Devourings marks the prose-writing debut of James Vella, until now, perhaps, better known for his endeavours in music – his band, yndi halda, his solo project A Lily, and his work with the near-legendary independent label FatCat. And, while it’s almost always best to judge a divergent output like this as a singular work – or, at least, a possible first of many – there are parallels to be drawn. Even though the Mediterranean roots of Vella’s short story collection, being himself part-Maltese, is a far-cry from those acts with which he is connected (the Icelandic bands múm and Sigur Rós, and his own Norse-named Yndi Halda) it is fair to say, consciously or otherwise, that their influence has left its mark on the pages – by turns, sparse, sprawling, eviscerating and uplifting – of Devourings.

As the foreword has it: "The shortest tale can leave the longest impression. Devourings collects a variety of stories which connect with absolute potency. Each piece is its own, but bound to the next by a broader, unifying theme: being enveloped, devoured, by a moment, an encounter, a political sit- uation, an emotion. Be they over a handful of paragraphs or a spread of pages, these short – and shorter – stories linger with a palpable resonance."

The Mediterranean blinked thousands of times over. Fleeting miniature brilliances caught the ripples on the water’s surface. The house of Sant Cassia overlooked the stony bay, watching the flickering sea and braving the young summer’s wild heat. The veranda overlooked stillness, a soft xlokk wind from the south warmed the air and pushed the bay waters up to the rocky coast. No animal movement caught the eye, no white wisp clouded the bright blue.

Valuto Sant Cassia spoke tenderly to his wife.

"Will you take some time off work to look after Valuto?" Isla Sant Cassia said. She spoke of their son, named with pride after his father.

Approaching his 80th year, Valuto assented sadly, wheezing in the heat.

"Of course I will, dear. I’ll call the factory and tell them."

"Tell them what, darling?" asked Isla.

Valuto kissed his wife’s spotted forehead, the per fect, browned tones of her skin broken here and there by sun freckles or blue veins. She smiled fondly up at her husband and held her hand out to his. Her hands were cherubic amidst rooster-claw wrinkles.

"I have some coins in my purse, if Valuto needs his pocket money," Isla said.

Valuto restrained his sadness as he thanked his wife. His walk from the shaded veranda into their son’s bedroom was slow and aged. His son lay motionless on a blue-blanketed bed, unshaven and unmoved for weeks, an expression of quiescent defeat at his eyes. Valuto ambled through his usual conversations with his son as he replaced the cold press against Valuto junior’s forehead and padded up his pillows. Valuto junior remained silent, still, held by the room, chattering his teeth for a vanishing second as his father laid the icy press to his damp forehead.

Three of us crossed the bay to the tiny island a few hundred metres out from the coast. I could see the island and its lime-sand statue of Saint Paul from the east side of the house, and the red stone manor looked back at me from the island. David – the oldest boy, bullish and barefooted – piloted his scruffy boat out of the bay, and we gingerly stepped from the loosely moored cockleshell float out onto the hot uninhabited rock. David and Giovanni teased my cautious dismount.

"I caught a lizard!" David shouted from the statue as Giovanni and I poked at shells with our fingertips, a short while into our visit.

"You didn’t!" Giovanni shouted back, excited. "No one can catch a lizard!"

We ran over to the statue and David’s cupped hands. A green tail poked between his fingers.

"What should we do with it?" David said.

We looked at each other.

"Make Valuto eat it!" Giovanni said. I cast a scornful glare towards him. I pushed him, called him a pastizz.

"No, Gio’s right," David said. "We can use the boat whenever we want, but you need to pay for your place, Valuto. Unless you want us to leave you here on the rock?" I felt Giovanni’s ugly grin behind me.

"Eat it!" he said between his teeth. David flashed the scaly green prize at me, its confusion frantic between his palms.

"I won’t eat it."

"All right, then we’re leaving you here," Giovanni said. He pulled David by the shirtless shoulder, back towards the boat. I looked up to the scorching afternoon sun, around the shelterless island, at the expanse between us and the shoreline.

"Okay," I heard myself say. David and Giovanni looked at each other victoriously, disbelieving their luck. "Give it to me." David held his cupped hands over my outstretched palms.

"If you let it escape I won’t let you back on the boat either."

The condemned creature flapped and flicked in my hands. I threw it between my teeth and wretched as its rough skin and desperate, miniature claws scratched the sides of my throat. I felt its body burst.

Valuto leant across his son’s still bed and turned off the radio at his side. He searched for his monogrammed pen in his pockets but felt just his old chest and his braces. He dropped his empty crossword down onto a brocaded armchair, adjacent to Valuto junior’s bedside, and began to recount his morning movements. He passed through the courtyard, retreading – as he always did – the paw prints of a long-passed family dog etched indelibly into the once-soft concrete surface. He was graced by a milder sunlight, the heat fragmented by the branches of a single carob tree, planted by his son more than thirty years ago. He met the postboy in the sunny, red-bricked kitchen.

Valuto reached into his pocket and gave the boy his tip, a few small coins. The boy returned a priceless silver Lira piece, marked with old Latin and scratched over centuries.

"Thank you, Nicolo," Valuto said.

"I’ve given Nicolo his tip already," Isla called from upstairs, waking from her rest.

Nicolo and Valuto looked at each other. The boy smiled sympathetically to the old man.

Several years had passed and only ripples of the lizard memory remained. The part of myself that I had left sacrificed on the island that day was all but forgotten. I took a hunting trip with a girl from across the bay, a thin pretence to spend more time with her. We had spent much of the summer coyly avoiding each other’s adolescent glimpses as our friends swam in the radiant blue sea. We caught nothing on the trip, we barely tried.

Ylenia’s curled, chocolate hair splashed down onto her shoulders, and she finally looked at me fully. We sat alone in the back of my father’s car and I fumbled our cheap rifles onto the seats in front of us. The car, the rocky clifftop, the girl nearly twenty were illuminated by bright island moonlight reflecting up from the surface of the sea. I held her sunned hips as she undressed, and she pulled me onto her, wanting to feel the weight of my chest on hers. We looked for and we found each other.

Later, we shared her thin sundress as a pillow, lying side by side on the back seat of the car, facing each other, immersed and disarmed. I ran my fingers across her girlish shoulders, ambrosial with her perfume and her sweat.

"You’re beautiful," I told her. She smiled and touched my nose with hers.

"We didn’t catch any rabbits, Valuto," she said. "What will we say?"

I pulled her close to me and held the back of her head to the crook of my shoulder with my palm.

Without warning, she was gone. I held only a shocking wisp of air between my arms. The jolt of sudden absence and my immediate solitude were frightening and cold.

A high dusk simmered at the bay, its air already boiled by an unyielding sun throughout the afternoon. Isla Sant Cassia sat opposite her son, contentedly tearing pages from a book. Her husband turned down Valuto junior’s radio to listen to her whisper a song to herself. Her son suddenly seemed sad and alone, and Isla wrestled through the fog around her to reach him. She leant across to him and touched his still shinbone.

"Can you hear me, Valuto?" Isla said. Valuto remained motionless, his expression unchanged. Isla turned to her husband. "Why can’t he hear me?" she asked him.

"He’s a little unwell," her husband replied.

Isla’s dark brow was puzzled, distressed. She tried to speak to her son again and felt a clarity form amidst the cloud. She felt a spark of abandonment, a spark of frustration, and the question she had for her son had slipped from her grasp. A dream interrupted, a knotted thread pulled straight.

Valuto touched Isla’s hand, still on their son’s shinbone, as he laboured from his chair and down the high-walled corridor out to the veranda, set up above the bay on the steep hillside. The soft palette spanning the sky broke the unremitting daytime blue, and Valuto thought to a similarly coloured evening, some decades ago. A younger man, he held his son, tiny and wordlessly inquisitive, in his arms and together they looked over the bay.

When I met Mia, she was confident and coquettish, plump and youthful. Her eyes wandered to mine often and seemed to open wider than Ylenia’s when I spoke. She wanted to hear me, and she told me that I listened well. Over weeks, I lost interest in anything else. I shaved every morning for Mia, I straightened my tie and collar for Mia, I tried to walk with my shoulders back as if she watched every step. I began to swim at dawn, firstly to banish her pretty ghost from my mind, eventually to sweat away the childish fat at my sides.

"Valuto . . .?" she sauntered through my name, teasing out every syllable. I was pleased every time she chose me to speak to. "You’ve picked up a tan," she told me, looking back over her shoulder as she walked away. I pretended not to be consumed by her.

That evening, Ylenia wanted to tell me about the rabbit she had prepared for us, but Mia’s voice remained, unshaken from my thoughts. Ylenia tried to bring me small happinesses, lovingly. I returned detachment only. Mia’s became the hot leg over my body and womanly shape at my side when we slept, Mia’s became the lips against my neck and quiet moans when we didn’t. It happened so quietly I barely noticed it.

"I’m so sorry," I said to Mia a few weeks later. "My wife—"

"Please, Valuto?" she interrupted. "This is the loneliest I’ve ever felt."

She put her toes to mine as we stood opposite each other in the doorway to her home. Her eyes were at the same height as my mouth and she stared at my lips to apologise. I moved her hair to kiss her forehead and believed that would be the last touch I would allow myself.

Isla held her husband’s monogrammed ink pen babyishly between her dry fingers. She wrote on a soft- backed notepad, its cover bent and sun-baked from years spent on the veranda balcony. She looked out over the bay from her shaded nest, and watched a young sparrow trying to scramble onto the balcony ridge, chopping its wings in fits. The sparrow tried to land a handful of times before diving back to the lemon trees out on the incline of the hill. Isla’s melancholy half-smile revealed a prick of sadness as the sparrow flighted from her balcony.

I’m tired today, wrote Isla.

She left a line and continued.

Today I am tired.

She began, instead, to write the words of a song she remembered from her youth, and she sang in harmony with her husband’s ink pen.

Valuto clasped her shoulders as he looked across the page. He smiled tiredly as he located, after days of searching, his missing ink pen in Isla’s grasp.

Isla drew a line, arrow-straight, down the centre of the page. On the left side of the paper she drew a portrait of her son, clumsy and fragile, but a clear portrayal. His expression was malaise and disquiet. The right side of the paper frightened her husband. She traced the outline of her son, as she had started the first portrait, but detailed his skin with black, reptilian scales, bloodying the note pad with ink. The expression was ecstatic, deranged frenzy and feral eyes.

Isla finished the page with a third drawing. Her son again. Now catatonic, eyes open but impassive and colourless. The third portrait was divided, centrally through her son’s face by the line through the page.

The sparrow returned to the balcony, finally finding foothold for its landing. Valuto watched his wife swallow sorrowfully as the sparrow sunned itself on the ledge, flickering towards the movements that caught its eye. The sparrow looked at Valuto and Isla and darted back to the lemon trees out on the incline of the hill below.

Ylenia was heartbreak and anger when she left.The house was silent and maddening. I had tried to argue, tried to refuse culpability, but realised, as my wife’s voice cracked through her tears, that my defence was a translucent veil for an awful guilt. We battled each other through the humid night, reaching no new ground and falling no further from miserable love with each other. By sunrise, Ylenia had left. The loving ghost of Mia became a haunting banshee, permanent and terrible. I tried to drink alone in the stairwell from which I watched my wife retreat, leaving the door open behind her, but I struggled to quiet the remaining words I wanted to say to her. I left the house, and I listened to them numbly as I walked into the dawn.

Blindly, I found myself at the bay where I spent my youth, looking up at the house in which I was born. I knew my mother would be awake, old and confused, barely remembering my wife’s name, long retired from the kitchen she used to purpose so well. I looked blankly over the bay to the island across the water. I noticed a black shape at the statue of Saint Paul, and I stepped, fully clothed, into the sea.

I began to swim, dragging my heavy body through the waves. The surface was still, but the undercurrents brawled with each other and with me. I sank one or two times and flailed back up to the air. The dawn light was not quite enough to make the sea clear like the daytime, and I realised that I had still half the distance to swim.

I lost myself repeatedly, unhappy and fixated on the widening black shape at the statue, often pulled under the ripples. My wet clothes and shoes hung heavily onto me.

I finally grasped the rough, porous rock of the tiny island, my eyes filled with salt and unseeing. I lifted myself onto a hot precipice, the same mooring we would rope our shabby boat to as boys, and the sinews in my shoulders cried. I stumbled to the statue and I saw nothing.

The Eater was standing behind the statue. It was me. A transient dichotomy. It was the part of me I lost in that traumatic trip to the island as a boy. It was the vicious and animal Valuto, forcibly sheared from me by circumstance and fear. The Eater waited for me to reach the lime-sand figure before he emerged from the shadow behind Saint Paul. He held an eel tight in his fist, thrashing wildly. The Eater tore a welt of flesh from the eel’s side with his teeth and chewed on it roughly.

"How long have you been here?" I asked The Eater.

"You already know," he said, approaching me. My skin goosefleshed with fear as he dropped the suffering eel into the dust. The Eater leapt for me.

A few hours later, I caught two or three words of the voices around me. I heard my father realise that the collapsed figure at the island was his son, and I felt my body lifted and taken onto a boat, out of the hot sun.

"Is that Valuto?" I heard my mother ask my father as I was carried to the bedroom I grew up in.

"What’s happened?"

"I don’t know, dear," my father said.

I tried to hear more, to reply, but I was hazed by a deafening bewilderment, unable to move and unable to speak.

One of our neighbour’s sons had married an English woman. I heard their children’s strange accent as they played in the courtyard between the houses, I heard them at the edge of the water catching the fish I ate so readily in my years on the island.

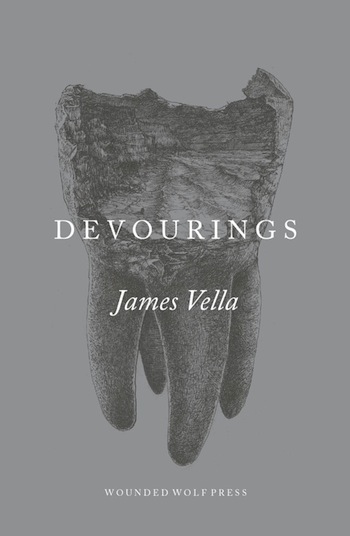

Devourings is published by Wounded Wolf Press, available to order directly from their website