The internet, particularly since the advent of social media, has allowed us to create our own personalities. Suddenly, our identity is as malleable as playdough and, with a carefully-posed selfie and a few bon mots on Twitter, we can be anyone we want to be. We make ourselves wittier, prettier and more intelligent. We invent our own histories. And for those of us with darker thoughts, we can persecute those who we deem to have wronged us with impunity. If sticks and stones don’t hurt, surely electrons and pixels can’t? But that’s only the case up to a point and online abuse inevitably escapes from the confines of the browser window.

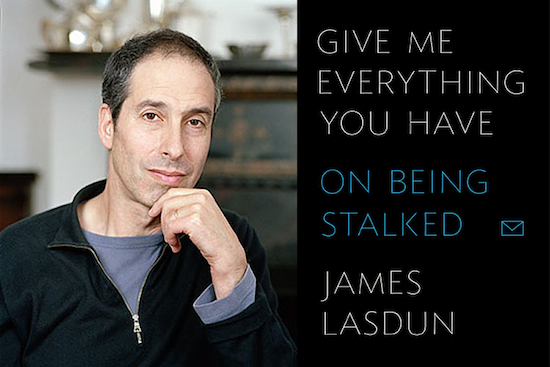

In 2003, well-respected British writer James Lasdun was teaching a graduate creative writing workshop at a New York college. One of his students was a woman he calls ‘Nasreen’, a talented young Iranian writer. Nasreen’s writing is full of ‘clear and vigorous language, with a distinct fiery expressiveness’ that makes it ‘a positive pleasure to read’. They form a healthy teacher-pupil relationship that concludes naturally when the workshop ends. Lasdun expects never to hear from her again, occasionally remembering the student with “a sunlit future of artistic and personal fulfilment”.

So when Nasreen contacts him two years later, asking him to read the completed draft of her novel, he is initially surprised but gradually falls into an amiable email correspondence. Her emails are chatty, exuberant and mildly flirtatious in tone and he – rather childishly – comes to see her as a ‘brand new friend’, an exotic specimen whose “otherness” gives her an appealing novelty.

“That she was younger than me, a woman and Iranian were all things that gave the prospect of this friendship a certain appealing novelty (most of my friends are middle-aged Western men like myself), but the main thing (given that any relationship between us was likely to be of a purely epistolary nature) was that she was a fellow writer whose work I genuinely admired and who seemed to enjoy being in communication with me. I assumed she felt something similar about me.”

Over time, Nasreen drops considerable hints that she desires their relationship develop into something more: she proposes that Lasdun smuggles her into his roomette when he tells her he’s intending to travel cross-country by rail; she calls him ‘sir’; she spins an innocent query on the veil in Muslim culture into a suggestive, sexually charged conversation. She is coquettish but also persistent, bombarding him with email after email – a barrage of psychic warfare designed to grind him down into gradual accepting her charms. Throughout all of this, Lasdun is at pains to point out that he is a married man and devoted father and there is a depressing inevitability to what happens when he finally rejects her advances. As if someone had flicked a switch, Nasreen changes from enraptured pupil to enraged woman. Her revenge is brutal and, we discover, unrelenting.

Lasdun is a writer of considerable skill, and what could easily have been a schlocky Fatal Attraction retread is instead filled with taut, slowly encroaching terror. Self-described “verbal terrorist” Nasreen comes across as more wraith than person, an unrelenting torrent of malevolence. Her emails to him comprise accusations of sexual abuse, homophobic slurs and bilious anti-semitic screeds. ‘You pose as an intellectual, but you’re a corrupt thief’ she spits. ‘Do you have to be the stereotype of a Jew?…Muslims are not like their Jewish counterparts, who quietly got gassed and then cashed in on it…my people are crazy motherfuckers and there will be hell to pay.’

Where Give Me Everything You Have excels is in describing the raw fear a stalker can foster in their victim. Lasdun is destabilised by Nasreen’s attempts to ruin his online reputation. Like most of us, he considers himself a good person – moral, politically liberal and caring – so her accusations unsettle his self-perception. She is holding a fairground mirror up to him, reflecting back all of his anxieties and showing him something distorted, unrecognisable and grotesque. The more he ignores her, the closer she gets. ‘You think you’re clever, but your name is tarnished,’ she taunts. She veils herself in the anonymity of the internet, striking at him via reviews of his books on Amazon and the comment threads under his occasional newspaper articles. She vandalises his Wikipedia entry with childish scatalogical taunts. She emails his colleagues with unfounded allegations that he colluded with others to steal her work and sexually assault her. Like anyone else would under the circumstances, Lasdun rapidly descends into a pit of despair, rage and paranoia.

"Paranoia is a dysfunction in one’s relations with other people. It requires a societal context, and Nasreen’s incorporation of my various personal and professional associates into her campaign supplied this very efficiently…all she had to do was introduce the concept of smearing my name and furnish a few concrete example of having done so, and my anxious self-interest could be relied on to expand the process indefinitely. The calculus was simple: if a person is prepared to falsely assert X about you, then why would she not also falsely assert Y? Why, in fact, would she not assert every terrible thing under the sun? And if that person has already demonstrably reported those terrible things to your agent, your boss, your colleagues, then why might she not also be in the process of reporting them to your neighbours, your friends, your editor at this or that paper or magazine, your relatives, et cetera?"

You get the impression that Lasdun is telling us his story in an attempt to make sense of it himself: he scrutinises her words as if he’s critically assessing a work of literature, as though hoping to divine some deeper meaning as to why she made him the focal point of her malice. He frames his situation using literary references, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (an innocent knight falls prey to the seductions of a conniving temptress) and Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (an unassuming man is driven to murder by a charming sociopath). He even refers to his own debut novel, The Horned Man, a paranoid thriller where, in a freakishly prescient coincidence, a male professor is accused of sexual harassment by one of his pupils. There are also two long interludes, the first detailing a cross-country trip where he visits DH Lawrence’s house in New Mexico, the second describing a visit to Israel where Lasdun tries to come to terms with his own Judaism and the history of anti-semitism. While beautifully written, these feel tacked on, as though he is padding out his story to get the 200 pages his publisher wants.

There is no happy ending to Give Me Everything You Have, no trite moral tied up with a pretty bow. Nasreen doesn’t get caught and prosecuted (when Lasdun reports her to the police, their only action is to call her and tell her to stop, which just makes things worse). At the end of the book, she is still emailing him abuse and has even taken to leaving messages on his answerphone. However, in telling this deeply unsettling story, it feels as though Lasdun has turned the tables on his stalker. ‘You could say that I had stumbled upon a way of deploying my own preferred form of resistance: weakness as strength,’ he says towards the end of the book. ‘It didn’t make the situation any better in practical terms, but it made it fractionally more bearable. It was certainly the only kind of resistance that did me any good.’ In telling this tale, it feels as though he is giving his stalker – and us – everything he has. One only hopes that for his peace of mind, it’s enough.

Give Me Everything You Have is available now, published by Jonathan Cape

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more