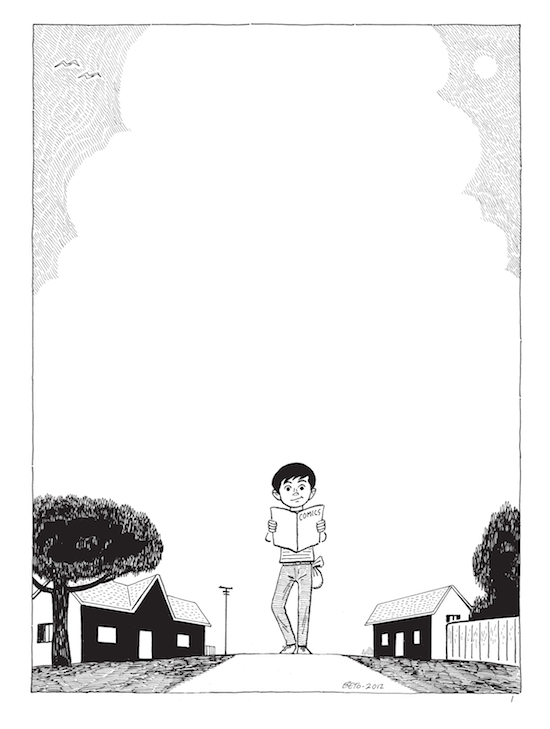

Gilbert Hernandez’s new book Marble Season is the first of his graphic novels to be published by a mainstream book publisher, Faber & Faber. A semi-autobiographical tale, it tells the story of Gilbert and his brothers’ youth, portraying the realities of growing up in a large Mexican-American family in 1960s suburban California. Like the best indie movies, Hernandez’s graphic novel subtly explores the nuances of childhood and growing up, the importance of imagination, creativity and play, as well as how sometimes this kind of creativity gets squashed by parents, by educators, and even by other kids.

Marble Season’s publication by a respected book publisher like Faber is part of the current mainstreaming of comics culture that’s been going on for the past 20 years or more, with comics artists increasingly being regular fixtures in art galleries, and graphic novels now being reviewed by mainstream newspapers. This mainstreaming has many positive aspects – with certain comic book creators finally gaining wider critical recognition as well as economic rewards, and a range of complex – and fun – artistic and literary works becoming available to the general public who might never venture into a comic book store but can now come across them in their local bookstore.

However, not everyone who encounters Marble Season on the bookshelves might know that Gilbert Hernandez is the co-creator, along with his brothers Jaime and Mario, of the ground-breaking and innovative alternative comics series Love and Rockets. Marble Season is just the latest addition to the prolific body of work he – and his brothers – have been producing since the early 1980s.

When the Hernandez Brothers self-published the first issue of Love and Rockets – it was the equivalent of a punk fanzine, but made up of all-original comics. It quickly caught the attention of Fantagraphics’ editor-in-chief Gary Groth who began publishing the series in 1981. Love and Rockets’ combination of punk rock sensibility, elements of sci-fi and fantasy, and remarkably human and complex characters and relationships garnered critical acclaim in the comics world and sometimes beyond. Fantagraphics has continued to publish the work of the Hernandez Brothers in various incarnations over the past thirty or so years. Currently Gilbert and Jaime together produce one 100-page Love and Rockets: New Stories once a year. The brothers also work on side-projects and Gilbert has been particularly prolific.

Gilbert is perhaps best-known for his Palomar stories. A kind of extended soap opera detailing the lives, loves, and interrelationships of a large cast of characters set in the South American village of Palomar. These tales feature such unforgettable characters as the vain and beautiful Pipo and her equally beautiful son, world-famous soccer star Sergio; party-girl Tonantzin whose political awakening sends her on a tragic trajectory, and fiery, hammer-wielding, voluptuous and promiscuous Luba who drags herself up from a terrifying past to become the Mayor of Palomar. The Palomar stories have extended their geographical scope, too, with Luba moving her family to Los Angeles and her life becoming intertwined with those of her half-sisters, the emotionally complex Fritz and Petra.

Gilbert too has extended his own scope and alongside the Palomar tales has created a range of other kinds of stories inspired by ‘trashy’ pop culture, monster movies, pornography, and surrealism, as well as very different stories about childhood, like The Adventures of Venus – starring Luba’s feisty but vulnerable, soccer-playing tweenage niece – and Marble Season itself.

Gilbert, it’s a pleasure to talk to you. Can you say something about how and why you started making comics?

Gilbert Hernandez: There were comics laying around the house when I was growing up and I took to the storytelling in them pretty strongly. I found simple truths in a lot of comics that I didn’t see in films or TV.

I heard your Mother was a really big fan of comics and she got you and your brothers into them, is that right?

GH: Yes. In the 1940s my Mom read comic books, in fact she was pretty obsessed with them. Unfortunately her mother didn’t approve of them and got rid of them.

What kind of comic books did your Mom read?

GH: My Mom liked a lot of different comics but strangely the two she liked the best were the C.C. Beck Captain Marvel and Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Those were her two favourites, and me and my brothers first heard about these through our Mother talking about them, though we didn’t actually see those characters until they were reprinted in the 1960s.

Captain Marvel and The Spirit seem so different in terms of subject matter to what you and Jaime write about now, but would you say they had any kind of influence on you?

GH: Yes, they influenced us in terms of those artists’ approach to storytelling, how the artists and writers deal with the characters and stories. Both C. C. Beck’s Captain Marvel and Will Eisner’s The Spirit are well-told stories and that’s the strongest influence. We liked reading superhero comics, vampire comics, horror, crime, and though there’s not much in terms of those themes in what we do, the storytelling is there.

I also read that you and Jaime were really into the Archie comic books, which are often dismissed as being really juvenile. What interested you in them?

GH: Well, we liked reading the superhero comics too but what drew us to comics most were the kids’ comic books and especially the Archie comics. In fact, in the 1960s the Archie comics were actually more hip about rock & roll than the Marvel and DC comics were; the characters dressed and acted more like how real teenagers dressed.

I remember reading an Archie comic where the characters were debating different attitudes toward the Vietnam War, going to war versus being a ‘peacenik’, and although the overarching message was ultimately patriotic, I was surprised that there was this space in what we think of as a very ‘kiddy’ comic even to debate this. And it’s interesting that even now, in Archie Comics you have an openly gay character – Kevin Keller – being shown sharing a kiss with his boyfriend and though it’s not uncontroversial, showing gay characters kiss still seems to be more of a problem in the majority of superhero comics from Marvel and DC.

GH: That was really unavoidable in the 60s, even Archie comics couldn’t avoid talking about the Vietnam war. But with Kevin Keller too, I think part of the reason Archie Comics are maybe more able to deal with gay characters is because they’re sold in supermarkets and are geared toward a wider audience. And a lot of teenage girls look at Archie Comics, whereas the mainstream superhero comics are geared mainly towards adolescent boys who might be more threatened by gay characters.

You and your brothers never seem to have been threatened by gay characters, and both you and Jaime have included male and female gay characters in your comics. Why do you think you were so comfortable doing this, as heterosexual men?

GH: Well, for me it’s because of two things. First, it’s simply a reality. I’ve known gay people – men and women – since I was a young person. To me it’s just naturalistic and realistic to portray gay characters in a humanistic light. As a young man, I knew enough gay people as people not to fear them. On the other side of the coin, I like to irritate conservatives and homophobes. I love to do that. [laughs]

You said you found simple truths in comic books that you didn’t find in film and television… What kind of simple truths do you mean?

GH: Well, let me give you an example – the American Dennis The Menace strip which is different from your British Dennis The Menace. The British Dennis is a menace because he’s a crazy maniac. In the American strip, Dennis is a 5-year-old boy who doesn’t really understand anything, but keeps trying and ends up wrecking things because of his lack of understanding. That’s why he’s a menace. Owen Fitzgerald who drew a lot of the Dennis The Menace strips brought such a humanistic element to the drawings. The comics often used the same scripts as the Dennis The Menace TV show, but because of Owen Fitzgerald’s drawing, the comic book was so much better than the TV show and made the TV show seem awkward and fake. Because of the way he drew human beings, the comic book seemed much more truthful than TV, and I’d say that about a lot of comic books as opposed to TV and movies.

Is Owen Fitzgerald’s Dennis The Menace a big influence on you?

GH: Owen Fitzgerald might be number one on my list of influences in terms of how I want to draw people – their body language and their reactions to certain situations.

How about in terms of writing?

GH: I get bits and pieces from various comic books. Superhero comics had a lot of ‘shock value’ but I got a lot from Dennis and other kids’ comic books that deal with Christian family values. Even though my comics aren’t founded on Christian family values, because these kids’ comics are based around family values and very ordinary everyday life, that’s how I learned to write away from the ‘shock value’ of superhero comics. Though, I have to say, I loved superhero comics as well and I admired Stan Lee’s writing. But kids’ comic books – another example is Charles Schulz’s Peanuts, which was very humanistic in its writing, very simple and direct and that’s what I aspire to in my writing.

You are incredibly prolific and you have told a wide variety of different kinds of stories in a variety of different genres, from porn to surrealism to sci-fi to children’s stories. Why is this?

GH: I like doing whatever interests me. It’s a challenge for me to try to make good comics out of any genre I tackle. I trust my instincts in getting me through the more difficult genres for modern readers, like violent crime or horror stories.

What is your favourite genre to tackle?

GH: People stories like in Palomar. I get to draw what I like to draw, basically people hangin’ around, and write very humanistic kinds of situations and characters. But I do also like to draw adventure stories – more in terms of drawing them than writing them – and letting my imagination go wild. But I think I’m done with the adventure stories for now. My audience likes the people stories the most and that’s what I want to concentrate on for now.

When you started Love And Rockets with your brothers did you ever imagine a ‘big’ book publisher like Faber & Faber would be interested in your work?

GH: I’m happy about it. I don’t question good fortune.

How do you feel about the current ‘mainstreaming’ of comics culture? What are the positive aspects of this situation, and do you see any potential drawbacks?

GH: Since it can be very difficult to make a living making comics, I think a cartoonist is lucky to get that type of attention. If a good cartoonist can make a living making his comics, he’ll continue to do that; the lesser insincere cartoonist that gets a lot of press will fall by the wayside eventually. And will probably be rich.

Could you talk about these rich and insincere cartoonists?

GH: [laughs] I can’t name names, but there are certain indie cartoonists who had a real knack for making their comics grab the attention of the mainstream, and have since stopped doing comics and instead work for HBO or work as screenwriters. Then again there have been some legitimate mainstream successes for indie cartoonists who passionately believe in what they’re doing and have had great luck. Matt Groening with The Simpsons and Daniel Clowes with Ghost World which was turned into a successful indie film.

Speaking of indie films, Marble Season reminds me of some of the best indie movies about everyday life. In many ways it reminds me of the subtlety of your other series about childhood, The Adventures of Venus. A lot of your comics – the Palomar and Luba stories, for example – contain a lot of emotional, sexual and violent drama – which isn’t really evident in Marble Season. Why have you decided to shift the focus to the everyday and undramatic in this work?

GH: I simply hadn’t done it in a while. I’ve been doing crime, horror and melodrama for so long now that I wanted to reconnect with readers that missed the more personal type comics I used to be known for. All of it is me; Marble Season is simply another part of me.

Comic books starring kids – like Peanuts and Dennis The Menace – often depict a very innocent and dream-like world. Marble Season, like your Venus stories, shows relationships between children as more complicated than this. A scene that struck me was when Huey and Patty have been playing and then Huey suddenly starts being quite nasty to her about preferring ‘Bozo’ to ‘Superman’; then Lana joins in and starts undermining Huey, but Patty seems to take Huey’s side. It’s really fascinating and there are scenes like this throughout the book. What do you think these kinds of interactions are all about?

GH: These are moments that happen in real life. Patty clearly likes Huey and is willing to tolerate his obliviousness in order to get close to him. Lana senses this and wants to spoil this connection because she’s left out. Later in the story Lana decides to stop trying to wedge herself in between these types of connections by simply listening instead of spoiling things in the chance that someone might connect with her.

Your book also seems to explore the strange things that kids do – the girl who eats marbles and the weird rituals of the Mad Mad Mad Mad World Club. Are these based on real experiences and why do you think they were important to include in the story?

GH: The Mad Mad Mad Mad World Club is something that happened in real life. I just thought it was a funny bit for the story when I included it. Now that I think about it, I’ve always been interested in the way males seem to need to start clubs, or cults, to keep girls out until they need them for sex. It comes from some weird immature tribal crap, I’m sure.

So it was a real club?

GH: Yeah, the guy that ran it just has a weird sense of humour. He liked to put us through these chores and then he decided he wanted us to pelt him with water-balloons. I have no idea what was in his head, I’ve never asked and he probably doesn’t remember now!

What else in the book is drawn directly from your real experiences?

GH: The Captain America play, I did that. The imaginary movie ‘Trapped Behind the Iron Curtain’. Collecting Mars Attacks cards and coming home to find my Mother had thrown them out. I still tease her about that now, those cards would be worth a lot today!

Your comics are very humanistic and deal with everyday life but – unlike the kids’ comics you mention – also often deal with sexuality. Why is sex often an important theme to explore for you?

GH: Sex is the main way we exist on the planet. It’s an essential part of life.

I heard that you gave a talk a few years ago where you were critical of the way indie comics shy away from depicting sex as something enjoyable, and that indie comics seemed to have a strangely conservative approach to showing sex.

GH: Yes, I’m not sure how true that is now, but there was certainly a period of time when indie comics seemed to shy away from showing sex unless they wanted to show the embarrassment or difficulty of sex – which is all valid and certainly there can be embarrassments and disappointments in sex but that’s not the whole story. There hardly ever seemed to be stories about the joy of sex, and that’s what I thought was missing.

In your broader body of work you do seem keen on depicting the joys of sex.

GH: Yes, if it fits. Of course there are negative aspects to sex and relationships…

Many of your characters in the Love And Rockets and New Love stories seem to have pretty wild and active sex lives, Fritz for example…

GH: Yes but Fritz’s story is a depressing one. Underneath the fun she’s a sad person. But I don’t mean to imply this is a universal truth – that people who are having fun are always sad underneath the surface; that’s her story and that’s one character.

Your characters are complex and in your erotic comic book Birdland and in the Palomar stories and so on, you do show a range of sexual experiences which often do seem joyful. Why do you like to write about sex?

GH: The quick answer is that it’s there, and I’m simply not afraid to talk about it. It’s different for so many other people but it’s never been a negative with me, only when somebody’s tried to convince me that it’s a bad thing.

Have you had negative criticisms for showing sex?

GH: Not really, I used to get people criticizing me for drawing so many women with gorgeous idealized bodies, but I pointed out that I draw a lot of men with muscular bodies, washboard abs, and enormous wangs, and they never got criticized. So those criticisms have stopped now! [laughs]

I’ve had similar criticisms for the way I draw women, but as you say, people rarely complain about the idealized men I draw. Is it easy for you to be thick-skinned about comments like that?

GH: If you believe in what you’re doing, and someone criticizes that, it’s likely that they’re just coming from a different place and they’re bringing their own baggage and it’s basically projection. I try not to let it get to me.

It sounds like you have a really good attitude toward it!

GH: But it took me 30 years to get here. [laughs]

Race, ethnicity, and gender are all really interesting aspects of the story as well – the Latino male characters seem at certain points to have a lot of power, as school bullies, over the white male characters. They seem to see themselves as more masculine and act out a certain macho masculinity. Why did you want to write about ethnicity?

GH: No heavy message; in my little neighborhood group of male friends, who were mostly Latino, there was never any talk of which kind of girl you could or could not like. It was in school or from someone I didn’t know well that I would hear racist crap. If I liked a blonde girl with freckles, eyebrows were raised from the jerks. Immature cackling came with it, I recall.

Was it a struggle for you to keep hold of your creativity and sense of playfulness? Were you actively discouraged from pursuing comics by some of the adults and kids around you? Who encouraged you the most?

GH: I’m basically stubborn. If anyone disapproved of my being influenced by comics, I simply ignored them. If they didn’t know where I was coming from with comics, then they didn’t know. They weren’t interested in anything that was more creative than comics. I don’t hold sports or petty game playing as anything to hold higher than creativity. It wasn’t easy maintaining my feelings about it because the opposition was always dominant. It was the actual writers and artists of the comics and films that I liked that gave me the most encouragement; more so than anyone I knew personally.

You’ve mentioned Owen Fitzgerald’s Dennis The Menace and the Archie Comics as influences, but I also detect Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko’s influence in your work.

GH: Oh yes, and you know I loved a lot of the DC superhero comics as well, especially stuff like Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen. But Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, as well as Stan Lee – when they worked together they produced the foundation of what Marvel Comics is now. They were making good comics; it’s not a hoax!

I really love that even though you’re so famous as an alternative comics creator, you’re not shy about admitting to your love of superhero comics.

GH: Most people in my generation of alternative cartoonists grew up reading, and liking, superhero comics – that’s why we’re all here! I think it will be interesting in the future, with comics becoming more diverse and more accessible in the mainstream, there’s going to be people creating comics who never grew up reading superhero comics.

You said it was the writers and artists of the comics you liked who gave you the most encouragement in the past, what are your favourite new comics to read now?

GH: I hate to say it, but I keep going back to the work of my contemporaries, people like Charles Burns, Dan Clowes and Chester Brown. Even if they just put out one new book every few years, that’s what I get excited about. Chester Brown’s Paying For It was one of my most favourite recent graphic novels, twisted as it was. Because I’m working so much I don’t see the work of that many young cartoonists so it’s hard for me to tell which are my favourites. Maybe when I get to stick my head out of the sand I’ll be able to let you know.

So what’s next, what are you working on now?

GH: I’m finishing up Maria M., which is about Fritz and Luba’s mother. Fritz is playing her in a movie of her life within the story, and there’s going to be lots of sex and violence. [laughs]

Oh that’s good to hear. [laughs] When will we see that?

GH: Hopefully in November. I definitely want to get it out this year. So far this year my books Marble Season and Julio’s Day have come out and I think Maria M. will be a good book to end the year with.

Gilbert Hernandez’s Marble Season is out now, published by Faber & Faber