Tony Wilson Place is the large, public-private square which introduces Manchester’s city centre if you’re walking into the city from the edge of Hulme, nestled between the canalside Haçienda apartments and the Manchester Central conference centre which in 1986 hosted Factory’s Festival of the Tenth Summer concert and this week hosted Conservative Party Conference. Look around: the large HOME cinema and arts complex is a physically domineering but altogether lonely presence in the company of a handful of chain restaurants, a dismal American-themed bar, and the typically new Manchester One Tony Wilson Place offices.

“Business space, people places” explains One Tony Wilson Place’s promotional materials, self-identifying as “grade A” with the added boast that “your neighbours are grade A too.” And should any of your neighbours be so vulgar as to end up grade B – or even grade C – then the offices (and, by extension, the square itself) are guarded by twenty-four hour security people. Friedrich Engels keeps watch too, in the form of a 1970s statue, restored and transported to the city from a Ukrainian village in 2017. A more blatant act of ‘leftwashing’ would be hard to imagine. Ideal for the busy city-centre hustler who likes their entrepreneurialism with that frisson of anti-capitalism.

In all, you might think this particular use of public space feels incongruous with the spirit of actually existing Tony Wilson – well, yes and no. When Anthony H. Wilson died of cancer in August 2007, his legacy became absorbed into a brand by the very city that was taught branding by Wilson himself. Tony Wilson Place, minted in 2015, is part of this. The long-delayed, over budget Factory arts centre is another (“anyone who is a child of the 80s will think that is a great idea” gurned George Osborne, announcing the centre in 2014). Kept in the cold by the music industry in his later years – for reasons both fair and unfair – Wilson found a new role as both hype man and alibi for the big bling Sir Richard Leese area of Manchester regeneration. In this, if Wilsonism is alive anywhere, it’s in the branding of property developers like Urban Splash, or the gentle soft-left regional populism of that other Mr Manchester, the new reigning King of the North, Andy Burnham (who was recently photographed smouldering for The Face magazine by key Manchester music photographer Kevin Cummins).

Yes, the contradictions of Tony Wilson are now Manchester’s contradictions. Here’s one: the city that beats its chest loudly about its cultural dominance, but who missed the boat on all significant pop music innovations this side of the city’s IRA bombing. As Owen Hatherley wrote of modern Manchester, “regenerated cities produce no more great pop music, great films or great art than they do industrial product. What they do produce is property developers.” This has been brought under closer inspection by recent debates about who does and who doesn’t get to benefit from Manchester’s largest funded arts institutions.

So why, then, do I continue to find much about the life of Tony Wilson so intoxicating? What Wilson achieved in the decade and a half after the Sex Pistols’ two shows at the Lesser Free Trade Hall – along with Rob Gretton, Alan Erasmus, and a legion of lesser-remembered figures, many of them women – remains a high point of cultural intervention. Here were insouciant pop philosophers changing a city on the fly between spliffs, Wilson revelling in the thrilling duality of being avant-garde music provocateur and mainstream regional telly presence. One of the tragedies of Wilson’s life was that the British television industry seldom rewards a maverick. His appearances on Channel 4’s freewheeling late-night debate show After Dark, when they briefly appear on YouTube, are exhilarating, pitched somewhere between a malevolent David Dimbleby and a slightly effete Jonathan Meades.

One of those in the orbit of that cultural intervention was Paul Morley. In the last decade of Morley’s writing life – in between books on David Bowie, Bob Dylan, Michael Jackson, the North, and rethinking the entire history of classical music – he has been researching, interviewing and writing From Manchester With Love: The Life and Opinions of Tony Wilson. Only The Factory arts centre itself has taken longer to deliver. A 600-page doorstopper, it’s the first serious attempt to contextualise Tony Wilson. Despite – or perhaps, because of – the author’s proximity to his subject, it luxuriates in the man’s contradictions and flaws, and teases out often surprising connections between Wilson and the socio-cultural currents which shaped him. I spoke to Morley over the phone on a Friday morning about the book, its anti-hero, Raymond Williams, and regeneration. So it goes.

It took ten years for you to complete this book, but really its genesis is about thirty years prior to that, with you being to some extent groomed by Tony Wilson over the years to write about his life.

It goes back to something he said to me very early on. In 1980 he had shown me, as if I was part of the family – it was very peculiar – but he took me to the chapel in Macclesfield to see Ian Curtis’ body laid in rest. A very odd, unusual thing for someone to do.

But I remember him saying to me in the car, “of course, I’m doing this because you’re writing the book.” He didn’t say what the book was – whether it was Joy Division, or Factory, or himself. It was quite an interesting part of the way he did things, and the way he rationalised that act to himself or to me, in this almost jovial way. It was very much that I had a role in all of this, and he wanted to make sure that I had all the material. I’ve always had that at the back of my mind.

There was never a moment where he said, oh, write my book. It would be more… rumours. I knew he desperately didn’t want him writing my book, or him writing my book, so it was through a process of elimination that I was the last man standing, and the only one prepared to take him on.

You’ve spent that decade also writing about other contradictory, difficult people – Michael Jackson, Bob Dylan – but I wonder whether having a greater closeness to the life of Tony Wilson presented a problem at all?

I was close to him for a while from 1976 to the early 1980s, very much so, but once I had betrayed him and moved to the NME and to London, for many years I wouldn’t see him at all. For vast acres of the 1990s I didn’t see him. He was both somebody I knew well and didn’t know at all. He was as difficult and distant a figure as anyone. Also, I started writing a book about Tony Wilson and other things kept coming up. I had this opportunity to write a book about the North, so I took the time to do that, hoping it would help this book in a way, in that it would stop me having to write too much about the North in this one. So I did that, then I had the opportunity to work with Grace Jones on her memoirs, so I took time out and did that. But every time I went back to it, I found that I hadn’t lost energy or momentum, he still seemed to pull me through.

People like Alan Erasmus came forward to speak to you, who haven’t been forthcoming at all since Wilson died.

There are people you want, and I wanted Alan more than anyone else. He’s silent, and he drifts, and he’s just wandering, and it took me a little bit of time to get him. There was a few assignations, a few wonderful meetings with him where you think you’ve got him, you’re sat at the table and then realise there’s been a mistake, he’s already had his breakfast and left the hotel. Or that he gets up and goes and you’ve lost him for a year or two. And so you track him down again.

He’s funny in that he sometimes thinks he’s being written out of history, but is very reluctant to take part in that history. I sat him down quite firmly – I don’t know whether he paid any attention – and said that it’s all very well complaining that you’ve been written out of history but you’ve got to make the history, be a part of the history, speak the history. So I put a tape recorder in front of him, and much to my surprise he didn’t get up and go after five minutes. That all took a few years, but it was something I really wanted. That partnership, that double act, it was very elusive and odd and nobody quite knew how it worked. I was always fascinated by it myself. There’s a bit in the book I quite like, somebody was trying to get hold of Alan and just had to put a piece of paper on Tony’s grave saying “can Alan Erasmus get in touch with me?”

I had no idea that Wilson had been taught by Raymond Williams at Cambridge, and you make quite a lot of the significance of that.

Well, it’s an area of the book where you feel you’re writing about a haunting, a ghostliness. The Cambridge period of Tony’s life was always very ethereal, it was a very unusual thing to have gone to Cambridge and it was definitely something that separated him from people in Manchester at the time. This idea that he’d been to Cambridge, had this life, and nobody knew what it meant but it clearly meant something because he was so different from everybody else. And you find out that he either went to lectures or communicated with Raymond Williams, one of the founding figures of a certain kind of approach to popular culture and a very innovative thinker about the role of television in people’s life. Now everybody does that about television, it’s part of everyday conversation, but back then it was very unusual to treat television like that. I was trying to piece things together like a detective with very little evidence, but this idea that a big influence over Tony was someone who approached television in this very different way.

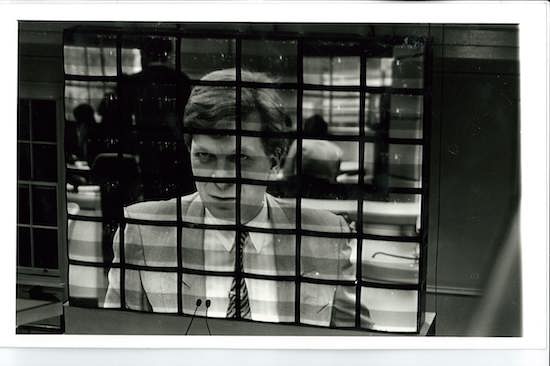

But there is this ghostliness to Tony at Cambridge. Whenever I did find any filmed evidence, Tony didn’t seem to be in it. He had some film of him just walking around in a ghostly way, a ghostly picture of him graduating. Back then, things weren’t recorded all the time, so it’s very ghostly the idea that he goes to Cambridge but there isn’t really any evidence.

I wanted to give a sense of how he came out of Cambridge a very different person to other people born in Salford and Manchester, and Raymond Williams’ writing on television seemed to point forward to the kind of television personality Tony became.

You give a potted history of situationism in the book, and very much posit that as the other great influence on Wilson when he was at Cambridge. You know as well as I do that there’s this nostalgia industrial complex around Manchester which seems to divorce these people from the actually interesting ideas – were you keen to put Wilson back into that context?

There’s a pull to take him away from that, yes. Think about the two most generalised parts of Factory – the early Joy Division part and the Happy Mondays part. It’s the latter part at the end that pulls him away and brings him very comfortably into rock’n’roll and gold discs on the wall, a very different kind of musical impresario. More conventional. He had a fascination with managers and record company moguls, but he rebuilt himself. That’s the Wilson which some people prefer, because it’s more consoling and predictable, this idea that he’s just another name in the great list of wild entertaining rock’n’roll managers. The elements that were interesting in the first place tend to be ironed out, and paved away, certainly that connection with the ideas of Situationism, and even the ideas of all art movements, and the idea of turning your life into a work of art.

That’s what was intriguing to me about Wilson when I was becoming a writer in the 1970s, that intellectual ambition and what they call pretension, which is being condescending about the idea of learning and that you would want to tell other people about your learning. That’s never been very fashionable or accepted in this country. But that was a great part of Tony’s nature, especially coming out of Manchester where you are expected to be pinned down to a certain kind of character.

Now, we had the Garretts, the Linders, the Savilles. It was an interesting period in Manchester’s history because there wasn’t much of that before or indeed after, leading to Oasis. I wanted to put into the book my idea of being a part of that history of experimental figures, those experimenting with their lives and deranging their senses, provoking incidents, creating spectacles. That’s what, at his best, Wilson was doing.

In terms of my generation, I’m a fan of that disruptor, rather than the Happy Mondays associate and the guy who set up the In The City conference. In the 1990s, he had this moment where he went for power, in a more conventional sense. That’s interesting in the overall structure of his life, yes, but I was more interested in him creating himself as a kind of work of art. The guy who had Factory Records but also worked on the telly, and in both of those ways was smuggling ideas, content, and connections to people.

I think in the early 2000s, when he was drifting a little and lacking purpose, there was a sense that that was what he was trying to find. Not the music – setting up Factory 2, 3, or 4, that all became part of the nostalgia thing – but doing weird things in Burnley or Accrington, trying to regenerate them. I found that he was struggling to find a role, for someone whose role could maybe have only lasted a certain amount of time because of what he was trying to do. But because of the person he was, he wanted to maintain that all the time. So he was trying to conceptualise, instead, the Pennines. Even though, to some extent, he settled down and was almost a caricature of himself.

I’m from that part of the world, and after reading the biography I went back and read the ludicrously titled Pennine Lancashire document, A Wish List: A Series of Consummations Devoutly to be Wished, and found the whole thing slightly tragic. Viewed from one angle, some of the insights are correct (much of what Wilson predicted would come to pass, but it would happen in West Yorkshire rather than East Lancashire), but viewed from another angle it’s just some coked up regeneration consultant taking a big fee to advocate for a fashion tower in Burnley. I found that very hard to square.

I think a lot of people around him did. To some extent, people wanted him to find another Happy Mondays, and that’s another tragedy. I think that frustrated him. So the wilfulness of him – the side that liked working with Judy and Fred Vermorel – that more obscure and battling side, it pulls through. And he’s trying to use some of his greatest hits. Saville’s involved, Philippe Starck is involved, he gets very excited about a flag. It’s so Wilsonian. But the world had moved on and he can’t find a place. He’s running out of places to go and running out of Wilsons to be.

He can be a broadcaster but it’s still not the same, because it isn’t combined with these other odd things. Now, we can see that it’s leading up to his life coming to an end and we can see the shape of it. Every time I had a conversation with him he was always grumbling about talking too much about the past, he wanted to talk about what he was doing, what he was up to. There was a tragedy about him, to some extent. All of his contemporaries in broadcasting went onto become world leaders in broadcasting – including many people he’d given their first chances to. Tony stays at the same level as a broadcaster, as much as he’s got this grandness about him. He isn’t seen to have developed. He could have become a Jeremy Paxman in one area of his life, but he sacrificed himself for this dual existence. Factory pulled down Granada, and Granada pulled down Factory.

You toyed with the idea of ‘Self Division’ as a title until an intervention from Richard Madeley – who emerges as one of the heroes of the book – and I like that as a title because there is this huge, almost collapsing weight of contradictions. The Catholic Buddhist, the socialist entrepreneur – what do you do with that as a writer?

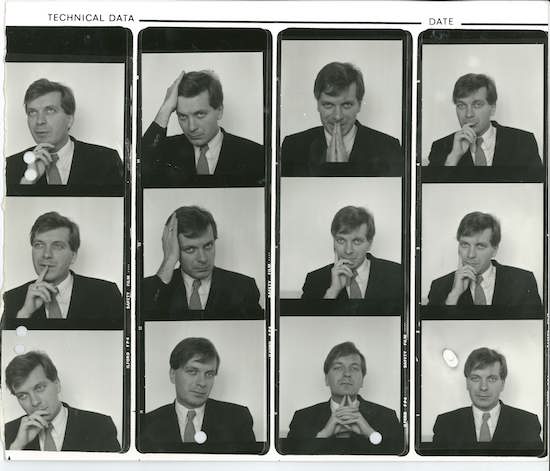

For me, that plays into how I want to write anyway. I always think that everyone and every piece of music you listen to is filled with all sorts of options and contradictions. Every person has a different view of it. For me, I can play with that idea of how difficult it is to pin anyone down anyway – let alone with a Wilson. And Wilson is such a visible, public, self-confessed example of that level of how much a person can be contradictory. This pressure to conform, to be one thing, one image, something that people can deal with in a tiny way. As much as people really appear to want to like that, when it comes to art or entertainment, when it comes to a person it can become very difficult. People don’t like it so much, they want people to conform to their own comfortable image of what a person can be. I like the idea that Wilson was constantly exploding, all the time, with his contradictions. And then there’s the part of him that’s lonely and difficult to know.

I like the image of him in The Haçienda, right in the middle of the Happy Mondays and all that, and he’s upstairs at his large desk listening to James Taylor. He’s publicly displaying himself as one thing, but he’s something else. I wanted to write a book about a complicated, unusual, very influential great Northern figure of the type we will perhaps never see again, because of how life and social media is. I wanted to revel in the amount of contradictions. I love doing that anyway, in the middle of a sentence saying, well, that isn’t quite true. I wanted to pack a lot of people around Tony Wilson too, referring to Clive James or Anthony Burgess, Colin Wilson, Alan Wilson. I’m building him up as a contradictory person from the world he was and the world that influenced him.

In the way that sometimes happens when reading books, I found that during the weekend I was reading the section about the zenith years of the late 1970s and early 1980s, I began behaving slightly more iconoclastic or bloody minded in situations. Thankfully this wore off after a few days, but I started to think that this was probably Wilson’s biggest talent. The ability to – and I don’t mean this in a sentimental way – inspire people into action. To draw things out in people. That’s an underrated, and potentially harmful, gift for a person to have. I thought it was revealing when Vini Reilly described the Durutti Column as just music he made for Tony to drive around and listen to.

Yes, and that was in the air in the 1970s, I think. Some characters showed you what you could get up to. It’s difficult to put your finger on what it is. Technology perhaps gets in the way now. Then, there was a weird freedom. You were plotting things using phone boxes, or visiting people in ad hoc ways, and that created these instant micro-societies in ways that don’t happen now. You belonged to this sect, and within that the rules were encouraging you to try things out. You realise now, with someone like Wilson, a large amount of this was rooted in how he learnt, how he had these experiences and started to create who he was, and construct a purpose in life. In one hand that was quite formal, and had a career trajectory as a broadcaster, but on the other hand was quite formless. There was no real precedent for doing that. In the classic dismal, dark 1970s, that was inspirational, it was an opening up of possibilities. You could fight against how you were appeared to have been being manipulated by banal forces. And you were prepared to be manipulated by other forces, that were much more exciting.

There’s a chapter called ‘Be Careful What You Wish For’, and that’s applicable in Manchester. A lot of what has happened to the city is not Tony Wilson’s fault, but since the destruction of the modernist 1960s city and its replacement by something else entirely, a lot of Wilson’s contradictions are now Manchester’s contradictions, which is summed up by the experience of standing in Tony Wilson Place.

At the very last minute, I added something in the book about that area. There was a meeting after Tony died, chaired by Sir Richard Leese. There was thirty or forty of us, colleagues. Coogan was there, local entrepreneurs. All the bigwigs. And the idea was how do we remember Tony Wilson? The meeting was such a flop, we needed Tony Wilson to tell us what to do. I thought it was very dreary to have a Tony Wilson Street, and I suggested that we just have Wilson, and you had to go and hunt for where this thing was, and when you got there it was a wonderful sculpture with a multimedia insight into who Wilson was. And Sir Richard Leese was so angry with me, either for not taking it seriously or for taking it too seriously. “Getting a road named after you is such an honour, such a wonderful honour!” So that became Tony Wilson Place. To me, it felt like a great taming of a spirit, more than an unleashing of his disruptive style. It’s got the arts centre there, and the statue of Engels, but it just seems too pat.

I sometimes think, one tribute to Wilson has been the remarkable amount of people that live in the city centre along the canals, apartments that look like they’ve fallen off the edge of the Haçienda building. There’s a lot of them and they look the same, but it’s a Manchester that none of us saw coming. And now, Wilson slips back into the twentieth century and becomes a figure that’s vaguely remembered. And Manchester has become the Manchester it is because of people like Wilson. But it reaches for the sky in much more banal ways now – high buildings. A very obvious way for a city to announce its self-belief. Tony Wilson was more interested in the people inside those buildings and what they were doing. Manchester has absorbed Wilson and The Haçienda into its history, and it’s very happy to have it, but if what Wilson did was a project, he achieved what he set out to achieve in making sure Manchester didn’t slip away into the past.

At that meeting at the council, the fact that there was no Wilson, it didn’t matter how many of us there was, there was nobody there to be a Wilson anymore. That part of Manchester was over. Elliot Rashman, manager of Simply Red, wanted an enormous statue of Wilson that was about the size of Beetham Tower. And in a sense, that is actually what you need. Because the truth of how wild he was, and how disruptive, it’s difficult for people to understand. It’s difficult to understand what the hell you do with the idea of Wilson, really.

From Manchester with Love: The Life and Opinions of Tony Wilson by Paul Morley is published by Faber