The Hawthorn District, with its old factories, was situated a little outside the town, beneath the mountains in the east. I’d seen the buildings on my walks, and they would look back at me with their grimy square windows. In the daytime the area seemed uninhabited and frozen, silent as a photograph, but when I stepped off the tram I could hear music and see light and shadow move behind the windowpanes. Behind me the tram wheels screeched against the tracks, the wheels howling as it headed for the next stop. I turned off onto a road surrounded by red-brick houses. The road led to a huge old silo complex with eight cylindrical towers that reached up to the sky like a set of massive organ pipes. I noticed a little alley among the brick houses. That was where I was going.

The alley was unlit, and the old asphalt was full of cracks. Wet weeds were bent and then crushed beneath my shoes. I stopped in front of a big square warehouse with a flickering shimmer coming from a small window up by the roof. The rest of the wall was dark and smooth. When I knocked, the whole house was still black water beneath my hand.

The knocking seemed unnaturally loud. The echoes unrolled slowly, in and out of the sound of the tram tracks and of a car’s engine at a nearby multistorey car park. Then it was quiet. No footsteps or voices sounded from inside. I knocked once more, a little firmer. This time a light started flickering in the window under the roof, but still no sound. Maybe Carral Johnston thought it was too late for visitors, or perhaps she’d found a tenant already. I was about to start planning my route back to the hostel when the door opened.

The old warehouse interior had been renovated into an apartment with thin dividing walls made from plaster-board that didn’t quite reach halfway to the ceiling. The spaces behind them seemed more like booths than rooms. Carral Johnston gave me a tour of the plaster-board labyrinth. She was a slender girl, a few years older than me, wearing a tight pastel-yellow wool jumper that almost matched her pale yellow-white skin. Her yellow curls were tied up in a ponytail that rocked back and forth over her shoulders while she walked over the wooden floors with long silent steps. My boots thumped after her. Inside, too, I seemed to make unnaturally loud noises that buzzed on the tin ceiling above us.

We wound up by the kitchen table in the middle of the building, where the yellow Carral Johnston sat with her legs up on a chair. While she told me a little about herself – that she was from Brighton, that she had been here for three years, and that she worked as an office temp – I sat and watched her feet through the steam from my tea. Her toes curled up over a small fan heater, and her arched ankles made the movement look like a ballet exercise. In my boots my own feet were arching, as if they were trying to copy her movement.

‘So, Jo, what do you think?’ she asked smiling and continued without waiting for my reply: ‘We have a washing machine, TV, mattresses, everything we need. Plus a whole lot of weirdness. It’s an old warehouse after all. When I first moved in, I thought it was a little scary.’

I nodded and wondered whether I was part of this ‘we’, even though I had never been to her apartment before.

‘But it’s not scary, just different,’ she continued and leant towards me. ‘The house has a life of its own. You get used to it. Excuse me for a moment.’

Carral put her arched feet back on the floor, stood up and walked to the bathroom. When she left my sight, it was as if something took over the house, and it seemed to rock. The floor panels were rubbing against each other, the plasterboard swayed like long blades of grass. The thermostat clicked on and off, unable to decide whether the room was warm enough or not. The world outside rattled against the window. From the bathroom I could hear the sound of denim pulled over skin, the sound of skin coming to rest on porcelain, and finally a trickling, increasing and eventually steady stream of water.

‘Sound travels here.’

Her voice, bathed in echo, came from everywhere, as if she was speaking from the floorboards, the fan heater, the kitchen clock. The stream continued.

‘Luckily I’m pretty quiet.’

Only a small drip was to be heard now, a pause, and then finally crumpled tissue being dragged against skin.

‘Paper-thin walls,’ Carral said and giggled, but the sound of flushing drowned her laughter. ‘As I said, that’s just what this place is like.’ She opened the door again, returned to her chair and put her feet up on the heater. The tea had stopped steaming. She put her hands around the mug with a satisfied smile, as if she had accomplished something.

I hadn’t met a lot of girls who talked while they peed, and definitely not a lot of girls who talked about peeing while they did it. There’s usually a lull in the conversation even when you’re sat in neighbouring cubicles. Maybe peeing and talking is a bit like singing and playing an instrument at the same time, I thought, two sets of muscles having to work side by side.

‘Your English is great by the way,’ she said and smiled.

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘we all grow up with the BBC where I’m from.’

‘Well, I’ve met other Norwegians. They all had terrible American accents.’ She still smiled the same interested smile.

‘You’re probably right,’ I said.

‘Speaking of you . . . Why did you come to Aybourne?’

‘I’m studying biology. Bachelor of Science, I think it’s called.’

‘But here? Why would you study here?’

‘I wanted to come here,’ I answered. ‘It’s a good university.’

‘So you’ve left everything behind to live here for three years. I hope you don’t have a boyfriend waiting for you back in Norway.’

Carral giggled teasingly and put her arms behind her head. The thin jumper pulled over her belly and the fabric tightened over her breasts. I couldn’t see any trace of her nipples.

‘No boyfriend,’ I replied in the calmest tone I could muster.

‘Sounds good. You’re so young.’

Later that evening, after I had checked out of the hostel and said goodbye to the wank mirror and the golf clubs wrapped in black body bags behind the reception desk, I lay awake in my new bed and listened to Carral leaf through the pages of a book. I heard her fingers scrape the rough paper, the spine creak and the binding tighten. Later when I woke up my light was out but I could make out a glimmering halo of light over her bedroom wall, and in almost imperceptible noises at night I imagined hearing the hint of her curls falling over her cheek as she turned. Later the fridge started to hum. I was sure I heard tiny ripples on the surface of the milk inside its carton.

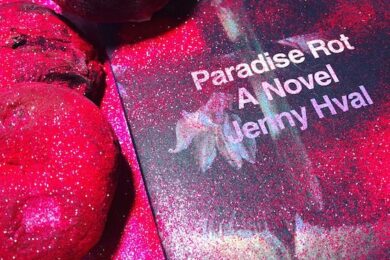

Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval is out now from Verso