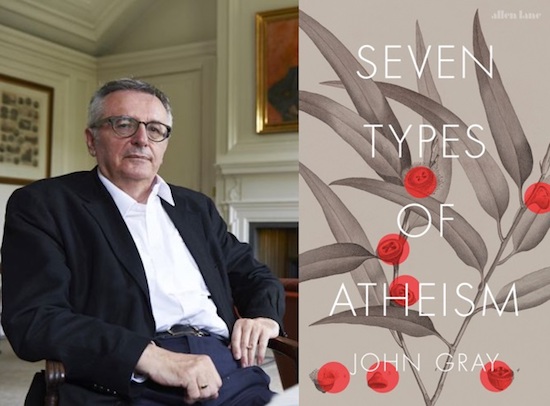

In 2002, John Gray published one of the most remarkable books of the century so far. Straw Dogs arrived like a hand grenade rolled beneath the corpulent bulk of mainstream liberal views on progress, human destiny, and secular Western values. Since then, he has written several books dissecting contemporary ideas about capitalism, free will, mortality, science, and our place within the animal world. His intent, nearly always, has been to expose the extent to which they are based on delusion, myths, and a false sense of exceptionality.

No less so with his latest book Seven Types of Atheism, in which Gray explores the various manifestations that the rejection, disavowal, or hatred of religion has taken over many centuries. Very often, he argues, the bonds between religion and atheism are more closely interwoven than we might have thought.

But if you are expecting a demolition job on the ‘New Atheists’, such as Richard Dawkins and co., then be ready for disappointment. He glosses over them in the first chapter. But the book is nonetheless rich. In typical Gray style it barrels at speed from one subject to another – from Ayn Rand to The Brothers Karamazov, from transhumanism to the negative theology of Arthur Schopenhauer.

Michael Brooks sat down with John Gray to talk about the book, the “incurably irrational” liberal mind, and the “pernicious bullshit” of Steven Pinker.

In your introduction, you say that you are drawn to the types of atheism that revolve around the rejection of a ‘creator-god’ without humanism, as well as those to do with an unnameable yet mystical god. You’ve changed political positions quite dramatically over your career – has that been the same spiritually? Have you held more trenchant atheist views or more religious views at different points in your life?

No, I’ve never been a practitioner of any religion and I’ve always called myself an atheist. The core of my book is the claim that the choice between atheism and religion isn’t binary because they aren’t two separate mutually exclusive things. There are many different types of atheism, including atheist religions like Buddhism and Taoism, and there are types of atheism that come close to mystical religion in other ways by postulating an unnameable reality.

Politically, the view I’ve always held and expressed is that politics isn’t a practice that should be governed by an ideology or a project of emancipation; politics is the practical business of finding partial remedies for recurring ills.

One of my first widely-read publications was an article I wrote in 1989 where I said that, contrary to popular belief at the time, the collapse of Communism in Russia would result in a normal resumption of history. People called this apocalyptic, and yet they were the same thinkers promoting the idea that it was the ‘end of history’. That had a huge impact on my thinking and I concluded then, and still believe now, that the western liberal mind is basically incurably irrational and unrealistic.

When I first heard you were publishing a book about atheism I was expecting more of a dissection of the New Atheists.

Yes, I was toying with the idea of not including them at all. A few friends who I spoke to about it said “oh yes, great idea”, but then I thought it wouldn’t be fair and would make the book odd because most of its readers will be most familiar with those atheists and may have wondered why I hadn’t mentioned them.

That said, you dismiss them within the first chapter, describing it as a ‘closed system of thought … best appreciated as a type of entertainment’. The thrust of your criticism seems to be that Richard Dawkins, for example, sees science as an unquestioned view of the world (an ‘unalterable truth’).

But in The God Delusion, Dawkins is at pains to stress that he is examining religion and belief in God as a scientist would any other theory. He concedes that he cannot be absolutely sure God does not exist, or that the theory of evolution is true; just that the weight of the currently available scientific evidence would tend to lean towards those verdicts.

The error is to think of religion as a theory. Dawkins thinks of religions as obsolete theories of everything, and that we’ve now got a scientific view of the world which achieves what religion set out to achieve. He’s reacting to a tradition within Christian theology. But as an account of religion, Christianity is only one among several and there are many branches and traditions in Christianity. The example I give in the book of this misunderstanding is that the Genesis story isn’t an early attempt to do what Darwin did in The Origin of Species. If you go back to the Jewish scholars, they are quite explicit about it not being intended as an account of human origins. It was a myth.

I believe myths are complex structures and narratives, the role of which is to give meaning to human life. Religions are not in general falsifiable theory. However, there are certainly elements of historic Christianity which do make claims that are falsifiable. In other religions such as Judaism, Hinduism, or Buddhism, all kinds of fantastic things and miracles happen, but the truth of the religion doesn’t depend on them, whereas Christians have pretty much always made the credibility of their religion depend on Jesus coming back from the dead, and that sort of thing. In my view, the real criticism of Christianity doesn’t come from science but from history. If it were to be proved that there were in fact four different Jesuses living at different times and only one of them was crucified, for example, I think Christianity would be seriously compromised. In the book I paraphrase Wittgenstein that you could explain everything and still the need for meaning would remain.

Whenever I go and visit my grandfather I sometimes go along to his local church service and am struck by the poor attendance and conspicuous absence of anyone under the age of about 70. You assert in your conclusion that religion is thriving and traditional faiths re-emerging. But is this true of the Christian west, which statistics suggest is suffering a terminal decline (just 3% of 18–24 year-olds are members of the Church of England), or do you foresee a resurgence in the near future, perhaps taking on different forms from traditional church attendance?

Some traditional religions are expanding, Islam for example. In South Korea there are now more Christians than so-called indigenous religions. In China there is a huge underground conversion to Christianity. Some people speculate that a few years from now it will be the largest Christian country in the world.

Globally it goes in many waves, I don’t think the relative weakness or near-disappearance of traditional religion in Western Europe is borne out everywhere. It isn’t in America, for example. Maybe in 100 years it’ll be different, but it is roughly the same now, in terms of the depth, scope and intensity of religious belief, as it was when [Alexis] De Tocqueville went there in the 1830s. He said when he moved from Canada into America he stepped into a world of sectarians. And they’re still like that, compared with Europe.

I don’t think there’s any reason to think that America or other parts of the world will repeat the experience of Europe, or that Europe will stay as it is. Fifty years from now, a new religion may have emerged, or some new forms of old religions may be making big in-roads. It could be that there will be treatment of religion as essentially a kind of therapy – ‘it makes me happier, I can work better, makes me less anxious, more sexually attractive’, or whatever. You could argue religion has always offered this, but it’s not strictly true. Traditional religion, especially Christianity, makes much of the ‘dark night of the soul’, or mental traumas that believers go through – not just from fear of Hell, but of being punished by God. So, it’s not meant to make people happy all the time like a universal Prozac, but believers may be fine with that being the price of it.

You write in the book that “religion is a powerful expression of human imagination”. Isn’t the problem that as much as the human imagination is capable of investing in belief systems, such as Mormonism, Kabbalah, Scientology, these are used very often as a means to exploit people emotionally, often financially, sometimes even physically? Is the religious impulse too easily exploited by the equally powerful human impulse of greed?

Yes, but it’s a completely universal problem in that many secular systems are the same. The cult of EST [Erhard Seminars Training] in the 1970s, for example, or fashion, diet books, or whatever. These all show that there is an enormous need, widely dispersed in the population, for techniques of self-help, and we are all open to exploitation.

There have been many other senses in which religion has been exploitative. It’s often, but not always, aligned itself with the power structures in society and propped up the social order by saying it’s divinely ordained. It’s a bit like saying religion has caused enormous suffering, and so it has. But so has the pursuit of knowledge. What’s special about the crimes of religion, just because it’s not true? A lot of what was represented as science is not true. As I discuss in the book, in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, there were a whole range of thinkers who believed in what they called scientific racism, who did terrible harm by legitimating some of the worst crimes in human history. It can be called bad science, but it wasn’t rejected for being so. It was rejected because the horrors it enacted in practice were revealed.

My general theory is that religion is more like art than science, it’s a great work of human imagination. But, like every great good, it comes with evils attached.

There seems to be a resurgent interest within pop culture in nihilism and philosophical pessimism – writers like Emil Cioran and Eugene Thacker being referenced by the makers of True Detective, for instance. Do you think this is linked to the realisation that with the last thirty-plus years of neoliberal economics, the idea of inexorable progress has somewhat hit the buffers?

There’s certainly a link, but it isn’t really the inexorability that’s the point. If you suggest to people now that ethical progress, in the sense which they take for granted, is impossible, they don’t understand it. Even very intelligent people will say they think it’s about inevitability or perfection. What it’s really about, this idea of progress, is an accumulation of what has been achieved before.

If you look at views of history and the human world that existed before this view came about in Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, or look right back to pre-Christianity, or Buddhism, Hinduism, or some Chinese thinking, all will recognise long periods of improvement, more civilisation, art, wealth, better institutions and government, but they all thought that what is gained will be lost. Whereas, pretty much everyone now believes that what has been gained cannot be lost.

Look around the world, many of the gains of which we in the West and elsewhere are rightly proud have been reversed in recent years. Thirty-six Commonwealth countries have made being gay a criminal offence. Russia has moved away from a short period of tolerance to being more persecutory. The Middle East has become much less tolerant with the rise of Isis and before them Al Qaeda. Even in America, there are states trying to reverse laws on same-sex marriage, and so on. In the ancient world, there was no real conception of homosexuality, it was just what people did at various times; there was a two thousand-year period of regression followed by a couple of generations of genuine advance.

Different examples would be the reintroduction of torture – not on a mass scale, but it was widespread in Iraq. Also, it would have been hard to imagine targeted attacks on Jewish people taking place in European cities even ten years ago. It’s horrific that anti-Semitism is coming back, but I’m not totally surprised because evils like that do come back. The correct attitude is one of unyielding stoicism – not in the sense of resignation or inaction – but in never imagining that they are gone completely. What goes against this is the accumulative idea of progress that thinks, ‘we’ve solved that, we’ve improved the position of women or gays, now we can move on’.

This is the aspect of my thinking that people find the most unsettling, because it suggests that progress isn’t always possible. Solitary acts of courage and kindness are always possible because they are etched in human beings along with cruelty and many other things. That’s not to say I don’t think things can improve, because evidently some things do – emancipation of women, anaesthetic dentistry, or contraception. But not the internet, and definitely not Facebook or Google – not even the telegraph. Most of the big technological advances have been double-edged.

This is painful for some people to accept because they fall back on beliefs which always assume a monotheistic view of history: progress is always possible – when they actually mean redemption is always possible. For people to understand the flaws in the idea of progress, they’d have to be more intelligent than their theory of progress says that they are. In other words, for there to be a wide understanding of what’s wrong with the idea of progress, it would have to be false.

I would love to see you in a public debate with someone who you’ve had a fairly heated academic feud with in recent years, Steven Pinker. He seems to be on a mission to try and reassure liberals – whose faith has been hit by Brexit, Trump, and the resurgence of the left in British politics – that Enlightenment values are as strong as ever and progress is continuing apace. On what basis do you think he’s misguided in this endeavour?

The book that alarmed me first was The Better Angels of Our Nature, but his new one Enlightenment Now alarmed me even more. I think his increasing popularity is to do with the feeling of insecurity and the need to feel reassured. To be fair to him, he’s open about the fact that he likes free market capitalism, and what he wants is a universal version of the most unrestricted type of American capitalism. But the paradox is that an unreconstructed market liberal can be so popular among the left. It’s bizarre.

The view of his that I really detest is the way he represents war as a sign of backward culture. Look at the terrible wars that raged in South-East Asia from the 1940s to the Vietnam War – were they the product of the backwardness of those civilisations? Or was it more to do with Japan in the Second World War followed by the French occupation and then the American occupation? Many of the wars of the twentieth century were colonial or neo-colonial or had to do with imposing terrible ideologies.

I find that view to be poisonous, pernicious bullshit. The danger of Pinker’s thinking on progress is that you stop caring about casualties of those ‘backward’ civilisations. It’s the same thing the Maoists said about Tibet, and around a quarter or a third of the population perished. Is that okay because they were superstitious, medieval people? I reject that categorically, and that’s one of the sources of my ire against Pinker. Philosophies of history are generally rationalisations for mass murder – ‘it was terrible all those people dying, but still, it was an advance…’

John Gray, Seven Types of Atheism is published by Allen Lane. Michael Brooks runs the Alt-Classic Album Playback series of vinyl listening events in London