part of a moment where horizons were opening to a newly literate population. The UNAM is still a place apart. Located on the city’s southern edge, you can look in one direction and see only smog blur, towers of glass and steel, the noise and chaos of one of the world’s only true megacities. But turn away from the city. The other view opens onto the curves of dormant volcanoes like dinosaurs’ backs, and ozone-blue sky.

Bartra was facing in the right direction. He just didn’t go far enough.

His way forward is still the best way forward – but only if translation becomes integrated into the ordinary practices of reading and writing.

Only the right kind of translation can do this. That kind of translation must be capable of rethinking literature itself.