As a young punk, 1984 stood out to me as a literary disappointment.

I grew up in the heyday of Anonymous swarms, when Anti-Flag sang above the thinnest guitar of all: “Hell yeah I’m confused for sure what I thought was the New Millennium is 1984”. I was bound to pick it up. There was really no way around it. It just didn’t click with me. Blame it on the hormones, but Winston Smith’s love story and his heart-wrenching betrayal felt bland compared to the epic throes of high-school drama. Big Brother was neither big nor menacing. That boot wasn’t stomping on my face nearly as hard as I wished it would. I don’t mean to speak ill of the classics: Animal Farm did the trick way better, somehow blending in with the martial law paranoias and Antichrists in disguise that were seeping into the popular consciousness at that time. But I wanted more.

In hindsight, I think that my main problem was that I was looking for something that, luckily, George Orwell couldn’t provide: after hours spent slipping and sliding from one conspiracy theory to the next, I yearned for the taste of evil. Conspiracy theorists sighed: “How could Hell be any worse?”, and then took it as a challenge. By the 2010s it was all dystopia for dystopia’s sake. I couldn’t care less for a cautionary tale on the very real dangers of power. My eyes were coated in stories that were hallucinating the most disgusting oppression in the most banal MTV commercial. I was not looking for something to believe in or be warned by, I wanted it to drip extermination.

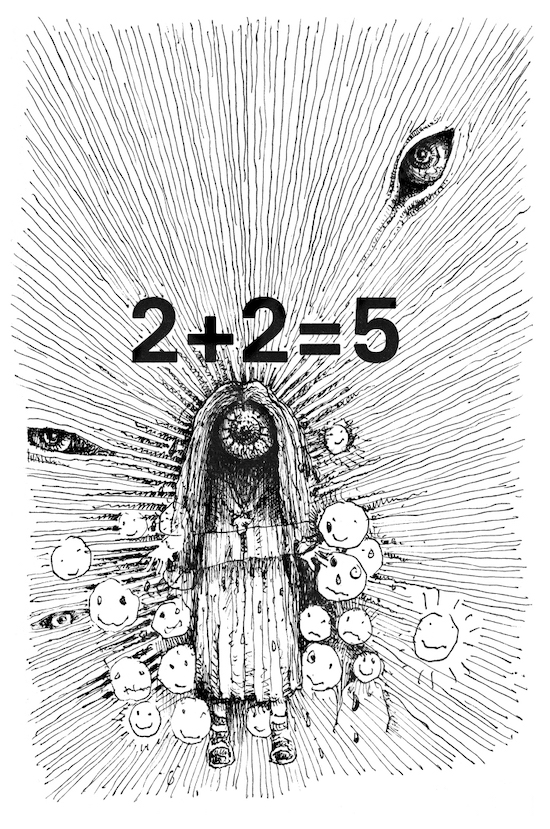

I should’ve been careful what I wished for. Extremist extraordinaire Jake Chapman gave the world what the little teenage creep I used to be was looking for. 2 + 2 = 5, his latest book, is, as its publisher Urbanomic puts it, a rectification of George Orwell’s 1984. It is certainly true that, on a very fundamental level, the book is just that. Chapman uses Orwell as palimpsest to re-imagine one of the most crucial works in contemporary literary fiction and, more generally, the popular imagination. But the term rectification implies a will to make something up-to-date and, in some sense, a little better. It hints at a latent meliorism.

2 + 2 = 5 really is anything but “better”. It is an assault and a denudement, both at George Orwell and our expenses. In a sense, Chapman rectifies 1984 just like Winston Smith rectified the news. Those who are familiar with Chapman’s work, both on his own and with his brother Dinos, won’t be surprised by this, but 2 + 2 = 5 is really just an excuse to use the dark glitz and glamour of dystopia’s shock-and-awe tactics to expose our wildest hunger and lusts and what Orwell couldn’t or wouldn’t say. At the end of the day, it is really an “appalling parasitical affront to the memory of George Orwell,” as Chapman himself put it recently, and that’s not half as bad as it sounds.

The basic tenet of 2 + 2 = 5 is quite simple. The long shadows of the Soviet Union and the totalitarian regimes have dissipated. The Doublethink and the psycho-police in their original, austere form have happily gone into retirement and something far more terrifying has taken their place: a state of compulsive mindfulness, productivity, and well-being. The all-seeing eye of the state now mandates Two Minutes of Compassion and it is deeply concerned with your sexual satisfaction and your breathing exercises.

Clearly, the social critique at the heart of this revision is plain to see: just like George Orwell was a victim of his tragic times so is Chapman puppeteered by his farcical epoch. An epoch in which the compulsion to produce, fuck, and enjoy are the crucial features not only of a life worth living, but of a healthy and flourishing economic global system. While Orwell had to confront the horrors of total states, Chapman denounces the monstrosity of psychedelic capitalism, an all-encompassing political system that won’t let you refuse your freedom to enjoy.

At this point, I think a warning is warranted: even for those who agree with this general sentiment and even without spoiling much of the debauchery (but take my word for it, it gets really dark), Chapman’s dystopia is exceptionally mean, even cruel at times. His depiction of contemporary societal ills goes toe to toe with the hallucinatory evil of writers like Curzio Malaparte and it never lets you go. Chapman’s Winston Smith strolls beneath towering vagina-shaped buildings and derides every possible responsibility and good sentiment. No light shines through these pages. Read something else if you are fond of constructive criticisms.

Even more worrying is the fact that, at a close inspection, it is quite apparent that critique is just the tip of the iceberg. An excuse to exercise the worst, really. 2 + 2 = 5 quickly derails from the straight and narrow path of social critique, to crash-land on far more disquieting grounds.

In fact, after ten pages or so it becomes quite evident that Chapman’s main goal is to expose our yearning for the terrible, and to make Orwell speak the pleasure of utter disgust. It soon becomes an exercise in excising the edifying veneer of the dystopic genre. The Big Book of Me, for example, the real villain of Chapman’s 1984 2.0, is really a bundle of neurotic impulses. A blank page on which we sputter and decode black lines just to see how much we enjoy reading that which is horrid. With our backs against the wall, Chapman forces to confront our inner passions for terror. We crave more boot in our 1984s, more hunger and blood in our Hunger (or Squid) Games.

Chapman’s main thesis boils down to: we read and write dystopias not to avert them, but to see how low they could go. And he really gives us more and more. I might find his book frightening, but deep down I know I could never look away.