Eventually we settle in the very far end of the hotel lobby; two men, divided by 50 years of life, talking as guests check in and out, as room service is delivered and dirty crockery carried back to the kitchens. It’s as good a place as any to meet James Salter, the 87-year-old author of A Sport and a Pastime, Light Years and All That Is: in his fiction, the hotel is a recurrent motif, a doorway to erotic possibility, a place of restlessness, and ultimately a symbol of impermanence. The grandness of this particular hotel, however, suggests one further thing: that James Salter, the most underrated of underrated American writers, has finally, belatedly, hit the big time.

At least two profiles have appeared in the last week proclaiming Salter to be the greatest writer you’ve either never heard of, or have never read. It’s a presumption that makes for nice copy, but that slyly avoids the less exciting truth. Salter has always had fans: ardent, vocal, a little smug for having discovered him. Usually other writers, readers deeply engaged with American fiction, those that have happened upon him in the Paris Review. But yes, certainly under-read; more so perhaps even than Richard Yates once was. Salter at least has the good fortune to be alive when the applause he so keenly deserves finally arrives.

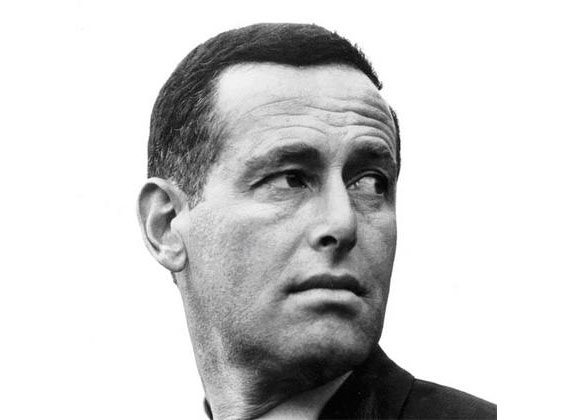

James Salter is dressed in a smart check shirt, chinos and a sports jacket. He is polite and has retained his rugged, rangy good looks, though there is no question that he looks his age. He answers questions with slow precision in a warm, low burr. He was an air-force man for a dozen years, flew fighter planes before writing two novels, The Hunters and The Arm of Flesh, that drew on his experiences in the air. But it is the following two novels – A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years – as well as his stories on which his reputation rests.

It is his sentences that readers come back to. Sentences that for many, including Richard Ford, are unmatched by any other living writer. Perfectly hewn, perfectly weighted, they can strike at the heart of a person, an emotion, a time of life and pin it like a butterfly. Taken out of context, they don’t have the same heft, but lines such as ‘The lines that penetrate us are slender, like the flukes that live in river water and enter the bodies of swimmers’ (Light Years). ‘One should not believe too strongly in a life which can easily vanish’ (A Sport and a Pastime) and ‘Billy was under the house. It was cool there, it smelled of the unturned earth of fifty years’ (‘Dirt’) give the merest hint of the shimmering yet spare style that is uniquely Salter’s.

I ask him whether this style has been developed in spite of being an American rather than because of it. His books are, unusually for an American writer, European in setting – and also seem to have more in common with European literature than the grand narratives of Roth, Delillo, Mailer or Bellow. “I’d hate to think I sound European” he replies, “as that would make me an alien in my own country.” For the first time I see something quite different in his eyes; a flash of perhaps the man of thirty-seven years ago who wrote Light Years and got a critical mauling for his troubles (in an event on the Southbank this week, Salter was asked if he held any grudges against any of those critics. “I did, but then he died,” he responded). But then it disappears. “There’s probably some truth in it,” he concedes.

Looking for antecedents and influences in Salter is pointless: he will only mention, when I ask who influenced his writing, that he began by imitating French writers – but will not name them. And while one might see the DNA of Thomas Wolfe, André Gide, Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald in his prose, the end result is all his own: writing based on experience, filtered through a sensibility wrought in the emotional and sexual freedom of escaping the duties of home.

“I have a lot of affection for Europe,” he says “probably because I’ve never had any responsibilities here. Any civil responsibilities any national allegiance here. I’m still at the end of a long love affair with Europe. There’s no sex in it anymore, but there’s the memory of all that.”

And it’s the memory of all that which is in part responsible for the late return to long form fiction. Thirty-four years have elapsed between the publication of Salter’s last novel, Solo Faces, and the emergence of All That Is. With such hiatus comes high expectation, expectation heightened by a plot that promises a sweeping, seductive love story beginning in World War II and taking in the big events of the second half of the 20th Century. Before the book was published, this description hinted at something epic, something kaleidoscopic and sprawling, a brick of a book to confirm Salter’s belated entry into that list of Great American Novelists. It is emphatically not that book. “I hope people won’t be disappointed,” he says dryly.

All That Is has not been slaved over for the last three decades – Salter says that for most of that time he was just “writing stories, wasting some time” – and the lyrical, shimmering prose that devotees underline and underscore in deference to his genius is less evident, more restrained for much of the novel. It is an altogether quieter affair. “The fact is,” he says when asks about the novel’s beginnings, “that certain things were ending, certain people and certain ways and I suppose I wanted to write something about it.” And that is its tone: elegiac, plaited with melancholia, a billet-doux sent to the cigarette-and-sex scented past.

The novel begins with a description of a sea battle, the opening line – ‘All night in darkness the water sped past’ – echoing the celebrated first sentence of Light Years (‘We dash the black river, its flats smooth as stone’). Unmistakably we are in a Salter story, yet in the subsequent ten pages the writing feels sluggish, deadened by research and a lack of full engagement with the physicality of battle. ‘It was a day Bowman would never forget. Neither would any of them.’ Salter writes, the cliché sticky as jam on the page.

It’s a puzzling beginning, a composition that Salter describes as “merely reconstructed history” and one that reads like it. The vitality, the originality, the vibrancy of Salter’s best writing seems to be worn out after that first sentence, potentially leaving established fans confused, and new readers puzzled at just what it is that everyone else sees in these mythical sentences of Salter’s. As we leave the war, however, the rhythms and writing seem to settle. His prose is more restrained than it has been before, more concise, but it is inescapably Salter. After the false notes of battle, we are soon on more familiar seas.

“You have to take this book for what it is and the way it expresses itself,” Salter says. “It’s taking some liberties with itself. And it’s hoping that the reader will get it and understand that.” This could be applied to every fiction Salter has ever published; but perhaps in All That Is Salter is sounding more of a note of warning. The narrative arc of All That Is is – on the face of it – more conventional than Light Years and A Sport and a Pastime. There are no time shifts, no dreamlike moves from one tense to another. What is promised is a straight story: the life of Philip Bowman from the war to the embers of the century. What Salter delivers is both precisely that, and nothing of the sort.

After the war, Bowman drifts into publishing, marries, divorces, embarks on passionate affairs. This is what counts for plot. He is “at ease in the visible world, familiar” and Salter gives us his life in episodic, digressive flashes: as though perhaps he had died on the war-ship and his life-to-come had flashed before his eyes. It’s an expectation that Bowman will figure on every page; that he will be of primary concern to both Salter and the reader. But this is not how the book works. “It’s not,” as Salter said when I asked about the temptation to write a big book, “how I write.”

Bowman is constructed not just by his own life, but by those around him: close friends, acquaintances, people he meets in restaurants and shops. These lives are given time and space, Salter penning micro-biographies that, at least on the surface, have no real significance to Bowman’s personal narrative. “Most readers I would say would expect them to continue on and show up in the story two chapters later,” Salter says. But these characters do not. They are like the people we meet in life; sometimes significant, sometimes fleeting, but always imprinted, however briefly, on our personal histories.

And All That Is is very much about personal over public histories. Salter takes an almost perverse pleasure in not giving away the exact timing of events. Kennedy is assassinated with the turning on of a radio, but otherwise we are given few pointers as to the exact timing of events. We only know, for example, that the book ends in the eighties because a wedding takes place in 1984 and there is mention of Brideshead Revisited on the television. It is a conscious effort by Salter to show the cleave between what history deems important, and what is important for those who live through it. And what remains important to Salter is the intense pleasures and pains of life: the visceral feelings provoked by sex, by art, by love and its loss.

These themes converge in a sublime piece of writing, possibly some of the finest of Salter’s long career, towards the end of the book. In a classic Salter scene – an adulterous excursion, a Parisian hotel, an older man and a younger woman – you feel the interior lives of both characters, exposed in all their faults and vanities. It is heart-breaking and exquisite, one of many jewelled fragments in amongst a mesmerising whole.

“With the novel,” Salter says, “you can express yourself fully. So long as you don’t get out of line.” It is precisely this discipline which makes All That Is an elliptical novel of rare resonance and power. It handles the vital questions of life – how can we live within each moment while also fully understanding it? How true are our recollections? And how will we be remembered after we are nothing but other people’s memories? – with deftness and understated intelligence. It will sit alongside the Collected Stories, A Sport and a Pastime and Light Years as his defining work. It is the reason why, finally, James Salter has hit the big time.

All That Is is available now, published by Picador