On 1 July 1997, the philosopher Jacques Derrida walked on stage at the Paris La Villette jazz festival at the invitation of jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman, who he had spent the last week interviewing. Grabbing the microphone as Coleman played, Derrida began to speak, “What’s happening? What’s happening? What’s going to happen, Ornette, right now? Well, I need to improvise, I need to improvise, but well that is already a music lesson, your lesson, Ornette, that disturbs our old idea of improvisation – I even think you’ve sometimes deemed it racist, this ancient naïve idea of improvisation…”

Derrida wrote very little about music – references of any type in his vast corpus are rare. While he once claimed that this was because “music is the object of my strongest desire, and yet at the same time it remains completely forbidden. I don’t have the competence” little in his personal life suggest an affinity, apart from a touching devotion to listening to the Algerian music of his youth on his weekly car journey from the suburbs in to teach in Paris.

His interview of Ornette Coleman was his only major intervention. The pair had bonded over their mutual resistance to the cult of ‘improvisation’ – be it in writing or music. For both, true improvisation was an impossibility – all creation existed within a structure and had rules, meaning all originality was in some sense repetition, or, to use Derrida’s term, iteration.

There is, noted Derrida, “repetition, in the work, that is intrinsic to the initial creation… when people want to trap you between improvisation and the pre-written, they are wrong.” Or in Coleman’s words “Repetition is as natural as the fact that the earth rotates.”

The racism to which Derrida alluded was the idea that somehow jazz, in being ‘improvised’ was somehow closer to authenticity and therefore primitivism. The jazz player was in some sense animalistic, producing new sounds from their sheer corporeality, and that the musicians were overwhelmingly black (at least in the early days of jazz) this could shade easily into racism.

What is raised here is the question of ‘authenticity’, and it is central to Derrida’s thinking that true authenticity is a construction – a hope and a dream. As religion needs ‘God’ to make it work, philosophy needs ‘Truth’, and law needs ‘Justice’, art stakes a claim to ‘authenticity’. What is fascinating about popular music in particular is how playfully it has dealt with this idea, for better or worse.

“I’m in love with a Jacques Derrida/Read a page and know what I need to/Take apart my baby’s heart/I’m in love.”

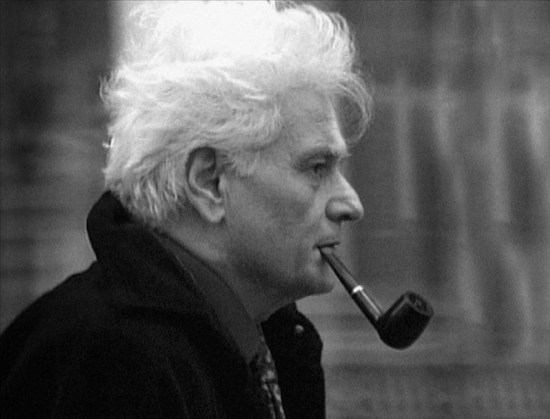

It is difficult to overestimate exactly how famous Derrida was in the 1980 and 90s. When Scritti Politti’s Green Gartside penned the song ‘Jacques Derrida’ in 1981, he was referencing a major figure in popular culture. Charismatic and handsome, with a shock of white hair and smoking a pipe, Derrida was everyone’s idea of what a French philosopher should be, while his gnomic utterances – “there is nothing outside the text”, “I always dream of a pen that would be a syringe”, “Cinema plus Psychoanalysis equals the Science of Ghosts” – were perfect for incorporation into pop culture without the necessity of reading him.

In popular music, it was both the start of the video age, and the start of a radical questioning of ideas of authenticity. Derrida’s insistence on beginning television interviews by pointing out the artificiality of the construct, and thus the limitations imposed on his answers, was exhilarating for a generation for whom the counterfeit nature of the televisual was becoming obvious, even as it took over the entire social space.

Derrida had questioned, amongst other things, the idea of presence, of immediate (and therefore unmediated) access to ‘truth’, to ‘reality’. In music, the idea of presence privileged, in the words of Kodwo Eshun, “the live show, the proper album, the Real Song, the Real Voice”. As Derrida had noted, we tend to regard the ‘voice in our head’ as somehow the authentic self, which, when converted to speech, communicates complete meaning to a completely receptive listener. Thus the cult of the singer-songwriter, acoustic guitar if possible, singing the truth, as though no artifice were involved.

But, as Gartside, amongst others pointed out, artifice is involved in every step. In a 1988 interview he says, ‘The mysticism of real players and heartfelt music – I think that’s all nonsense’. Sincerity is a pose like any other. But to recognise artificiality is not necessarily to dismiss it in popular music, Gartside himself moved Scritti Politti into that ‘sugary and teleological’ medium of ‘consolation.’

Pop was indeed eating itself. “If you’ve gone eight bars and there hasn’t been an inanity,” argued Gartside, “it’s time for a ‘baby’ or an ‘ooh’ or a ‘love’ or something.” Perhaps the Pixies 1989 song ‘La la Love You’ takes this to its logical conclusion, abjuring all lyrics except repeated declarations of love, the ‘maybes’ and the ‘babys’. It is music at its most self-referential.

At the same time, the unspoken congruence of music and capitalism was being spoken, sung about, and often celebrated. If Adorno had argued that popular songs were basically advertisements for themselves, then the wholly constructed band Sigue Sigue Sputnik would go a step further and actually include advertisements – some real, some fake – between tracks on their debut album Flaunt It, while hip hop began to embrace a model where songs were built around shameless self-promotion and declarations of wealth.

Later artists such as DJ Shadow with his Entroducing, and DJ Spooky on albums such as Riddim Warfare and J Dilla on Donuts were, in their own words, ‘deconstructing’ music – mixing genres, breaking songs off mid-sentence, incorporating samples and found sounds – in ways that have become familiar, but sound no less fresh. Witness an artist like Fire-Toolz, flipping between genres and modalities, often mid-bar.

And yet this problem of authenticity remains with us, as Mark Fisher points out in his ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle’. Fisher analyses that sonic accomplice to all popular music of the gramophone era, from early blues on, the crackle and hiss of the needle on the record. At once a signifier of authenticity – the singer was really there – and inauthenticity – being recorded artificially and having their voice taken and distributed – it became, with the advent of the CD and later technologies, a sort of inauthentic authenticity, as at the start of Beck’s ‘Where It’s At’ – its own appropriation of hip hop from perhaps the slickest of all genre tourists.

If, as Derrida argued, ‘the metaphysics of presence rests on the privileging of speech and the here-and-now, then the metaphysics of crackle is about dyschronia and disembodiment’ notes Fisher. Derrida in the late twentieth century had foregrounded presence and its artificiality, in the twenty-first century it was absence and its reality which became key in thinking about deconstruction and music.

Fisher adopted the term ‘hauntology’ from Derrida’s 1993 text Specters of Marx, which explored amongst other things, the productive nostalgia for lost futures. The music of such performers as Burial, The Caretaker and Ariel Pink, Fisher noted, “blurs contemporaneity with elements from the past, but, whereas postmodernism glosses over the temporal disjunctures, the hauntological artists foreground them.”

It is unlikely that the idea of founding a musical genre would have ever occurred to Jacques Derrida, particularly not that night in July 1997. As he continued to speak the crowd grew restive. Some booed, some left. Mortified, Derrida left the stage to catcalls. It was, he would later say “a very painful experience.” But, he added, “it was in the paper the next day, so it was a happy ending!”

An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida by Peter Salmon is published by Verso