At the start of the recording of this phone interview with Grace Jones, while I’m waiting for someone to pick up the receiver, I appear to be breathing really heavily, like someone who is awaiting a very stressful experience. I sound like an astronaut waiting for blast off or a bomb detonation expert who is about to sever the blue wire with a pair of nail cutters.

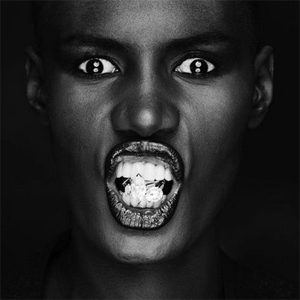

This is perhaps not unsurprising if you look at the popular

perception of Grace Jones. She is often seen as a difficult interviewee, probably because of her 1981 extraordinary outburst on The Russell Harty Show when she rained down blows on the hapless talk show host. To me this has always said more about how shit television was in the eighties than anything else. Who thought it was a good idea to have two guests and a chat show host all sitting in a row, necessitating Harty to turn his back on Jones who responded in a very physical and demonstrative manner? Perhaps she still retains an aura of the ‘man eater’ that would worry some. One of the more colourful stories that has attached itself to her is the idea that she

and Dolph Lundgren used to attack each other with baseball bats as part of their pre-sex rituals. However, this has no bearing on my laboured breathing. Really, it’s purely because she’s an artist of such standing that I’m bricking it. I probably haven’t been this afraid since I interviewed Mark E. Smith.

Now, this attitude will either elicit nods of recognition or howls of derision. She was treated with great mistrust by many in punk circles; seen as a dilettante. The anyone-can-do-it, DIY attitude applied to men with guitars! Not to women! Certainly not to black supermodels! It was as if the sublime deterritorialisation of punk, as predicted by Gilles Deleuze and

Fêlix Guattari in their book Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, only lasted for a few years or even just a few months before attitudes were reterritorialised into new lumpen and boring orthodoxies of what was real and acceptable. How quickly they forgot that they were the ones being lambasted by rock critics and prog rock bores just months beforehand for not

being ‘proper’ musicians. Some (but by no means all) punks saw her as the enemy because she was fake and pop. But sonically, her experiments with disco were more radical than Gang of Four’s, and her experiments with reggae much more satisfying than those of the Clash.

It was perhaps natural that Grace would grow up an outsider. She was born at some point about six decades ago in Spanish Town, Jamaica into a deeply religious and conservative family (no one seems to know her exact birthday). The immediate family moved to Syracuse, upstate New York when she was a teen and she eventually ran away from home to study drama. Perhaps not unreasonably, she came to the conclusion that her look and accent were too strong for the US, so she moved to Paris where she became a successful model, appearing on the cover of Vogue. In 1977, the far-sighted fashion guru Issey Miyake persuaded her that she should combine two of her passions — music and fashion — and this led to a record deal with Island. After some decent enough pop fare that included the singles ‘La Vie En Rose’ and ‘I Need A Man’, she began to realise her true potential when she became embroiled in the New York City disco scene, combining threads of reggae, disco, post punk and synth pop into a sublime whole on the albums Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing. She released notable collaborations with both Trevor Horn and Nile Rogers in the eighties, but after a long and baffling absence from major musical projects she has recently seen an undisputed return to form in the shape of her new album Hurricane, which sees her team up with trusted old allies (Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare) and some new ones (Brian Eno).

The phone keeps on ringing and outside the window the full moon is massive and bright. After an aeon of heavy breathing, a button is pushed and a rich, female accent that is simultaneously French, Jamaican, American and English

says: “…I just hope he’s intelligent, that’s all I have to say. Whoops! Did you hear me?”

“No,” I lie.

“Good!” she roars [not for the last time].

How are you?

Grace Jones: I am lovely. As well as can be expected when the full moon is coming out.

It’s my pleasure to talk to you on the eve of the release of your new album, Hurricane. Why haven’t we heard from you musically for so long?

GJ: How long are you talking about?

Well, I know you had a single out but I’m talking albums. And you haven’t had an album out for 19 years by my count.

GJ: Ah, I see. Album-wise it has been a while. Music-wise it has always been there.

You’ve been doing musicals and singing on stage as well as the singles, but what prompted you to record a new album?

GJ: It was an accident, actually. Excuse me, I have a lot of movers in my flat at the moment and I’m trying to find somewhere where we can talk quietly. I’m in my new flat in London and I’m having my furniture moved out of storage. Okay, hello John! Actually, it wasn’t really an accident. Ivor Guest [producer and on/off boyfriend] was searching for me because he wanted to add my voice to a project that he was doing called Biomechanics. He had a wonderful track and I’m always writing lyrics and not thinking whether or not the melody is going to follow, but the melody did fit perfectly with the track and that’s how it started; that was the jump start. You must

forgive me, I was up until seven this morning editing photos with Chris Cunningham. He is involved in a visual way and also experimenting with his visuals in a musical way. Do you like Chris Cunningham?

I like his stuff a lot.

GJ: Well, we’ve been working together and I’m just a bit hmmpfff, hmmpff… exhausted! But in a very good way! I’m just making excuses in case I sound a bit… euphoric!

You’ve always been a night person, haven’t you?

GJ: Morning and night actually. I love both extremes. I like working until the morning, so I can see the day and then I like to go to sleep and then get up before sunset. But I love the energy of the morning.

What was it like hooking up with Sly and Robbie again?

GJ: It was as if we’d never been apart. It could be something to do with space between albums as well; I just wanted to work with them again. I did start doing an album with them before — about three tracks — but I didn’t get them together playing organically, and I didn’t like the outcome of it. And that was one of the reasons why I never released what we did. Some of

the songs were already there — one third, let’s say — and then this time it really flowed well. It flowed like a river. It really felt right, especially on the track ‘Devil In My Life’. The more you listen to it, the deeper it will take you. It has the big symphonic sound which we got at Abbey Road with a big orchestra, which was amazing.

It’s quite striking how modern the album sounds, but there’s also a direct sonic link to Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing.

GJ: That was the purpose. It was a conscious decision to have stuff from the classics… They have become classics apparently, and I’m just finding that out myself. They have a timeless sound and I love that, really; I love the way they sound, and Ivor who produced the record absolutely loved those

records as well. So it seemed like both of our ideas came together at the same time. It was supposed to sound modern and, at the same time, have no time. Sly and Robbie: their sounds have no time. When we work together we make up a sound that will always be new.

It’s certainly the case that a lot of bands are influenced by you and the period that spawned you; that of post punk. Many bands look up to Joy Division, Tom Tom Club, Wire… But does this go both ways? Do you keep up with modern music?

GJ: I do and I don’t. I keep up with music. Sometimes some friends will play me Captain Beefheart and then I will listen to some modern stuff. For me, though, I think that Captain Beefheart will always be modern. And Tom Waits will always be modern. He makes a poetry that will always be married to melodies that are unique. This combination for me is always modern. I guess I’m trying to say that trends — when you have one hit and then everyone wants to sound like that one hit, and people tend to do that, going, ‘Oh, this is a hit so let’s make everything for the next 10 years sound like that’ — drive me totally mad.

The trouble with the major labels now is that as soon as something becomes fashionable, they jump on it with all the money instead of allowing artists to develop.

GJ: I’m happy that you see that. Not many people see that. But it’s happening in many ways, and not just in record companies. This sort of thing happens in everything — politics, for example. I guess I’m just totally anti-the-whole-system that you have to get caught up into. You end up with no

choice left to you anymore.

Do you think it’s harder to be a creative person in 2008 than it was in 1978?

GJ: No, never. It’s not harder. One just has to do it. That is all. Whatever one is creating, one has to stick to one’s guns and just do it. That is all. Put your foot down and do not let your work be compromised.

You’ve studied theatre and been in films and, according to an interview I was reading recently, you were a self-confessed art groupie…

GJ: That’s a song actually. ‘Art Groupie’ off Warm Leatherette [it’s actually off Nightclubbing]. That is one of my favourites.

I know the song. I suppose what I’m driving at is that in every aspect of your life you appear to be creative, whether it is music, fashion, or art. Is this a compulsion?

GJ: I think it is just me. It is me. It is not 100 per cent me, but it’s definitely in my dreams and imagination. It is a big part of me. My dreams and imagination.

With Hurricane, it seems to me to be a very sensual record; very grounded in the physical. Even if you just look at the titles: ‘William’s Blood’, ‘I’m Crying’, ‘Sunset Sunrise’…

GJ: Of course it’s sensual. All emotions are sensual. It goes from one extreme to another. They are all sensual emotions. Even if I sing like a robot, it is still an emotional robot. Do you know what I mean?

I do and I think there is a certain way of singing that I think you and certain other artists used that may have ostensibly been judged as slightly robotic but was essentially very soulful.

GJ: Well, it’s got to come from the soul. Where else is it going to come from? Some songs come from my head, some from my throat, but there will always be moments when it is an injection of the soul.

Tell us about your childhood in Jamaica. What were you like as a school child?

GJ: Competitive. Sporty. I think religion played a big part of it. My granduncle ruled, in Pentecostal rules. He was the Bishop of Jamaica. I think that is already out there somewhere! I’m telling you this so you will get a feeling for how this affected me. Because of this, I was very sporty and competitive. It was also a combination of having three brothers and a sister who lived round the corner. My step-grandfather was an elder in the church of my grandmother’s brother, with my granduncle, who was the Bishop. So it was a lot of discipline. You have to know what you’re going to be from the age of eight, for example.

How did you see your life panning out when you were that age?

GJ: The plan was to be baptised and receive the Holy Ghost and go to study as a school teacher. And somewhere in this plan there were languages as well. I wanted to teach many different languages, so that meant lots of travel. Books? Okay. But travel was better for learning languages. That’s what I dreamt of. When I was young I would see a jungle — not a real jungle

but some trees when I was going to the shop to get milk — and in those trees I would see lions and tigers and bears. And I guess this had a lot to do with the fantasies of travel that I had when I was a child.

Did you suffer culture shock when you moved to Syracuse?

GJ: Absolutely! But in the best way. I had never seen snow before! And I’m still shocked every time I see snow. The first bit of snow each year… I stay up and I watch it. And then I go out and pick it up and eat it and move around in it. That is culture shock alright [starts howling with laughter].

Apart from the weather…

GJ: [whispering] I wish you were here.

I wish I was. It sounds like a good laugh.

GJ: [more laughter and squealing] It is.

What did people make of you?

GJ: Well, everyone thought I was brilliant. It was a technical thing [bursts into laughter]. Oh my God! Right, in Jamaica we had the English way of schooling from the age of four, so when I got to America I was already a few years advanced because I started school at the age of three-and-a-half rather than six and my grades moved up accordingly. In America, they start

you at school at six because the grades are different. I had to take a test and they didn’t know what to do with me. It wasn’t that I was any smarter; I had just started younger. All of a sudden I was jumped from eighth to tenth grade. They said I was very smart, but I was only smart in languages, really. Cooking was a disaster! But I am learning now. I have seven meals for each seven days of the week.

What is the best dish that you cook?

GJ: Carbonara. Arrabiata. Mmmmmm!

Nice and spicy.

GJ: Uh huhhhh. Breaded rack of lamb. Jamaican country chicken. Jamaican curry chicken. Oooh la la la! And grilled steaks or lamb chops, and that’s it.

When you moved to Syracuse, did you rebel against your family’s religion?

GJ: I left as quickly as I could. You can’t rebel more than that. I just disappeared. I went to do plays after leaving school. There were nine of us — The Ruskin Players — and we did Shakespeare and the classics. I did that for one year and then I didn’t come home. They knew where I was, but they didn’t know how to find me.

Right.

GJ: You don’t understand what I meant by that, do you?

Not entirely.

GJ: I sent them letters, of course. But the letters said I was upstairs when I was downstairs.

Ah.

GJ: It’s the bloody truth. I have no idea how you are going to write it! I’m sorry.

Don’t be, it’s interesting.

GJ: Well, you keep some of it for yourself. You promise?

I will do.

GJ: Good. We can do something later…

In some senses, you were quite rebellious then?

GJ: I was totally rebellious. That’s what I mean about disappearing. I changed my name. I became a go-go dancer. For theatrical reasons, of course. I was 15 or 16. I would be locked up now. Being 15 and doing that is illegal.

Do you think that people don’t know how to deal with wilful or autonomous teenage girls?

GJ: People? People in general? Are you talking about me being 15? I was like a runaway but I wasn’t a runaway — I was in the middle because I was working. After the work was done, you know, then I disappeared letting them know that I was okay. So there is a difference between that and completely disappearing and not letting anyone know where you are. I let them know I

was okay. And then I showed up on a motorcycle. Wearing hippy beads. On acid.

You were a hippy?

GJ: I was a wannabe hippy. I guess I still had the religion in me, but I got as close as I thought I could.

How did you get on with LSD?

GJ: I loved it. But I only took it for therapeutic reasons. I wouldn’t do it anymore because, you know, I had the best. I had it from the doctors.

The doctor prescribed it to you!?

GJ: No! The witch doctor!

Ah, I see. I was going to say…

GJ: Oh, do come on! It is different now. In that time, it was under someone who helped you through it if you were going to have a bad time, or talked you through in different directions. I didn’t know that, though. I just opened my mouth and swallowed. But I was lucky.

I do think it’s helpful to take it a few times when you’re younger. It can help you see different possibilities.

GJ: Yeah, but you can also kill yourself. Or you can learn. Again, I did it under very good supervision. And there is a time for everything. There is a time to take it and a time not to take it. You shouldn’t take it when you’re feeling bad. You have to take it when you are feeling good. And that applies to every drug.

When was the last time you took drugs?

GJ: I just had a joint while I was talking to you then.

Oh right! Was it nice?

GJ: Well, it’s heavy. I was having stress and I don’t like having prescription drugs. Arghhhh! That shouldn’t even come out of my mouth! I hate prescription drugs! They don’t tell you everything that is in them.

Speaking as a mother, what is your position on drugs when people ask you about them?

GJ: I always say, ‘Prescription drugs can be even worse than illegal drugs. The only difference is the legality.’ I’m running for president, what can I tell you! I’ve lived long enough to feel the sway of corporations both legal and illegal. Corporations give you drugs and they prescribe and prescribe them and they can be worse for you. Whereas you have illegal drugs and that is all about moderation. You have to know your body. It is like an allergy. Some people can have an allergy to feathers, so you don’t buy a pillow with feathers, right? But, at the same time, someone can cure their eyesight by smoking a little bit of marijuana. Who is to say which should be illegal: the pillow that you might be allergic to or the marijuana tea that might cure your eyesight? Who is making those decisions? The individual has to do it. You get a reaction immediately the first time you use it. If you have a cigarette for the first time, you cough and that means your body doesn’t like it. I smoke once in a while. The first cough I get I put it down. Cigarettes are legal though, right? They are the biggest motherfucking killers in the fucking world, right? I have a very good friend who can’t stop. They can stop heroin. They can stop coke. They can stop sex. But, hello! HELLO!? They can’t stop smoking. What does that tell you? Everything in moderation and know your own body. Keep on following the yellow brick road.

Talking of following roads, how did you come to move to France

GJ: That was for my modelling career and I just wanted to travel. I just wanted to travel. I knew that my Jamaican accent wasn’t going to get me any work so I went to Europe and hitchhiked from Luxembourg to Paris. I stood on the wrong side of the road! Somebody stopped and told me. I remember getting the train some of the way sitting on the floor of the carriage with these people playing guitars. That was when the record deal thing happened for the first time. I was with Issey Miyake, who was very important in my career. Because he introduced the modelling and singing together with my first record, ‘I Need A Man’. And I love him for that. That allowed me to… he saw something in me that I couldn’t see in myself. I was modelling to pay my rent, but he said I should combine the modelling and the singing. So I combine everything now!

What was your version of ‘Imagine’ like?

GJ: ‘Imagine’? You know what? I think it is recorded somewhere. But it was one of the songs… Wait! How do you know about that!? How do you know!?

Ah ha, I’ve been doing my research!

GJ: Oh God, you’re good. You are very good. I like that. Hmmmmm!

Ha ha! Well, I believe you did ‘Imagine’ and ‘Dirty Old Man’?

GJ: Yeah, but ‘Imagine’ was my absolute favourite. Shall I sing it for you?

Oh yeah, that would be great.

GJ: [sings ‘Imagine’.] I still love that song and maybe I will cover it again. But back then I sang it terribly. I was so nervous.

I believe you took singing lessons after that but you didn’t react very well to them.

GJ: Not the French one. My French singing teacher was like Hitler. Oh God, you are laughing. Are you German?

No, I’m from Liverpool. I just thought it was a funny description.

GJ: He was a fucking character. I thought you must have been from Germany.

No, I’m from Liverpool.

GJ: I love Liverpool! Now I definitely have to meet you. I’m lighting a cigarette. Please hold on Mr Liverpool. We have 15 minutes and then there is another call, but don’t worry, 15 minutes is a long time.

Er, it certainly is. What did you get from singing lessons?

GJ: I’ll give you an example, okay? I went to sing with Pavarotti, which was for me the height of my vocal achievement. Now, my attitude had always been, ‘Meh.’ Rock’n’roll mixed with a little bit of church; hit that note if you can and, if you can’t, rap it. But with Pavarotti I wanted to hit the highest highs with him. I went to Venice and I did a crash course in

operatics and the voice. After two weeks, I went out saying I couldn’t stand it anymore. I said tonight I’m going to drink spirits and smoke as many cigarettes as I can and go into my singing lesson tomorrow and see what has happened to my voice. I lost four notes on the scale of the piano, and that was when I learned about my voice. For some people, they can do that and it won’t affect them, but for me I lost the ability to hit those notes. I knew that affected me in a way that it doesn’t affect anyone else. The voice is a unique thing. Some people can get totally, totally high and sing the note on a dime, but my voice doesn’t do that.

When did you first become aware of disco music?

GJ: I was a dancing disco queen and disco was the best to dance to. It was an accumulation of the time and the sound system had a lot to do with it. It was very church, to be honest. My upbringing in the church had a lot to do with it. Disco was like the celebration of music through dance and my God! When you heard the music sometimes it was like, if you don’t get up and dance, you aren’t human!

It’s interesting that you have links to both ‘pure’ disco and the post punk/alternative strands of disco. Not many other artists do.

GJ: It is experience, dear. I experienced the best of disco in the late seventies. But that was only its name then. The name changes. Dance has always existed and disco really existed before that period and then after as well. Disco existed before we were all born and will exist afterwards. It is a ritual — it is a celebration — and it is the same kind of music that we call disco or rock’n’roll or a whole list of names that we can call it. Call it what you will, nothing will change the fact that certain kinds of music will make you want to celebrate or party. I love house! I love house music!

When you were younger, you had a reputation as a ‘wilful’ model who perhaps lost out on some jobs because you would just shave your own hair off. You certainly had a reputation as a model who wasn’t going to be pushed around. What do you think when you see lots and lots of younger models starving themselves down to a size zero?

GJ: Well, I certainly wasn’t going to play by the rules. Actually, I didn’t know there were any rules. When you start in that business the rules are imposed upon you, but when you stay in the business long enough the rules could be broken. A face could break the rules. Meaning: ‘You’ve got that face, we don’t care what your body looks like.’ They don’t do that anymore. It’s a power thing. It’s a control thing. The designers make the

samples of the clothes to fit that size zero, so when they call you in for a cattle call it’s going to be whoever fits this size is going to be the one who stands a chance of being picked. And I’ve got a problem with that. It’s corporate cannibal. I understand it, but I don’t like it. I understand it

because I had to be measured from head-to-toe, and to stand on tip-toes to get into the top model agencies. I did a little bit of cheating, but once I got in the door I broke the door down. I didn’t know I was breaking the door down until after I did it, and then they said, ‘You broke the bloody door down!’

Presumably you have another single coming off the album?

GJ: Yeah. ‘William’s Blood’.

How are we doing for time?

GJ: I don’t know, honey… I’m just here!

Well, I’m going to keep on asking questions until someone asks me to stop.

GJ: [roars laughing] Why don’t you come for dinner?

Why don’t I come for dinner? That’s a good question.

GJ: What do you like to eat?

Pasta.

GJ: Pasta. Oooh la la. Okay, I can do that.

Ah. Right. I’m all flustered now. My mind’s gone blank.

GJ: [purrs] Oh, don’t get all flustered.

Er, what’s it like working with Brian Eno?

GJ: Brian and I have always passed like ships in the night. I’ve known him for years but never really met him. That kind of thing.

You seem like an ideal pairing.

GJ: I know! We knew each other but never met each other. Well, I met him at a documentary screening and he wanted me to sing this gospel song for him and it just jumped into my head that we should work together. I asked him if he would want to work on the project and he said, ‘I don’t want to produce! I don’t want to produce! I just want to be one of the musicians and have

some fun.’ And I said, ‘That’s okay by me.’

You do have a knack for working with good people.

GJ: It’s not just a knack. They’re people that I meet on the yellow brick road.

Where do you think that the yellow brick road will take you in the next few years?

GJ: I don’t know what I’m going to be doing in two years or even in two weeks. I have to live for today.

Well, that’s a great answer and thank you very much for talking to me.

GJ: How do I meet you? I like you very much.

Miss Jones! You are naughty…

GJ: Well, it has nothing to do with naughty. I like your brain. I’m allowed to fuck your brain. Okay? I like your brain that is all and I think we should meet.

The very second I hang up, I’ll pass on all of my contact details to the PR woman.

GJ: No, give them to me. There are too many people sometimes.

Do you have a pen?

GJ: I have it here in my hand. It is red. I’m trying to write it on the bed but it keeps on sinking into the mattress. Hmmm mmmmm!

Oh, Miss Jones!

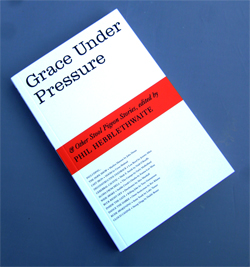

Grace Under Pressure is an anthology of articles from the first five years of Stool Pigeon. It contains articles on Marilyn Manson, DOOM, Lou Reed, The Fall, The Cramps, Killing Joke, Sonic Youth, Snoop Dogg and more. To order a a very reasonably priced copy click here.

And you’ll be pleased to know that Miss Grace Jones is performing live at the Royal Albert Hall Monday 26 April. Click here to buy tickets.