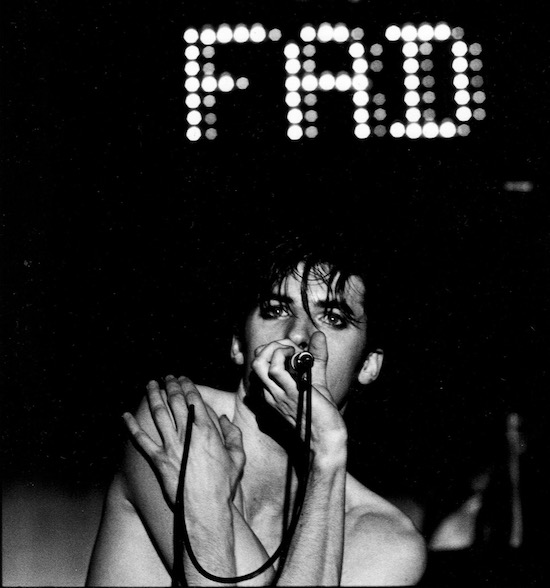

Fad Gadget

Leeds had two exceptional art schools: the Fine Art departments in the University and the Polytechnic. These were located right next to each other either side of the flyover of the inner city ring road, ‘one with a more radical political agenda, one with a more avant-gardist aesthetic agenda,’ as author Gavin Butt puts it. ‘Nowhere else in the country had that kind of art school scene,’ he claims.

Between 1974 and 1981, the young men and women who formed Gang of Four, the Mekons, Delta 5, Scritti Politti, Fad Gadget and Soft Cell studied there. Their art education – and the city they lived in – influenced their music and their notions of what being a musician in a group meant.

Butt lives in Brighton and is currently Professor of Fine Art at Northumbria University. He joins tQ from New York’s Chinatown, the day after his talk at NYU’s Colloquium for Unpopular Culture marked the book’s publication.

Describe the origins of No Machos Or Pop Stars.

Around the time I was promoted to be Professor in the early 2010s, I was speaking to colleagues who’d gone through a similar experience as me: working class background, went to university in 1980s and enjoyed the benefits of what was then a welfarist system of higher education – no fees to pay and full maintenance grant. We got to wondering if we were a dying breed given the changes which have made a university education something you need to go into debt to undertake.

Those educational conditions seemed like a world away. I wanted to go back to understand a) what we might have lost and b) what we might do in the present to change things for the better. So I saw it as an activist project really.

But it’s not a nostalgic book.

It was transparent from the first few interviews that, while people were unanimous that there was a book to be written, they all said it was a fucking shocking period to live through on so many levels. It was so dark and so violent and so depressing. They literally lived in these dank, crumbling testimonies to the failure of Modernist architecture; NF boot boys were on the streets; Peter Sutcliffe, the Yorkshire Ripper, was at large.

I also had to write about the racism even within punk communities. Julz Sale shared with me an anecdote about being on stage with Delta 5 singing ‘Anticipation’ and hearing some members of the audience singing, “repatriation is so much better”. This was not a time to wax lyrical about.

You can’t romanticise the art schools either given the sexism, misogyny and racism of art studio culture at this time. The freedoms that were there in radical art education were also exploited and abused by some white men in power.

But in the face of all that, there were progressive possibilities and that’s what I wanted to write about. Out of this gloom emerge narratives of political solidarity.

The collision of punk with art students in Leeds was key.

What I encountered when I interviewed people were narratives of disillusionment: former students had heard about the radical reputation of the Poly and all these crazy things that were going on there, they’d heard about the University and how political its Marxist and feminist approaches were. And then when they got there, it seems that these radical institutions were somehow out of step with the lived realities of Leeds at that time.

Then punk happened and they found a connection, a culture which they thought could be a way out of the impasses of the art school avant-garde agendas. I realised that punk and the Anarchy Tour rocking up at the Poly in December 1976 was a real turning point for the story I wanted to tell.

Leeds University. Photo credit: Mtaylor848. CC BY-SA 3.0

Nevertheless, in the book, the quality and popularity of the gig are disputed. Attitudes to punk itself were ambivalent from the art students.

In order to approach those times, I had to write about the fraught and fractured nature of the body politic. That punk gig was just one example of that. For some people it was a Road to Damascus moment – Green Gartside (of Scritti Politti) and some members of the Mekons and Gang of Four especially – but it’s important to say for many others it was not. The politics of Sex Pistols looked distinctly of a piece with the broader cultures of violence to some.

What comes after punk is a multi-headed appraisal of what punk put in place. Politics was part of it but even for those who found the gig so transformative, musically the Sex Pistols were just more genre, more tired rhythm and blues. I wanted to paint a picture of how inchoate this moment was and how people were struggling to make sense of a way forward.

In most punk and post-punk narratives, Leeds never seems to have a seat at the top table. Why is that?

Leeds is overshadowed by the histories of Manchester, Sheffield, Liverpool, and London of course. But let’s take the Manchester example. Leeds at the time did not have the infrastructure that Manchester had. In Manchester you’ve got a record label, Factory Records. You’ve got Tony Wilson proselytising on So It Goes on Granada TV. For the most part, the Leeds bands that got record deals got them outside of Leeds – Fast Product in Edinburgh or Mute down in London.

The scene that I write about was short-lived because most of the bands left Leeds, so their connection with Leeds has easily been forgotten. That needs to be re-remembered.

One of the key ideas of the book is that there are direct links between bands and their academic study of art and artistic practice. For example, Andy Gill’s knowledge of Manet and Gang of Four.

Andy Gill kindly let me look at some his archive. One of the things he still had was his final year dissertation on the post-impressionist Édouard Manet, in particular Le Déjeuner dans l’atelier. What Gill reads out of this painting is a representation of urban alienation, that modern society is riven by the exchange value of the commodity form, where human relations are mediated by capitalism. So he talks about how the figures in this particular composition don’t appear to relate to one another.

I find the themes Gill takes from the Manet painting to be reprised in Gang of Four songs like ‘At Home He Feels Like a Tourist’. Moreover, the disconnect between the figures in the Manet painting I see as a template for how the four members of Gang of Four think of their relationships to one another as musicians: together yet alienated from one another. They create a musical landscape in which the bass, the drums, the vocals and the guitar occupy the same soundscape but are atomised, moving around each other, at odds with themselves.

And Soft Cell seem to be the epitome of the Poly’s encouragement of provocation and its ‘intermedia’ approach.

The resources that were on offer – the sound studio, the performance space – were important but it was about the broader intermedia ethos of the pedagogy there, working between media, across media in a permissive way. That crossing of disciplinary boundaries, I see as enabling students to think about how they might cross social divisions as well. What Marc Almond (of Soft Cell) and Kris Neate – another Fine Art graduate from the Poly – were doing at their club nights at the Leeds Warehouse was trying to collage different musical and subcultural tribes together – to bring Northern Soul boys alongside people who were into Bauhaus.

Making music was only one aspect of creating and playing in groups for many of these young men and women.

What people in these bands are doing is actually a bastardised continuation of the counterculture project of the late 60s. They are aware of all the things that went wrong the first time around, but nevertheless the desires for an alternative for social and cultural transformation persist, by other means – by making music in bands. These bands represented an alternative to the Thatcherite change in politics.

No Machos Or Pop Stars: When The Leeds Art Experiment Went Punk by Gavin Butt is out now published by Duke University Press