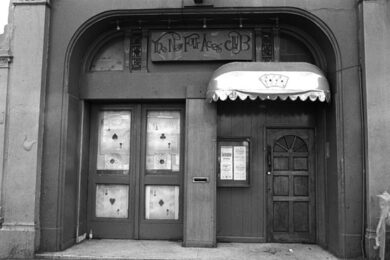

The Four Aces in Hackney opened in 1966 on the site of an old Victorian theatre built to house Robert Fossett’s Circus in 1886 on Dalston Lane. By the 1970s the club had become a centre for West Indians in cultural exile, attracting people from around the UK. In manager Newton Dunbar’s view it was successful because it offered a ‘ready-made opiate to alleviate the stresses of what was happening in the world.’

Black youths all over London began to learn about the Four Aces, including south Londoner Dennis Bovell, bass player in London-based reggae band Matumbi. Bovell has since produced such artists as The Slits, Bananarama, Fela Kuti and Linton Kwesi Johnson, but in the early 1970s he was just starting out. "Three or four of us went there in about ’71 or ’72 with our soundsystem, Sufferers Hi Fi,’ he recalls. ‘A friend had just passed his driving test and acquired his first car, so it was quite easy to get there from Wandsworth."

Sufferers were booked to play against Count Shelley, the undoubted king of sound-systems around Hackney and Stoke Newington at the time. Bovell’s young upstarts from south of the river must have been thought of as lowly challengers in comparison, so to ensure they put up a good fight, they brought with them some heavy duty equipment. "We had this column of speakers so huge that they didn’t fit through the front door," says Bovell. "My mate Errol, who was also an electrician, went out to his van and got this huge industrial screwdriver and in no time at all had the doors to the club off. It was as though we were installing a wardrobe. Newton was standing there saying, ‘You better put that thing back on.’ It meant of course that the door had to come off again afterwards to get the thing out of there."

But luck was with the pretenders that night. "Unfortunately for Shelley, but fortunately for us, he had an amplification problem that night and couldn’t play," Bovell says. "So he allowed us to play the whole night. It was a great baptism. I remember walking out of the club and my feet feeling as though they didn’t belong to me. People loved us. It was the talk of the town afterwards. ‘Did you hear what happened? Count Shelley backed out of a showdown.’ After that we were welcomed into the heavyweight sound arena. People began to listen to the Sufferers and think, ‘Hmm, that’s a formidable sound’."

These sound clashes might have involved two, three or four sound systems battling it out for prominence. Each system was meant to take it in turns to put their records on, but often impatience would win out and a sounds man – the person running the sound-system – would start playing while their rival was still playing. The battle rhetoric of the sound clash reflected the all or nothing attitude of the MCs and DJs. Aside from the odd Desmond Dekker or Bob Marley track, reggae had not made it past the hallowed gatekeepers of popular culture, national radio and television. In this way the sound systems were often the highest level of exposure that artists and DJs could aspire to. "It was a battle for Joe Public," says Bovell. "There were only a certain amount of people who listened to that stuff. You had to try and convince them your system was the best"

Sounds men who soon proved to be popular with the crowd included Fatman, of the reigning Fatman Hi Fi, in Tottenham, and Sir Coxsone, a tall, slim, studious veteran of London’s blues and sound system scene, also from Wandsworth. Coxsone became a regular at Four Aces dances: his sound was among the first to play dub. "We think of our dance public all the time," he said. "I am supposed to select music for the people to dance to, that is our job. That’s what they’re paying us for. If I, Lloyd Coxsone, am playing a disc, I like to have the majority of the people dancing. I have no other excuse than to make people enjoy themselves, and I can’t do that if I’m not fit to do my job."

"The atmosphere was electric," says Bovell. "Whether it was playing with the sound system or playing live with Matumbi I’d always had the most fun in there." Matumbi formed in Battersea in 1972. Their brand of reggae was sumptuous and tender, encouraging the rough edges of the skanking moves favoured by reggae crowds to melt away into a slow dance; music to help the hard working week fade into a distant memory.

Matumbi were the roots reggae band in England during the 1970s, and were picked by Jamaican artists such as Johnny Clarke and Pat Kelly to back them on their UK tour. "The singer would be able to voyage over from Jamaica and he’d have a ready-made band," Bovell explains. The band travelled the country and found that most cities had their own Four Aces; The Venn Street Social Club in Huddersfield – later Cleopatra’s – which opened in 1967 in the former Empress ballroom, the Nile in Moss Side, Manchester, the Bamboo Club in St Paul’s, Bristol.

Yet it was within the walls of the Four Aces that Bovell first laid eyes on the belle that would help define this particularly romantic brand of reggae. Louisa Mark was a fourteen-year-old school kid from Shepherd’s Bush in west London. In 1975 she made the journey north to take part in the weekly talent competition, where eager wannabes would fight it out over acetates provided by ‘Sir’ Lloyd Coxsone. Mark won the competition at the first attempt, and went on to triumph for ten weeks in a row. Coxsone and Bovell were impressed and took her into Gooseberry Studios in Soho to record a sumptuous cover of ‘Caught You in a Lie,’ a song originally recorded by the sax-playing soul man Robert Parker.

Matumbi provided the backing track, a heart melting slow skank. The song was a huge hit at sound system events around the UK, earning Mark celebrity status in the classrooms of Hammersmith County School. This track marked the birth of ‘lover’s rock’. In 1979, the genre earned its first big hit, with another young star discovered at the Four Aces talent show, Janet Kay, whose single ‘Silly Games’ was produced by Bovell.

In nearby Stoke Newington there was also another club that made the most of its reputation within the north London Caribbean community: Phebes. The imposing three storey gothic building had once been the hang-out of London’s celebrity gangsters, the Kray twins, who reportedly had an ‘interest’ in the place during the 60s when it was called the Regency and had a reputation as a gambling den. Back then the doors were steel plated. Jack ‘the Hat’ McVitie is said to have once confronted a doorman with a machete, while wearing shorts.

In the late 1960s a Jamaican called Vinn bought the club, and the name was changed to Phebes. The place acted as a dichotomy of UK reggae in the 1970s. In the upstairs lounge lighter reggae styles such as lover’s rock reigned, played by selectors (DJs) with names like Danny Casanova. The basement was host to sound systems that played spaced out bass-heavy dub reggae, such as Brixton’s Jah Shaka, who had a Friday night residency there from the late 1970s to the early 1980s. As if to neutralise these somewhat disparate sounds emanating from each floor, the traditional game of dominoes would dominate the tables of the ground floor bar, the clack of ivory on wood managing to pierce through the rumbling bass.

One of the most electrifying pieces of the little footage that still exists of reggae in London in the 1970s is a performance at Phebes by Roy Shirley, recorded for the 1976 documentary series Aquarius. Shirley was the man considered by some to have recorded the first rocksteady song, ‘Hold Them’, in 1966. He believed that he had been born with a gift for performance. Known as the ‘High Priest of Reggae’, he was inspired by the Salvation Army bands playing in the streets of Kingston when he was a child. His idols were American soul singers like James Brown and Solomon Burke, and like them there was something of the preacher in his performance.

In 1973 he moved to Stoke Newington, just minutes away from Phebes. It wasn’t just a change of lifestyle Shirley was after; he saw the move as providential: ‘I came to England to give my music to all the people of all races,’ he said. ‘Jonah came in the belly of the whale but I came in an aeroplane, so I must be the new Jonah. Music means more to me than just money. Music has a spiritual message, and I was born with the power to give it to the world.’

Shortly before moving to England he enjoyed a week long residency at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Shirley had a habit of upstaging and influencing the more notable soul performers that he opened for; Al Green is said to have adopted a falsetto voice technique similar to Shirley’s after the Jamaican opened for him in Jamaica. ‘Roy Shirley was a show stealer,’ says Four Aces’ Dunbar, who managed the singer in the late 70s and early 80s. ‘He was known for that and most artists after the penny dropped they decided not to have him as their warm up act.’

It is tempting to imagine who he might have upstaged on that hallowed Harlem stage. Shirley saw his north London quest as spiritual, and local promoters like Newton Dunbar may well have agreed. Here was a singer who perfectly synthesised the soul and reggae elements many had grown up with in Jamaica. Yet venues like Four Aces and Phebes were not grand theatres; compared to the Apollo’s more spacious interior, they were nooks.

During the documentary Shirley is shown before the performance working behind the counter in his record store in Stoke Newington, handing the latest reggae vinyl to some young-rebel-yoot. He takes a stroll to the Caribbean café that his record shop was attached to with a measured swagger, looking every inch the local star. The film cuts to footage of Shirley on the modest stage at Phebes. While the band plays a tight, chugging skank behind him, he is caught in the moment. At no point is he stationary: he moves around the stage with a preternatural fervency, hot-footing one-legged across it one minute, sunk to his knees with eyes tightly shut the next. There are shades of the more impassioned moments of Otis Redding, or James Brown at his most gospel. Each time he takes his performance further – pushing his voice into new territory or flinging his body to the deck to pull off some dynamic new move – the crowd, which included members of local reggae band Black Slate responds; clapping, whooping, some looking at each other in near disbelief.

In the sleeve notes to The Stax Story, a compilation of the Memphis based soul label which housed Otis Redding, the American pop essayist Greil Marcus writes about how the normality of the label represented "proof of how fine the ordinary can be." Memphis, much like Hackney, had been abandoned, but out of neglect came a determination to create something miraculous, that could still exist in the everyday. "The music that results is human scale, devoid of glamour or preening, like a simple, everyday transaction between people…who assume they can trust each other… You begin to hear ordinary people, but ordinary people stepping forward with more will, desire, vehemence, self-preservation, confidence."

The footage of Roy Shirley – the ordinary member of the neighbourhood, the local magus – suggests the same deal. Like Stax, Phebes and Club Four Aces were born out of disappearance; the Memphis label and Four Aces both took over disused cinemas to use as a base, while Phebes made its home in the place where the more crooked leaders of the white working class East End once drank. These usurped buildings – relics of a fading culture – were energised by their appropriation. Four Aces had become the hub of a brand of reggae made for London’s black community to dance to, the humdrum of the everyday transformed by schoolgirls and record shop owners metamorphosed into stars.

From CBGB to the Roundhouse is published by Marion Boyars and is available from The Book Depository. A gig to celebrate the book’s publication takes place at Catch, Kingsland Road, London, E2_ on Wednesday 8th July, featuring Wetdog, Plug, Guess What and Private Trousers, in which Burrows plays sticks… and more. Tim is a freelance music journalist living in east London.