It’s a Saturday night in 1993 and you’re looking for a place to go out, maybe a club, maybe a rave. A friend knows someone who knows someone who’s having a house party. When you arrive you put your bottle in the kitchen. The living room is pitch black, the furniture’s been pushed back against the walls, and the first thing that hits you is the sound. The system is booming, your heart is pounding, you don’t know where you end and the music begins. It’s cramped because there are so many people. There’s not a lot of space to dance, but you’re still dancing. Everyone’s dancing. Rubbing shoulders, bumping elbows, nudging each other, but there’s no antagonism.

The walls are wet because everyone’s sweating. You don’t feel the cold until you get outside, raid your bag for a change of clothes, something dry. You leave the house, spend the next hour on a night bus, and crash home before five in the morning.

Scenes like these fill the pages of Two Fingas’ novels – time capsules for the jungle, bass, and rave scenes of the early 1990s. The pseudonym of Andrew Green, he placed the everyday life of young, working class, Black characters at the centre of his books – and watched as they navigated work, romance, sex, and music. The novels have been labelled as ‘tower block psychedelia’ and ‘avant-pulp anomalies’ by Sukhdev Sandhu, and texts of ‘London gnosis, backstreet Modernism’ by author China Miéville.

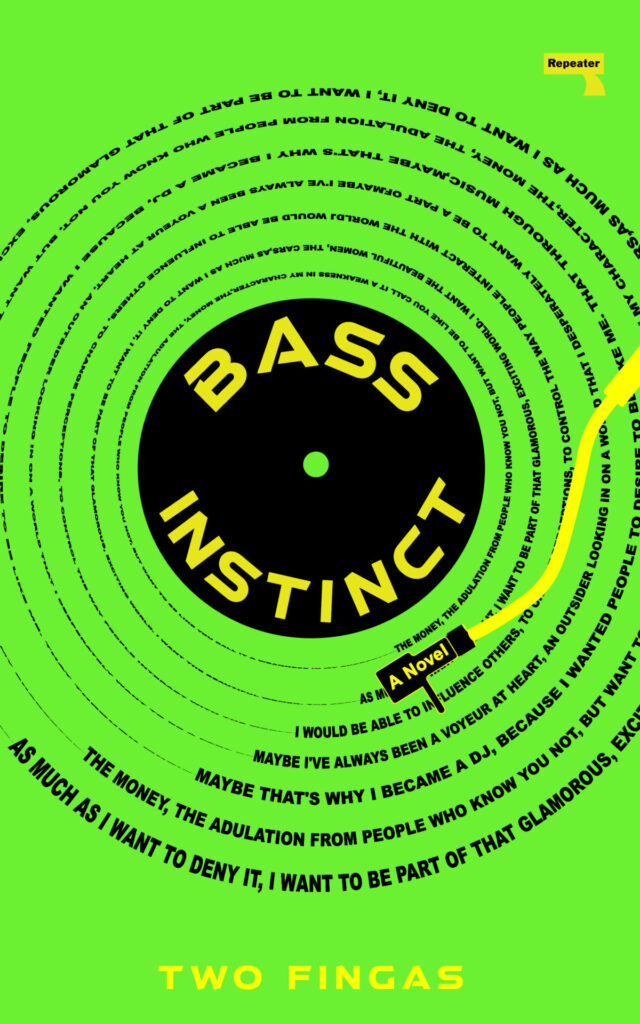

Green wrote not as an observer, but as a participant of these scenes – attending parties and writing about them as a music journalist. Although his perspective is unique, however, his books fell out of print for 30 years. Amidst a cultural re-examining of unappreciated texts from marginalised writers, Green’s novels have been revived by Repeater Books to reclaim their place as essential threads in the tapestry of the capital’s literary and musical history. His second novel, Bass Instinct, will be re-released later this month.

Green was born in 1973 in South London to parents who’d emigrated from the Caribbean. “It was a working class, estate family,” Green, who grew up in Vauxhall, tells tQ. “If I wanted to go out I could. There was no parental supervision. My mum was working two jobs, so you look after yourself.” Like the surrounding areas of Stockwell and Brixton, Vauxhall had a large Black population primarily made up of both British-born and immigrants of Caribbean, southern African, and west African heritage, so when Green did start going out, the places he visited were saturated with this influence – venues like Fridge Bar (next to what is now Electric Brixton) and Mass Club (in the basement of St Matthew’s Church). “It didn’t feel like there was pandering to certain demographics, or any desire to. There weren’t as many venues – and the venues that were available were predominantly Black.” It was in these spaces that Green’s taste in music began to take shape, but even elsewhere the discovery of new music always felt like a communal activity, “whether it was listening to pirate stations, or going to weddings, or parties and hearing it there.”

As rare groove became increasingly commercial in the final years of the 1980s, with major labels began releasing compilations of previously hard to acquire records, its impact on the club scene faded. The nightlife scene split between acid house, dub, and breakbeat – all of which were higher tempo, electronic forward, and attracted younger audiences. Warehouses had provided a new, culturally mixed space for ravers – but one that was soon co-opted by an increasingly middle class crowd drawn in first by ecstasy, and then watered down by sponsorship, ticketing, and security. “The more white people that know your sound and your scene, the less excited and engaged a Black audience becomes,” says Green. “It’s the idea of commercialisation and selling out. As soon as that rears its head, your Black audience moves to something else.”

Jungle provided an energetic, music-centric, dance-forward space for working class, Black communities to inhabit. “I wanted to be in jeans and trainers and jumping up and down and dancing. I never liked being in spaces where people didn’t want to do that,” says Green. “So jungle and drum & bass was perfect – because it was perfect for me. Or I was perfect for it, because it moulded me to what it needed me to be.”

Pirate radios would broadcast between Friday night and Sunday morning, telling listeners where to go and what to listen to. Knowledge was passed through word of mouth or through these broadcasts – and so the crowd remained urban. “If you’re out from the suburbs and you don’t get that radio station, you’d have no idea what’s happening,” Green says. “The same people that were making it were the same people living on the 12th floor of the council estate that I was on, putting their aerial on the 20th floor so they can get their station out there.”

Green spent his late teenage years and early adulthood immersed in this music, hearing it at house parties, in illegal raves in the suburbs of London, and in clubs. “You had house in one room and you had jungle in this small, grimy space. You had to know about it,” he recalls. Green began writing about music culture for magazines like Mixmag, Trace, and Touch – then he was approached by a man named Jake Lingwood.

Lingwood was an editor interested in the subcultures of London and saw the club scenes of the 1990s as descendents of 1950s mod culture. He was setting up an imprint called Backstreets, which would give readers an inside look into scenes that they were interested in but didn’t feel confident enough to enter, and was looking for book-length stories to publish. His approach was intentionally coarse, drawing inspiration from pulp fiction and youthsploitation novels. Lingwood was trying to see what Wolf Mankowitz’s Expresso Bongo (which chronicled the music industry of 1950s Soho) or Richard Allen’s Skinhead (which explored the violence of subculture in the 1960s) would say if they were written in 1990s Brixton. Potential authors were given just a few months to write 80,000 words on an advance of £1,000.

Green remembers thinking “Fuck it, why not?”. He chose the name Two Fingas, taken from a line spoken by Spike Lee’s character Mookie in Do The Right Thing, and began writing. His first book, Junglist (which he co-wrote with Eddie Otchere) came out when he was 21, his next Bass Instinct when he was 23, and Evil Eye when he was 25. “I was just trying to document Black people enjoying Black music – and not from the outside.”

Writing the novels also provided Green with an opportunity to recognise the music and the scenes that were relevant to him but underappreciated culturally. “I did Erykah Badu’s first interview for Mixmag because no one else wanted to do it,” he says. “I interviewed Aaliyah as a teenager when her first album came out because no one knew if she was important or not.”

Green’s experience in magazines had shown him that music was only seen as worth writing about if someone with power decided it was important. Editors weren’t championing jungle or bass, so there was no writing on Black music that Green felt was “pertinent to what young Black people were going through”.

As a response, Green wrote fast-paced, stream of consciousness novels that spoke to the everyday. “I was telling stories about what I wanted life to be like or what it could be like. The things that I’d experienced that I wanted to repurpose and put on paper.” Their protagonists are young Black men, working in unrewarding jobs, navigating sexual encounters and fantasies, and pursuing music. Bass Instinct follows Eder O’niah, a bike courier who is processing the death of his friend who was hit by a car. He spends the novel searching for the record that made him want to be a DJ which he heard only once, in passing, 10 years before the story takes place.

The books stand alone as one of the few cultural relics from the era that was solely made by the scene’s participants; documentaries like 1994’s A London Some ‘Ting Dis were wardened by institutions like the BBC and capturing the vitality of the scene wasn’t easy for individuals. “Jungle is from a time when there wasn’t that kind of digital democratisation. You had to be quite dedicated to actually take photos or film.”

Even though they’re now seen as an archive of music history, Green’s never thought of his novels from the point of posterity. “They’re supposed to be kind of fragments of a moment. Like a time capsule that no one was ever supposed to dig up again. When I was writing, I had no view on how long they’d exist for or whether people would be interested in them,” he says, “And it’s not that I’m documenting it as an archive for future ages. I’m documenting it because I’m involved in it.”

The sustained interest in jungle doesn’t surprise Green, though. Even as he danced in rooms full of people in the 1990s, jungle felt like the most important thing in the world, bigger than the specific moment. “Jungle is of its time and outside of its time. It’s fucking futuristic. It’s like science fiction,” he says, “You could be in any kind of place – New Zealand, Argentina, Japan, and you could put it on and it would smash, you know? That’s where the longevity comes from. Jungle just crushes; I can’t explain that.”

Junglist and Bass Instinct have become definitive documents for a specific time and sound of London’s music – but for Green, the idea of the scene was so much larger than people working around the music, more expansive than the ravers and the clubbers.“ I remember I was at a barbeque that was full of Black people and the DJ played ‘Scenario’ by A Tribe Called Quest. Every person in there knew all the words and everyone was going through the motions, just waiting for Busta’s verse to come on. And that for me was just like the quintessential experience of what a scene is – people that are involved without having to shout. But we’re in a scene because we understand this.”

“We know what the best part of a song is, and that’s what we’re waiting for. We enjoy all the song but that bit, yeah, that’s the bit that we love.”

Bass Instinct is published by Repeater Books, and can be purchased here.