‘I took all the different things and threw the shit all together’ – George Clinton

One late summer afternoon in 1989, George Clinton is sitting on a couch in a little office somewhere in the concrete labyrinth of the Warner Brothers’ building on New York’s Rockafella Center.

A mass of rainbow hair extensions and giggling, he is in buoyant mood after the previous night’s three hour funk-affirming P-Funk All Stars marathon at the Palladium on 14th Street. In fact, George could have walked straight off the stage as he attacks the refreshments he’s brought along with gusto and expounds on The Funk, prodded by the priceless pile of P-Funk albums I’ve thrust in front of him. Like any seasoned professional I’ve interviewed from Keith Richards to Captain Beefheart, George is in his element when stretching out being interviewed by an obsessed fan who happens to be writing a story about him, feeding their legend with catchphrases while occasionally opening up on more serious topics. Today it’s a walk down memory lane for a special P-Funk edition of Tommy Boy mogul Tom Silverman’s monthly tip-sheet Dance Music Report, George getting increasingly animated as the sniffing and smoking goes on.

The only time the ebullient mood he has been displaying all afternoon visibly darkens is when he picks America Eats Its Young out of my pile. If an album such as Free Your Mind… elicited fond acid-related reminisces, 1972’s epic double album casts him back to a particularly dark period in America’s history when the increasingly grotesque Vietnam war was making its presence felt on the streets in the form of irrevocably damaged returning veterans. They might have survived the war but now had to face life back in the real world, often addicted to heroin and minus a limb or two. The government didn’t seem to give a shit, especially for its black servicemen.

“Yes, this is what that’s about!” exhaled George. “No-one wanted to talk about it back then. Even the vets didn’t want anything do with it. People don’t understand what to survive is

“The Vietnam war was happening when I made that album. It was about the heroin in Vietnam. That whole war was about heroin. The Golden Triangle… But this album also reminds me of what’s happening NOW!” George bangs the table so hard the Columbian mountain he’s scaling nearly flies off the coffee table.

The Golden Triangle straddling the mountains of Myanmar, Laos and Thailand has been one of the world’s main opium-producing regions since the 1920s. It was supplying most of the world’s heroin at the time of the Vietnam War, including to the US via CIA agents with large suitcases, it has since been revealed. As the fighting in Vietnam continued and the situation became increasingly desperate, many US soldiers switched from the marijuana prevalent at the time to easily available heroin; anything to anaesthetise the unimaginable daily horror.

By 1972, with barely a third of Americans believing the US had not made a mistake sending troops to Vietnam, peace protests were sweeping the US while the troops themselves were getting increasingly disillusioned or out of control. By the seventies, although troops were being withdrawn due to overwhelming public outcry and the obvious pointlessness of the whole exercise, the conflict had spiralled into a mess of war crimes and horrific slaughter; a whole generation seemingly drafted to sure-fire death, madness, mutilation or addiction. Direct US involvement would end in August 1973 with the passing of the Case-Church Amendment by US Congress while the capture of Saigon by the North Vietnamese Army in 1975 marked the end of the war as North and South Vietnam prepared to unify after all, at a cost of 58,200 US service members’ lives.

While heroin had decimated the original Funkadelic, its fatal allure had never grasped George, who explained, “The Man With the Golden Arm cured me of ever thinking about heroin being recreation. Even with all the acid and stuff we were taking, heroin or angel dust never appealed to me at all. I did my share of coke. But with all of it, I never got to the point – other than acid. I would’ve taken acid forever if I could’ve but it stopped working after a while. You just be up all night.”

By 1971, heroin had increased its hold in the inner city black neighbourhoods. It’s now known that black troops were routinely sent on the most hazardous missions in Vietnam. Those who managed to come out alive often bore deep mental scars which manifested in various ways as they found it hard, often impossible, to settle back into normal life. Abandoned by the country they’d served, they’d come home addicted to face another kind of dangerous jungle as they were tossed aside and forgotten. The cities were teaming with dispossessed vets who had lost jobs, homes and marriages, now addicted and hustling on the streets or begging to survive. Some could only show their stumps for change.

Talking to vets on my downtown New York travels in the eighties – often inevitable if you sat in a dive bar for longer than ten minutes – these guys felt harshly dumped on by the government. When sneering cops carried out their nightly sweeps, addicted veterans were thrown in the holding cell next to the street junkies and small-time dealers.

That day I met George I had just come out of three years living in New York’s Alphabet City, where I met a cross section of local junkies, from Puerto Rican hookers and ancient bag ladies to young black guys, some who had returned from Southeast Asia nursing their habits. At the time I was writing for a Canadian magazine and did a Christmas With The Homeless piece based on the day to day scoring and survival rituals and hours spent hanging out with this cross section of forgotten city life.

I particularly remember a quiet, articulate black man in his thirties called Al, who made his dope money selling clean syringes in the shooting gallery ‘foyer’. He would tell me how he believed the ghettoes had been flooded with smack since Vietnam’s heyday as a way of keeping the people down, dazed and controllable. Earlier that decade, crack had barged in like a crazy man at a slumber party but pre-gentrification New York in the eighties was still awash with homeless people looking for a fix. Quiet, hollow-eyed and haunted-looking, the vets weren’t hard to spot. One called himself ‘Miami’ because he originally came from the city of the same name. Al told me Miami had been to Vietnam, as he never mentioned it. He was clearly disturbed and I’d be surprised if he was still around now.

The mood always lightened whenever the corner missions had been a success and the assembled started talking about music. Hiphop hadn’t really infiltrated here but they perked up when someone spotted the latest George-related album I’d unearthed on the street and my P-Funk obsession came up, talking about how they’d grown up with this music. A lovely Spanish hooker called Lucy had seen the Mothership land when she was a teenager. It was in their blood. The way Al and the regulars bantered and howled about their P-Funk experiences was like a more animated version of white guys sitting in the pub talking about the Stones. I thought about them when I was sitting with George that afternoon.

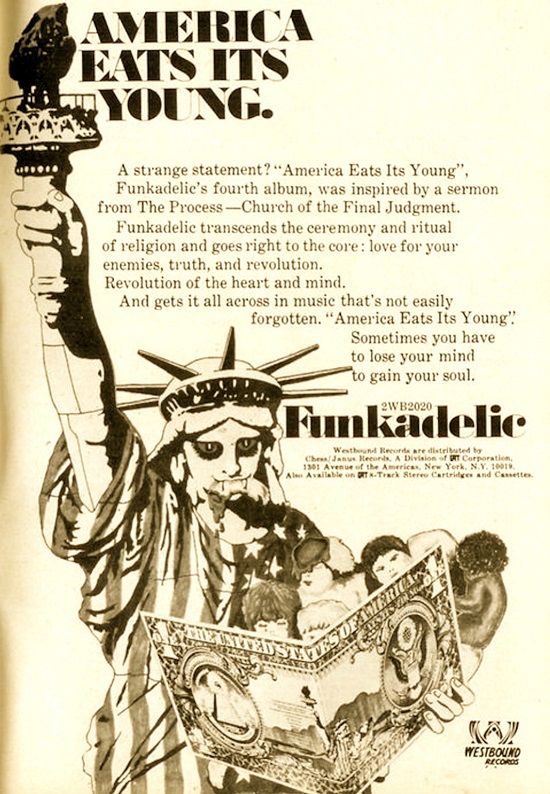

Although Maggot Brain was George’s first overtly anti-Vietnam war missive, the often misunderstood and even under-appreciated America Eats Its Young was his grand statement on how the conflict and other elements were afflicting his country. George commented on this appalling situation in his own way, starting with the title and gatefold sleeve, which he designed with Ron Scribner to replicate a one dollar bill [emphasis on the One]. Instead of laurel branches and arrows, the eagle in the Great Seal is gripping a hypodermic syringe and emaciated child while, in the middle, the Statue of Liberty is standing with evil bloodshot eyes and vampire fangs sinking into one of the babies she’s cradling, one missing half its skull and the brain. This was another George trait starting to emerge, where he liked to adapt and respray immortal American symbols and traditions to fit the concept he was brewing at the time. In this case, he was holding up America’s invincible ruler the dollar then defacing it to convey his message of money, war, heroin and death. The title is easy, Vietnam having swallowed up a whole generation of Americans.

Although the sleeve proclaimed “This album is dedicated to all the young of THE WORLD!”, the Process Church blurb offered another oblique slab of the kind of manifesto which would be abandoned by the next Funkadelic album. This particular rant, about “the agony and conflict of America” explains the album’s title with a pessimistic tint as it declares “America eats its young – maybe. But America is also our child, as now how we all have made it…America reflects to us what we have come to. The state of America is our state.” It concludes “The only way is to love our enemies!” Seventeen years after the album first appeared, George can’t resist drawing atomic dogs on the cover.

Couched in George’s most ambitiously epic production yet to befit the socially-conscious themes bristling among the love ditties and reworks, Funkadelic’s most sprawling and densely-populated album could only be a double in the grand tradition of the Stones’ Exile On Main Street, released in May the same year. I’ve always placed it among the great double albums, such as that murky basement masterpiece, Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde and Jimi’s Electric Ladyland, which all needed the extra vinyl to accommodate the gush of songs recorded. George steered the steaming hydra of America Eats Its Young into a brilliantly complete entity which now stands as one of his mightiest achievements and most potent statements.

The album was also an attempt to hit the mainstream, replacing the acid-fried landscapes of previous records with structured songs embracing the sense of concept inspired by The Who’s 1969 rock opera Tommy, even nodding to the labyrinthine arrangements of progressive rock. With his old school soul background, George knew Funkadelic had the chops to bust out of the lysergic undergrowth and clean up on more direct material, rather than the lysergic lunacy of the first three albums, which were constructed out of jams gestating on stage.

To pull off such a massive work George decided to lay off the acid, still looking quite pleased with himself when he told me, “That album was really a test to see if I could do it straight after all that acid. All the ones before that I did on acid. I wanted to see if I could make any kind of sense! The songs have got horrible names but they’re pretty straight. I did that album straight. I mean, as much as I could do it and prove to myself that I could control myself. The sixties was over, so I tried to regroup and see if I could write an album of songs that was chronological.”

Even four years later, George was still full of admiration for the Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which had now been joined by Tommy at the top of his works to aspire to. Pete Townsend’s double set telling the story of the deaf, dumb and blind boy even influenced George’s Mothership visions. With both these albums, it wasn’t so much the individual songs but the scope opened up in threading them around each other. The acid period was now officially done with and from now on George’s albums would carry some kind of loose concept.

America Eats its Young’s multi-hued complexity still polarises opinions, some finding it indulgent or impenetrable in its scope, while others call it the transitional step from the acid storms of the original band and the golden run of Funkadelic albums coming up.

It’s interesting that George has regularly cited bands as unlikely as Jethro Tull as influences at a time when black music was going through a major purple patch of landmark albums and anthemic singles being released. During the time he was working on America…, 1971 saw such milestones as Marvin Gaye’s era-reflecting What’s Goin’ On, answered by the cracked genius of Sly Stone’s chart-busting masterpiece There’s A Riot Goin’ On, the southern soul seduction of Al Green’s Let’s Stay Together, the Staple Singers’ ‘Respect Yourself’, Undisputed Truth’s ‘Smiling Faces Sometimes’ and the O’Jays’ ‘Backstabbers’. In 1972, Stevie Wonder continued his coming of age metamorphosis with Music Of My Mind and Talking Book, while George’s old boss Berry Gordy started the short-lived Black Forum offshoot to release speeches made by the likes of Dr King, Stokely Carmichael and Amiri Baraka’s fierce black nationalism poetry. But George was now firmly on his own path in his own laboratory, believing that, rather than try and outdo Motown’s new socially conscious music, he could strike into the heart of the massive white market.

“We felt that the early shit was over, the cool doos, and the hippy thing was done, with sheets and things,” he explained. “So we went right on to America Eats Its Young. That’s when we started saying, ‘Okay, let’s see if we got any brain cells left.’ Black was still popular but if you’re gonna do something you got to do it better than the black groups and better than the white groups. And Tommy and Sergeant Pepper’s, to me, was the classiest two pieces of music that I had ever seen where everything related to each other. So I wanted to do one of those kind of things.”

America Eats its Young was almost two years in the making at three studios in Toronto, Artie Fields in Detroit, Master Kraft in Memphis and London’s Olympic, the now studio-savvy George taking full production duties, using endless reels of tape until he got the desired result as tracks were built up, often using whatever the musicians were throwing in, then arranged by Bernie and George. There’s said to be a warehouse stacked with reels of out-takes, jams and sketches from the sessions which spawned America Eats Its Young, some which later went through myriad changes and stylistic alterations before their perfectionist creator deemed them fit for release. Despite being sometimes wrought into strange and wonderful shapes, classic song forms harking back to doo-wop, Motown and soul proliferate, while the blazing funk-rock is, if anything, tempered with the British rock influence which George had been embracing since the previous decade. With Bernie Worrell, he had someone who could take that element and work into the ongoing Funkadelic creative process.

As the first album recorded without recently departed original core members Eddie Hazel, Billy Nelson, Tiki Fulwood and Tawl Ross, America… is another example of George snatching victory from a potentially desperate situation as Funkadelic didn’t exist as a physical band as recording commenced. With George, Bernie the sole surviving Funkadelic and Calvin Simon relocated to Toronto, recording started in earnest at the city’s Manta studios, where George had done a deal while it was still being fitted out.

The album features the proverbial a cast of thousands befitting an epic, but also saw the gestation of a new Funkadelic nucleus including Bernie, Garry Shider, Cordell Mosson and Tyrone Lampkin, who were joined by Zachary Frazier, guitarist Harold Beane, steel guitarist Ollie Strong, James Jackson on ‘juice harp’ and full-blown string orchestra. The Toronto sessions also featured session titan Prakash John, who’d go on to become an essential part of Lou Reed’s albums and touring bands, along with Alice Cooper and many sessions.

America Eats Its Young was barbershop kids Garry Shider and Cordell Mosson’s rite of passage into Funkadelic. Somehow George had gained his devoted lifelong lieutenant along with his killer bassist band-mate Cordell ‘Boogie’ Mosson. Garry eventually became musical director, guitarist and the Starchild, earning the nickname ‘Diaper Man’ after taking the stage in an over-sized nappy. Despite cutting his musical teeth backing gospel stars, he seemed destined for the P-Funk life, his strong, soulful voice propelling many P-songs heavenwards over the next forty years.

Meanwhile, the soul revue-style vamp of ‘Philmore’ was the first major P-Funk showing from William ‘Bootsy’ Collins and his older brother Phelps, aka ‘Catfish’, who’d come straight from forging landmarks like ‘Sex Machine’ with the James Brown band. Bootsy brought his own brand of spaced out street cool to the crew. Whereas Eddie Hazel had seemed to possess a direct line to Hendrix’s soul-generated emotional flow, Bootsy flamboyantly mated Jimi’s sensual looseness with Funkadelic craziness, soon absorbing both into his star-shaded persona as funkiest bassist on the planet.

Although Bootsy’s self-composed ‘Philmore’ was his only major showing on America Eats Its Young, the bassist describes taking part in America Eats Its Young as “an awakening for me. That whole first trip, it was like, ‘Wow, this is so cool. This is what we’ve been waiting to do’. They were crazy times.”

George Clinton & The Cosmic Odyssey Of The P-Funk Empire is out now, published by Omnibus Press