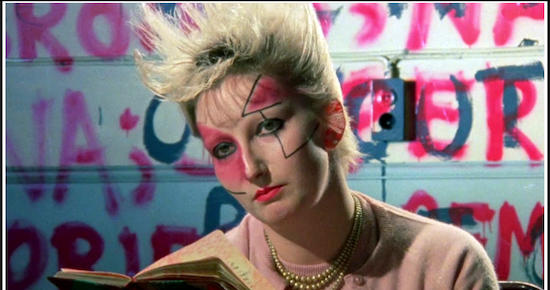

In 1973, four years before she was slapping on Mondrian-style face paint, managing and performing with an early incarnation of Adam and the Ants and starring in arty films directed by Derek Jarman, Jordan Mooney was Seaford-born Pamela Rooke, a shy but striking 18 year-old with a fetish for 50s clothes, ballet and Ziggy Stardust.

Her revamp proved to be an ever-evolving one. But integral to Rooke becoming the iconic Jordan we know today was a deep obsession she still has for reinvention, and a job that fell into her lap in late 1974 as an assistant in the infamous SEX boutique on the Kings Road ran by Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood.

Sporting thick black kohl eye makeup, split stockings and a peroxide-bright bee-hive, Mooney’s look alone, when she first crash-landed into London, was nothing short of shocking. She was hired for the shop on the spot and soon became as talked about as all the kinky clobber on the shop’s shelves.

Indeed, by early ‘76 and the first wave of punk rock, Westwood’s outrageous range of rubber, leather, muslin and mohair regalia could be seen not just hanging off Mooney, but on safety-pinned kids everywhere. She became a walking advert for SEX and a regular face at gigs by the Sex Pistols, the unbiddable band borne out of the shop and managed by McLaren.

Accompanying the Pistols on TV shows such as What’s On and So It Goes, Mooney would often find herself at the centre of the chaos, either topless onstage with Johnny Rotten at some private party or acting as punk spokesperson in interviews – all of which may have prompted her to move into managing and making music with Adam Ant, or acting for the late, great Derek Jarman in three of his films.

With its title taken from a line she uttered in Jarman’s Jubilee (or – alternatively – what her hair was doing through much of the ‘70s and ‘80s), Defying Gravity is Mooney’s rollercoaster ride through fashion, film, dance and some of the most explosive music of the era. With running commentary from the likes of Vivienne Westwood, Marco Pirroni, writer Jon Savage and ex-Pistol Paul Cook, it’s also a book she’s been requested to write ever since she pulled the plug on her punk exploits in the mid-80s and returned to her original coastal base to professionally care for cats.

What made you decide the time was now to tell your story?

Writing a memoir when you’re young is pointless because you want to have lived a life, and I wanted this book to be as complete as possible. But also there were some catalysts like me selling my clothes [from the era] and that wonderful exhibition on punk at the British Library. At the risk of sounding corny, that opened my eyes to the fact that people were still very interested in those times.

People had been extremely kind, coming up to me to tell me how meaningful my life has been to them. It’s not a big-headed thing me saying this, but it did make me think that if they are saying these things then maybe I should put it down in words and let people know about everything.

I always thought it was self-indulgent to do a book – and I have been asked two or three times over the years to write one – but then I realised that if I get people involved like I did it won’t be me just talking about myself, it will also be a social comment.

From a pink cape you wore as a toddler to the strong look you still rock today, you have an incredible memory for the tiniest detail of all the outfits, accessories and make-up you have worn over the years. Why have clothes and image always been important to you?

That is totally unexplainable, I don’t really know. All I know is when I was very little I wanted to dress in a particular way – and dancing, too, enabled me to become different people. I studied classical ballet and I did what they call character dancing and national dancing where you have different costumes from different countries. All of that became a great big way of expressing myself and I guess I took it from there.

I actually remember appearing on a Tony Wilson show [What’s On] and him asking me why I looked the way I do, and me turning around and saying, quite pretentiously, “Well, why did Picasso paint pictures?”

I wasn’t likening myself to this man but it’s all I could think of to say. I just had a vision which was perpetuated by the dancing. I’ve always wanted to express myself and turn myself into a painting or art piece.

So dancing played a profound part in your life. Had it not been for a car accident you were involved in when you were a teenager, would you say your ultimate ambition growing up would to have danced professionally?

I wanted to get to the Royal Ballet School and did audition for Sadler’s Wells, but people don’t realise how physically perfect, not just talented, you have to be. It’s like an extreme version of an MOT and you could be the most talented dancer in the world; if you don’t fit the mould of a ballet dancer you’re not going to get there. I loved dancing and was a particularly good classical ballet dancer but that’s different from being Royal Ballet material. I started as a little child upstairs on the landing with my mum’s scarves just dancing away.

Wearing the same tutu you later wore in Derek Jarman’s Jubilee?

Yes! Well, that particular one was bought for me when I was about sixteen and it was a major outgoing of money and I went to this place and got it made with this beautiful satin top. They probably don’t make tutus like that anymore. That was my pride and joy and I resurrected that. It was in a box in my cupboard along with my Venus t-shirt and it still had the feathers on it from that Jubilee scene.

You describe your childhood growing up in Seaford as “one long fantastic dream”. Was your move to London a scary one or would you say your experiences in Brighton’s gay club scene prepared you for all that unfold during at SEX?

It didn’t exactly prepare me, I was very comfortable going to those clubs. It changed my musical outlook as well and I already knew what I liked and what I didn’t like. Very early on, as a young teenager, I would hitch over to Brighton and hitch back again and it was a whole new world, really.

I wasn’t scared moving to London because I knew I wanted to do something and I was gonna do it. I first worked at Harrods, wearing green makeup, and I remember my mum saying to me before my interview for that job, “Do you think you’re gonna get the job looking like that?” She was dumbfounded when they called me back with a start date.

This is it, you had a striking look long before you met Vivienne and Malcolm, didn’t you?

Yes. In fact, Vivienne alludes to that in the book. She said she’d never seen anything like me. I was doing the DIY thing long before the punk style came along. I would go to second-hand shops and rip things to pieces. I’d pick up these beautiful American stilettos, these things that people didn’t buy so I had a really good choice of all these lovely shoes.

You mention DIY but did you not think the hefty price tags of Vivienne and Malcolm’s SEX range created a barrier between the well off and average kid on the street?

I so agree with what Vivienne says today and that is: buy well, buy wisely, and make it last. Yes, I still got stuff from charity shops and cut up my mum’s old fox fur and stuck it on the sleeves of a Maxicoat. I’ve always been the sort of person who would rather save up for something and have my heart racing in anticipation for something that I wanted. I’ve rarely bought for the sake of it.

There were a lot of monied people who would come into the shop to buy a look already made for them. Those were the people that myself, Vivienne, and Malcolm would question. What their motives were and do they look good in this? It was never a matter of getting a sale. It was about showing people that came in how versatile these clothes were.

Once you were working at SEX, how would you describe the change in vibe on the Kings Road as 1975 flipped over into ‘76?

The shop had gone through many incarnations before it was SEX and as Vivienne puts it in the book, there’s always been some mysticism about that plot of land at the end of Kings Road. There’s always been something there. It’s almost like some little magical place really and I liken it to those cafes philosophers used to have tea and talks in Prague or wherever. The shop was always the sort of place where you go and chew the fat.

Gradually the vibe did change. It got more publicity and more noticed and a lot of people came to do photo sessions. Of course, when the Pistols came along it all gelled together. But even before the Pistols there were lots of people in the know, people that were fascinated about what would be coming in next…

Many may be surprised to read that the whole rubber and leather fetish wear trend pre-dated punk and the formation of the Pistols. What attracted you to the fetish garb?

It wasn’t unlike how I was already dressing before I was able to buy latex. I was never part of any of the those clubs [the Rubber Duck club, the Wigan club], these people that wear those lovely rubber macs with canvas inside. They look a bit like SS Stormtrooper sort of macs. When rubber came into the shop and Vivienne found somebody that could make it easily, it was almost mirroring the little ballet practice skirt I used to wear and the leotard. I used to wear that a lot. Early on, I would walk down the street in tights and a leotard and this was mirrored in latex.

I loved the idea of these clothes not being behind closed doors and not being secret. I loved the feel of it when you walked. It was particular uncomfortable to wear for a long period of time and if it was cold weather it made you colder and if it was hot weather it made you hotter. So it wasn’t something easy to wear but I thought it was gorgeous. The only trouble is it perishes and none of it survived.

If Punk rock was two fingers to the music establishment, what would you say your look in ‘76–‘77 was a reaction to?

Before London, and even when I was at school, I was a loner. I never felt the need for anybody to sanction what I was doing. I wasn’t looking for acceptance. I wasn’t looking for anyone to like it. It was just something from my inner self. I suppose it was two fingers to the straightness of that time. Something we are going through again at the moment – everybody wearing the same style of trouser. And there’s no excuse for no colours being used! Why back then was everything taupe or beige or grey or diarrhoea-coloured really?

My look wasn’t a political look really but I remember being almost interrogated by a Russian journalist who couldn’t understand that this was fashion and not some major plot against the government. My political meaning was: I wanted people to be free. I wanted people not to feel fettered and held down by other people’s ideas of them.

Funnily enough nobody really copied me. I never saw anybody try to replicate my makeup or hair. When I say copy, I mean a direct copy. People would go to David Bowie concerts dressed as Ziggy and it was a direct copy but nobody did that with me. People looked at me and thought they could do their own thing.

In spite of its fantastic elements, do you think Jubilee succeeded in capturing the spirit of punk? Wasn’t punk, on the contrary, a notoriously sexless scene early on?

Absolutely. Sex was the last thing on people’s minds at that time. Dressing up and wearing make up was far more important than fucking really. It was almost like an androgynous time where men and women blurred the lines between each other. Men were still men and woman were still women but they weren’t stereotypical. This is why I think women were all of a sudden empowered to get up and play music. You didn’t have to dress in a particularly feminine way to get noticed anymore. It became an equal-level playing field that transmitted over to the music scene.

What do you think of the film when you watch it today?

The film has grown on me, actually, and I think more people get it now. The trouble was Derek [Jarman] was a very learned, artistic man – which was probably the antithesis of what most punks on the street were. They probably thought of him as an arty-farty poncey sort of bloke, so you’re already starting on the back foot.

I’ve done a few talks on Jubilee over the last couple of years and people’s opinions of it have rung loud bells in my head. Firstly, if you look at the film it’s mostly women who are empowered. They are the ones that go around killing people and causing fights. And it’s not gratuitous violence. It’s an interesting take on everything.

I always get the impression a lot of Jubilee was improvised.

Yes. If you watch the scene in which Adam [Ant] is pushed about by two guys dressed as policemen, that is real-life filming there. I had to intervene. Adam is not a drinker but the two guys that played those policemen were absolutely drunk as skunks and the pushing and shoving could have turned really nasty. You can see me pushing Adam down, away from them.

Adam thought the script was funny and the bit where he on the roof of the high-rise flats and the line is, “I never saw a flower until I was five”, he bursts out laughing. That laughter was real. He thought it was really naff and so his laughing set the other actors off laughing.

You starred alongside Adam Ant in the film and went on to manage an early incarnation of the Ants. What did you see in him and the band to make you want to take the reins of the group?

The first time I saw them was awful. It was all borrowed gear and things blew up and the gig lasted four songs or something. It was just down the road from the shop and Adam invited me because he wanted me to be the band’s manager. I went with a real keen eye to see what was behind this mask, really. He wore a leather mask and ripped up trousers. What I saw was an absolute diamond in the rough.. He was really really committed but everybody left. There was about five people left in this small room and everybody started moving backwards, away from the stage.

Why were you so against the dandy Prince Charming style and sound Adam and the band would later adopt?

Me and Adam have never fell out and will always remain great friends and if I ever needed him to help me in any way he would in a shot, but I really wanted the band to go into another realm, really. I understand why he did it but I personally didn’t like the young audience. The kids that would go see Adam and the Ants now had to have their mums and dads accompany them. I know that it made a lot of money for him and that he likes dressing up in character so I understand all the reasons he did it, but, for me, with all that talent he’s got, I wanted him to go in a different direction.

He did of course have great artistic freedom and nobody could quite grasp that this man had a vision and he knew what he wanted. He would argue with the record company till the cows came home about what the videos should look like and that’s why those videos were so groundbreaking. He knew what he wanted and he could storyboard it all. Everybody agrees that that band opened up the video market but that pantomime thing wasn’t for me, I couldn’t see it.

For me, one of powerful things about the book is that it uncovers a side of the punk story not revealed in any other books on the subject. You and Sid Vicious horse riding in Hyde Park and all the shenanigans at Buckingham Gate for instance. It must have felt like disembarking a speeding train when it all started to fall apart?

I got out of the scene for several reasons. I knew I couldn’t live that style of life anymore. It would have wore me out or worse killed me. I saw many of my friends die, like Johnny Thunders, Dee Dee Ramone, Sid [Vicious], of course, and I had a kind of survival instinct in me and that said to get away.

It was all turning New Romantic by then, too, and posing, which is fine, but that was all too over-egged and prissy for my liking.

A quote from Ted Polhemus in the book says “the essence and energy of punk was there before it had a name” but in your opinion when did punk begin to crumble? Would you agree with the idea that the early London scene died once it was labelled?

I think it lasted a lot longer than when it was first labelled. Certainly the Sex Pistols led the way but then they broke up. For me, Malcolm made a huge mistake taking them to America when he did. The Pistols did pass the baton on to some great bands though.

I guess the power of it all lies in ingenuity and some bands didn’t have the brilliance of a band like the Pistols. You can tell how committed somebody is by the way they wear things, how they walk, their stance. Take Adam on stage, or John Rotten with that hunched pose. He looked very comfortable and stood tall wearing that look. The Clash just wore boiler suits and splashed some paint about and I think that just legitimised the whole thing. I liked ‘White Riot’ but that’s about it

You moved back to your hometown and have auctioned most of the clothes that made you an icon of the punk era, do you ever yearn for a return to the crazy days or were these life decisions – and indeed the process of writing this book – a sort of closure on your punk past?

It’s not a closure and punk has been going on and will go on forever. There will always be artists, that will be ostracised for challenging the normal values of art and so I think what you are is what’s in your head. I still wear the clothes that I love and I remain open minded. You have to revel in your own identity.

Defying Gravity – Jordan’s Story by Jordan Mooney with Cathi Unsworth is published through Omnibus Press