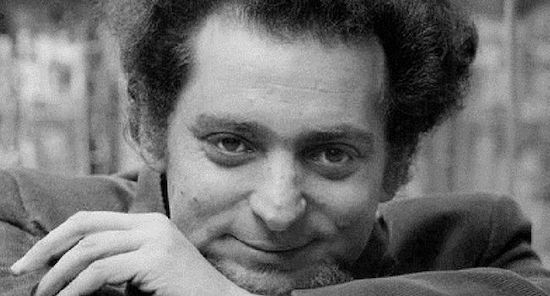

When I attempt to state what I have tried to do as a writer since I began, what occurs to me first of all is that I have never written two books of the same kind, nor ever wanted to reuse a formula, or a system, or an approach already developed in some earlier work. – Georges Perec, quoted by David Bellos in Georges Perec: A Life in Words

Georges Perec’s avowed literary mission never to write the same book twice was a tenet I took to heart as a young would-be author, and have yet to relinquish. But never writing the same book twice is not what most (if not all) publishers want to hear. Quite the contrary, most (if not all) would infinitely prefer you to repeat what has proved to be a winning formula rather than tear up the blueprint and start again, potentially losing a hard-won readership in the process.

Guidance provided to writers by well-intentioned ‘How to…’ businesses shores up this sense that even if Georges – a bona fide innovator – wasn’t shooting himself in the foot, through my contrariness, I certainly am. But I still believe there are many more types of reader than one out there, and that any one of those can be two or more types in themselves. We may read for comfort, but also for challenge; to be reassured, but also to be provoked and enlightened; to be taken by the hand and gently guided, but also to be made to battle and work for what ultimately may prove to be greater intellectual and emotional rewards. For some, the sight of divisive reviews with as many one star as five star assessments is a sign of a book worth taking on.

I was a Francophile in my second year at college when I heard about the publication in English of Perec’s mosaic of a masterpiece, Life A User’s Manual. 500-plus pages for £4.95 seemed like good value to a thrifty student, and I was soon immersed in Perec’s storytelling, discovering that in its range, the book lived up to its title. Behind the novel was an elaborate kind of scaffolding based upon the Knight’s Tour of every square of a 10 x 10 chessboard, with the board overlaying the flats and rooms of a Parisian apartment block. This appealed to the logician in me as much as Perec’s fictions – often concerning loss – hit home emotionally. Emerging from the brilliance of its denouement, it was inevitable that I would make my way through the rest of his oeuvre. But it wasn’t until I was living in France a few years later that I came to his third published work, Un Homme Qui Dort (translated by Andrew Leak as A Man Asleep).

Published in 1967, it’s slight, more novella than novel, but it made a huge impression on me. At the time that I read it – in the half-liberating, half-limiting confines of a storm-damaged cottage in Normandy with a sizeable hole in its thatched roof – I was wrestling with a similar existential malaise, the kind that seems to follow intense study in areas of knowledge that are necessarily opaque to anyone who hasn’t been channelled down the increasingly arcane and narrow academic corridors of that particular speciality. When you finally emerge and face the real world, you realise that your abstruse studies have left you no more useful to society than before you went to college, and probably rather less so (unless you remain in academia). Then, inevitably, you begin to wonder: what on earth was all that for?

After college, I had spent a year on income support, living in a bedsit in Holloway in north London, and to all intents and purposes, I was no different to the man asleep in Perec’s novella, caged in his garret room above the Rue Saint-Honoré, right in the heart of Paris, except perhaps that by way of distraction, I had the phone-in show on LBC to listen to after midnight, when I couldn’t sleep.

You are not in the habit of making diagnoses, and you don’t want to start now. What is worrying you, what is disturbing you, what is frightening you, but which now and then gives you a thrill, is not the suddenness of your metamorphosis, but precisely the opposite: the vague and heavy feeling that it isn’t a metamorphosis at all, that nothing has changed, that you’ve always been like this, even though you only now realize it fully: that thing, in the cracked mirror, is not your new face, it is just that the masks have slipped, the heat in your room has melted them, your torpor has soaked them off.

Yes, the novel is written in the second person singular – tu – and that was partly why it made such a huge impression on me. In a TV interview in 1967, Perec offered a simple explanation for its appeal: “It’s a form that mixes up the reader, the character, and the author.” A contemporary review by Roger Kleman went further, suggesting that “the second person of A Man Asleep is the grammatical form of absolute loneliness, of utter deprivation.”

Use of the second person singular made A Man Asleep a technical tour-de-force, but as David Bellos points out in his biography of Perec, “it is not the book’s most startling feature. Perec’s main innovation was to write an autobiographical novel in which almost every sentence had been written before by someone else.” Bellos carefully avoids using the word plagiarism, alternately calling what Perec does collage, borrowing, and ultimately – after a subversive technique codified by the Situationist International (of which Perec was almost certainly aware, given their Parisian Left Bank colocation) – “modified unacknowledged quotation”.

In an essay published in 1985 focusing on the musical equivalent and subtitled ‘Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative’, the composer John Oswald coined the term ‘plunderphonics’. Perhaps the zenith of plunderphonics was reached in 1996, when DJ Shadow (Josh Davis) took hip hop’s use of sampling to its logical extreme, and in Endtroducing… made an album composed almost entirely of samples from other records, the end result being music which has (almost entirely) its own air and ambience. A collage can become a musical or a fictional universe as well as an artistic one, and so it was with A Man Asleep, which contains modified and stitched together fragments of Kafka, Melville, Dante, Joyce, Diderot, Lamartine, Sartre, Le Clézio, and Barthes, among many others. In the most painstaking way, both Georges Perec and Josh Davis completely re-contextualise the appropriated fragments, blending them into a coherent whole. What in academic circles would be condemned as the lazy, unprofessional practice of plagiarism is turned into an art form. Perec himself modestly stated that “Collage … is the will to place oneself in a lineage that takes all of past writing into account. In that way, you bring your personal library to life, you reactivate your literary reserves.”

David Bellos concludes his own discussion of Perec’s modified unacknowledged quotation by suggesting that “it is as if he started to play a Victorian parlour game – ‘Narrate the Battle of Waterloo using only lines from Shakespeare’ – and discovered in it a tool for making a whole book.” As he also goes on to point out, it’s the sort of constraint OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, or ‘workshop of potential literature’) might have invented, but in fact Perec did not meet the group’s founder, Raymond Queneau, until after finishing A Man Asleep, when, no doubt in part on the strength of it, he went to lunch with the celebrated author of Zazie in the Metro, The Sunday of Life, and Pierrot Mon Ami, and found himself co-opted as a member. Queneau suggested that Oulipians are “rats who construct the labyrinth from which they plan to escape”, a notion that may well have been inspired by one of the many references to rats in Perec’s novella:

Like a prisoner, like a madman in his cell. Like a rat looking for the way out of his maze. You pace the length and breadth of Paris. Like a starving man, like a messenger delivering a letter with no address.

And then, towards the end of the book:

The rat, in his maze, is capable of truly heroic feats: by judiciously connecting the pedals he has to press in order to obtain his food to the keyboard of a piano or the console of an organ, the animal can be persuaded to give a passable rendition of “Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring”… But, poor Daedalus, there never was a maze. You bogus prisoner! your door was open all the time.

While the assembled fragments may originally have been the work of others, the story of A Man Asleep, such as it is, is certainly Perec’s own. We learn that Perec’s character is twenty-five but still a student at the Sorbonne, and assume this means that like the author, he must have spent a couple of years in conscripted military service. The man asleep has trouble sleeping, but never mentions the word insomnia. Instead his frustrated attempts to reach the realm of sleep are minutely detailed, as are his disinterested perambulations around Paris. As a result of these, the novella is also a portrait of Paris and its people in the mid-60s, prefiguring the strangely poetic repetitive description of the ‘infraordinary’ in a later work, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris. About an old man sitting immobile in the Luxembourg Gardens, Perec says,

he is mummified, perfectly still, with his heels together and his chin leaning on the knob of the walking stick that he grips tightly with both hands. … The sun describes an arc about him: perhaps his vigilance consists solely in following its shadow; he must have markers placed long in advance; his madness, if he is mad, consists in believing that he is a sundial.

While of the Île Saint-Louis, he writes,

You walk slowly, and return the way you came, sticking close to the shop-fronts: the window displays of hardware stores, electrical shops, haberdashers’, second-hand furniture dealers. You go and sit on the parapet of Pont Louis-Philippe and you watch an eddy forming and disintegrating under the arches, the funnel-shaped depression perpetually deepening and then filling up, in front of the cutwaters.

It’s an aimless chronicling of Paris, at the same time that the Situationists were developing the ideas of dérive (literally, drift; the practical application of the theory of psychogeography) and détournement (the subversion of the same capitalist system that Perec had attempted to tackle in his own fashion in his first novel, Things: a Story of the Sixties). Like Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem, Perec had recognised the chasm which existed between the ferocity of youthful idealism and the seemingly unshakeable hold consumerism had on the western world. Both tried to bridge the divide (Perec seeking to explain it, the Situationists to storm the barricades); in their different ways, Perec’s first and third books recognise how hard it is not to fall into that chasm.

Unhappiness did not swoop down on you, this was no surprise attack: more of a gradual infiltration, it insinuated itself almost ingratiatingly. It meticulously impregnated your life, your movements, the hours you keep, your room, like a long-obscured truth, or something that was staring you in the face but which you refused to recognise; tenacious and patient, subtle and unremitting, it took possession of the cracks in the ceiling, of the lines in your face in the cracked mirror, of the pack of cards; it slipped furtively into the dripping tap on the landing, it echoed in sympathy with the chimes of each quarter-hour from the bells of Saint-Roch.

Although he rarely labels it as such, Perec’s character is clearly suffering from depression, that manifold, existential malaise that likely upwards of the traditionally quoted fifth or a quarter of us all travel through, or remain within. As with Perec’s character, my own depression developed while I was a student majoring in sociology (though the existential malaise was deepened and broadened through also reading philosophy; Hegel was no help to an unhappy youth, and I was beyond the reach of Kant’s aesthetics). Taking on Guy Debord’s revelatory treatise, The Society of the Spectacle, on top of academic reading may have lifted the veils from my eyes, but it didn’t do one’s mental well-being any favours.

You are a tireless walker: every evening you emerge from the black hole of your room, from your rotting staircase, your silent courtyard, to criss-cross Paris; beyond the great pools of noise and light: Opéra, the Boulevards, the Champs Elysées, Saint-Germain, Montparnasse, you head out towards the dead city, towards Péreire or Saint-Antoine, towards Rue de Longchamp, Boulevard de l’Hôpital, Rue Oberkampf, Rue Vercingétorix.

I made the same kind of restless peregrinations across London, driven out of my own hole of a room by a depression that seemed far worse if I stayed in. “You must forget hope, enterprise, success, perseverance.” – More than occasionally, A Man Asleep reads like a report from the life and times of an earlier loner, Fernando Pessoa’s Bernardo Soares, whose own solitary confinement was detailed over long years in what would posthumously become The Book of Disquiet.

How does one tackle depression and unbearable unhappiness in fiction without leaving the reader in a similar state? How do you leaven what might otherwise be a burden? Inviting a reader to plough their way through the minutiae of a low is a big ask. It’s a challenge which can perhaps best be addressed either through the consolations of articulately rendered fellow feeling, the aesthetic pleasure of beautifully written (or rewritten) prose, or humour, whether dished out in black handfuls, absurdist dollops, or wry pinches.

The novel I went on to write about my time in France, The Edge of the Object, is a study of depression as manifested in not one but two characters. But unlike Perec’s A Man Asleep, my story starts at the point where my central character has finally taken action, and is at the foot of the climb out of his despair. Needless to say, there is no steady incline away from the state of despondency. You can be lifted for a day, and then find yourself cast back down into it for a week or more. But my central character is at least able to feel the joys of solitude and of France, and I hope if nothing else that The Edge of the Object manages to convey those. What Perec’s character and mine – both in their mid-twenties – additionally share in common in being caged by a small room is a fascination with both the objects in that room, and those beyond it. They become life rafts, buoyant things to which one clings when the waves of depression seek to drown you.

You walk the streets, looking in the gutters or in the space of variable width which separates the parked cars from the kerbside. You discover marbles, little springs, rings, coins, gloves, and on one occasion a wallet which contained a little money, identity papers, letters, and some photographs which almost made you cry.

Is it that such trinkets connect us to childhood, when every household object had its fascination, and each anchored us to our place in the world? Do we look to draw reassurance from the familiar, certitude against instability or even madness? From within his inertia, and while six socks perennially soak in a pink plastic bowl, Perec’s man asleep establishes routines, eating the same cheap meals at the same café counters, reading Le Monde from cover to cover, and playing pinball for hours on end. Without such things, without a city’s streets to tramp, the man asleep would be a hermit rather than a loner, and hermits do not have a good track record when it comes to maintaining their sanity.

Only on the last page of Perec’s novella is there a suggestion that the man asleep will resume a purposeful life. But right to the last, he refuses the easy narrative of redemption. If there is an epiphany, it is merely this:

You have learnt nothing, except that solitude teaches you nothing, except that indifference teaches you nothing: it was a lure, it was a mesmerising illusion which concealed a pitfall. You were alone and that is all there is to it and you wanted to protect yourself; you wanted to burn the bridges between you and the world once and for all. But you are such a negligible speck, and the world is such a big word: all you ever did was to drift around a city, to walk a few kilometres past façades, shopfronts, parks and embankments.

On the novella’s final page, Perec’s character is left waiting on Place Clichy for the rain to stop. He has just hinted that this paused life will be unpaused, but he does not show it.

For me, it’s one of the most memorable scenes in all of literature (which is why I attempted to replicate something of its spirit on the last page of The Edge of the Object), preceded as it is by Perec finally allowing his character a glimpse of the way out.

It is on a day like this one, a little later, a little earlier, that everything starts, that everything continues.

Stop talking like a man in a dream.

Time is not a deus ex machina or rabbit out of a hat either in this case, or in my own novel’s. The man asleep entered upon his period of abstinence from life gradually, and in the same fashion, he begins to emerge from it. Realisation is slow-dawning, and an existential crisis can only ever be processed in the time that it takes to process. To continue to live, you have to let go of the burden of living, the insoluble torment of how to and why to live, and just live, accepting that you don’t have the answers any more than anyone else does. And that can happen while waiting for the rain to stop on Place Clichy, or within the carriage of a rickety old warhorse of a British Rail train, which has come to a dead halt in a frozen landscape, accidentally offering you a perfect view of Ely Cathedral rising above the surrounding mist.

The Edge of the Object by Daniel Williams is published by Half Pint Press