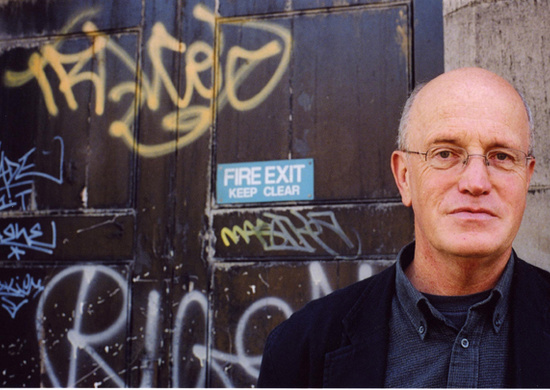

There are few journalistic sins that irk quite like following the phrase ‘needs no introduction’ with a lengthy introduction. As Iain Sinclair requires little preamble – particularly in these pages – I’ll keep this brief.

I meet Sinclair in the London Review Bookshop, where he is appearing to discuss, among other things, his new book 70×70. Unlicensed Preaching: A Life Unpacked In 70 Films. I say ‘among other things’ because it is rare that Sinclair is working on only one project, and his various interests wander densely intertwined paths. A series of seventy films – to reflect on his seventy years – screened across London form the substance of the book, but open other routes besides.

With Sinclair tonight in Bloomsbury are filmmaker Chris Petit and composer Susan Stenger. The former is a long-term collaborator of Sinclair’s. The latter has worked with him on several films; most notably Marine Court Rendezvous (2009), a complex filmic portrait of the eponymous St. Leonards-on-Sea apartment block.

This nonplace nautical building, spatially unmoored as the ocean liners whose form it apes, might all too easily serve as allegory for Sinclair. His writing is in constant motion yet anchored tight to place, returning always to the flow of his East London environs. Alongside 70×70, Sinclair is producing a book based on a walk around the London Overground, re-arriving at old locales and embarking at new ones. This, too, has a cinema mien: the fourteen-hour Gingerline journey he undertook was made in the company of another filmmaker – Andrew Kötting.

It takes less than two minutes before Sinclair leads me to a new – at least to me – London discovery. We head to the Truckles pub, tucked alongside the London Review Bookshop in Pied Bull Yard, off Bury Place. Despite innumerable trips to the shop, it has never occurred to me to see what sits behind it. Sinclair’s eye, luckily, is not so easily distracted.

I thought I might start by asking how you begin curating a project of this size.

It was really an easy project to curate. We were sitting around talking, and Paul Smith, who runs King Mob, said to me, ‘Would you like to pick seventy films?’ Everybody would like to pick seventy films. The process of how you do that fell into place: I decided I would just use it as a way of going back over all the books I’ve written, because I’d actually written seventy books, as well – conveniently!

I started to pick the films that were influential on how I was thinking and writing; whether they were good films, or bad films, or whatever they were. As the list built up I could see connections between different films; when I’d finished this enormous list I winnowed it down, and then Paul asked me to put in the films I’d actually been involved with making, as well. So it became a sort of double portrait of a life projected through films. It gives you a certain sense of a person in a city. In London.

How did you go about whittling down from that long list to a shorter one?

Just ones that took my fancy. And some of the ones I’d never seen, and was very keen to see: I picked films that I’d referenced but never seen, in the hopes that they would turn up! This turned out pretty well on the whole, because I saw some great films that I’d never seen before.

Were there new correlations you found coming out as you were putting these alongside your writing? What were they?

Essentially, things that could seem totally disparate would have a connection – either by theme, or by location. Sometimes actors had been in enormously different things. Eddie Constantine, the French actor, turns up in a film made by Chris Petit [Flight to Berlin (1984)] who I’ve worked with a lot, in Germany. He’s also in Goddard’s Alpha-ville (1965). He’s here, there and everywhere. It could pivot on any of those things: either by character, actor, theme, location. And my own obsessions. I saw my own obsessions reflected in the films I’d picked.

Did you find new things you hadn’t detected in your own work brought to the surface?

No, I don’t think I found new things in my own work. I found stories. An aspect of my work as a London writer was revealed.

There’s a woman coming to this [the LRB] tonight called Muriel Walker, who’s in her eighties, and she wrote to me — having read an introduction I did to a book by Alexander Baron called The Low Life — to tell me she’d known Baron.

It turned out that she’d run away from London as a young woman and gone to Italy, and got sucked in to doing this film with Anna Magnani called Volcano (1950), which I knew nothing at all about. I discovered the lovely story that it was set up because Magnani had been the mistress of Roberto Rossellini, who’d run off with Ingrid Bergman, and she wanted to spoil the film he was doing next, so she made this film on the next door island to where he was working. By accident, Muriel Walker was part of that shoot, and kept a diary of it. So it was a whole, wonderful, rich story I knew nothing about which emerged as a result of doing this project.

Can I ask how you chose what to show where?

I didn’t actually do that. There’s a guy called Stanley Schtinter who went with the list I gave and liaised with different people. We’d have discussions about where was suitable, like I wanted to show Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) so he arranged a boat trip… but generally, he made the connections and just told me where I had to go. I was running around wherever in London I was told to go that night.

Of course cinema is always specific. A novel you can take anywhere. Cinema always happens in a discrete place.

But, from the beginning, cinema to me had always been about making the journeys to where the films were being shown. I didn’t grow up in London, so when I started out in the early 1960s I actually learnt my way around London by finding how to get to The Everyman in Hampstead, The Rio in Dalston… the first time I ever want to Dalston was to see a film at the Rio. Gradually a map of the city emerged which was based entirely on the journeys to find the cinemas. And then those journeys became part of the experience of seeing that film.

You have that lovely quotation about ‘chamber cinema’; was it odd to then go in to these very public spaces? The Barbican [where several of the films were shown] is such a huge institution.

Yes, it was quite an odd experience to go from somewhere where there were half a dozen people – or less – to a big public space like the Barbican. But the Barbican came right at the end, so that was quite nice; it seemed like, after having been out on the road in a lot of circus tents, finally getting into a museum, you know? The curation became a curation rather than a guerrilla exercise. Some of Stanley’s best ones were just shown in vans, on the street, or in a shop window, so that you hardly notice the thing was going on – just pitching it anywhere. They were so invisible that they hardly registered. But they were there, in the city.

I think it really changed my sense of London in some ways. I hadn’t been out to somewhere in Hammersmith, or the cinema museum down at the Elephant and Castle, for years. Getting there was like seeing a new London, with a new audience. I’m so bedded into East London now, having lived there for so long. It was great to be taken out of my comfort zone.

When you say you saw new things; was that just in terms of visiting new locales, or was there another aspect to the city in terms of its social geography, or…

Yes, I think every new locale is a new story. Spending a day around the Elephant and Castle — it’s a different city to spending a day around Dalston Junction. It looks theoretically the same, but actually the way people move, what’s going on inside the buildings, how the developments are occurring, is very, very different. You don’t really appreciate those differences until you spend time in a different place that’s outside the zones of what you know.

May I ask about the Overground? Because I also live on the Overground route…

Where?

By Whitechapel.

Okay. Right. Has that changed your life at all?

Well… less so around Whitechapel than, I suspect, around Haggerston.

It’s changed mine enormously, in a sense. It’s so convenient that I tend to make journeys that reflect on the railway rather than journeys that I need to make. I wouldn’t have thought of going to Clapham Junction if I couldn’t just jump on this train and get to Clapham Junction. I wouldn’t have gone to Willesden Junction, which proved to be very useful, because I got a better sense of Leon Kossoff as a painter. He’d done some fantastic paintings of Willesden Junction but I didn’t really know Willesden Junction.

I think the Overground railway is a bit like the cinema project in that it curates. It curates a London of disparate elements. What relates Denmark Hill to Finchley and Frognal or Camden Town to Shadwell? They are now an organic identity. And sitting on this train is like sitting in a cinema. You’ve got this screen, and the landscape changes. Patrick Keiller writes that as being the view from the train; that is, really, a form of cinema. I really believe that walking is a form of cinema, and being on a train is a form of cinema, and having the excuse to stop and go to these venues and see some wonderful movie enhances that experience.

The two projects were going on concurrently, for me, and they went backwards and forwards into each other. Because I was doing the work with Andrew Kötting, a film maker who I’ve collaborated with, and him telling me the stories of how he got interested in cinema was exactly the process of me investigating London the first time, when I lived in Brixton and went to film school there. In fact, the Overground trip took us right through Electric Avenue – I know the train doesn’t stop there, but when you’re following the railway the next stop is in Clapham North, I think, and that meant walking through Electric Avenue, where I’d been to film school. So everything meshed.

London is fantastic for inviting these coincidences.

Yes. London is a network of complete nexuses, coincidences, overlaps, references, people you meet telling you about books or films or whatever you haven’t seen. It’s a series of collisions in that way, and that’s what makes it exciting.

Moving on to the book, can I ask you about the title, because…

Yes! [laughs]

… because I think it’s a wonderful, witty title, but there also seems to be a tension registered in that.

There is a certain tension in, well, the numerology of it, first. The ‘70×70’ makes it feel epic and also absurd. Pomp. And the ‘unlicensed preaching’ is this sense that to bang on about films and cinema in a substantial way in this day and age means that you’re really out of your own period. It’s become something else already.

And then it simply was a life unpacked, through film. And is that good or bad? The twentieth century was the century of film and after that, it’s gone. It’s now something else. There’s a kind of retro-y buzz to certain elements of it, but essentially people do that [Iain gestures to my recording device]. The screen experience which was so exciting… what was exciting was that you couldn’t get these films anywhere else. If you wanted to see a strange film by Buñuel you absolutely had to go, that day, to the National Film Theatre in Hampstead or wherever it was, and make that journey. If you missed that day it wasn’t going to come up again. That was it. It was a one off. It was very exciting.

Whereas now you can actually pretty much find anything just like that.

Will Self says film is ‘atomised’ now. That’s the term he uses.

I think that’s right, yes.

Do you agree with his idea that film and the novel have been propping each other up? That they’re now dying together?

No, I think the novel is different. Because the novel was going strong long before film came up. Film bastardised theatre, originally, before the novel. Then there was the period where film propped itself up by endlessly lifting novels, and basically aborting them, or changing them into something else. That still goes on.

But I think the novel’s got a completely independent existence. It’s also challenged, and has to come up with completely new forms, but I’d put film more with the motor car. The age of the internal combustion engine is also over: it’s still around, but it’s redundant. Traffic is locked. We don’t need these things any more; it’s too expensive, the requirement to get the oil causes political chaos and wars. The car, which created forms of cinema – the road movie and the using of the screen of the car as a thing, which were very symbiotic – is redundant. They’re both finished. Cars haven’t admitted it yet; film kind of has. It’s gone into ever more grandiose, computer-generated, 3D, fantasy versions – to make it something you can’t get on a device easily, just to try and persuade you to undertake this experience.

But I’ve found that even with big, mainstream things, if you go to a screening there’s only six people there. It feels just like showing these really obscure films I was showing; there is not that mass audience. When film was at its peak in the 1930s, the experience of it was continual. 1:30 ‘til 10:30, it was going non-stop: feature, second feature, news, cartoons, bla bla bla – the whole thing was a complete world. Chunks of London were colonised by this experience. Like Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010), that 24-hour experience – cinema was like that, and now it’s fragmented. There’s a glimpse here, there’s a glimpse there. You don’t see whole films; you just see the best bits. It’s quite interesting. But the novel, which is to do with voice, and to do with an interior experience and telling stories, I think although it’s become a very specialised form, it’s still surviving.

The shop we just walked out of is not unlike a Victorian shop. I mean, it’s smoothed up, and you can get coffee or whatever, but basically the same principle goes on. There are people around here who like to read books, and go in there and inspect the wares and choose something. There are endless people making them. Whereas, I suppose, everybody is making film; but it isn’t actually film. It’s just a registering of something which may never actually be accessed. And the sheer quantity of imagery which is now being banked up, which no-one really looks at, or edits, or deals with; it’s terrifying. A tsunami of imagery.

This seems to be something your own film work plays with.

Well, yes. All the things I’ve done with Chris Petit were really all to do with the last days of that kind of film, and accessing what happens when the memory banks break down; when the film fragments and you’re trying to represent important cultural figures who are in danger of being erased, and it’s not a fiction, and it’s not a documentary, it’s a sort of no-man’s land. I’m very interested in that theme.

Can you talk a little about Marine Court Rendezvous? This film you’ve done about St Leonard’s on Sea. I read your Guardian piece from a few years ago on the building…

It’s a fascinating building.

It’s tremendous. And it strikes me that there are some things between what you’ve been saying about the motor car and about 1930s cinema, that difficulty of approaching modernism and modernity, that are also in this building, and in your film.

Very much. The building was a 1930s building, from the time of concrete, and it was built to look like an ocean liner. It was separate from the landscape that contained it. They pulled down a lot of Georgian houses to make this big brutal lump of concrete that looked like a boat. The idea was the people who went there didn’t have to engage with the town. They had their own tunnels underneath that brought you out onto sunloungers.

Then of course war came and that all went belly up; and by the time I knew the building, it was full of these flickering lights of TV sets. You could see it from outside; there were people watching films. I got the sense it was like a beehive of old movies, endlessly playing to people who are either dead in their rooms — or even empty rooms.

So Marine Court Rendezvous grew out of that idea, and was done as an installation. We had twelve screens that went right round the room. There were these panels on each wall, three big panels on each, showing changing aspects of the building. And we gradually let sequences infiltrate from Niagara (1953) and Tarnished Angels (1957), which is a film about flight, about a woman who parachutes out of a plane in her dress. Niagara is Marilyn Monroe with endless water. I had the idea that these rooms were just full of these images of endless, falling, crashing, flying, waterfalls – and we made this construction, which was also beautifully soundcrafted by Susan Stenger.

Then it became a live performance as well, in the gallery. The screens were playing, but the woman who was in the film actually came through a door, with the screen, and became a physical presence. It was interesting in that it was sort of post-cinema. Part installation, part film, part memory of film, part comment on the building, which I thought was like The Shining: these huge, empty, endless corridors. It’s like madness. It’s that sense of addiction; it’s that sense of modernism being out of its time. In that sense, the book is a sort of by-product of that building, and that whole idea of architecture and cinema being related.

People have called your poetry neo-modernism, and spoken of you as someone who has taken up this legacy of modernism.

Yes, I think that’s fair. My influences were classical modernism, but the classical modernism of Joyce, Pound, Wyndham Lewis and so on was very much looking back to classic Greek models. I was much more interested in late modernism, responding to that, than post-modernism, which was being ironic and camp and treating everything as being slightly unreal. Pre-digital, really, in a sense. I was the tail end of a long tradition as I saw it, and was trying to write in that way, but with the understanding that the moment has gone. So it’s rather like the Marine Court building; which has got concrete rust, and it’s rotting away, but it’s got a real patina of something special and interesting. And submerged. That’s kind of where I was writing from as a poet.

And the idea you could have the freedom to blend prose and poetry; documentation, lists, letters, a lot of quotation from film. I think that’s the other big modernist thing, is it’s based on quotation: from The Waste Land, which is just based on this series of voices and echoes, to the way that film works. Goddard, endlessly referencing, cutting up other people’s films – he saw this as being the classic heritage of cinema.

Fantastic. So fantastic. I suppose the only other thing I wanted to ask is a slightly glib question: if you were asked to do this with seventy books, would you…?

[Laughs] Well, it’d be very interesting to do that the other way around. To go to my favourite films and see which books are referenced. I really would have no idea! That would be, in a sense, more interesting to me, because I slightly remember the films that I’ve called upon in the various books, because I’d written about them and I’d chosen them. But if I went back to these films, and then went to see which books were referenced… I’d have no idea. That’d be really, really interesting. And then I’d add in books which I was reading, importantly, when I was making the various films myself. And the books we were talking about in the cutting room. And that would make another list… great idea!

Maybe someone at the Harry Ransom Center…

Yes, if someone gets bored, when I’m ninety or something, do that. But it’d be a very nice mirror image of this, and I don’t know what the answer would be. Let someone do it! Get a research student to go through all these things.

There’s a doctorate in this.

Yes, there’s a doctorate there, definitely.

70×70. Unlicensed Preaching: A Life Unpacked In 70 Films is out now, published by King Mob in association with Purge and Volcano publishing