‘A woman against the world has no resources but in herself. Her only means of action is to be what she is.’ Thus mused Joseph Conrad’s narrator in Chance (1914) on the predicament of his hapless protagonist, Flora de Barral. What goes for early 20th-century England is all the more pertinent for 17th-century Netherlands, the setting for Jessie Burton’s compelling debut novel, The Miniaturist – which, like Chance, tells of a young woman rudely imposed upon by calamity.

Petronella has moved to Amsterdam from the provincial town of Assendelft, aged eighteen, to be the wife of Johannes Brandt, a wealthy merchant. She is not marrying for love – the match represents, for this modest country girl, the best hope of comfort and material security – but she dares to hope that a fondness might arise in time. Nella struggles to find her feet in the unfamiliar cosmopolitan milieu, feeling less like an autonomous being and more like ‘a puppet, a vessel for others to pour in their speech.’ Johannes is worldly, wry and urbane, but disappointingly aloof; he is not unkind, but not terribly interested in her either.

Her tentative optimism is dashed: her husband has a terrible secret, one that threatens to endanger his business and his very life. A jealous former friend turned business rival, driven by a long-standing vendetta, instigates a conspiracy against him. With the spectre of catastrophe looming over her the couple, Nella is elevated from mere ‘puppet’ to would-be heroine, shedding her small-town innocence once and for all. In the process she draws solace and strength from the most unlikely, the most singularly bizarre of sources.

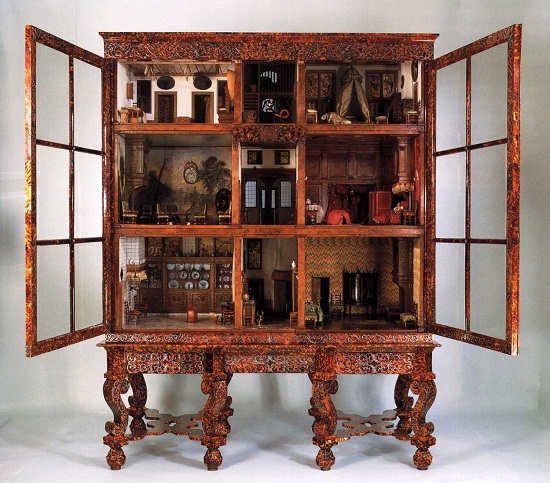

On the day of her arrival from Assendelft, Nella is presented with a curious wedding gift from her husband, a cabinet containing a magnificent doll’s house replica of her new marital home. In order to populate it, she engages the services of the novel’s eponymous artisan, a specialist in the manufacture of ‘small things.’ She sends off for a few pieces; they arrive, and are beautiful. And then the weirdness starts. The miniaturist begins sending her things she hasn’t asked for – tiny, perfect figurines that first echo and, later and more unsettlingly, appear to prefigure the various stages of the intrigue as it plays out. She asks the miniaturist to stop, but the little parcels keep turning up. Though duly spooked, in her despair Nella imagines the miniaturist as a sort of silent accomplice, a guardian angel watching over.

Nella and Johannes are ostensibly the novel’s co-protagonists, but it is in the mercurial figure of Marin, Johannes’ unmarried sister – and, prior to Nella’s arrival, the de facto head of the household – that the story has its true fulcrum. A paragon of puritanical austerity, Marin would have the household subsist on a diet of herrings for the good of their souls. Her asceticism pits her against the emergent craze for sweet things – an unfortunate aversion, given that the fate of Johannes’ business interests become increasingly bound up in a large stock of Surinamese sugar. When the local Burgomasters issue a ban on the baking and sale of gingerbread cakes in the forms of men and women, Marin approves, condemning simulacra as “Papistry … Idolatry. A heinous attempt to capture the human soul,” a sentiment later echoed by her servant, Cornelia, who remarks enigmatically that “Puppets are funny things.”

To credit a mysterious stranger with powers of clairvoyance, or to invest an effigy with quasi-divine cosmic energy – to look to either for guidance – is, in the pious parlance, to worship a false god. But who hasn’t, at some point, pinned their hopes on some lucky charm or other? It is a human impulse as deep as prayer. The Austrian novelist Rainer Mara Rilke has traced, in our obsession with dolls, an atavism of an earlier developmental stage:

‘Beginners in the world as we were …. We took our bearings from the doll. It was by nature lower, so we could flow off imperceptibly towards it, converge in it and, even if somewhat dimly, make out our new surroundings in it.’

The foggy canals of Amsterdam’s Golden Age may seem remote, but Burton’s crisp, elegant narration makes light work of the intervening centuries. The deft rendering of Marin, whose demonstrative abstemiousness masks a wellspring of contradictions, is The Miniaturist’s great triumph. If the Brandt household represents, in microcosm, the broadened horizons of a world made smaller by trade – decadent marzipan treats, a study adorned with rare animal skulls, a black manservant named Otto – then Marin’s personal confusion is likewise a cipher for the contradictions of her time, of a nascent liberalism colliding with entrenched Protestant mores. Cakes and dolls are merely a gateway drug; the true nemesis of the religious moralist isn’t desire but the Future to which it is a midwife, and it is telling that the novel’s final chapter, post-denouement, is entitled ‘Nova Hollandia.’

As the walls close in around Johannes, the embattled merchant bemoans “the years we all spend in invisible cages, whose bars are made of murderous hypocrisy.” He lashes out at his fellow citizens’ “bigoted piety – neighbours watching neighbours, twisting ropes to bind us all.” It is, then, a curious paradox of The Miniaturist that for all its anticlericalism it has a distinctly biblical feel about it. It is a parable of hypocrisy, its message one of generosity and of hope. The sign above the door to the miniaturist’s office declares ‘Everything man sees he takes for a toy.’ The line is wonderfully apposite: like the miniatures themselves, it is both utterly meaningless and profoundly powerful.

The Miniaturist is out now, published by Picador