Earlier this year, Fantagraphics released a beautiful edition of Joost Swarte’s collected work, Is That All There Is?. The title references the Dutch comics legend’s love of music (it’s an old Peggy Lee song) and shows his humble humour – as he says below, "there’s always more".

And indeed, comics only constitute part of Swarte’s oeuvre. He recently designed the Musée Hergé, has illustrated a number of covers for The New Yorker, founded both the Oog & Blik publishing house and Stripdagen comics festival (in his hometown of Haarlem), and, as Chris Ware points out in his excellent introduction, has even designed postage stamps and plans for pastries at his local bakery. Easy to see why he was awarded this year’s Marten Toonder Prize, a lifetime achievement award given to a cartoonist who has contributed to Dutch culture. And these contributions have reached far past the borders of The Netherlands. It was Joost (rhymes with ‘post’) who in 1977 coined the term ‘Ligne Clair’ (‘clear line’) to describe the incredibly influential style of Hergé and his compatriots, and of course Swarte’s own drawings. Although his work appeared in Art Spiegelman’s RAW magazine in the 80s, it is only now that the majority of the stories in Is That All There Is? have been translated into English for the first time.

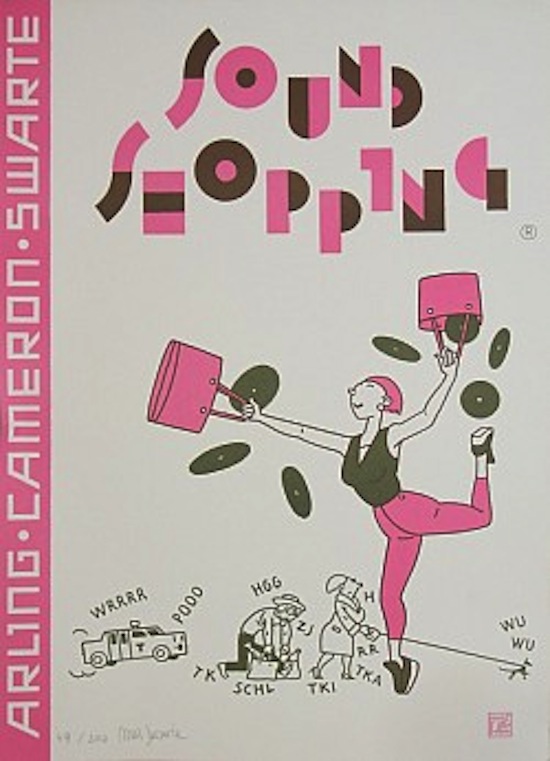

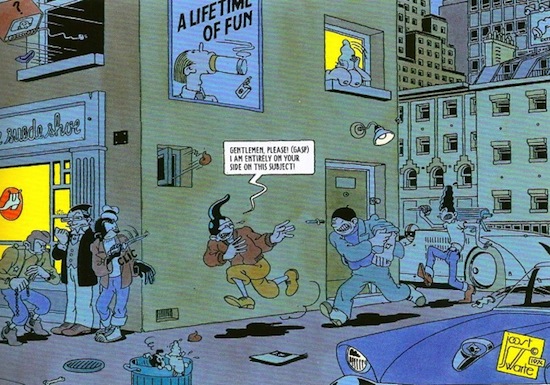

And these are works to behold, to marvel at their beauty and composition, all presented with a good sense of fun. The backgrounds brim with amusing and interesting details, the stories themselves bursting with mishaps, mayhem, music, and sex. One need not look past the front cover for evidence of all this – an ‘s’ for Swarte structured into two rooms flush with wonderful particulars, right down to the chef serving a dinner tray of copulating rabbits. Inside the book, Jopo de Pojo always seems to be meeting misfortune, especially whenever he tries to sing or in his variety of sexual encounters. We meet powerful criminals and petty crooks, are shown a story from Hergé’s past, and follow the antics of Anton Makassar, who even walks us through the colouring process. Swarte’s tribute to ‘The Incredible Upside Downs’ (strips that can be read two ways by turning the book on its head) is astonishingly good, his inspired word play in ‘An Apple A Day…’ is great fun, and The Mirror is downright beautiful. Across the middle of the book is ‘The End Times’, a newspaper written by his characters, concluding with ‘Listening Tips From The Studio by Joost Swarte’. A fantastic idea offering the curious fan a closer look into the artists’ life. An avid music lover, in addition to the impressive achievements listed above, Swarte has also designed many a record sleeve over the years. He’s even made a few albums himself, collaborating with Dutch musicians Fay Lovsky and Arling & Cameron, which we discuss below. Knighted by Queen Beatrix of The Netherlands in 2004, Joost Swarte is more than an incredibly talented and inventive artist, he’s also a gentleman and raconteur.

What have you been listening to today?

Joost Swarte: Two CDs came in today, both from Carel Kraayenhof, a Dutch bandoneón musician. He plays Argentine tango music. He’s quite famous, not only in the Netherlands for this, but also in Argentina, and he once played with Ástor Piazzolla on Broadway. The tango tradition here is the Argentine tradition, it’s not a ballroom tango, it’s something else. In the beginning of my career I made three record covers for Carel Kraayenhof and he called me yesterday and asked "do you want to come to the Amsterdam concert and present this new CD to me in front of the audience?’ So that is nice. The CD is good too, well done.

Yesterday I was listening to The Dr. Demento Show, from KMET FM Los Angeles. Old, old programs from 1974. A friend of mine, also a comic artist, made me a four CD set from that period with 176 songs and old material. Tom Lehrer and old cabaret-like things, full of fun stuff.

Speaking of old shows, I’ve been watching Van Oekel’s Discohoek on YouTube.

JS: Yeah, yeah, the Van Oekel show is bizarre. There was a comic story with that guy, do you know that? The Dutch comic artist, Theo Van Den Boogaard, made fantastic comic strips with Van Oekel. Check the Lambiek site, they have an enormous comiclopedia, and should have Theo Van Den Boogaard. This Van Oekel show was written by a Dutch artist called Wim Schippers. He always does something that nobody understands. One of his early works was Peanut Butter Platform, one centimetre high on the floor of a museum, which made the whole place smell like peanut butter. Last year he sold the concept to Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. This man wrote the scenarios for the Van Oekel television shows but also for the comics. Another crazy project by him is a theatre play with no actors and actresses, no humans at all on the stage, only dogs (laughs) [Going To The Dogs]. I went to the play. It was a crazy story and they manipulated the dogs with food at the side of the stage. But after a while the dogs were fed up with all this food and didn’t want to walk anymore so they’d just piss in a corner or sit around. The whole theatre was full of Wim Schipper’s friends, we had a fantastic evening.

But yeah, Van Oekel was a bizarre show. Donna Summer was on the show a few times, and there was one episode where you saw Van Oekel vomiting into the bicycle bag of one of his employees, just for fun. It was bizarre.

I watched that video of you performing ‘Yawn Blues’ and ‘Appellation Contrôlée’ at the comics festival. (Les Rencontres Chaland, October 2010). That’s a really catchy song.

JS: It was a little tune that I often sang while doing the dishes after dinner. And when I started the project with Fay Lovsky, I sang it to her and she said "wow, that’s a good tune, I’ll make a composition out of it". And some years later, a friend of mine took this CD along with him to a studio in France, where they were filming a cooking program, and the cook of this show said, "this is gonna be my song’. Then for two years, three days a week, it was on national television in France. That was great.

You wrote a couple of songs with Arling & Cameron too, right?

JS: That’s another one. They’re both good guys, it was fantastic. I learned about them from the Pizzicato Five. I bought Happy End Of The World when it came out and on ‘Arigato, We Love You’ there’s a telephone conversation between the singer of the Pizzicato Five and Richard Cameron deciding to make a song together. That was a funny little thing, but I was wondering "who are these guys from Amsterdam?" I never heard of them but they had already made several records for the club circuits, really dancey things, quite good. For our album, I wrote letters to them in which I proposed concepts for songs. So I am co-composer for some of the songs on Sound Shopping. They sampled a lot of material for that record and all the samples came from my record collection. That was a fun project also. It’s almost the same as with the project with Fay Lovsky, there was a movie in the United States that wanted to use one of the songs and fortunately I was co-composer of the song.

That’s an interesting way to work, suggesting ideas for songs.

JS: Yeah, yeah, I thought it would be nice. For instance, I thought of the idea for a song where a girl talks about what an awful nightmare she had but then the tune would be very positive and up-tempo. This contradiction in a song is something that appeals to me a lot.

Do you play any instruments yourself?

JS: [low voice] No, no [laughs]. Of course I would’ve liked to but… With friends I had a pop group called The Shark. I think I did two concerts with The Shark and then I learned that if I want to sing better I had to practice, and composing takes a lot of time, and I thought maybe it’s better that somebody else does it and I concentrated on my artwork. That was the decision.

Your publishing company, Oog & Blik, put out the Jopo In Mono album.

JS: Yeah. Well, the co-founder of Oog & Blik publishing house is my friend Hansje Joustra. We first met a long time ago when he still worked in a record store and imported American pop music. He asked me to make advertisements with artwork for the shop. After this he also had his record label No Fun, in the punk period, and I did several record covers for him. Then he transformed it into another label called Torso, which did Dutch avant-garde music and new wave, more the music for the students of the art academies. Mecano was one of the groups on this record label. That was a quite interesting period. And then at a certain moment he decided to have a comics shop and I said "would you like to do imports?" Because my books were often published in France before they were published in Holland, I needed somebody to import my book from France to Holland and he said "let me do the job". So he started a distribution firm for comics and at a certain time we decided to start a new thing together which was Oog & Blik publishing house. Two years ago we sold it to a major literary company in Amsterdam, so my friend Hansje Joustra now works in this literary firm and I am still advisor for the company.

Jopo In Mono came out in 1992. And that was just because I wrote a letter to Fay Lovsky. I loved the music that she made, and she had some very good records out. There was a documentary on Dutch television in which she was very sad about her last project, The Magnificent Seven, collapsing. They were a group in the late-80s who made film music and amusement music from the 50s, like the compositions of Leroy Anderson and Carl Stalling. And when I saw Fay on the television very sad that this was over, I thought "maybe it’s an opportunity to have a new goal in her musical career, why not write her and propose working together on a project". And she accepted. She knew my work, and was a fan of it, so that’s why my characters Jopo and Anton Makassar got involved in this. I sang on two tunes on the CD and became the co-composer of ‘Appellation Contrôlée’. That was an interesting project, I would love to do it again.

The most recent musical project I was involved in was called Strips In Stereo. A Dutch publisher made a comic book with a CD, and in the comic book about 25 comic artists interpreted a famous Dutch pop music tune. I did the story for a Leon Giesen song and it’s also in Is That All There Is? ‘Bare-Assed And Bald’ is the translation of the title, ‘Naakt en Kaal’. He is a nice musician, he has all these very, very special ideas for the text of his songs. So it helps if you know the lyrics, cause he’s one of the best.

Where did the character of Jopo come from? Things never seem to go right for him when he starts to sing.

JS: There was a period in the beginning of my career when I was looking for new characters and I tried several out on a sheet. What I thought was very important is that while you can recognize a character from their body and clothes if seen from head to toe in a panel, you should be able to recognize the character if you see only their head. And I thought I would do something with the head like I saw in the Marx Brothers films. The Marx Brothers they all have similar sorts of faces but Chico always wears a hat and Harpo always has blond curls and Groucho has a moustache. You can recognize them easily. I played with elements on the head so I had one character with a tin can on the head like the Happy Hooligan, the old newspaper comic in America, and I played a little with hairdos and one of them was Jopo. Some of the other ideas went into the group of three anarchist comic characters called The Trio Interessant (The Bros Interessimo). They’re also in Is That All There Is? You can find them in a one-page comic and they also play a role in the ‘Imago Moderna’ story with Jopo de Pojo.

So that was the first idea but then for Jopo’s clothing I thought his character was somebody who doesn’t control his own life, who is always the victim of circumstances, sort of a cliché type. If I take elements from other characters, so he doesn’t have any strong personality, that would help to show something of what he doesn’t have. So the golf pants are from Tintin, and you see on his blouse there is a sign that comes from Krazy Kat, and his head in fact has to do with the musical note the eighth note. If you take the stick out and put the flag directly on the head then you have Jopo’s head. But he was also a bit inspired by old Disney things. The Little Animal comic strip by Walt Disney or the older Felix The Cat sort of faces, there is also something of that period in his head. He’s a mixed up guy.

So are you a big blues fan? With mentions of Albert King, Fats Domino…

JS: Oh yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Albert King’s ‘I’ll Play The Blues For You’ is one of my favourite blues songs so I thought it would be nice to give honour to him with this comic strip. I started with blues but then I learned that a lot of musical styles come from New Orleans so my interests got more and more into New Orleans Rhythm & Blues. The old Professor Longhair and Ernie K-Doe, the Neville Brothers of course, all sorts of artists. And Allen Toussaint, who was a good producer there. There’s so many interesting groups in New Orleans so I was really attracted to that.

I remember when I was about 15/16 years old, Slim Harpo was one of my heroes. I really love his stuff. When I was with my fellow students in Paris in the late 60s, there was a concert by Otis Redding so I saw a whole bunch of American artists there. That was fantastic. The concert was part of the Stax/Volt tour. You had Otis Redding, Carla Thomas, Sam & Dave, ‘Knock On Wood’ Eddie Floyd, Arthur Conley, and the band was Booker T. & the M.G.’s. That was a fantastic line-up, incredible. I couldn’t sleep at night.

In Is That All There Is? you mention being enticed by beautiful record covers (‘That Second-Line Beat Is Rather Neat’). I always have that problem, if I see a really good record sleeve I will buy the album even if I don’t know what it sounds like. What are some of your favourite record sleeves?

JS: Hmm… let’s see… well, some are quite bizarre, I have here in my hand the Jackie Gleason Orchestra’s Music For Lovers Only. That’s a nice cover, a photograph of two empty glasses and you see a lady’s bag and her gloves and two cigarettes in an ashtray and that’s it. They’re probably somewhere else, that’s what the photograph means to say, and it’s called (breathy voice) Music For Lovers Only [laughs]. There was quite a good cover for Malcolm McLaren’s record [flips through albums], quite interesting, with the Keith Haring thing on it [Duck Rock]. I think the most interesting covers I have here are often American pressings, the old ones with a lot of cardboard involved, solid sleeves, those are nice. And I have here one of Robert Crumb’s called Please Warm My Weiner, which is an old record. That’s quite a good one.

You put out a record of his, right? Or of his favourite songs?

JS: Yeah, that’s right. Oog & Blik did. My friend Joustra came up with the idea of putting all of Robert’s material together in a book called The Record Cover Collection. And to accompany a deluxe edition of this book Robert collected his favourite songs and we made a record of them. The book was recently redone and I did the graphic design for the first issue and also for the recent one. The book is now called The Complete Record Cover Collection, although it’s never complete I guess. The American publisher wanted this title The Complete Record Cover Collection; I prefer something like Is That All There Is? I know there’s always more, there’s always more. But Robert Crumb’s an enormous record collector. His period is more the 30s, and he only collects 78s. I think he has between three and four thousand 78s. But he’s really, really a collector. He files them perfectly and keeps them in mint condition. Yeah, that’s fantastic.

What was it like working on the Musée Hergé?

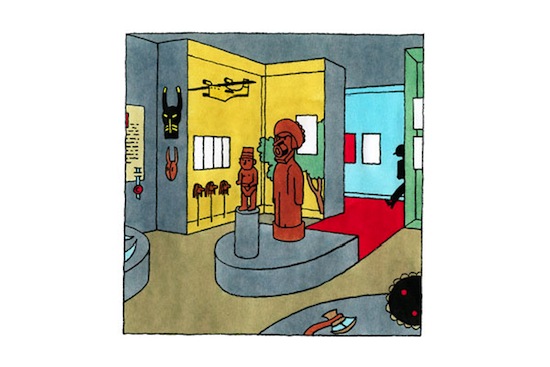

JS: That was very, very special. In the year 2000, as a founder of the comic festival here in Haarlem, the Frans Hals museum asked me to design a Tintin exhibition. So I went to Brussels to negotiate and discuss with Nick Rodwell, who is the second husband of Fanny Vlamynck, Hergé’s widow. He and Fanny were very enthusiastic about the installations and they liked the exhibition very much. We had a fantastic show with more than 30 original pages from The Blue Lotus. They allowed me to use the Le Petit Vingtième covers from their collection, that’s the magazine in which the book had first been published, and we told the story in a series of posters. It was quite educational, it was graphically nice, and they liked it a lot and that’s the reason why they asked me later to work on the Hergé Museum. And that was quite an interesting job. I formed a group of three with Philippe Goddin, the official biographer who made these beautiful volumes of the catalogue of Hergé’s work, and Thierry Groensteen, the director of the comic museum in Angoulême, France. So we had somebody who knew everything from the collection, we had somebody with museum experience, and me as director of the team and the designer of the exhibitions. We decided how many rooms there should be, exactly what we should show, I also made drawings for this, and what technical things we’d need and all this went to the architect, Christian de Portzamparc, in Paris and he made the museum after our specifications. And then came the task of finally deciding how these rooms would be filled.

One of the most important things I advised was that the difference between a museum and a comic book is quite huge. A comic book you read one-to-one: there is the comic artist and there is the reader and it feels quite close. If you read a comic book you jump into the drawings. And in a museum you have them on a wall and you know that to your left and right there are other people looking at the same drawing, so there’s more distance and also the feel of "how should I relate to these other viewers". So I preferred to show the work more in flat show windows, vitrine tables, so that you can look like in a book. What we also did was have work selected for three exhibitions, because if an original ink on paper work is shown to the light, then the quality of the paper and the ink will deteriorate over time. We use low light in the rooms, because the human eye easily adapts to it, but as a security measure, after four months an exhibit goes back to the cellars, in the vaults, and another parallel exhibition is shown which tells more or less the same things about the works of Hergé.

We wanted to make one of the rooms the ‘Museum of Foreign Cultures’, and we tried to get hold of elements from Africa, from South America, the countries where Tintin went to, but it wasn’t possible to borrow these for any length of time. So we only show material from Hergé’s own collection, from what he had in his house. There is a museum in Brussels that has the fetish of the Arumbaya Indians from South America and also the mummy of Rascar Capac. They let us come with a photographer and make 3D photos of these statues and we blew them up to life-size. I then asked the architect to design fake doors where instead of entering a room, there is this large photograph with Rascar Capac or a huge Arumbaya fetish. And if you have 3D glasses on, which are of course given in this room, you see it as if it’s really there. So that was fun to involve in the presentation.

I remember as a young kid when I read the Tintin books, it was like he took you with him to these foreign cultures. We now have Google and can have the whole world on your desk top, but at that time it was a hidden world and it was something of a sensation that Tintin showed you something of the South Americas or whatever country he was in, like Egypt, Asia, China. So I found a collector who has a huge collection of stereo photographs from the first part of the 20th century and we selected stereo photos of Shanghai at the time of The Blue Lotus, and photos from Egypt with the pyramids, and also Tibet. I ordered some viewers to see these with so you can jump into the other cultures and these old black and white stereo photos are marvellous, it’s almost like being there! So that helps to make a sensation for the visitors. So go there [laughs].