It’s difficult to get a defining sense of Ai Weiwei, even as he becomes the most famous Chinese face since Warhol’s pop-art portraits of Chairman Mao. His story has been taken up in so many ways that the books, both by Weiwei and about him, stack up alongside the news editorials which buttress his own effusive stream of photos, tweets and blogs. Alison Klayman’s 2012 film Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry documented his rise as artist and activist, befitting a man who appeared on the cover of Dazed & Confused’s Human Rights Issue before guest-editing the New Statesman a year later. But rather than offer another angled spotlight on one of Weiwei’s many dimensions, Barnaby Martin’s Hanging Man captures more by widening the frame.

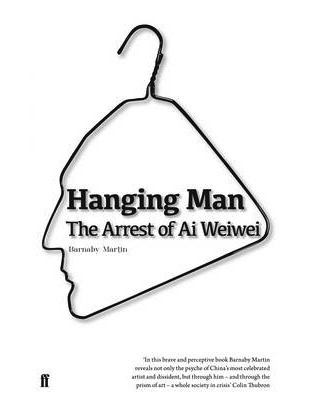

Martin has written a pacey, root-level account of post-Imperial Chinese history and contemporary art, a book about modern China ‘using an account of Ai Weiwei’s life as its backbone.’ Martin illuminates the early pieces and major exhibitions, from the modest coat-hanger profile of Marcel Duchamp (from which the book takes its name) to the iconic Sunflower Seeds and Zodiac sculptures which appeared internationally before Weiwei’s arrest and 81-day detention.

By travelling to Weiwei’s Beijing studio and home, where a government-controlled security camera is trained squarely on the doorbell, to conduct the most in-depth interviews since his release, Martin creates a convincing case for China as a place that’s changing for the better. This isn’t to make Weiwei a show-pony for progression (the ridiculous idea that if China wasn’t changing Weiwei wouldn’t be allowed to exist at all) but rather to show that the resilient first generation of post-Mao artists have contributed to an imaginative thaw in a country where the perception of reality has been frozen by the Chinese Communist Party’s horrific ideological grip.

The sinister thing is that he was never beaten. Although he sustained a head wound at the hands of the police in 2009, in detainment the torture was psychological and prohibitive. Such was the denial of information, contact, exercise and communication that he’s reported as saying ‘I really wished someone could beat me. Because at least that’s human contact’. Unlike the tens of thousands of disappeared who were killed in detention, or purged or banished, Ai Weiwei now lives with a precarious kind of granted liberty, darkened by the damoclean threat of re-arrest and violence. In seeking the interviews Martin had justified reservations. Would Weiwei be broken? Unable to speak freely and truly account for his time? At the end of Never Sorry, mentioned here as a ‘deft film’, we see the artist unceremoniously dumped on his doorstep holding his buttonless trousers together. ‘I can’t talk about it,’ he tells a waiting group of media hopefuls. He refused press more than 100 times, rejecting the BBC, CNN and 60 minutes. ‘Really I can’t. I cannot. I would lose my freedom again.’

Martin scoured his Beijing contacts in failed bids to reach Weiwei. He gave it one last shot. ‘I picked up the phone and rang his old mobile number. I assumed that the police would have confiscated it or turned it off, but to my surprise Weiwei answered.’

The fluid, conversational interviews find Weiwei without some of the pluck and glee that characterised appearances before his arrest, but he speaks plainly of his detention, embodying the transparency he works to force from the Chinese state. The man is ungovernable, matter-of-factly detailing the moment a black hood was placed over his head in Beijing, and the comic ironies of being interrogated by captors who seem torn over their roles as inquisitors. They know Weiwei is not a murderer or thief. They try to fathom his position, giving an amusing picture of Weiwei lecturing on art history from the confines of an interrogation room. ‘OK! We found out!’ say his captors. ‘You’re part of Dada.’ Well, says Weiwei, close… but not quite.

The ordeal actually fuels Weiwei’s hope for his stated ambition to change China: his response chimes with other accounts of politically-motivated detention – Brian Keenan’s An Evil Cradling, or Guantanamo detainee Murat Kurnaz’ Five Years of My Life. Weiwei sees humanity in his captors, often nineteen-year-old farm boys given a uniform and inculcated by ideology; he notes the significance of a jailer unable or unwilling to whack the handcuffs on with full force. These details allow Martin to zoom out. ‘People like Ai Weiwei can become like counters in a board game,’ he writes. ‘Their liberty or their lack of it, their status as a free citizen, is a by-product of the power struggles and horse-trading that take place far above their heads. They become a weather vane for the direction a regime is moving in.’

To this end Martin explores China’s dynastic and feudal history, the development of the CCP, and key episodes like the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square protests. He locates additional subjects amidst the urban sprawl and rural poor. He is followed as he seeks out the writer Liao Yiwu – author of Corpse Walker, a book of interviews with everyday Chinese people – and the poet Mang Ke, both of whom have been persecuted for pursuing free expression. Both help to convey the scale of Mao’s influence, making real the idea of a society where to have knowledge was to be punished.

But it’s by digging in to the history of Weiwei’s father, the once-revered poet Ai Qing, that Martin succeeds in illuminating the roots of China’s current identity crisis and Ai Weiwei’s exceptional circumstances. By looking at both father and son Martin creates a timeline of more than 100 years, showing how Qing once had Chairman Mao’s confidence, appointed to oversee cultural affairs from within the tightest circles of power. However he suffered by ‘getting too close to the sun king’ and was branded a triple criminal. In 1957 – the year Weiwei was born – the intellectual purges began; in 1958 Qing was banished to Xinjiang and then, along with his wife and young son, to a hole in the ground on the edge of the Gobi desert. Weiwei’s life began as a kind of imprisonment without arrest. His salad days in New York – working menial jobs, discovering Duchamp and studying under the unforgiving Irish painter Sean Scully – were a cakewalk by comparison.

While the wave of international protests in the wake of Weiwei’s arrest almost made him a martyr, his release transformed him into a symbol of endurance and hope. Martin may not always succeed in illustrating precisely how China is ‘diverse in its diversity’, but the mix of interviews, historical commentary and personal reflections make for a show-stopping dispatch more akin to Paul Mason’s Why It’s Kicking Off Everywhere than Hans Ulrich Obrist’s reverent-by-comparison Ai Weiwei Speaks. Much more than a portrait of the artist, Hanging Man shows that in the most populous and dictatorial country in the world the most committed citizens, activists and artists can turn even tyranny their advantage.

Hanging Man: The Arrest of Ai Weiwei is available now, published by Faber & Faber

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more