David Keenan surveys his latest works soon after the publication of Monument Maker. Photo by Heather Leigh

This piece includes an ever so slight light spoiler warning for the end of the paragraph on Roberto Bolaño’s 2666.

That people still read and write long novels in this era of instant pleasures is a curious but gratifying fact. So much of modern culture is designed to deliver an instant hit, with a minimal expense of mental attention, that investment in a collection of words that may take weeks or even months to read and digest goes directly against the zeitgeist. With the ascendency of social media and flash fiction, it has even been suggested that the novel as a whole (let alone in its longer incarnation) is fast becoming a redundant artistic form. According to some statistics, however, novels are in fact becoming longer, and despite the potential for accusations of pretention, the ‘credibility bookshelf’ is available, fully-formed and ready for download as a background for video calls.

Yet despite the many demands upon our attention and the suspicions of motives sometimes cast by others, some of us just love to read long books. There is much to be said for the colossal compulsive page turner, as well as the literary monolith. The ability to hold a reader’s attention so well as to compel the turning of pages beyond the usual limits of tiredness or constraints of time is a rare and valuable trait. After all, reading is about immersion in other worlds and the empathic insights that seeing through the eyes of another character can bring. Perhaps above all else, fiction should have the potential to bring enjoyment as well as enlightenment, whatever the length of the text, and it is in an open and celebratory spirit that this article is intended.

The longest ever novel is supposedly Venmurasu, a modern reworking of the Sanskrit epic Mahabharatha by B. Jeyamohan, which clocks in at an astonishing 3,680,000 words or 4722 pages. The world’s longest novel according to the Guinness World Records, Marcel Proust’s In Search Of Lost Time, is a ‘mere’ 1,267,069 words by comparison. Joseph McElroy’s 1987 novel Women And Men, one of the longest novels ever written in North America, is an ‘even less impressive’ 850,000 words. Alan Moore’s incredible work of "genetic mythology" and psychedelic cosmology, Jerusalem, by comparison is an ‘easily digestible’ 600,000 words, or 1,266 pages, and Joyce’s Ulysses barely gets a look in at a ‘paltry’ 265,000 words, or 730 pages. Clearly size is relative and any discussions that attribute value on length alone are pointless.

A 2015 survey by the publisher Flipsnack looked at 2,515 books that had appeared on the New York Times bestseller and notable books lists and also considered an annual survey of Google’s most discussed books. The survey found that books have been increasing in length, at a fairly steady pace, for a couple of decades. Between 1999 and 2014 the average book length increased from 320 pages to 407 pages.

In 2019 the average length of the six books on the Booker Prize shortlist was at 530 pages. For the purposes of this piece, then, let’s consider books of around 500-600 pages as ‘longer’ works, even though they are by far not the longest.

Of course, one’s taste in fiction is relatively subjective. Even so, anyone with a abiding interest in literature, will likely be open to discovering what can be done with the form, with varying perspectives, points of view and textual lengths. Certainly there are novels that don’t really justify their own length, or that don’t reach outside of the novelist’s own ego enough to justify investing such a significant amount of attention in them. Yet equally, there are things that longer novels can accomplish that shorter ones cannot. If we consider film, even a long movie of 3 hours is limited in scope in comparison to a TV series of 12 one-hour episodes. There is a greater investment of time required, but also the potential to tell a more detailed story, with greater character development. The same obviously applies to the ‘longer’ novel.

There is also the question of difficulty. Many long literary novels do represent a steep learning curve. Many also repay the investment of attention, once a certain point has been reached. Joyce’s Ulysses is often cited as a difficult work, but it is far from impenetrable, unlike its sequel Finnegan’s Wake, which Mission Of Burma guitarist, Roger Miller, once told me took him 30 years to read. That book, written in a combination of as many as 60 different languages, represents another order of difficulty entirely. For Ulysses, or Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, one of the initial barriers to reading is the notion that the reader has to ‘get’ their many allusions the first time round. For Ulysses, a work of high literary modernism, those allusions are largely to the kind of classical mythology and early Christian philosophy no longer so uniformly taught in schools. It is entirely possible to read Ulysses without catching all of those references. There is a certain amount of ‘fun’ to be gained in reading about them too, of course, but perhaps not at the expense of enjoying the narrative. Frequent Quietus contributor, Jennifer Lucy Allan, recently remarked on Twitter that she had felt a real sense of accomplishment in finishing Ulysses. I asked her if she could convey her experience of reading the book. She replied:

"I found the experience of Ulysses to be more like a place I went to – not one I always liked to be honest, but one that I missed when it was gone. It made me understand why people go back to tomes like that. They’re like pubs – they stay the same, but are different each time you walk through the door. Ulysses especially is a bit like a pub, what with it being so much about pubs."

Literary writers who exhibit none of the skill of the page-turning bestseller risk putting their readers through a lot of hard work without offering a payoff in return. Alan Moore’s Jerusalem, for example, isn’t always an easy read, and I’ll confess that I largely skipped the section written in the style of Finnegan’s Wake. Much of the book, however, is totally addictive, compelling storytelling. ‘Book Two: Mansoul’, which largely concerns the exploits of ‘The Dead Dead Gang’, in a style that Moore himself described as “a savage, hallucinating Enid Blyton”, is an incredible piece of work, whose beguiling cosmology offers a system of ‘explaining reality’ on its many levels that has real weight, way beyond its purported function as fiction. This being Alan Moore – a writer (and magician) who once said “Life isn’t divided into genres. It’s a horrifying, romantic, tragic, comical, science-fiction cowboy detective novel. You know, with a bit of pornography if you’re lucky” –Jersualem isn’t simply a work of fantasy. Alistair Fruish, one of the book’s four editors, kindly provided this insight:

“One of the astonishing things about a work that took so long to complete that largely focused on a square mile in Northampton’s Boroughs, was that the discovery that industrial capitalism basically started in that square mile, with the creation of the first powered mill. Which comes to be central to the book itself, filled as it is with Blakean references, it kind of caps them off. I only made this discovery in the last few weeks of Alan writing the book. He was quite surprised when I showed him the research. This mill was also the inspiration for Adam Smith’s metaphor for the invisible hand of capitalism and Dr Johnson held shares in it.”

In typically bold fashion, David Keenan’s recently published novel, Monument Maker, exists solely in no one genre or category, but dips a toe experimentally into all of them. Historical fiction rubs shoulders with sci-fi sections and many Pynchonesque themes abound– occult societies, the eternal recurrence of fascism, paranoiac conspiracies, transgressive art and artful transgressions.

David Keenan had this to say to the Quietus about the novel that took him ten years to write:

"I’m a total believer in form matching content, I think that is how you judge a big book, as to whether the content ‘demanded’ the form. I wanted to spend years working on a book that I would think about every morning and go to sleep wondering about at night. I wanted to be completely captivated by a fictional reality of my own devising, which is what Monument Maker is, the culmination of a ten-year obsession. I wanted to make a literal monument, the book as a great cathedral, and tomb, too, so it had to be monumental in-itself in order to fully manifest.

"The first big book I really fell in love with was probably Lord of the Rings, and I loved that whole idea of a lifetime of worlds being contained in one book. I have never been interested in those massive college boy state of the nation books that Americans like Don Delillo or even Thomas Pynchon write. Pynchon I read when I was young but would never go back to. I did love Infinite Jest and certainly its “heft” was part of its appeal, knowing that someone had been insane enough to write that.

"Honestly, I honour ambition, and hard work. That’s why I respect big books. I abhor ideas that big books are somehow “self-indulgent” or “pretentious”. It’s a way of keeping you in your place, of not getting too ambitious, of not getting above your station. And who, by implication, should we otherwise indulge; you?"

Although Keenan’s concept of structure is, by his own admission, looser than most (“I have little actual memory of writing it, it’s such a buzz when you have all these pages that are alive and that are speaking to other parts of this huge life work and you are literally in the midst of it”), structure is crucial, whether you are concerned with working within specific boundaries, or ultimately attempting to transcend its confines.

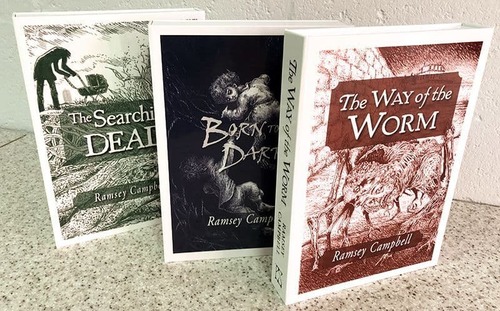

The English horror fiction writer and critic, Ramsey Campbell, more well known for his short stories and relatively short novels, had this to say in regard to his most accomplished work, The Three Births of Daoloth trilogy:

“It’s often said that the ideal form for horror fiction is the short story or the novella, since intensity is harder to sustain at novel length – but the novel may take on more themes and has greater scope. The secret is structure, not length. My trilogy (about 300,000 words) let me range across most of my life for experiences that brought it alive, and gave me space to deal with a variety of themes – social change, loss of faith and its repercussions, personal loss and the process of grief, the growth of the irrational and the dependence on cults – without ever losing sight of the supernatural and the cosmic. I find the long form generates an energy I seldom enjoy to that extent in writing shorter tales. Its capacity to surprise me in the writing is greater, and its ability to invent itself is hugely invigorating. I also think it gives the subconscious more room to create patterns and resonances and concealed themes while I’m consciously at work telling the tale. A tale must be as long as that particular tale needs to be, which is ultimately resolved in the rewrite. At its best, the longer novel offers great range and richness."

Trilogies, or books that otherwise divide into differently numbered sections, can be tremendously rewarding. The Canadian author, Robertson Davies (1913-1995), considered by some to have been ‘Canada’s greatest novelist’, accomplished a unique melding of narrative and symbolism in both his Deptford and Cornish trilogies. Written in a kind of magical realist style, also heavily influenced by Jungian theory, The Deptford Trilogy (1970-75) plots the course of the events which follow the impact made by a stray snowball thrown during the course of the narrator’s early childhood. In the depth of insight that he provides into his characters, and the mapping out of consequences along the full length of those lives, reading Davies’ work almost spoiled me for other authors, whose characterisations sometimes seemed shallow by comparison. The symbolic richness of his work, in which the images contained in a single small section of text might resonate throughout the parts that had preceded it, is extremely powerful.

The only other novel I am aware of that accomplishes a similar degree of placing the reader into a moment so highly charged with meaning that has been building exponentially from the very beginning of its text, is Roberto Bolaño’s masterpiece, 2666. Published only after Bolaño’s death, but assembled into five sections according to his instructions, 2666 tells the story of the search for the mysterious (fictional) author, Benno von Archimboldi. Arriving as it does only at the very end of the book, and especially coming after a grim section detailing the autopsies of murder victims from the town of Ciudad Juárez, the ‘Part About Archimboldi’ section of the book induces in the reader a dizzying sense of revelation. The moment where ‘Archimboldi’ hides inside the farmhouse hearth, reading Boris Ansky’s papers by candlelight, and the story-within-the-story is revealed, nestling at the heart of all the other stories, resonating throughout, and somehow beyond, the rest of the novel’s text.

Adam Levin’s Bubblegum (2020), is a hugely original contemporary long novel, with a part that clearly references 2666’s ‘The Part About The Crimes’ section. The book is set in Chicago, in a parallel/alternate present-day world in which the internet has never existed, but where an interactive ‘pet’ (possibly robot, or perhaps genetically engineered animal DNA derived) called ‘Curios’ or ‘Cures’ have played a central role in the public imagination since the 1980s. The protagonist, Belt Magnet, who also believes himself to have the ability to converse with inanimate objects, was one of the first adopters of a Curio and is now writing his memoir. Most of the newer Curios don’t live as long as Magnet’s, however, since most people see them as a non-sentient entities, and perceive no problem in "overloading" their Curios – killing them and enjoying the "pain-song" they sing as they expire. As entertainingly bizarre as the scenario is, the novel’s set up allows Levin the space to investigate the fetishisation of consumerism, the value of life over such mere objects and the appalling way humans treat non-humans and other humans alike, in our post-internet world, without ever referring to the internet itself.

Adam Levin had this to say, regarding the novel’s genesis:

"In early 2004, I wrote a twelve-page short story about a sad young man who converses with a swingset. The story was overwrought and cheesy. There were a couple aspects that I liked though. In the meantime, I adopted a Quaker parrot for reasons too complicated to describe in this space. Prior to getting this parrot, I’d never cared for pets, or for animals in general, and all at once there was this one that I, well, loved, which caused me to do a lot of thinking about animals and… love. Also, I’d been reading BF Skinner again, had come to find his approach more compelling than ever, especially when applied to verbal behavior, even more especially when applied to verbal behavior on social media. In sum, I imagined that I would take a lot of joy in thinking extensively about verbal behavior and pets and, because I can’t think well, let alone extensively, when I’m not writing fiction, I started writing fiction to think about verbal behavior and pets.

"What I thought to do to solve this problem — what I’ve always done when I’ve started a piece of fiction that I’ve ended up finishing—was come up with the worst and hardest-to-execute idea that I could. I looked through my folders of fragments and failures and soon determined that having a man who claims to have the capacity to converse with inanimate objects narrate a novel that’s set in a world enamored with pets that may or may not be robots was a sufficiently terrible and hard-to-execute idea. So I started writing Bubblegum."

In this case, the many peripheral details conveyed over the course of the novel’s 767 pages act upon the reader in such a fashion as to displace the connection with our own world and replace it with a feeling of existing in a parallel one where much is different yet much also remains the same. Whilst the metaphorical apparatus of science-fiction allows for a different perspective on our own existence, some subjects are more powerfully conveyed with a more direct and realist approach. One such example is Marlon James’s A Brief History Of Seven Killings. Here I’m going to pass over to the person who put me onto the book in the first place, Stav Sherez (winner of the 2018 Theakston Old Peculier award for crime fiction with his novel The Intrusions):

“Some long books feel so long you’re almost a different person on finishing than when you started. Others zoom by in one breathless rush of kinetic prose and immersive conspiracy. Marlon James’s superlative 2014 novel, A Brief History of Seven Killings, is such a book – a polyphonous punch to the gut and a cracking crime novel that uncovers a landscape previously untouched in fiction. It’s one of those rare books that’s both a crime novel and a literary novel, whatever those terms mean. Like any great novel, James uses a specific instance of crime – the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in this instance – to explicate, extrapolate and comment on a secret history; a history of a nation and of individuals caught in the crosshairs of time. The range of voices and POVs is staggering. The sheer imaginative force of language is mined to its full potential – a word stew that’s one part Joyce, one part Ellroy and three parts pure Marlon James. The rush of prose is intoxicating and exciting and restores your faith in the power of fiction to articulate fucked-up lives and fucked-up times."

A similarly weighty novel, capable of impacting violently on the reader’s consciousness, is Leslie Marmon Silko’s 1991 epic, Almanac Of The Dead. A powerful and complex tapestry of many interwoven lives that largely relies on a realist approach leavened with some powerful Native American magical and historical elements, the book offers little respite to the reader. Eschewing more linear notions of constructed time, the reader is dropped into scenarios which only come into sharper view as the book proceeds. The majority of the story occurs in the ‘present’, although prolonged flashbacks and mythical tales tied to indigenous knowledge are also an important part of the book’s construction.

At times, the dense collection of interconnected character narratives seems inescapably oppressive, as if the heavy weight of history is pressing against the characters themselves. When the indigenous Mayan revolutionary, Angelita La Escapia, first reads Marx’s accounts of “children who had been worked to death—their deformed bodies shaped to fit inside factory machinery and other cramped spaces”, she recognises the truth in those words and at the same time is utterly nonplussed: “She could have never imagined tiny children wedged inside the machinery just to make a rich man richer.”

Finally, to end on something more abstract, whose formal innovation is also a central pillar of its plot, Rian Hughes’ XX concerns an extra-terrestrial signal received at Jodrell Bank, and the efforts made to decode that signal by a group of computer programmers based in Hoxton. Much of the book is an extended riff on semiotics—the signs we use and how we define them, and also how they define us. Hughes’s background as an illustrator, graphic designer and typographer inspired an unusual degree of playfulness within the form of his first novel. Utilising many different styles of typeface and page layout, as well as a section affectionately composed in the form of a sci-fi serial with accompanying era-appropriate artwork, and an accompanying soundtrack composed by DJ Food, XX is an immensely fun book, which marries form to content in a unique and pioneering fashion. Hughes had this to say to the Quietus:

"The first long book I remember reading was Dune, around the age of 15. The length does allow a depth and scope a shorter novel doesn’t, and I remember being completely immersed.

"I had no idea how long XX might be when I started. I had a pretty clear structural map of it all from the outset, and knew the ground I needed to cover. I ended up writing the last few chapters twice, a year and a half apart, then editing together one version from the best of each. The book was written straight into Indesign, in the fonts and sizes you see in the final version. It wasn’t written in Word first, double-spaced, and then designed later, it was very much a case of seeing what it looked like as I was creating it — which I feel is essential for a book of this kind. I did edit out around 350 pages, as I was determined to keep it under a thousand. So the length was not so much a matter of choice, more a by-product of the kind of story being told and its graphical elements.”

To conclude, I would like to add that this article is not meant to suggest a rigid canon of works, but to merely identify some of the many different types of longer novel, including some I have personally enjoyed. Apologies to the many wonderful texts that I could have included, if only I had as many pages to play with as Bolano or Proust.