It begins with my older brother, Colin, who enjoys science fiction, the symphonies of Gustav

Mahler, and who has always carried about him a casual sadism.

One night in the early 90s when we were kids, Colin waited until the lights went out and

said, “You know what?”

And I said, “What?”

“Have you ever tried finding that exact moment when you stop being awake and start being

asleep?”

“Nope.”

“Well you should because when you die it’s going to be the same thing.”

I sat up in my bed. “No it won’t.”

“Yes it will,” he said. And soon he was asleep, and I was not.

At one time, I thought I could find that moment between consciousness and sleep, and

conquer it. Only you can’t tell exactly at which point you’re falling asleep just like you can’t

tell at which degree water burns skin. It’s just different types of heat until you tear your

hand away, swearing. Since then, pardoning physical exhaustion or drunkenness, I’ve had

problems getting to sleep, because I keep thinking I’m going to die.

But it doesn’t make much sense for a kid to think about dying. In every other part of my life,

I was bang my head on cement stupid; I didn’t even wear a bike helmet. Still, on the way

to Catholic school, I strolled past the casket factory. So I’m always seeing this deathbox

warehouse with its sparks and smoke roar. And I’m spending my formative years at a school

that rules with a crucifix heart. It’s the type of learning institution that’s got a vampire lust

for phrases like Most Precious Blood gouged into concrete and an agonized Jesus bleeding

eternally in every room.

*

I’m up at 4 a.m., I get five hours of sleep, and now it’s time for breakfast. I crack two eggs,

slip one yolk into the trash, pour the coffee. It’s still dark out. I don’t care for that a bit. I

pepper the eggs and slouch near the space heater and review my notes for the day.

If I look outside my window, I’ll see that my elderly neighbor and fellow early riser, Ms.

Ruiz, has already thrown cheerios, spaghetti noodles, and bread onto the square of sidewalk

beneath her window for the pigeons and rats to breakfast on.

*

Sleep is the brother of death, at least according to the Greeks, who seemed to know all things

first.

Hypnos and Thanatos were their names. They were twin brothers. Do you think they got

along well? In the painting by John William Waterhouse, “Sleep and his Half-brother

Death,” they’re drowsing on a Mediterranean couch, Death in the shade, Sleep in the light,

and Sleep’s just got some poppies loose in his hand. Anyone could pass by and steal those

poppies. The two have the unconscious glow and platonic affection of children, androgynous

and with hands slung around each other.

Was one ever mistaken for the other during significant moments? Doesn’t it seem unfair

that something so pleasant as sleep has to be akin to something so presumably unpleasant as

death?

*

That I keep thinking I’m going to die any evening now seems stupid, or at least unlikely—

young white men don’t often die in their sleep. Young white men probably have the lowest

mortality rate on the planet, probably at the expense of everyone else’s increased mortality.

And anyhow, of course I’m going to die. Thing is, it’s inconvenient to think about death all

day with the rising dreads at night.

So when I was about seven, I would sigh and moan lowly to myself until I couldn’t think and

left my bed to meet my mom in the kitchen. She chain-smoked by oven light. Between the

two of us and ecclesial smoke twirls, we agreed death was unfair and the best thing was to try

not to think about it. And pray and be nice to people. Goodnight.

Because it seems like bad manners, I stopped sighing in bed, but I started tooth grinding, and

all because of the clock tick of death that my brother set off in me.

*

My friend Natalia is deeply spiritual. And religious, too, which is to say she follows the

rules and enters church buildings on a regular basis. Natalia also has more nightmares than

anyone I’ve ever met. They are largely apocalyptic and involve invading alien forces and

vast destruction, and this from the mind of a woman who does not watch TV or the movies.

Natalia tells me that at the climax of her nightmares there is the feeling that she has been

ripped off and the investment in God seems poorly planned. But in the morning, she weighs

terror against love and chooses to stay with belief.

One recalls Psalms: “You will not fear the terror of the night, nor the arrow that flies by day.”

One recalls Proverbs: “If you lie down, you will not be afraid; when you lie down, your sleep

will be sweet.” Who among us inhabits the relaxed “you” of these aphorisms?

Valiant Natalia – Driver of cars/strummer of guitars! Coax me toward accepting my death!

*

When I was old enough to know better, we were in Theology class at St. Rita HS, and I

learned that long ago God switched from a system of works to a system of faith. And I

thought, I am fucked, and folded my hands over my eyes.

I went to confession that month and explained my situation to a priest through a screen. “I’m

a nice guy, mostly, but I don’t know if I believe in God.”

“How can you see a sunrise and not believe in God?” asked the priest.

And I thought, You are not helping me.

And then ten years later there’s Natalia, and she’s telling me that I have a unique moment,

that I have more in common with six billion people than anyone else who has died before

me. “Think of all that we have in common!” she says.

*

Sleep has been afflicted for centuries, and not only in the realm of the material world.

Civilization has long suffered under the incubus, a monster that rests on the bodies of

sleepers.

“Incubus” appears around 1200, meaning “nightmare, one who lies down on [the

sleeper].” “Nightmare” appears in the late 13th century as “an evil female spirit afflicting

sleepers with a feeling of suffocation,” with “Sense of ‘any bad dream’ first recorded 1829;

that of ‘very distressing experience’ is from 1831.”

The word “Incubate” appears later in the 1640s, meaning “To brood upon, watch jealously.”

In 1721 it appears as “to sit on eggs to hatch them,” or “to lie in or upon.”

My double bed is an incubator for dark thinking.

*

There was a year when my death watching became unbearable; I’m going to say 2007, when

I was 22. Gray thunder of oceans reminded me of death. Washington Square with jugglers

and Manhattan trees and jumbo pretzels reminded me of death. The activists I lived with,

monastic, dumpstering bagels & watching genocide documentaries full-screened on the

computer—they especially made me think about dying.

At 22 I worked around the philosophy section of the university library, second floor north

east corner, where people go to get nothing done. It’s the meeting place of the Librarian

Chess Club, where weary shelvers congregate to drink Crown Royal on the sly, and play a

little chess.

While I read a line, “And when you look for a long time into an abyss, the abyss also looks

into you,” Charlie my coworker was a table over, stretching his arms to me. “Jimmy, put

down the books,” he unstacked some Dixie cups, filled one halfway. “Play some of this chess

with us.”

*

At 22, each day became a black t-shirt day. When my friend Monica left her black nail polish

on the coffee table in our apartment, it went to use.

At the coffee shop, I drew skulls and ghosts all over receipt paper and coffee cups. My boss

asked what the hell was my problem. I told him I was in a gang and this was the only way to

get new members.

He didn’t bat an eye. “Good,” he said, “maybe they can teach you to be more disciplined.

You forgot to take out the garbage last night.”

Next day at work, in the back office I saw a bottle of nail polish remover resting on top of a

five-dollar bill. The bill and bottle each bore a message in black Sharpie. “HAIRCUT,” said

the bill. “NO MORE CRYIN,” said the bottle.

*

Public Service Announcement from the head of the mathematics department: “Statistically

speaking, humans are more likely to be alive than dead. You are more likely to live than to

die.” For how long? We don’t know. But at this moment there are more people inhabiting

the planet—eating cookies in bed, getting off at the wrong bus stop, picking fruit, misreading

text messages—than at any other time in history. Taking the mathematical view, death is

unlikely.

Other times there is no announcement in my office, and I walk in to see the math teacher is

lying on the floor. Uh oh, I think.

“I’m just stretching my bad back,” he says. “Walk around me, go on. And promise me

something.”

“Anything,” I say, hoping it’s easy.

“Don’t ever get old,” he says, rising. “It sucks.”

*

If you’ve got a few bucks, the 21st century allows for easier sleeping. There are

exterminators for vermin, there is internal heat and air conditioning, and a highly flammable

comforter can be purchased for around $20 at most department stores. And for those who are

difficult to love, there is even the hug-a-pillow, which recreates the human form in the shape

of a crescent moon for harmless spooning.

My boss at the UIC writing center, Vaynus, told me that in Lithuanian summers prior to the

industrial revolution, families slept under sheets soaked in cold water. More homes outside of

major urban areas were built half submerged in earth or dug into hillsides. And it wasn’t until

the 20th century that fleas and bedbugs were evicted from the bedroom; up until then, even

kings and queens had fleas.

*

In paintings, the incubus is seen either lying prostrate over a sleeper, or sitting hunched

on the sleeper’s chest—see Fuseli’s “Nightmare.” What’s this ghost monster’s agenda?

Reportedly, he robs the semen of men (detailed reports desired) and uses it to conceive with

a woman. St. Augustine, in his book City of God, had to throw up his hands in weariness at

the number of incubi assaults. There were so many reports “…which trustworthy persons

who have heard the experience of others corroborate… that it were impudent to deny [their

existence.]” Augustine’s predecessor, St. Thomas of Aquinas, would return to this topic and

explain, with the cold logic of a man convinced, that children born from these couplings were

mortal, but with increased powers, like exceptional beauty and immodest ambition.

Who were these power babies? To name a few: “Romulus and Remus, Plato, and

Alexander the Great.” Are you handsome? Are you ambitious? You might be the product of

supernatural union.

*

Faith is dying all around us. My friend Brett works construction, and when the boss is away,

half of the team drifts off task. Someone cracks open a Carlsberg beer and passes the bottle

around. Things appear: hunks of bread, a bottle of ketchup, salami rolls.

Then the boss’s car pulls in view of the window out front. Half-filled bottles are flung out of

second story windows, caulk guns spit madly, a powersaw sings to life and snaps scrapwood

in half, splinters fly; grown men hammer nails where no nails must go.

When I wake up in the morning it’s as though I’m catching my body off guard and its

laborers have tumbled into hopeless action. They want to stay employed. But all I can think

about is being hit by a car on the way to work, or the need to buy a security alarm for the rear

window. I grow deeply conservative in the early morning.

*

Not to be outdone by St. Augustine or St. Aquinas, Pope Sylvester II (999-1003) admitted

to repeated relations with a female incubus, though the encounters were prior to his papacy.

He revealed this on his deathbed, needing to get the affair off his chest and die repentant.

But this might not be reliable. Reports of his death vary wildly. One involves a devil stealing

Pope Sylvester’s eyes, another reports that the devil never left his side, padding along in the

form of a black dog.

A heavy conscience, de-occulization, stalwart dogs: all of these things make rest difficult.

*

Marco is a talented tattoo artist in Oak Park. Nine years ago I sat in his old Ashland studio

while my friend Erik got tattooed. Over the buzz of the needle and between gentle wipes with

the blood rag, Marco told us how his house was haunted. With sexy ghosts.

“I’m not kiddin’ you guys. It’s happened twice,” he said. “This ghost is screwing me in my

sleep. I wake up, you know, at the big moment,” he made a slow explosion gesture with his

hand, “and this warm figure is floating over me. And just what the hell am I supposed to do?”

We shrugged.

“And I got my kid in the other room. I mean, do I tell him about it?”

We shook our heads.

*

In defense of immortality, there is the appeal of nostalgia and the passing of things I might

miss. Like my body, which I use every day. Or cherry cola, which pours endlessly from

movie theater fountains. But can you be nostalgic for people, or does the mind accept death?

Can I have nostalgia for dead loved ones?

I am not nostalgic for my Grandma. I miss her, but I respect her death, too. Maybe a grave

is a picture frame. After the pain, her death helped me see her as a person completed and for

once understandable.

*

I’m scared of many things, like not doing my job well. Taxes frighten me, and so does

removing my wisdom teeth. I don’t want to get hit by a car again either, though I’m steeling

myself for it.

Louis Ferdinand Celine, ellipses master and author doctor, he got kicked out of France for

being an alleged Nazi collaborator. He wrote on dread and anxiety, too. “Never believe

straight off in a man’s unhappiness,” notes Celine. “Ask him if he can still sleep. If the

answer’s ‘yes,’ all’s well. That is enough.”

I almost fall asleep fine as an adult, but when I wake after about five hours of sleep, I think

about dying. With each day’s blooming moment, I’m shaking my head and imagining the bus

that will finally crush my bike asunder, or the mugging in a strange city that’ll leave me on a

bench, blood drained.

*

I’ve predicted a forecast for my travelling anxiety. My theory, which is uninformed, says that

in five more years there will be some sort of dread leaving my evenings and passing into the

afternoon, unfolding over me like overcast weather while I’m at work. Maybe it’s already

started.

Last week we were reading a Marquez short story about a dentist who works without

Novocain. A kid started asking about unreliable narrators when a stray sparrow slammed into

the classroom window. It hit it so hard the room thumped like a bass drum.

Chairs squeaked.

“Wow!” said one kid, slamming his palm on the desk.

“Oh, Mylanta! That’s so awful,” said another.

Everyone looked at me. I had nothing to give them.

*

All dreams are shitty metaphors. You’re lost at sea. You’re naked in front of the classroom.

Got it. But what about this: once I dreamed my friend Doug became a famous painter. He

took me to his studio for a dinner party. When I turned in a crowd to greet him I spilled my

wine glass on the prettiest woman in the room. I stared, humiliated. Doug tried to change the

subject and pointed to a mural on his wall. I found that I liked it. When I woke up, I drew the

mural from memory in my notebook. I saw Doug for lunch.

“Take it, it’s your artwork,” I said.

My dream made me the owner of that painting, but only as a British archeologist is the owner

of a grave-robbed Egyptian mummy. I wished Doug would have gotten more excited about

my discovery of his work—entered it in contests and turned it into a handbag for young art

students to buy from Blick on State Street.

Then I could go on TV or blogs and say, “Certainly it is his drawing, but did I not discover

it?”

Nothing happened. Doug made some details with a pen and slipped it into his wallet in a way

that didn’t put our friendship in jeopardy. I’m compelled to embellish this story should I tell

it again. Why do I remember this dream?

*

I like the Old Testament with its portentous evenings and sledgehammer justice, relighting

dying fires, falling-down-a-well deaths and swinging ass’s jaws. I understand violence. It’s

peace and kindness and patience that confound me.

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to have a modern day interpreter of dreams, like

Joseph Son of Jacob. Between my brother and fourteen years of Catholic school, I have an

obsession for the morbid and gothic, but no way of reading the details. There remains the

need for explanation.

The lack of dream readers and decoders must be why so many Irish and Mexican kids turn

toward The Misfits, Bauhaus, The Smiths, and Morrissey. So many lyrics about dying all the

time but never being dead, so many two minutes and fifty-nine second monster songs.

*

All of my black band t-shirts are gray from over-washing. I’m mellowing now, and I write

short songs under a minute thirty seconds like verse/chorus/bridge and wear white shirts and

red sneakers. My zines get shorter, too.

When I am the master of my form, I’ll just write fortunes for the cookies in Chinese

restaurants. The best one I’ve ever read says, “It’s time to sleep; I’m going to dream now.”

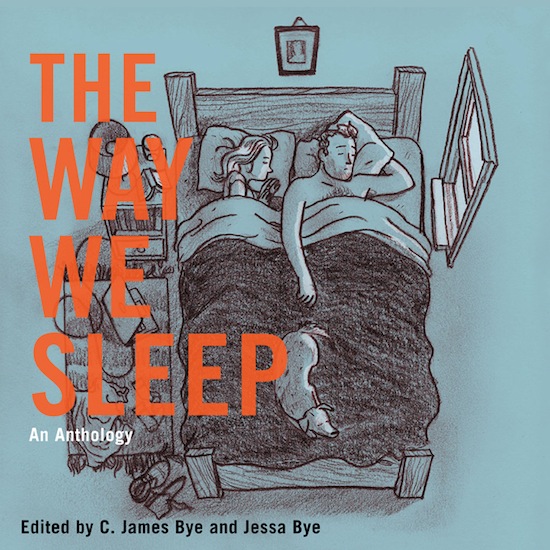

The Way We Sleep is available to order direct from the publisher, Curbside Splendor, at a discounted price

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more