Heather Phillipson is an artist working across video, sculpture, sound, text and live events. She exhibits internationally, with recent venues including BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Whitechapel Gallery, Flux Night Atlanta, LOOP Barcelona, Kunsthalle Basel, and a new video commission for Channel 4. She is also a Gregory Award-winning poet, was selected as a Faber New Poet in 2009 and her first full-length poetry collection, Instant-flex 718, appeared from Bloodaxe in 2013.

In December 2012 she published NOT AN ESSAY (Penned in the Margins), which is commonly referred to simply as ‘her text’ and may be considered a bridge between her two practices. It is composed of what appear to be prose-poem fragments that refuse to be pinned down to any one mode or genre. The writing has a frenetic energy as it interrogates the body as-object and how we situate ourselves in various private / public spaces: the swimming pool, night club, cinema, cemetery, between repetitive beats or syncopated phrases, in pyjamas or ‘subjectively awful trousers’; between the pauses of a rail announcement; from behind the facades of our faces – ‘the head’s interior’. The text is probing, provocative and tactile; intense, witty and beguiling by turns.

How did NOT AN ESSAY come into being?

Heather Phillipson: Rapidly, in winter, with a sense of crisis. Someone, and I wish I could remember who, said that art is like a crisis – something that provokes us to remember or to imagine. The genesis of NOT AN ESSAY was saturated with mis/remembered and actual/virtual encounters – a feeling of unassimilable experiences that needed the back-bone of syntax, text-blocks and pages. Stuff of the gut, stuff of fantasy, sensations in the eyes and legs – a creeping sense of paranoia, surveillance, segregation, objecthood. Being meaty. Coupled with an urge towards language. In a way, it really did start at the beginning, just as the text opens, with a pig’s torso in a butcher’s window, or the idea of one – the decapitated pig as a representation of meat-space – the proximity, even ingestion of other bodies. The body as a limit-point, but also an interface. Penetration, digitisation, brutality, empathy, consumption, negligence, images. The need to answer back to all this.

It is also arguably not a book of poems – how did your approach vary to that of your poetry collection, Instant-flex 718?

HP: Arguably! I don’t know what it is, and I don’t really want to. Definitions can be so tedious. Marianne Moore said something like: my poems are poems because nobody knows what else they could be. I keep coming back to this negative state – unseating criteria. It feels apposite and productive. The text declares outright, with caps-lock on, that it’s not an essay – but it over-protests. The implication is that it could be. The negative necessarily indicates its opposite. I like that you’re making the same case for its status as poetry – it’s not a book of poems. Or is it?

Superficially, my approach to writing NOT AN ESSAY was very different to that of Instant-flex 718 – the former unrolled in weeks, the latter over years. NOT AN ESSAY is sustained – it’s a compressed chunk of thought, whereas Instant-flex expands across many chunks of thought. But, fundamentally, they’re activated by similar preoccupations and tactics – assemblage, say, and accidents/conflicts, trying to get the maximum tension between parts. Also, notably, digression – a way to avoid the shortest route between two points. There’s a lot of avoidance that goes on in both.

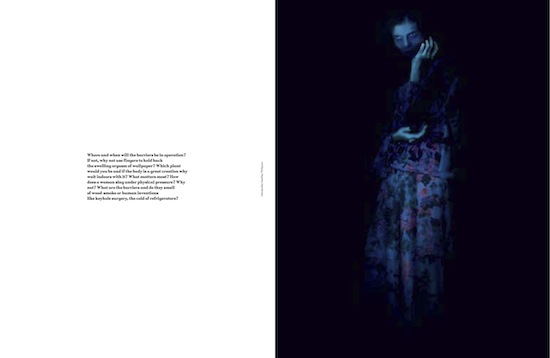

You’ve also published ekphrastic ‘introductions’ to fashion photos in AnOther magazine – which made it into Instant-flex 718 as stand-alone poems… How do you think the publishing context impacts on the way we read a piece of writing?

HP: Decisively and ambiguously. The artwork/poem’s context is both its destiny and its escape route. Of course, the question of context is one that’s been asked by art and artists since Duchamp and beyond – what happens if I put a human turd in a gallery (Piero Manzoni)? what happens if I put an enormous, inflatable dog turd in a field (Paul McCarthy)? In the artworld, it’s also bound up with notions of ‘value’. As an artist, one develops a healthy mistrust of context.

Inevitably, the socio-cultural context is crucial, both politically and in terms of how/where the artwork is encountered. A poem read alongside a high-fashion photograph prompts multiple associations that are anywhere but in the poem. The poem is co-opted by the bigger narrative – not only the fashion ‘story’ but also the commercial story – its place in a trajectory of desire and consumption. How much the poem resists or submits to this context is partly up to the poem, but it’s still the backdrop (foreground) – the prism by which all interpretations are refracted. Transposing the poem into a book of poems is a more familiar, less fraught manoeuvre, but it’s not necessarily preferable. There’s something potentially destabilizing about inserting poetry where it doesn’t quite belong, like an inflatable dog turd – it might highlight or perforate the landscape, or get impaled on some rocks, or just blow up differently. Regardless, wherever it goes, the poem confronts its physical constraints: the spatial enclosure of the book, magazine, screen etc. – scale, roominess, texture/sheen/tooth, typeface tics.

But, this said, the important thing is always the time and place that the art/writing constructs – it might depend on the time and place in which exists but, ultimately, it might also leave all that behind.

Your work handles a lot of theory but never alienates the reader with academic language. What is it about the essay as-form you feel you’re challenging?

HP: I’m not sure I know exactly what an essay is, other than a try-out, in the etymological sense. So, in that respect, the text doesn’t set out to ‘challenge’ the essay form, but just to stand with one leg on its terrain in order to look elsewhere. It doesn’t say ‘this is what I see’ but, ‘is this what I see?’ It wobbles.

One thing I couldn’t see was where this text was ‘going’ when it started – it has a trajectory, but it’s invented through the writing. It’s never writing towards a particular (pre-destined) destination. It’s haunted by the future (the sense of moving forwards), but there’s no logical argument to follow. Its mode is perhaps more counteraction than fortification. It’s not trying to convince you of anything, except itself, and maybe not even that. There are no facts or secondary sources. (There are quotes and references, but as assailants, not reinforcements.) It doesn’t contain information. It doesn’t assume a single ‘position’. It switches address, it obfuscates, it suggests sub-plots. It uses strategies of interference, stand-ins and representations. It detours, it interjects, it miscommunicates. It attempts accumulation. It not only applies words but also is words – it (half-)knows its limits.

Could we talk for a bit about the book’s fixation with trousers…?

HP: The negative space of trousers, especially – two legs, two bum-cheeks, and a crotch. But, really it’s more of a fixation on clothes – in all their stylish, social, historic, economic, technological, sweat-shopped, self-conscious, sexual and fabric significance. We could probably do a whole interview on this subject but, perhaps, for now, we could just highlight a fascination with ‘what’s on the other side?’

The general definition I often hear of Art Writing is ‘experimental’ writing, with ‘experimental’ being something of a misnomer – it was Wallace Stevens who said: ‘all poetry is experimental poetry’. How do you define the term?

HP: I try not to. But yes, art is always (or should be) trial-and-error-ing, isn’t it? So I’ll second Wally’s motion, as with most things.

Near the end of the book you say ‘Art never seems to make us peaceful or pure. It swamps us in the jitters’ – Can the same be said of writing? Do you think the impetus is still for ‘peace’ and ‘purity’ even though we fail? (Your use of ‘jitters’ here is super – what I find most compelling about your writing is the way it doesn’t seem to want to sit still.)

HP: ‘Jitters’ is a high-yield word, isn’t it? So jittery.

When I use the term ‘art’ here, it’s not really limited to visual art, but more to that crisis of cause and effect I mentioned earlier – what’s detonated by this situation and how do I respond to it? (perhaps I don’t have a choice?) Speaking about Dostoyevsky’s characters, Deleuze described them as being generally agitated – a character is running, gets distracted, forgets, is perpetually taken by urgency. The character is overtly preoccupied by life and death but, at the same time, knows there is something even more urgent. And this is the expression of The Idiot – he knows there’s a problem but doesn’t know what it is. Alongside this insight, I’d like to add the artist Sturtevant’s assertion that ‘thinking is a kind of madness’. For me, there’s some kind of an answer in both of these examples. Personally, I never go to art to feel peaceful. Even (especially) the most ‘peaceful’ of music puts me in crisis – the jitters.

The artist Ed Atkins is the first acknowledgement in both of your books – could you talk a bit about your collaborative work?

HP: The answer to this is very simple. Ed is also an artist who writes – extraordinarily. We met a few years ago and became close friends very quickly. Sometimes (usually the best times), it happens like that. I got lucky. We share stuff – emails, conversations, books, meals, nights out, cinema recommendations, scepticism, wisecracks, apprehensions, lines of poems, drafts of videos and texts. We think in the same arena, but differently – this is useful. I loved working with Ed on the cover for Instant-flex 718 – I look at it and see our aesthetics intermixed. Also, A is for Atkins so he has that primary acknowledgment advantage.

Tom McCarthy claimed that the art world is more ‘literate’ than the literary world. He said ‘there’s definitely a more intelligent set of conversations around culture and around literature going on in the art world. In the art world people look outwards’. You navigate both ‘worlds’, and it seems to me that this book challenges a statement like McCarthy’s because it is a bridge between the two… Do you think that ‘world’ distinctions such as his are (still) relevant?

HP: Broadly speaking, art and literature do participate in different economies and, therefore, in those economies’ attendant languages. But, moreover, art has always been looking to redefine or expand its body-shape. Its modus is omnivorous. Its modus is interrogation. Literature, on the other hand, has perhaps been more concerned with maintaining its physique, with slimming down – and maybe for good reason given the ubiquity and co-option of language and the ends to which it’s deployed. How does literature identify itself contra small-talk, journalism, political rhetoric, bad jokes, a letter to my grandmother, all the crap spoken (usually by the most powerful) daily? But I do think it’s shifting, and rapidly – maybe literature doesn’t want to be in opposition to those things right now, or ever again. At least, in poetry, not so clearly – it might prefer to step all over them. And then there’s the issue of distribution – the internet crevices and trails in which new (‘unendorsed’) forms take shape and borders become flexi-permeable. Artists have been asking ‘what is art?’ for the last century or more, but it feels as if the question of ‘what is literature?’ has a new urgency. Certainly, the conversations I have with poetry friends and with their text-works are not so different from those I have with artist friends and with their artworks – we’re all just trying to articulate/make inarticulate with our available resources.

Heather’s current show, through the flesh-tone scenario, the imported combi-boudoir, is exhibiting at the Zabludowicz Collection, London until 3 November 2013. In 2014, she will have solo shows at Bunker 259 (New York), Grundy Art Gallery and Dundee Contemporary Arts