Sixty-six-year-old author James Ellroy, the self-proclaimed “Demon Dog” of American literature, casts an imposing physical presence within a small office at his London publishing house. Tall, fit, well built, sporting a smart-casual jeans and checked shirt look, with a grey moustache and a severely shaved head, the six-foot-four historical novelist/crime writer possesses a penetrating gaze, only exacerbated by his oval glasses.

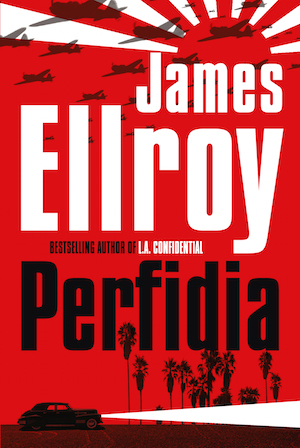

In the midst of the November 2014 UK leg of his long book tour to promote his ambitious and vibrant new novel, Perfidia, Ellroy is obviously weary but has graciously granted a brief, face to face interview at short notice before catching a train to yet another book launch event. Ellroy is a friendly and helpful interviewee (perhaps because I’ve interviewed him many times over the past 24 years), but he remains preoccupied and detached. The man is obviously a loner, who dwells within his own head for much of the time and who cannot wait to return to his craft.

Ellroy is both decorous and slightly ungainly. His fixed hangdog expression and lumbering gait seem at odds with his quick but considered southern Californian vocal delivery that mirrors his writing style. The myopic stare of James Ellroy, too, reveals much about his character – his suppressed anxiety, resolute obsession, locked down concentration, fierce determination and wild, black humour, are all be detectable there.

At this juncture, a rough, thumbnail sketch of Ellroy biography, outlined in full within his memoirs My Dark Places (1996) and The Hilliker Curse (2011), is required. Ellroy was born on 4th March 1948 in Los Angeles, a city with which he, through his fiction and biography, has become inextricably linked. His father ‘Big’ Lee Ellroy and his mother Geneva Hilliker met in 1939 and divorced by 1954. Lee was a Hollywood character, a former business manager for Rita Hayworth (who he claimed to have slept with). He chased women. The striking redheaded Geneva drank Early Times bourbon and was also promiscuous.

Ellroy would spend weekdays with his mother, three weekends a month with his father. Ellroy would sometimes find his mother in bed with strange men. Lee hid his liaisons from James. Ellroy loved Lee more. In 1956, his mother moved from West Hollywood to Santa Monica. Ellroy relished his weekends with the lazy Lee, who did not suffer moods swings from alcohol or send him to church on Sunday.

February 1958. Geneva Hilliker, a staff nurse at a Los Angeles factory, moved with James to El Monte. ‘Big’ Lee did not approve of the move to the San Gabriel Valley suburban town, 14 miles due east of downtown LA. Sent by Geneva to Anne Le Gore Elementary School, Ellroy’s grades began to improve. Shortly before June 1958, Geneva told James that he would have to choose if he wanted to live with her or his father. Ellroy replied that he wished to live with Lee. Geneva slapped him. James called her a drunk and a whore. She hit him again. Having cut his mouth on a table, he wished she were dead.

On the morning of June 22nd 1958, the corpse of 43-year-old Geneva Hilliker Ellroy was discovered in thick shrubbery, opposite Arryo High School football pitch in El Monte. Her assailant had raped Geneva, before he strangled her. The killer was never apprehended. When a policeman informed Ellroy on 22nd June that his mother had been killed his tears were “at best cosmetic, at worst an expression of relief.”

James Ellroy’s fascination with crime and the course of his whole life was set at the age of 10. His mother’s murder simultaneously shattered and gave shape to his existence. Nine months after the discovery of his mother’s body, Lee gave James a book by the actor of Dragnet TV show fame, Jack Webb. Entitled The Badge, it contained an account of the most notorious unsolved homicide in LA history: on 15th January 1947, the brutally mutilated corpse of a would-be starlet Elizabeth Short was discovered. Given the moniker ‘The Black Dahlia’, due to her lustrous black hair, Short had been tortured for days. She died chocking on her own blood, had been meticulously bisected at the waist and left on open ground at 39th and Norton. Within Ellroy’s frenetic imagination the two murders merged, The Black Dahlia’s grisly slaying assimilating the horror of his mother’s death.

His father finally died on 4th June 1965. This was the prelude to an aimless street level existence that would last for 12 years. These years would be dominated by petty crime (for which he would receive an aggregate total of four to eight months county jail time), pornography, masturbation and alcohol and drug abuse. He would also send many hours doing what he loved best; reading in public libraries.

By his late twenties, Ellroy’s consumption of cotton Benzedrex inhaler wads for amphetamine ruches had left him with a near-fatal lung abscess. Ellroy began to hear voices. At one juncture in the mid-1970s, after suffering an involuntary screaming fit, Ellroy was strapped to a hospital bed. He began scribbling on the wall: I will not go insane. Through herculean strength of will, by 1977, Ellroy was sober. Working as a golf caddie he began to pursue his cherished dream of becoming “the greatest crime writer that’s ever lived.”

At the very start of his writing career Ellroy rejected the Raymond Chandler-style private eye novel, having used it for his first semi-autobiographical work, Brown’s Requiem (1981), featuring the classical music-loving (a great passion of Ellroy’s life), former LA cop, Fritz Brown. Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 novel Red Harvest and the LA cop novels of Joseph Wambaugh where his greatest influences.

With his third novel Blood On The Moon, published in 1983 (filmed as Cop, starring James Woods, in 1987), Ellroy created his alternative to the clichéd sensitive, philosophising private eye with the highly intelligent and reactionary Detective Sergeant Lloyd Hopkins. Two Lloyd Hopkins novels followed – Because The Night (1985) and Suicide Hill (1986), but Ellroy was tired of the contemporary LA police procedural novel.

Ellroy had first approached the defining moment of his life in a tangential fashion. His second novel Clandestine (1982), his first cop saga set in 1950s LA, contained a fictionalised account of his mother’s murder and the introduction of one of his most sinister and dangerous creations, the magnificently corrupt Irish policeman Dudley Liam Smith. Then in 1987, the first instalment of his groundbreaking LA Quartet series of novels, an epic pop culture history of the City of Angels from 1947 to 1959, was published. Entitled The Black Dahlia, it carried the dedication: “Mother: Twenty-Nine Years Later, This Valediction In Blood.”

The Big Nowhere (1988), LA Confidential (1990) and White Jazz (1992) followed. Written as though in the throes of a fever, with prodigious amounts of sex, drugs, violence, mutilation, mayhem, inventive foul language, hipster slang and racial invective Ellroy’s obsessive, feuding cops were nearly as twisted as the killers they pursued. Fictional characters rubbed shoulders with real-life figures in high and lowlife settings. It was these international bestsellers that established Ellroy’s reputation.

During the mid-90s, encourage by his then second wife, novelist Helen Knode, Ellroy faced his mother’s death directly. A journalist friend had told Ellroy that he was going to be writing a story about unsolved murders in the San Gabriel Valley, during which he would be viewing his mother’s murder file. Unable to bear the knowledge that his friend would know facts about the case that he did not, Ellroy also requested to view the file. Bill Stoner, a homicide detective from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department showed Ellroy the material.

Stoner had served 32 years on the Sheriff’s Department. During his 15 years working homicide, Stoner solved the infamous Cotton Cub movie murder case and was on the Night Stalker serial killer task force. Stoner was then 53 and about to retire. Impressed by Stoner’s orderly intellect and compassion for female victims of male violence, Ellroy persuaded him to help re-open the investigation into Geneva Hilliker Ellroy’s murder.

Stoner and Ellroy’s findings were vividly outlined in the author’s first non-fiction book, My Dark Places – an LA Crime Memoir (1996). The crime remains unsolved to this day, but through the course of the 15-month investigation Ellroy grew closer to understanding and loving his mother. Ellroy had exploited his mother’s murder, as a great media story to help build his career as a crime writer. My Dark Places and the 2011 memoir The Hilliker Curse helped repay the debt, reclaiming her memory from her violent demise.

Ellroy’s fame and wealth only increased with Curtis Hanson’s Academy Award-winning adaptation of LA Confidential in 1997. “LA Confidential, the movie, is certainly the best thing that has ever happened to me that I had nothing to do with myself,” Ellroy told me in 2001. “It’s certainly not as harsh as the novel, but my characters were done justice, as was the book.”

With his following Underworld USA Trilogy – American Tabloid (1995), The Cold Six Thousand (2001) and Blood’s A Rover (2009) – Ellroy expanded his format, leaving genre fiction behind, to cover history on a national scale from 1958 until 1972. Once more, real-life public figures (such as Bobby Kennedy, Jimmy Hoffa, J Edgar Hoover, Martin Luther King) blended with fictional characters that actually shape mid-20th century US history in Ellroy’s savage, labyrinthine plotted but morally motivated fiction.

Having suffered a breakdown and separation from Helen Knode after 14 years of marriage in 2005 (described within the 2011 memoir, The Hilliker Curse), Ellroy returned to LA in 2006 from Kansas City, where the couple had lived. Here he wrote Perfidia, the first volume of The Second LA Quartet, which features fictional and real-life characters from the first two bodies of work in World War II, from the day before Pearl Harbour until V-J Day, as much younger people. When completed the three epic series of books will span 31 years of LA and American history, as one novelistic work.

Against the backdrop of the apparent suicide of a Japanese-American family, the wholesale internment of all Japanese-Americans and the war profiteering that will ensue after Pearl Harbour, events in Perfidia are viewed through the contrapuntal perspectives of four characters over a period of 23 days in December 1941, beginning on 6th December. These individuals are Hideo Ashida, a brilliant, closet homosexual Japanese-American police chemist, (mentioned in The Black Dahlia), Kay Lake (a lead character in The Black Dahlia) coerced into infiltrating a ring of Communist sympathisers within the Hollywood community (the aftermath of World War II is already being considered by the novel’s leading players), real life William H. Parker, a police captain who became head of the LAPD from 1950 until 1966 (who appeared in LA Confidential and White Jazz) and the evil Machiavellian Sgt. Dudley Smith (a major figure in The Big Nowhere, LA Confidential and White Jazz; Smith’s appearance in Clandestine is ignored as it is not in the Quartet and Ellroy now considers it a minor, early work).

The supporting cast of real life characters is as impressive as any in the Ellroy canon: movie stars Betty Davis (who is Dudley Smith’s lover) and Joan Crawford, Jack Webb, a former chief of Los Angeles police force James Edgar ‘Two Guns’ Davis, Elizabeth Short (revealed to be related to Dudley Smith), gangsters Benjamin ‘Bugsy’ Siegel and Mickey Cohen, playwright Bertolt Brecht and composer and pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, to name but a few.

The thrilling, razor sharp result is Ellroy’s “reckless verisimilitude”, which simultaneously obliterates the nostalgia now accorded the period yet celebrates the spirit of the World War II era, as his characters crawl their way towards some kind of redemption. As Ellroy used to say at book readings, Perfidia is a book for the whole family, if the name of your family is The Manson Family.

Enter James Ellroy.

Are you pleased with Perfidia?

James Ellroy: It’s a very openhearted book. It’s a very measured, finished, passionate book and it’s mature. If you have read and loved Blood’s A Rover you will see the derivation of it. It’s very much about belief. The geopolitical stakes are high, the language is rich and the characters are wild and strange and funny and loveable in weird ways, even Dudley Smith.

The action is heightened with the tight timeframe device you use, which you haven’t deployed before in your major novels.

Ellroy: No, I never have.

That time frame adds to the mania of it – and that it’s the beginning of World War II.

JE: Yeah, it was a bitch. We were under imminent threat of Japanese sea and air attack. There was the great injustice of the Japanese internment. There was a levelling of racial barriers and a heightening of racial barriers. As I said, the injustice of the interments, the fist fights, the increased sexual appetite, the chain-smoking, the booze, the dope, the partying, all of it. We did not know where this was going.

How did you come to hit on this idea of reintroducing your characters from previous novels and focussing on this particular period in LA history?

JE: I had the synaptic flash when I saw four forlorn, handcuffed Japanese-Americans in the back of a US Army transport vehicle hang up a snow covered pass to the Manzanar internment camp in the winter of ‘42. In a second, the notion, the idea of The Second LA Quartet had come to me. I knew the first novel would be called Perfidia, the song title, the haunting, beautiful love song of the time, the characters from the first two extended bodies of work, The First LA Quartet, the Underworld USA Trilogy, in Los Angeles during World War Two, would feature as significantly younger people and the first novel would be about the murder of a, perhaps subversive, Japanese-American family in the hours proceeding the Pearl Harbour attack.

Then it became a question of who are the protagonists? What is the scope and size of the book? I had my eyes set on a 700 page hardback and I got there, yeah. I knew that I needed a Japanese-American character, Hideo Ashida, who is mentioned very briefly in passing as one of the Japanese-Americans that Bucky Bleichert rats out to get on in the LAPD in The Black Dahlia. Kay Lake was actually easy; she’s my favourite female character, the one with the most dramatic potential. Then Dudley Smith. Yeah, you want Dudley. Yeah, you’ve got to have Dudley. You’ve got to show people the bad side there with Dudley. Then Dudley’s doppelganger – William H. Parker.

Wasn’t there a Japanese-American boyhood friend of yours who had some influence upon this saga?

JE: Just a kid I knew in study hall in ‘62 in High School (Fairfax), named Bob Takahashi. I barely knew him. He was a slick looking Japanese guy. He’s the one who hipped me to the internment. He went to Belmont High (near downtown LA). Jack Webb went to Belmont High. I think Mort Sahl (a comedian) went to Belmont High. Hideo Ashida and Bucky Bleichert (a lead character in The Black Dahlia and Perfidia) went to Belmont High. The Belmont High connection came to me. The geography came to me. Look at the back of that book [points to hardcover copy of Perfidia], the actual back board of the book. It’s got that haunting picture of the Arroyo Seco Parkway. That’s most of the locale of the book. Chinatown and Little Tokyo, you can see the pagodas there.

So, for Los Angeles, it’s quite a small area that most of the action takes place within Perfidia?

JE: Yeah, the house on Avenue 45 where the Watanabe family is killed is just north, out of frame of that photo.

With this new LA Quartet are you seeking to break down the romantic illusions that have developed over the years about the period you’re writing about? Not to denigrate the great heroic acts that were performed then, but like you did with your previous LA Quartet, peeling away the veil of sentimentality that has evolved?

JE: Yeah, but at the same time I celebrate that mentality. Like Kay Lake going down to enlist and the young man hoisting her up and she’s screaming, ‘America!’ Yeah, I wanted to celebrate that. I wanted to provide a social critique of its counterpart: the racial hysteria, the war profiteering, everybody getting rich off a geopolitical disaster of unprecedented measure.

This period of Japanese-American internment isn’t talked about in America and isn’t really known about over here, is it?

JE: Yeah. I thought there would be a lot of new attention given to the whole Japanese-American internment. I thought there’d be an ‘Ellroy writes about a great injustice’ aspect of this book and there has been very little. I tried to get a gig at the Japanese-American National Museum in Little Tokyo in LA. I think they saw this book and ran screaming.

With American Tabloid and the Underworld USA triology you turned your LA into the whole USA. Now, with this Second LA Quartet you seem to be turning your Los Angeles into the world; a world at war. Was that intentional?

JE: Yeah. I never set out to do that. In the writing of the text I saw that I was doing that. The grand design is to show what was then the emergent city in America. It’s really the city that World War II made. It built up and it built out and there were some men, early on, who saw the war itself as the ticket to the city’s expansion. Which morally is a ghastly thought and, by the same token… I see opportunity everywhere, that’s just me. It’s just opportunity, it’s an opportunity for all these guys. There are a lot of men in packs in this book, so it seems. The Mayor, the cops, are talking about this and that, in hilarious, hilarious terms. They’re going over to Kwan’s Chinese Pagoda, the opium den… come on, come on! We all wish we could be back at Kwan’s Chinese Pagoda with Salvador Dali’s leopard eating spare ribs off Count Basie’s plate. We all wish we could go to the party at The Trocadero, with Dudley Smith who is fucking Bettie Davis and Ben Siegel has just gotten out of jail, they’ve thrown the witness out the window and he’s paired off Brenda Allen’s chippies with the marines who are shipping out to the Pacific. Everybody is fucking and sucking and drinking and smoking opium and scared shitless

The gloves are off…

JE: Yeah, the gloves are off. I mean, come on, Kay Lake is your woman. She’s my woman. I want to go to those parties at Claire De Haven’s house and Rachmaninoff stumbles in and plays the piano.

Ah, that reminds me… [I hand Ellroy a leaflet outlining the current Rachmaninoff: Inside Out season at the South Bank]

JE: This is great, thank you. Holy shit. [He continues to read the leaflet] Ian ask me some questions.

Stylistically, Perfidia is different from the Underworld USA novels. Is that to evoke an earlier time?

JE: Sorry, I was distracted by Rachmaninoff there. Yeah, it was. It is also… These are four, even in my cannon, uniquely brilliant people – Ashida, Parker, Lake and Smith. Brilliant, brilliant people, they think a lot. They ponder meaning a lot. I had to explain the interior monologue.

Parker; is he the male hero of the novel?

JE: Yeah, yeah. He did very good supportive roles, dominated roles, he’s right at the heart of this series of novels. As is Dudley Smith, Kay Lake and Claire De Haven.

Some historians view World War II as a race war, driven by racial prejudice, racial pride and hate. Do you agree?

JE: Not on the side of the United States and Great Britain. I don’t know where they are coming up with that one.

In terms of the Japanese, the Germans…

JE: Oh yeah, we understand that. The Soviet Union as well. That was a completely anti-Semitic culture. The Japanese hated the Chinese and the Chinese hated the Japanese.

Obviously, the Right embraced eugenic science but in Perfidia you show the Left also took to this pseudo ‘science’…

JE: Jack London was a big racial science guy. He was on the blacklist, a socialist, a big racist.

That train of thought all coming from the 19th Century…

JE: Yeah, yeah.

Perfidia is a very funny novel. Lots of very black humour where Dudley Smith is concerned.

JE: Yeah, you’re in Dudley’s viewpoint and you have access to all his thoughts. He is just inherently evil and delightful. And Dr. Ruth Mildred Cressmeyer (abortionist to the stars): ‘I scraped her, she had a big bush.’ All that shit. It’s just deadly and delightful.

That scene where Dudley Smith is talking to Buzz Meeks but in his interior monologue he states that he’s going to kill him in 1946 is great…

JE: Yeah, Buzz Meeks fucking with Dudley Smith. I mean, Buzz Meeks is fearless but, as we know, in the prologue of LA Confidential, Dudley kills him.

Someone who has never read a word of your fiction would really enjoy this book. But obviously for longstanding devotees it’s a riot, because we are reunited with these characters. Were there certain characters you just couldn’t let go?

JE: Kay and Dudley. She’s deadly. She’s everything she thinks she might be and so she is, and more. She tries to kill Dudley. Nobody else has the courage to do what she does. And it’s 1941 and she’s a woman.

And she’s trying to take Parker on and stop what he’s trying to do. You are very sympathetic to her and her aims. In fact, a man of the left could have written the book, whereas you come from a very different perspective.

JE: Parker was right. Churchill was right. We should have gone after the Reds. Patton and Churchill, they wanted to go on into Russia (after World War II). No Cold War. A rebuilt, unified, democratic Europe. Not to be.

Things would be different now too…

JE: Yeah, they’ll have to be dealt with. There are some people who have to go, Ian.

So the next Second LA Quartet novel will pick up…

JE: Immediately. The summer of ‘42.

LA is now where you live again?

JE: Yeah. I’ve been back since 2006, eight years.

You like being back there?

JE: Yeah.

What car do you drive?

JE: I just ordered a Porsche 911 Carrera 4S convertible.

Nice. Is that your main luxury item?

JE: I’ve got a nice house. I’ve got some nice cashmere sweaters. I’ve ordered a nice car but it hasn’t arrived yet. I live in Bronson Canyon, the eastern most Cannon before Griffith Park — that sort of describes it.

Obviously this is all a work of imagination, but a lot of the time you’ve been writing about LA from afar.

JE: Yeah, yeah.

So was it different writing Perfidia with Los Angeles just out of the window?

JE: No, no, it’s just about consciousness. It’s just about trying, with all means available to you, to get it down.

Was there any specific text that was useful to you? Did you hire a researcher, as you’ve used on previous historical novels?

JE: I hired my usual researcher. She compiled fact sheets and chronologies. I was gratified to see that the first month of the interment, the round ups of the allegedly subversive Japanese were haphazardly implemented, so I had greater latitude to fictionalise.

Is your proposed Scotland Yard novel back on?

JE: No, I’m writing a motion picture remake of Laura [the classic 1944 film noir, directed by Otto Preminger, starring Gene Tierney] for 20th Century Fox. You’ve seen Laura? I’m setting it in London, Scotland Yard.

Wow.

JE: Yeah, I have the deal and I have to start work on it soon. I’ve got some other film and TV work in front of me.

I know you don’t have a television and only occasionally go to a friend’s house to watch shows or films but Perfidia would make a superb HBO-style television series. The format would be perfect for your epic style of fiction. Has there been any interest?

JE: Yeah, there are people who say they are interested, so where’s the money? When somebody coughs up some money that will be that. It would be a wonderful 12-hour wingding, but, you know, I never count on that. I never think about it. If someone comes around and pays me they can have the rights.

Any news from Bill Stoner?

JE: I haven’t talked to Bill in a while. No news on the case.

Do you still dine at the Pacific Dining Car? [A famous, swanky, downtown LA steak restaurant, originally a railway train car parked in a rented lot in 1921: Ellroy married Helen Knode here and they held their divorce party in the same location]

JE: Every chance I get.

Excellent. You can feel history seep out of the walls in there.

JE: Yeah, creeping up on you.

Any more collected works of journalism coming from you?

JE: Novels from here on in. No more memoirs, no more journalism.

Did you used to enjoy writing for magazines, as they used to be? There doesn’t seem to be much content these days…

JE: I enjoyed it while I wrote for them, GQ in the States. But I don’t put any time into moaning. I don’t use computers. I don’t have a cell phone. I’ve written all my books by hand. That’s just the way it is.

That’s going to be quite an archive.

JE: There is a University Archive, it’s at the University of South Carolina. All my notes, yeah, it’s a lot of paper.

With thanks to Sophie Mitchell

Perfidia is out now, published by William Heinemann