If you believe the naysayers and doom-mongers of the music industry commentariat, record labels are like the music-selling equivalent of the last dodo, running haplessly across the Mauritian rocks in a vain attempt to escape the bullets and spears (e.g. modems and hard drives) of their human foe. Yet a read of Richard King’s How Soon Is Now? is a lesson in the dubiousness of that opinion.

A chaotic tale of inefficiency, ideology, falling-out, in-fighting, drugs, bankrupcy and booze, it suggests that there was no real golden age (in financial terms if nothing else) for the independent record label during the late 70s and 80s. Instead, a group of passionate, intelligent, rightous and, at times, rather unhinged people somehow managed to stay above water long enough to release some of the the best music of their time.

Looking back at the period so well covered by King from the strange time of 2012, it seems that we’re potentially in a more stable time for the independent label, with much of the dead wood and unprofessionalism cut out, and perhaps less cocaine off the graphic designer’s easel. And after all, those 18 million Adele albums were sent out into the Tescos and Amazon warehouses of the world by the Beggars group. Who knows what a follow-up to How Soon Is Now? would see the label spend those enormous revenues on…

In the extract below, we hear about the rise of Paul Smith’s Blast First label, initially given a distribution deal to release Sonic Youth’s Bad Moon Rising by Rough Trade, with whom they fell out before hooking up with Daniel Miller to become Mute’s "awkward squad" and signing the likes of Big Black and the Butthole Surfers.

Luke Turner

How Soon Is Now?, by Richard King

Stereo Sanctity

Sonic Youth’s second full-length album, Bad Moon Rising took its title from a Creedence song, which, along with its scarecrow-on-fire sleeve, signalled a move away from the bands art space roots towards a deconstruction of the John Carpenter or Stephen King version of a primitive-gothic heartland America.

The record left the New York grid for a trip down forbidding back roads. The title of the track ‘Ghost Bitch’ was a reference to the Native American Indian relationship with pioneering settlers. ‘I’m Insane’ and ‘Society Is a Hole,’ both coloured by the burnished open-wound textures of the band’s guitars, turned the record into a raw meditation on the corn belt. The album’s closing track, ‘Death Valley ’69’, a duet with Lunch, referenced the Manson murders. The cult of Charles Manson would become a trope that would spread through the American underground in the Eighties and beyond to the point where Guns N’ Roses would cover one of his songs. In 1985, before Mansonphilia took hold, ‘Death Valley ’69’ was a shock reminder of the unwanted houseguest at the macrobiotic dinner party. The song was a throw-down to the baby boomer settlement, which, in typical me-generation fashion was beginning to navel-gaze at its lost innocence and ideals through such pieces of retro-analysis as The Big Chill and Running on Empty. The tapes Moore sent to Smith had a depth of texture more akin to cinema than the scratchy sounds of Manhatten performance spaces.

"For somebody who’d loved and absorbed a lot music, it was quite clear to me that this was an actual, living Velvet Underground," says Smith. "It just hit me incredibly hard emotionally." Convinced of the need to get the record a European release, and with an evangelical zeal that would sustain him until the end of the decade, Smith hustled every contact he had in the hope of finding Bad Moon Rising a home.

"First of all I took it to DoubleVison," says Smith. "Richard said, ‘Well, it’s guitars… it’s rock & roll. We don’t do rock & roll,’ so I trotted round various other labels, pretty much actually every independent label at that point, including Mute, and nobody was interested." Met with indifference Smith resorted to doorstepping the staff at Rough Trade at every opportunity, turning lunchtimes in the Malt & Hops into lobbying sessions on the merits of Sonic Youth. Richard Thomas, another regular at the Malt & Hops ("It was," he says, "the nearest I ever had to an office.") worked with Smith from the start of Blast First. In less than four years Thomas and Smith promoted shows that saw Sonic Youth grow from an audience of 200 to over 5,000, but such a quick trajectory for the band was initially far from certain. "Pete Walmsley, who was in charge of label management at Rough Trade, offered him an M&D deal", says Thomas, "to basically shut him up more than anything else."

"Peter Walmsley said, ‘You get the rights, I’ll make the records, let’s talk about something else,’" says Smith. "He always wanted to talk about football. I’m not interested in football but there we go. The people that ran labels were all sports failures, and the people who ran the distribution side of it were all sports interested. We wanted to talk about catalogue numbers and Can out-takes, they all wanted to talk about how Arsenal did or whatever it was."

Smith’s ambitions consisted of little more than seeing Bad Moon Rising released. In his off-the-cuff negotiations he was, however, becoming Sonic Youth’s semi-official representative, manager, booking agent and now their one-man record company – a position that would become increasingly draining and problematic. "Walmsley said, ‘What’s the name of the label?’" says Smith, "and I said, ‘What label?’ and he said, ‘Your label’… I actually hadn’t thought it through to the point of having a name for the label. I’d always been a bit of a Wyndham Lewis fan: ‘Oh, this is good, this is all about warm winds from America keeping England mild… here’s Sonic Youth making a bit of a racket’… a bit of English irony. But having a record label wasn’t in my plan, well, more than that – I didn’t have a plan."

As an example of the opportunities Rough Trade still afforded anyone with a degree of enthusiasm and a tape of new music, Smith’s arrangements with Walmsley were among the last of the off-the-street Rough Trade deals. Simon Harper, who as a label manger was negotiating the increasingly difficult complexities of the company’s structure, could sense a wave of enthusiasm building around Smith and his ability to turn lunchtime drinking sessions into strategic meetings for the coming counter-cultural revolution, one that would be soundtracked by the white heat of Blast First; it would be, as Smith christened a label compilation he released four years later, Nothing Short of Total War.

"Paul Smith was a remarkably social man," says Harper, "and a culture then existed of throwing ideas around in a very social environment, namely the Malt & Hops." It may have been pub talk turned into an improvised release schedule, but within three releases Blast First’s relationship with Rough Trade had already faltered. "Blast First’s first release or two was through the record company," says Smith, "’and then we got kicked off after the cover of Sonic Youth’s ‘Flower’ offended them.’ The sleeve of Sonic Youth’s ‘Halloween’/’Flower’ 12" was a smudged black-and-white photocopy of a topless model in a downward-gazing pose. Alongside the image were the song’s lyrics in handwritten capitals: "Support the Power of Woman/Use the Power of Man/Support the Flower of Woman/Use the Word:/ Fuck/The Word is Love" At the bottom left of the sleeve is a single word, ‘Enticing’. The sleeve was a copy-shop approximation of the kind of sleeves Raymond Pettibon was producing for the SST label in California: illustrations of blank-eyed characters of SoCal suburbia inhabiting empty spaces, both physical and mental, that despite their best efforts, consumerism and sex couldn’t fill. What made sense in the context of the American underground, where such signifiers formed part of the bands’ running commentary on their surroundings, had an equal resonance with Sonic Youth’s connections with the Artforum sensibilities of New York galleries. In the context of Collier Street, it was given short shrift, dismissed as either a piece of New Yorker know-it-all provocation, or the kind of straightforward exploitative misogynist artwork that belonged on a heavy metal album. "I remember passing through big debates about the Sonic Youth ‘Flower’ 12", says Cerne Canning. " ‘I’m not fucking working that record’, that kind of thing. There was a lot of that which I must admit I quite like, some of it was time-wasting but there other elements, which revealed people’s passion for things. Without being misty-eyed, we live in a blander era. I quite like the fact that people felt strongly about things and felt empowered to kick up a fuss."

The discussions at Rough Trade were enough to prompt a news story in the NME, in which Travis was quoted as saying, "It’s not that the naked form is sexist in itself, it just looks like another sexist piece of shit. We don’t want to be a party to their muddleheadedness.’" Smith relished the air of provocation starting to form around Blast First and the confrontational sound of its releases, and sensed that Travis, in such an act of censorship, was now being left behind; having just received a tape of Sonic Youth’s next album, Evol, Smith did, however, need to quickly find a way of maintaining enough good will to ensure both its release and Blast First’s momentum. With zero budget for anything resembling promotion or marketing, Smith used such episodes as the ‘Halloween’/’Flower’ fracas to his and Blast First’s advantage. In deciding to work with Liz Naylor and her sister Pat, Smith found the perfect foils to maximise the label’s reputation for the ornery and unconventional. The Naylors were wholly unconvinced of the need to respect the orthodoxies of the music press. They also disliked nearly every journalist they had to work with. Blast First nevertheless received excellent coverage. "The opportunity to put out the records was one thing," says Smith. "The opportunity for either of the Naylors to be involved, due to their loathing of young male journalists and their sexual orientation and everything else, just created a whole other way of operating."

Smith also built a power base among the more disenfranchised members of staff in the Collier Street warehouse who were far more at home with the Blast First work ethic of inebriation, amphetamines and loud confrontational music than with the target-led structure of the critical path.

"One of the secrets of Blast First’s success, certainly Sonic Youth’s success, was the fact that I invited all the people that packed and unpacked the records," says Smith. "Those were the guys who would stay an extra hour to ship your records out so all those people were on the guest list. When Sonic Youth played at ULU, which is 800-capacity, there was a guest list of 270. The warehouse couldn’t get into a fucking Woodentops gig for love nor money, not that they’d necessarily want to go, but nonetheless…" As Rough Trade grew more professional an us-and-them culture was entrenched within the building and Smith was becoming something of a union leader for the warehouse staff.

It would prove a temporary rally. The professionalism that he railed against would never take hold at Collier Street but in the glass-fronted offices of Manhattan, Smith would come face to face with the realities of the American entertainment business. "It sounds incredibly simple-minded because it was incredibly simple-minded", he says, "but I thought, I don’t really care if the third accountant or something can’t get in with his six faxes to see Sonic Youth, although later on I would learn the lesson that that would be a good thing to have on your guest list."

"Most of Rough Trade ran on speed," says Smith. "I think I only once mistakenly opened the photocopier and put some paper in without looking, to hear about twenty people go, ‘Oh my God,’ and me go, ‘What, what? – oh, sorry guys.’ I think I went out and bought them another gram. That’s how that how place ran, downstairs ran on drugs and alcohol, upstairs ran on camomile tea and some idea that they were doing something." While Smith’s metabolism ensured he was sufficiently wired without the need for anything other than a regular pint rush ("God knows what it was like walking anywhere with Americans then," he says. "I’d always be two blocks ahead thinking, where are they, we’re losing valuable pints time here.") He was still winging his every move with no base or structure other than whatever chair and telephone he could quickly occupy within

Collier Street, bobbing between offices, quickly pulling strings and favours when the powers that be were looking the other way. "Because I didn’t have an office in London, or anywhere else for that matter, I used to squat, either in production, which was Richard Boon, or just lean over and make a few more phone calls on Pat and Liz’s desks. People forget about how you couldn’t communicate at that point – telex was a popular item – people would come and say, ‘Oh, look, the telex machine.’ I’d do that and one day I was given a phone, saying it was Daniel Miller for me. I thought, oh, Daniel Miller, electronicy man."

Having left the Depeche Mode producer’s chair behind, Miller was interested in expanding Mute’s operations to include other labels. Alongside Blast First, Miller would add Rhythm King and Product Inc. to the Mute portfolio. Intrigued by a Head of David single Smith had released, Miller asked him over to the newly purchased Harrow Road offices which Miller had bought with the proceeds of Depeche Mode and Yazoo but which were run on a make-do-and-mend budget.

"I had to trot over to fucking west London to go and see him," says Smith, "and I met the Mute Beauties, as we knew them at that point – he had all these girls working for him. They weren’t like the 4AD super elegant girls, they were heavy-duty party girls who were looking at their watches, waiting for Dan to leave so they could rip it up. Their desks were all made out of doors on trestles as opposed to 4AD where everything had obviously been designed by Ben Kelly and money had been spent on furnishing." Miller felt that the Herzog-style tunnel vision he had applied to Black Celebration had left him behind the times. "I wanted to work with people who were starting to put out records that I didn’t quite understand," he says, "not to recapture anything, as Mute was doing fine, but more to work with people I found intriguing, and with music that I couldn’t initially work out."

Miller, having given a platform to three new labels, was fully aware of the risks he was taking in letting such a disparate group into his operations, part of which involved factions arising in Harrow Road, as each of the labels competed over ownership of the zeitgeist. "Blast First became the Mute awkward squad," says Miller. "It irritated me occasionally, but I put up with it. There was definitely hedonism everywhere but I felt like there had to be one person around that wasn’t off their heads."

Given a free hand by Miller, Smith was starting to feel like he’d landed on his feet. "We were not interested in integrating with anybody at that point," he says. "What I wanted was people I could argue with passionately, at length, in the pub ideally, about what we were doing and why we were doing it." The momentum of the label’s release schedule and its reputation for uncompromising volume, speed and aggression, along with the fact it was a UK company specialising in American music, gave it a cachet and outsider image that made it almost instantly iconic. John Peel, who booked all of the label’s bands for sessions whenever they were in the UK, in an unguarded moment of effusiveness declared Blast First the most important label of the age.

"Days would go by without sleep on the incredibleness of the whole thing," says Smith. "There was always one more fax, one more phone call… I was completely driven, and I actually didn’t realise how fucked-up driven I was until it stopped. Bad Moon was like a starting gun and I was like, ‘Whoa, fuck, OK… nobody else around’…"

Smith’s signings were a by-product of the intensive networking undertaken by Sonic Youth, who, having signed to the West Coast SST, had broken away from New York and were sharing cross country tours with a peer group of like-minded bands on a zero budget. Moore in particular had an inquisitive enthusiasm that made him something of a spokesperson or statesman, regularly encouraging and boosting many of his contemporaries. As well as a charismatic front person he was also one of the finest A&R men of his generation, and Smith was made aware of his energies and ambassadorial instincts instantly.

"One of the first things Thurston said to me – in fact I think it was the first thing he said to me when I met them at Heathrow – was, ‘Oh no, you’re just like us,’" says Smith. "They had been hoping a businessman would meet them because he’d brought this list of twenty-two bands that had to be signed immediately. Thurston was like, ‘You’ve got to put this out, you’ve got to put this out.’… The ones that I met that I liked then I put their records out, the ones that I met I didn’t like, well then, I didn’t."

The first contact Smith made with anyone on Moore’s list was Steve Albini, whose band Big Black was a rendering of the sound of power tools in human form. "I ended up in Chicago with Sonic Youth," says Smith. "They were playing at the Metro and there was a xerox poster of Steve in the box office saying, "Do not let this man in under any circumstance," and I remember thinking, that’s funny I wonder why, and then an hour later walking a couple of blocks down to some Mexican restaurant with Steve and Sonic Youth and people on the other side of the street yelling, ‘Fuck you, Albini, fuck you,’ and screaming at him from the street and I was thinking, this is an interesting little man, what’s his thing?"

Formed by Albini while still at college, Big Black use modified guitars and a drum machine to create a brutal, electrifying primitivism, the aural equivalent of their songs’ subject matter: abattoirs, serial killers, alcoholism and paedophilia, one loud confrontational song after another taking the listener into the heart of a highly dysfunctional Midwest. Albini, a journalism major, would never feel the need to defend his motives but if pushed would explain he was holding a mirror to society, using a similar reflex to Genesis P-Orridge’s defence/thesis of Throbbing Gristle’s material.

In August 1986, just two weeks after the C86 week at the ICA, Big Black made their British debut. The drum-machine-led assault of the band on a British audience, which saw Albini shake his wire frame into contortions when he sang about psychoses and sadism as the trio lined up in a row playing their guitars in anger, could not have been in a more marked contrast to the performances of the previous month at the ICA. Big Black played at an incredible volume, the kick from the drum machine reverberated in the audience’s chests giving their air of confrontation a physical dimension. As Smith had noted in Chicago, even in the tightly knit mutualism of the independent network in the States, Albini was a divisive figure. Either dismissed as sensationalist and tasteless or embraced as a fiercely loyal operator with his own distinct moral compass, he split opinion easily. Liz Naylor was on hand to liaise with the band in Smith’s absence and found herself in the former camp. "It was so loud and so sweaty when they came over and I thought, wow, pretty impressive," she says, "and then – I don’t know why, I’m not schooled in feminism particularly – but Albini came over and I remember going for a drink with him and he was teetotal, and he was really fucking nerdy and pervy; he was really provocative and unnecessary. He was just this sort of virgin geek."

Albini’s reputation for no-compromise and not suffering fools gladly was met by Naylor’s own rigorous indignation. Sensing a bully at work she flatly refused to deal with the band. "I just thought he was an idiot and I then just thought, I’m really not fucking doing this. I remember that being an issue between me and Paul. It wrangled everything up." Blast First released Big Black’s debut, the pummelling and concise Atomizer, along with a semi-official live vinyl album, The Sound of Impact, in 1986. When Big Black staged a return visit the following year the band played to rapt audiences.

"If Big Black had stayed together, they would have been the biggest band on Blast First," says Smith. "Absolutely no doubt: they had the stadium, anthemic, simple-minded power and performance to be huge. I’m not saying Steve wouldn’t have been a very, very unhappy human being as a consequence but they really would have been massive." For Atomizer‘s follow-up, Songs about Fucking, released just six months later in spring 1987, Pat Naylor, who had agreed to work with the band but on her own terms, issued a highly individual press release. "It was on one A4 sheet, of which three quarters of the page was saying what a shit weekend she had, ’cause Derby had lost – she was a big Derby County fan – and the last thing was, ‘Oh, by the way, there’s another great record out on Blast First by Big Black.’ That was it, and that got reproduced in the NME verbatim."

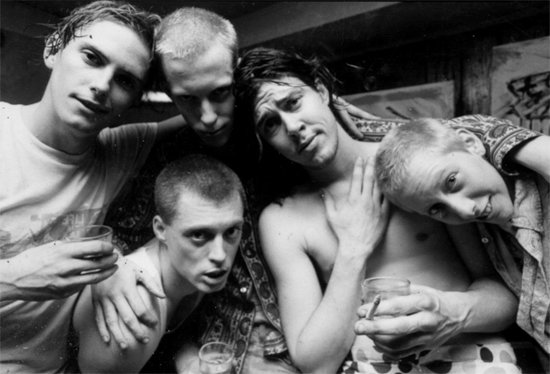

Blast First had turned into a record-company version of its bands: alive with heated internal debates resulting in a playful and antagonising set of gestures, which the acts on the label largely appreciated. Working with bands with a road-hardened punk-rock work ethic, the label had a lean and focused release schedule that gave it a clear definition. In 1987 Smith released Locust Abortion Technician by the Butthole Surfers. The Buttholes had dirt-bagged across America, operating out of a decrepit station wagon and putting on shows that were a form of performance anti-art wherever they could find a booking. A panhandling, Reaganomics version of the Merry Pranksters, the Buttholes honed their act to include gruesome back projections of circumcisions and chemical testing, overlaid with a strobe-heavy lightshow that made for a disorientating sensory experience. In front of this retina-burning overload the band’s two drummers would pound out a merciless beat over which guitarist Paul Leary would dispatch bludgeoning riffs.

Onstage the band were a partially clothed set of hallucinating dervishes. The result was dark, psychedelic chaos: a bad acid test. Smith had first seen the band in their natural onstage habitat at a festival in the Netherlands where Sonic Youth were also on the bill. Standing at the side of the stage Smith was confronted by the looming, shaking, six-foot frame of the Buttholes’ vocalist Gibby Haynes. "The first thing Gibby ever said to me was, ‘What time is it, man?’ says Smith. "’What time is it?’ Five minutes later he came up to me again, ‘What time is it now?’ They needed to know when to drop the acid, so that it came on to the maximum when they went onstage. They were like, ‘Who’s got the paint, who’s got the bandages…’ Gibby was putting pegs in his hair and then binding his head up minutes before they went on stage and then blundering on in this nonchalant kind of fashion and this… this enormous metal riff, you saw that and thought, holy fuck, here’s another one of those bands…"

Visit the Faber online shop to purchase the full How Soon Is Now?