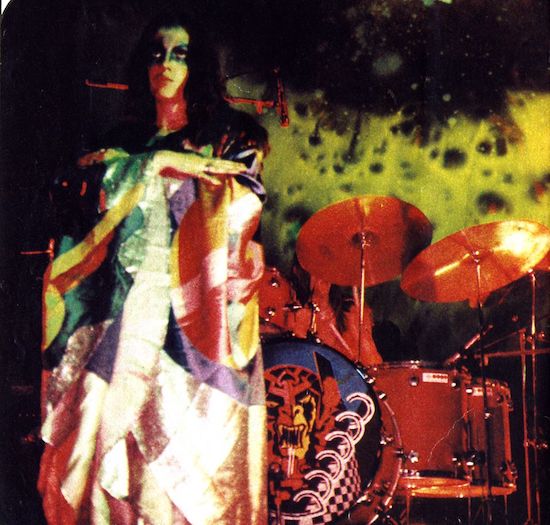

Live 1973 – from the Japanese single of ‘Urban Guerilla’

When I was ten or so, I discovered my older brother’s copy of the NME Encyclopaedia of Rock, published in pre-punk 1976. Partly, I suppose, because I looked up to my brother so much, I read it religiously and swallowed its opinions wholesale. It wasn’t complimentary about Hawkwind: “One critic has described a typical Hawkwind set as ‘four hours of 4/4 with the occasional trot in 8/8’,” it sneered. “Others have suggested the band is long overdue to add a fourth chord to the three they already know.”

In fact, it’s hard to emphasise enough how much of an outsider band Hawkwind were, even in their heyday in the 1970s. Founded in Ladbroke Grove in the last gasp of the previous decade, they were routinely dismissed as hippy recidivists, a poor man’s Pink Floyd, riding on the rapidly disintegrating tailcoats of psychedelia and the counterculture.

There was some truth in this, as there is in all myths. They were enthusiastic consumers of – and proselytisers for, acid – long after everyone else had moved onto cocaine and other more sophisticated thrills. Their performances were that most passé of things: a multi-media experience. Aside from the music, characterised by extended jams played out in cavernous, anonymising darkness, audiences also got a lightshow, dancers – sometimes naked – and spoken word readings. And yet, as Joe Banks argues in this detailed and compelling study of the band’s first and most important decade, to conceive of Hawkwind in those terms alone is to completely misunderstand – and under-estimate – both what they were doing and how significant it was.

From the beginning – their first, eponymous album came out in 1970 – Hawkwind did things differently. There are a couple of traditional songs on that album. Guitarist and principal songwriter Dave Brock (today the only founder member still with the band), was previously a busker – and it shows. But mostly they traded in atmospherics: simple rhythms, riffs and phrases which gained power through repetition underlying the squalling, treated saxophone of free-jazz fan Nik Turner and, more importantly, the electronics of DikMik.

Whereas other bands used the emerging synthesiser technology as just another keyboard instrument, DikMik used an audio generator – at the time used by no other band in the world aside from New York’s Silver Apples – to create whole species of pure noise. Buffeting, whining and roaring on top of the pounding rhythms, it sounds like nothing so much as a pagan god of electricity thinking out loud to itself.

Robert Calvert – Atomhenage 1976 tour

The band were marketed as ‘space rock’, a queasy nod to their debt to the likes of Pink Floyd and, to a lesser extent, Soft Machine. But really their primary influence was the Velvet Underground of ‘Sister Ray’ – although, as Banks points out in an excellent overview, other precursors included San Francisco band Fifty Foot Hose, Delia Derbyshire, and the 13th Floor Elevators. In this, as in other things, Hawkwind have much more in common with German contemporaries Can and Neu! than they do with their British peers. Bowie aside, no-one was much influenced by the Velvets in Britain in 1970.

Certainly, Hawkwind’s antipathy to traditional song structure is wholly opposed to the structural experimentation of their prog-rock peers. Whereas those bands extended their compositions by splicing together different time signatures, tempos and keys, Hawkwind were brutally minimalist. Often their records did away with needless complexities such as choruses – never mind pre-choruses or bridges – because the kinds of dynamics inherent in those formal elements were inimical to the music they made. In this respect, as Mute’s Daniel Miller notes here, tracks like the fiteen-minute long ‘You Shouldn’t Do That’ on their second album – which for most of its length is just two chords played in such a rudimentary pattern it’s a stretch to even call it a riff – share more structural DNA with the acid house or trance of two decades later than anything else.

But for all that you can hear where some of the band’s sonic palette comes from in the late-sixties underground, Banks is surely right that Hawkwind’s “psychedelic visions… predated the UFO club… [and] reached back into a pre-history of ritual and ceremony”. The music was self-consciously shamanic: the point was always to dissolve the ego using repetitive rhythms and riffs, vocal chants and sheer volume – not to mention strobe lights directed at the audience and other visually disorienting effects. “You can force people to go into trances,” Brock said at the time. “It’s mass hypnotism.”

DikMik’s audio generator also affected people both physically and mentally: if the frequencies went too high, it disturbed the inner ear. People collapsed and sometimes vomited. With very low frequencies, on the other hand, people could lose control of their muscles – with all that implies for the lower digestive tract. “We were a black fucking nightmare,” Lemmy, who joined in 1972, has said. “We used to lock the doors so people couldn’t get out.”

Hawklords tour 1978

The band themselves were not immune to the psychological assault their music represented. “We were playing a heavy riff for about four hours with strobe lighting going on and off, and it freaked me out so badly I just had to get away,” Brock said of an early free festival. “I gave my guitar to the nearest person… and just walked up to the top of the hill, but I still couldn’t get rid of this thing in my head.”

In shamanic cultures, the rituals and ceremonies are ultimately about transformation – the ability of the shaman actually to become another being, to be possessed by another spirit. For Banks, this is a key aspect of what he calls Hawkwind’s radical escapism: they offered not just a counter-culture but a counter-reality to a paranoid and profoundly disillusioned decade. Reality you can rely on, to use one of their slogans from later in the decade. As the country lurched deeper and deeper into crisis – be it political, economic or environmental – and trust in authority bled away, the band’s millenarian rejectionism of corporate and societal norms seemed a positive model for action.

It’s worth pointing out that Hawkwind’s outsider status – their determination to work outside the existing norms – wasn’t passive. At a time when the authorities were clamping down on the counterculture, Hawkwind were busy exporting it from London to the provinces, distributing free drugs, contraceptives and copies of the underground press – Frendz and International Times – at their shows. They played endless free gigs for any cause that asked them – from miners on strike and Greenpeace to would-be revolutionary terrorists, the Angry Brigade – and often for no cause at all other than the symbolism of free music. When police attacked the Peace Convoy at the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985, the travellers were on their way to the Stonehenge Free Festival, where Hawkwind were practically the house band. Hawkwind themselves were regularly investigated by the police – some sixty-eight times in the first few years alone; roadblocks and searches were common. (It turned out that one of the advantages of DikMik’s skill on the audio generator was that he could disorientate sniffer dogs with frequencies the human ear couldn’t hear.)

Banks doesn’t quite put it as baldly as this, but essentially he argues that Hawkwind quickly became a cult in both senses of the word, with their audience experiencing the music as a quasi-spiritual phenomenon. But, like all cults, they needed a mythology. Theirs would be discovered in deep space.

Atomhenge 1976 tour

Key to this transformation was the arrival in the band’s circle of poet Robert Calvert in 1971. He took the concept of space rock and realised its metaphor, folding it around the idea of psychic rebirth the band sought to enact in their shows. Now Hawkwind was a spaceship, its members the crew. The trance state became, metaphorically, ‘techno-sleep’, the long, suspended animation of travel into deep space; the further you travelled into the void, the deeper your understanding of yourself; the performance was a journey, an arrival in a future of your making. As for the dissolution of the ego, it was no longer just shamanic: now it was also a philosophical acceptance of what fellow countercultural activist Mick Farren, with reference to their live shows, called “the horror and sadness of the tiny human juxtapositioned against the infinite universe”.

These ideas find their most articulate expression in the Hawklog, a twenty-four-page booklet which came with the band’s second album In Search of Space, compiled by Calvert in partnership with the the band’s hugely influential designer Barney Bubbles. Bubbles began working with them around the same time as Calvert and gave them a startlingly incisive and compelling iconography, a visual language that drew on, among other things, Egyptology, golden-age science fiction and fin de siècle Art Nouveau. Between them they fleshed out the conceit of band as deep-space travellers in what is an extraordinary extended exercise in Burroughsian cut-up, fizzing with intellectual energy, alternative belief systems, and a thoroughgoing disrespect for copyright law.

On one level, of course, it’s easy to view the over-arching conceit as no more than risible narcissism. But Calvert, I think, was aware of that and embraced it, bringing to it a theatrical sensibility and a profound sense that the search for any meanings beyond your own self, your inner space, was always ridiculous. You never quite know where the irony ends and the seriousness begins. The idea itself has a kind of ‘pataphysical absurdism: under Calvert’s direction, Hawkwind took a pulp aesthetic and pursued it with such single-mindedness that it became imbued with real meaning. He brought the existentialism to what Banks calls the band’s “existential protest music”. They now aimed, Calvert said, to “hypnotise the audience into exploring their own space”.

As Banks makes clear, what Hawkwind are doing here is, among other things, reconciling science fictions two opposing tendencies: on the one hand, the exploration of outer space in pulpy heroic fantasies of discovery and conquest; on the other, the exploration of dislocated identities and fractured psychological states of 1960s speculative fiction, as practised by the likes of Michael Moorcock – a long-time Hawkwind associate – JG Ballard and Philip K Dick. It’s an under-regarded achievement; but then, as Moorcock suggests here, science fiction and rock ’n’ roll might be the two most despised art forms of the 20th century.

This period of the band’s work reached its apotheosis in their winter 1972 Space Ritual tour – financed by the surprise success of million-selling single ‘Silver Machine’, co-written by Calvert – earlier that year. The live recordings of that tour, released in 1973 as Space Ritual Alive, is certainly the place to start if you want to understand Banks’ thesis about the shamanic power of the band in full flight. Over ninety-odd minutes of uninterrupted music interspersed with dystopian, occasionally psychotic, spoken word pieces – delivered by Calvert with patrician hauteur and terrifying conviction – it builds from crescendo to crescendo until, with the final track ‘Master of the Universe’, the music explodes with such juddering, frantic power the band are playing so fast they can hardly keep up with each other.

HAWKWIND from Qui Giovani magazine july 1973

It’s certainly the album that got me interested in the band, and one of its signature charms is that, while it’s recognisably music, the only instruments that consistently sound like themselves are the relentless hammering of Simon King’s drums and Lemmy’s thunderous bass. Although if I said that Lemmy also provides the most reliably melodic element in the mix it gives you some idea of what to expect from everyone else, whose playing is ferociously distorted, transmuted into layer after layer of electronic sound and fury. Brock’s elemental riffs are, of course, at the genetic core of their sound, at once so modern they might have been brutalist architecture rendered in blocks of sound and yet so gorgeously, shockingly primitive he could have dug them out of a meteor crater in the Yucatan or chiselled them off the cave walls at Lascaux. Turner’s sax, meanwhile, honks and squawks through it all like a flock of interstellar geese angrily learning how to play Ornette Coleman. It’s the most exhilaratingly nihilistic thing I know.

The band would never quite manage to sustain the same intensity again. Saying no to societal and cultural power structures is exhausting, and it’s clear how debilitating the struggle became for Hawkwind in the mid-1970s. DikMik and Calvert both left in 1973 and I’m not sure that, on Banks’ account, the pressure to compromise and conventionalise wasn’t ultimately responsible for the divisions that fractured the band over the next couple of years. Lemmy and Turner would both be sacked – along with a couple of other band members – and the band also parted ways with iconic dancer Stacia, who had always been a vital part of their identity as a live act.

Arguably Hawkwind lost some of their conceptual focus in this period too. It’s true 1975’s Warrior on the Edge of Time – a fan favourite – does have a concept. But while its sword-and-sworcery theme, loosely based on Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion series, might be escapist, its radicalism is harder to perceive. At least, I wasn’t entirely persuaded by Banks’ attempt to fit it into his wider narrative.

Levitation 1980 tour

Calvert rejoined the band in 1976 and the three albums-worth of material they recorded in 1977–8 – Quark, Strangeness and Charm, 25 Years On (released under the Hawklords name) and PXR5 – are among the best and most consistent they made. It’s the only period for which Calvert wrote almost all the lyrics, and his conceptual concerns, at once both future-facing and urgently contemporary, are more lucid and direct than any of the band’s other songwriters. While the ritual space chants are long gone, and the music is more structured and conventional, the radicalism – the offer of an alternative, rejectionist understanding of reality – is still very much there. In particular, the dark satire of Pan Transcendental Industries – developed by Calvert, again in partnership with Barney Bubbles, for the 1978 Hawklords tour, and drawing on the thinking of architectural theorist Rem Koolhaas – offers a prescient metaphorical critique of global corporate hegemony that’s acutely alive to the essential absurdity of hegemonic ambition. The tour programme came in the form of a corporate brochure for PTI, a business engaged in the industrialisation of religion; proof of PTI’s success, Calvert writes, is the fact that angels have now exchanged their wings for car doors.

By 1979, Calvert had left the band again – for the last time – and while Banks goes on to discuss Hawkwind’s tour at the end of that year and their 1980 album Levitation, I’m not sure he shouldn’t have ended his book with the last of Calvert’s work to be released. Decades are an imprecise measure of anything and Hawkwind’s 1980s – a difficult and very different period for the band – began with Calvert’s departure.

However, that’s a small criticism of what is otherwise a tour de force. Banks has tried to do a great many things in Days of the Underground, and he has succeeded triumphantly. He is, of course, making the case for Hawkwind’s musical and cultural radicalism. But he is also arguing in favour of countercultural mores, an anti-authoritarian, millenarian rejectionism that overlaps with mainstream radical politics in its contempt for contemporary power structures but breaks decisively against the conventional revolutionary ideas of the Marxist tradition. More generally, he is also asserting the importance of both rock music and science fiction as cultural forms.

The book has an unusual structure, with chapters dedicated to chronology, track-by-track album analyses and interviews interlaced with lengthy essays. I suspect there will be new details for even the most obsessive of fans. I didn’t know, for example, that Michael Nyman nearly joined the band at one point, and the thought that Calvert and Brock once contemplated a musical based on Dan Dare is certainly something to chew on. But the book stands or falls by the quality of the essays, and these are uniformly provocative and insightful exercises in cultural history with important things to say about Britain in the 1970s. Among other things, it complements nicely Paul Gorman’s wonderful 2010 study of Barney Bubbles, Reasons to be Cheerful – although we still need a serious work on Calvert, whose career both with and without Hawkwind continues to be neglected.

Some might argue, I think, that there has never been anything radical about escapism – whether based on psychedelics, space-age fantasy or relentless, hypnotic rhythms. Isn’t all escapism ultimately reactionary, the argument goes, a refusal to treat with the politics and conflicts of the moment? The counter to that, I think, is Hawkwind’s vast influence on the musical culture. “Punk rock started,” Stephen Morris of Joy Division/New Order told The Quietus, “because in every small town there was somebody who liked Hawkwind”, and Banks has spoken to an impressive list of musicians who attest to that fact, among them Colin Newman of Wire, Richard H Kirk of Cabaret Voltaire and Jah Wobble of Public Image Ltd. A non-exhaustive list of other punk and post-punk artists inspired by Hawkwind might include Pete Shelley, John Lydon, Killing Joke, Dead Kennedys, Mudhoney, Pere Ubu, Primal Scream, and Julian Cope. Ten years later, dance acts like KLF, Underworld, The Orb, the Chemical Brothers and Leftfield also queued up to pay homage.

Not bad for a band memorably described in one early Melody Maker headline as ‘The Joke Band That Made It’.

Hawkwind: Days of the Underground by Joe Banks is published by Strange Attractor