The summer is upon us, and that means comics festivals. This weekend it’s ELCAF with a typically fine array of exhibitors, talks and workshops. Tim Bird’s The Great North Wood is launching there, so after you’ve read the review below it’ll be a chance to score a signed copy, and no doubt many of the books featured here will be available. The increasing trend for smaller festivals continues with the South London Comic & Zine Fair on Saturday 14th July at Stanley Halls, South Norwood, running the ‘free entry and booze available’ formula ably demonstrated at CECAF a fortnight ago. After that, the scene moves North with Thought Bubble in mid-September.

Other events of note very much include the Myriad First Graphic Novel competition, not least because Jenny Robins of this parish is one of the seven shortlisted artists. Results are announced on Thursday 5th July.

Now, on to the comics.

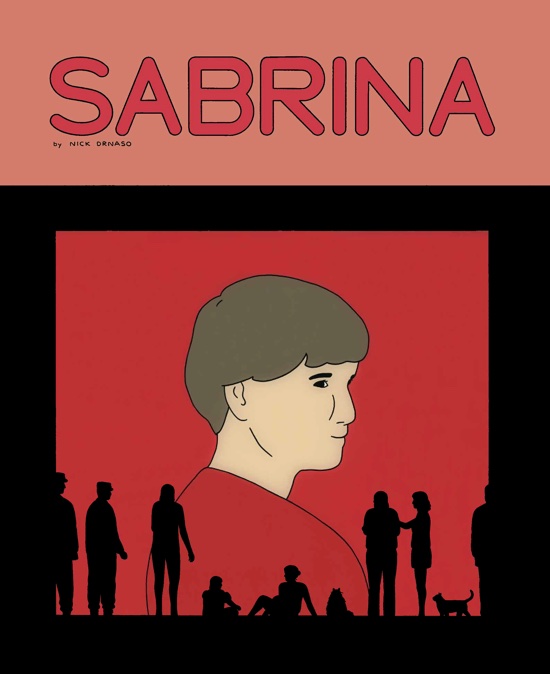

Nick Drnaso – Sabrina

(Granta – UK / Drawn and Quarterly – North America)

What with many things being suboptimal in these times, there’s certainly an appetite for art that captures a snapshot of the moment. It’s not like history isn’t going to have things to say about the global present, so there’s much to appreciate about an interesting take. Those who read Nick Drnaso’s previous book, Beverley, will be used to his precise, dispassionate delivery where shocking revelations slip out like chitchat about the weather. As excellent as that was, this new graphic novel is a serious step up in terms of his ability to pinpoint the exact moment we are living in now. Of course, considering that this will have been started several years ago, it’s also impressive as an act of prophecy.

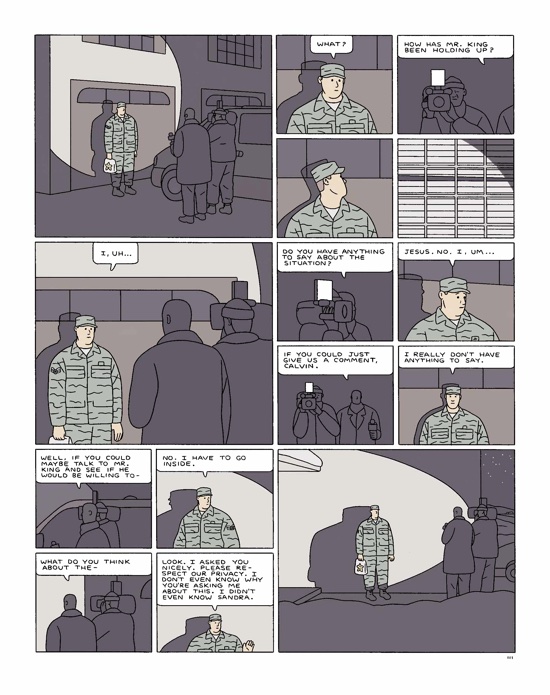

Despite the title, Sabrina does not appear in this book. Her disappearance is simultaneously at its heart and entirely absent from it. Instead of focusing on her, we see the impact on those affected by what has happened to her, distancing us. Much of the time we follow a soldier, Calvin, trying to support an old friend Teddy who is struggling to process what has happened to his girlfriend. Calvin doesn’t really know what to do, and by focusing on him not Teddy, Drnaso pushes us another step back from Sabrina. Similarly, a friend tries her best to support Sabrina’s sister, offering a visualisation of reaching a state of calm that is briefly implied to be a success before revealing to be utterly bereft of effect. It’s a pain that can’t be made better by doing anything.

Of the things that follow, some are distinctively American, such as the people who feel able to process their feelings only by carrying out mass shootings. Drnaso explores the risks of giving attention to killers and speculating on their motives rather than focusing on the victims. There’s also a radio DJ who appears to be of a similar ilk to the egregious Alex Jones, spouting conspiracy theories and seeing false flags everywhere. More universally, we see the angry young men of the internet and MRA forums, with the inevitable doxxing and death threats. Sabrina conveys the combination of bafflement, impotence and terror that must arise when one receives threats via rambling, paranoid emails from strangers. Lost, angry people lash out, fed by a corrupt media.

Drnaso draws his characters in such a way that we get very little facial detail; eyes are often just small, solid dots in impassive faces, somehow conveying just enough to make the events horribly real. As with his previous book, the soft colours and bland locations belie the events he depicts. Structurally, the pacing is flawless, such as in a scene triggered by a missing radio where the use of darkness combined with skilful panel sequencing generates serious tension. In both form and content Sabrina is a masterpiece, and cannot be recommended highly enough Pete Redrup

Laurie Halse Anderson & Emily Carroll – Speak: The Graphic Novel

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR))

Speak was originally published as a novel in 1999, and filmed a few years later; the 2018 incarnation is a graphic novel. Emily Carroll is an excellent choice of cartoonist, her fluid line and unerring knack for creating genuine horror a natural fit for the structure and subject matter. The book starts with a fairly typical account of being ostracised at high school. For the UK reader, much of this would be impossibly alien were it not familiar from popular culture. I mean, pep rallies? Just try that with a bunch of British 14 year olds. However, gradual details emerge of why Melinda is being shunned, something to do with a party that got shut down when she called the police. We can’t see the horror yet, but thanks to Caroll’s unparalleled ability to express terror we can see that it is horrific for her.

Other than art, not much is positive for her, at school or at home. Her only friend, a new girl, seems as good a fit as Ed Sheeran as singer/songwriter for GNOD. Home has nothing to offer, just two parents so at odds with each other that Melinda barely figures, and she descends into mute isolation, only able to express herself in her art class. It’s not without humour – the school mascot, originally trojans, was changed as it did not send a strong abstinence message. The process of choosing and then settling on a new one is repeatedly played for laughs, cropping up at frequent intervals.

Obviously, we find out what happened. And obviously, there’s a narrative arc whereby things improve. I have no intention of detailing this, but it’s well worth sticking around for. This is a powerful account of an all too common situation, stunningly illustrated as anyone who has encountered Caroll’s work would expect. Every page has a different layout, frequently with skilful use of negative space combined with evocative lettering, that draws the reader fully into the narrative, perfectly communicating Melinda’s state of mind throughout. This is essential. Pete Redrup

Josh Simmons – Flayed Corpse And Other Stories

(Fantagraphics)

The Furry Trap, Josh Simmons’ last horror anthology, is a superb book, nasty and genuinely scary in places. It’s a happy discovery to find that Flayed Corpse And Other Stories is a more than worthy successor. Even the most ardent Simmons completist in the UK is unlikely to have more than half the pieces here. Several are from the long out of print Habit 1 & 2, while The Cave is from Mirror Mirror II and there are numerous short strips from elsewhere. Often hard to come by the first time around, this is a great chance to get them all in large hardcover format.

Many of the stories here are collaborations, including his recent Twilight Of The Bat, his second and particularly savage entry in the Batman canon. There’s a thematic overlap with The Lego Batman Movie’s exploration of the relationship between Batman and The Joker, but this is not one for the kids. Sometimes the work here is gloriously nihilistic, but at other times an introspective melancholy can be found. Returning to The Cave, it stands out as a brilliantly paced comic: tension builds, is released by an anticlimax, followed by pure terror and then the withholding of visual information as the panels become black, leaving our imagination to do the rest. Standout piece Don’t Look Up plays with both our expectation of which character will be the cause of their own downfall and the physical format, with panels arranged in two vertical columns per page, wistfully coloured. There’s something in the faces of so many of his characters, a hardness, a resignation to the fates that inevitably follow, broken people about to be smashed to pieces for the last time.

This is exceptional value for money, a substantial collection full of hard to find work. It showcases Simmons’ ability to deliver completely satisfying short stories that are genuinely horrific. Sometimes this is achieved by withholding detail like the numerous black panels in The Cave, but he is equally capable of showing us it all. Frequently stories end with something terrible about to happen, leaving our imagination to suggest the rest. Whilst by no means the only practitioner of this technique, Simmons does this so well. I can’t imagine a better horror comic being released this year. Pete Redrup

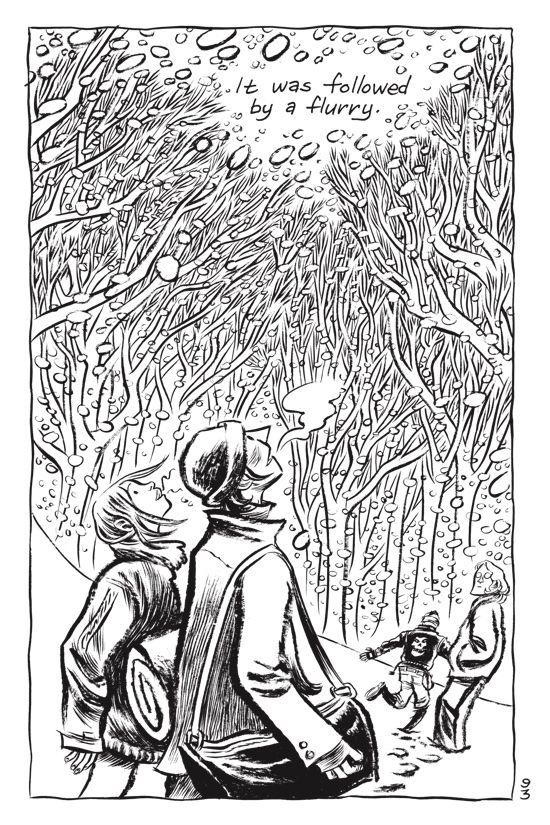

Craig Thompson – Blankets

(Faber & Faber)

I was persuaded to buy a copy of Blankets a long time ago by a display recommendation in Gosh! Comics, so it came as something of a surprise to discover that it has never had a UK release until this Faber edition. This enormous book (which, it should be noted, really deserves a hardback edition) must have taken forever to draw, but is the sort of thing you have to force yourself to slow down with, as the temptation is invariably to read it in a single sitting. If you’re not familiar with Blankets, it’s an autobiographical account of Thompson’s first love, as a shy, sensitive and very Christian teenager.

The artwork is transcendent throughout. He excels at woods and snow, and the trees in particular are quite beautiful. The way Thompson draws the different characters conveys much – bullies are shown with huge laughing mouths and thick necks, whereas he portrays himself more delicately, sensitive and vulnerable. Human nature is human nature and although pretty much everyone in the book is supposedly Christian there is a lot of unpleasant bullying. An early theme is his growing alienation. Being forced to spend time in a group with other Christians weakens his faith, and the more he’s told how he should be feeling the less he feels part of the group. However, Christian Camp improves immensely when he meets Raina. Before too long, he’s persuaded his parents to let him skip school for a fortnight and to drive him halfway to her house, where they meet up and he gets a lift the rest of the way.

As Raina’s father drives them to her house they steal glances at each other in the mirrors, through the gaps in the seat and so on. It’s very adolescent, but in a way that reminds of first love. It’s definitely self-indulgent, but what account of a shy, introverted teenager falling in love could be any other way and remain truthful? This relationship leads to some of the loveliest art in the book, such when Raina makes him a patchwork quilt and the segments become panels on the page that they are drawn in. Thompson makes the dreamy brushwork look effortless, so natural the way he does it. It’s black and white throughout, and yet when he and Raina part he still shows all colour leaving the world. When he’s absorbed in happy feelings, the backgrounds fill with swirled patterns, conveying that feeling of everything external dissolving away.

Although first love is the dominant narrative strand, darker issues also emerge: sexual abuse, treatment of disability and what happens if your sister marries a meathead. The book also serves as a reminder that while many Christians are fundamentally decent people, some of them tell children some pretty twisted stuff, absurdly and impossibly precise details about what heaven will be like or how sad their actions will make Jesus feel.

It may be indulgent, but whose first love story wouldn’t be? The art’s melodramatic backgrounds perfectly evokes the obsessive intensity of feeling those things for the first time, where the excitement of fitting together with someone obscures the imperfection of the fit, for a while, at least. By including a final chapter that encompasses many years after the first love, Thompson deftly sidesteps the risk of leaving the audience frustrated with his adolescent naïvety, and reminds us that we all move own from our immaturity, and that our experiences help us find the values we embrace in adulthood, whether that is to accept or reject. Pete Redrup

Nicola Streeten & Cath Tate – The Inking Woman

(Myriad Editions)

Should you be one of those ludicrous yet strangely common folk who believe that the only talent lies with that most oppressed of people, the white male, then you probably aren’t reading tQ, but The Spectator instead. You might encounter such views, however, and if so, this book contains ample evidence for the rebuttals you will feel obliged to make. The Inking Woman is replete with proof that much excellent cartooning has been produced by women in this country for over 250 years. Regular readers of this column will be well aware of the considerable talent evident in the small press scene, and indeed, such cartoonists are widely represented in this volume, including Hannah Berry, Danny Noble, Katriona Chapman, Kim Clements, Wallis Eates and Donya Todd, to list but a few.

The Inking Woman is a mixture of essays and mostly brief profiles of cartoonists. With the earliest work dating from the Eighteenth Century, there’s a substantial section on suffrage and a longer profile of the Victorian Marie Duval (about whom Myriad recently published a full length book). Much of the work covered here takes the form of political cartoons, decidedly left wing in outlook, many of which were most commonly seen in postcard form. In more recent developments, the rise of Laydeez Do Comics and recent increase in self-published, micro and small press work is given generous, and much deserved coverage.

As well as an excellent book to own, the gift-giving possibilities for the right wing misogynist in your family must not be underestimated. This is a fine and important work, documenting a substantial and sustained body of excellent cartooning of all forms. There can be very few people who would be familiar with all the creators included, and this strong selection will point readers towards much to enjoy. Pete Redrup

Tim Bird – The Great North Wood

(Avery Hill)

New from Avery Hill comes a pleasingly peaceful comic about the ancient and contemporary forests of South London; a comic all about the woods, without any green in it at all. Bird’s palette of warm oranges, pinks and muted blues creates a fantastical atmosphere that suits the mystical mood that permeates even illustrations of chicken shops and tower blocks as we follow an enigmatic city fox through the history of The Great North Wood.

In the 12th Century this forest covered the territory between Croydon and Deptford, diminished by increments ever since but still evident in the place names and stories of Norwood, Forest Hill, Honor Oak and all the rest. (it’s the North Wood, not the South Wood because it wasn’t named from London, because that wasn’t always the centre of the world). A small vestigial patch of forest still exists in Sydenham and this is what we must assume has inspired the author who loves to walk there. The facts are interesting enough and in places this reads like an illustrated history essay. But the path Tim Bird takes us on through these woods is a winding one, elliptical in places with satisfying call-backs and visual echoes, evoking the layers of the past, present and maybe future that overlap in transformed places. And ours is a transformed nation.

Britons and especially Londoners have perhaps the least visible connections to the wild places of our country’s past. This makes books like this all the more important, to remind us that once this was all trees. The old and the new intermingle here to neither’s detriment. You can have chicken shops and oak and ash and thorn, bus stops and fairies, old gods and new. Even in Croydon. Jenny Robins

Eleanor Crewes – The Times I Knew I Was Gay

(Good Comics)

The first 10 pages of this satisfyingly chunky little book first lived in zine form when Crewes first came out, to herself and those around her. So in a way, this is as much a testament to the power of self-publishing as self-actualisation. The title is delightfully obtuse, as we are presented with titbits of the artist’s life as she grows up unknowingly restricted by the heteronormative assumptions she has absorbed, we realise that this is not at all the familiar tale of a closeted teen burdened with self-knowledge and fear.

Navigating one’s own relation to the world has never been simple, but Crewes’ deftly drawn lines don’t divide her from the norm, they place her lovingly within its problematic embrace. The Times I Knew I Was Gay plots a very wiggly and fairly banal line through Eleanor Crewes’ life to date, which feels real without becoming bland. Essentially the point is she didn’t know she was gay. Or did she? No she didn’t. At least not consciously. She knew a lot of things though. What backpack she wanted to wear, the importance of baggy jeans, the joy of scary stories, of swimming under the sun, the bittersweet navigation of loving the culture you live within and building your identity from television, comics, religion, family, music, food, all the good things that aren’t sex.

As such this book is touchingly relatable, especially for children of the nineties. It’s tempting then to say that this isn’t a book about coming out, but it absolutely is. It’s about how that story is not the same for everyone, how sometimes we know exactly who we are and sometimes it takes a long time for us to realise we have to reframe that question. Also the drawings are super cute, and witty and poignant. I can’t wait to see what this new talent does next. Jenny Robins