In the late sixties, Berlin, like many European cities, was well supplied with underground clubs which

offered a variety of novelties and alternatives to disco trash. It was the beginning of September 1968

as we found ourselves in a bar called ‘Zwiebelfisch’. The live band there consisted of a keyboard player

who bashed gruesomely on his Farfisa organ, as well as a drummer who couldn’t play a tom roll but

consistently hammered out a robotic 4/4. They were called ‘Psy Free’ and had the typical funny farm

texts of those days on their leaflets. “Let’s not order anything at all, let’s just get out of here straight

away. This place is embarrassing and the music…” Monika, my girlfriend at that time, later to be my

wife, had a distinctively alternative music taste. “I look at the band, then at my skin. If I get no goose

bumps because what I’m listening to simply doesn’t interest me, so I’m leaving. Boredom is not a

luxury that means anything to me” – one of several respectable qualities which held us together for

nearly 30 years.

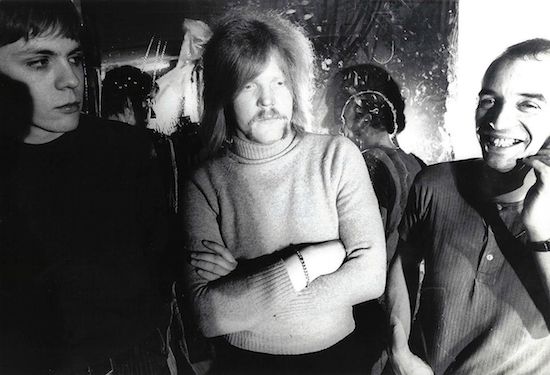

“You’re right, but check out the drummer. He could take you to the end of the Milky Way without spilling his coffee, and that is rare.” He was indeed an exception that confirmed the rule, as almost every drummer in Germany had a terrible feel for rhythm, and hardly any of them could hold a beat, let alone play anything more virtuoso or creative. It was clear to me that this drummer could provide a solid rhythmical backing for TD. “Are you married to your organ player or can we meet for a casual coffee in the next few days?” I asked him during an interval. Three days later we sat opposite one another in a pizzeria. In order to make him familiar with the slightly obscure world typical of TD conversation straight away, I asked him: “How long has it been since your parents resolved to give you the name which I do not yet know?” “What’s going on here? Is this a police interrogation or do we both have the wrong address?” He shot his reply at me, looking completely unnerved. “Do you know that your drumming is really awful?” So he’d come all the way from an outlying Berlin district just to hear insults like this? he said. “Too right,” I retorted, “and you sit there behind your badly tuned drums like a wet bag that’s been hung out to dry”. This was enough for him, and he got up and started putting on his parka. I held onto his sleeve, “But,” I said, “next weekend you and I are going to the Essener Song Days to play there, together with Frank Zappa, The Fugs and some West Coast groups at an international festival. The main part of the festival is going to be dominated by Amon Düül from Munich”, I explained, in a very relaxed way. He didn’t so much sit down again but instead rather fell back into his chair. “Just so I don’t mistake you for one of the other one and a half million inhabitants of Berlin, please could you let me know your name?” I asked. He remained nonplussed. He was Klaus, the Klaus Schulze who had been born in the Rhineland and had lived for a while in Berlin. “Hopefully you don’t intend to make your career in music; a name as exotic as Klaus Schulze would definitely get in your way.” The first laughs rang out, soon to be followed by more in that conversation. He asked who else was in the group. “At the moment it’s just you and me. I fired the others two weeks ago. We had small musical differences of opinion. I’m sure you know about such irreparable problems.” He looked at me, absolutely aghast, believing he was sitting before someone who needed professional help.

“One week before a gig in front of 10,000 people and Zappa as the main act and supported by a drummer and a – I’m sorry, what do you actually play?” “Up until now just guitar, but I can also bang

out a few tunes on the Vox organ, if I have to.” “Are you sure that you’re not completely mad? They’ll boo us off the stage after five minutes!” “My dear Mr. Schulze, let’s not make this personal, we haven’t known one another for that long.”

Because there really was only Klaus Schulze and myself in the band, I briefly explained my concept to

him. “Firstly I need the 1200 DM fee for rent and food. I’ve called the bass player and the guitarist

from Amon Düül and we’re going to do a progressive improvisation for 35 minutes and hopefully we’ll

be able to get off the stage without anything untoward happening.

The next day we met for the first time in the practice room. Because his motley collection of drums was very manageable, I explained to him that my intention was to organise three times as many drums so that it would look as though something were happening on the stage. “Might it be an idea to let me know exactly what I’m supposed to play next weekend?” he asked as he built up his kit. “That’s the wrong question Klaus; you simply leave out everything you’re not able to do, OK?” Again I gazed back into the face of a St Bernard that had been kicked for no reason. “Play your 4/4 straight through, no fancy bass drum stuff, although you can’t do that anyway, and give me the snare on the 2 and 4, no breaks, no rolls, just hammer it out until the very end; I’ll let you know when.” To me it was clear that there was no point practicing particular sequences. It was simply a matter of screwing everything together with a tiny bit of trust and reliability.

It was important that we didn’t embarrass ourselves, that was the main thing; no insecure body language or shocked reactions if things went wrong. To emit the necessary self-assurance, a measure of cheek had to make up for the missing professionalism.

The next day we met again in the rehearsal room. Due to some favourable sponsoring deals I already owned a very noisy Marshall amplifier together with two boxes which were stacked one above the other, like a sound monster – not to forget, this was still 1968. I used one of the first Fender Telecasters and a white, semi-acoustic, Gibson. Klaus’ sparse Ludwig kit was extended at short notice to include a few more tom-toms and floor-toms. The whole thing seemed ready for the stage, optically speaking.

“Schulze, start and play as if your life depends on it!” These were my last words to him as we left our

dressing room in the Grugahalle in Essen. John Weinzierl and Karas from Amon Düül were already waiting behind the closed curtain. They were two of the most hardened front-men that I’d ever met. I knew I could have sent them on stage armed with just a comb and they’d sell it as an avant-garde interlude. Very good people, and good musicians too. Just before the curtain opened, Mr. Schulze approached me again. “Do you want me to start with the snare or should I play fours on the bass

drum?” “Schulze, for the last time, I hereby knight you as the greatest drummer since Cream’s Ginger

Baker. You are literally massive, you are simply brilliant, and if you piss in your pants, the crowd will

think your brilliant sweat is running down your calves…! And now shut your mouth and get behind

your drums!” Just then, the curtain opened.

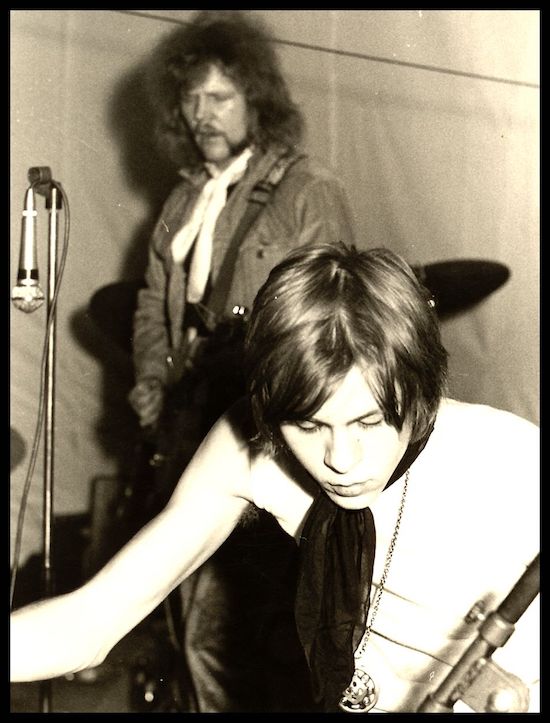

We had asked that the stage lights be turned down low, like twilight, so that we could switch on the bubble gum light show later on, which came as standard in those days. This was dramaturgy for the poor front-line city musicians, as own light shows or pyrotechnic effects were then way beyond our budget. Before any of us had played a note, a motivating heckle came from the crowd: “More boring German rubbish, get Zappa on now!” Immediately thereafter, we punished the crowd with some archaic German underground culture that went over a lot of their heads. Our lecture – high up the

scale of what one would normally be able to tolerate – was an explosion of atonal strangeness. From the bass came a hammering staccato of eighth notes, and the second guitarist had broken two strings within a few minutes, transposing his instrument’s entire tuning into an indefinable key. Whatever the hell I was supposed to be playing, all of my dials were pushed up to 10. My amplifier was emitting an orgy of feedback as I held the body of my guitar against the Marshall stack. From far away I could hear the precise beating of a snare drum, and the barely discernible tone of a bass drum that sounded more like intestinal wind discharge than a beat that one could hold on to. Everyone played for their lives, but none of us found acoustically what the others were doing.

Luckily the startling, rather creative lightshow saved the day with its then typical psychedelic effects,

taking the attention away from the racket that was tormenting the loudspeaker membranes. After a

good half-an-hour we were completely exhausted from the battle of material and I tried desperately

to catch Schulze’s eye to indicate that I wanted to play the final chord. But he hung over his drums as

though in a trance, whipping his snare so roughly, as if it were a half-dead racehorse that had to carry

him all the way through the Rocky Mountains. John, the bassist, pushed the neck of his instrument

very discreetly under his nose, so that the wild hammering became impossible. Awoken from his hardcore dream, he crashed twice on his cymbals and simply disappeared behind the stage. He’d obviously completely lost all coordination. As luck would have it, the hall music started up and played canned music, freeing us from having to experience the crowd’s reaction to our pioneering offering. A short time later, the promoter came backstage, looked at me for a moment, reached into his pocket and counted out the agreed cash for the concert into my hand. “I want to say one thing though; you’re not getting this money because you played great music – that was total rubbish: You know that, I know

that, and some of the people out there know it too”. He rolled his eyes and paused for breath.“ But

the audacity and cheek with which you pulled that off, that was really cool, and that’s why I’m giving

you this money.” He turned round and disappeared backstage without another word.

Schulze, who had meanwhile landed in the present again and had observed the scene, murmured

only: “They’re all completely bonkers here. You’re getting money which I could live on for ages just for

that noise. Oh boy was that shit.” “Mr. Schulze, be ashamed for all of us here, cos it sure takes a weight off our shoulders,” said Karas, very ironically. John added: “I’m sure Shakespeare’s shit didn’t smell of Chanel No. 5 and yet he still managed to write the brilliant “Hamlet”, know what I mean? You still have much to learn about the survival strategies of primates – but honestly, you played a great steady beat out there – that was impressive, I raise my hat to you!” The Düüls rejected the money which I offered them with the remark that they hadn’t experienced anything as funny as that for ages. Those guys were really cool, and it’s a pity that they never later found the way out of their Bavarian hermitage into the wider world – but c’est la vie – c’est la guerre!

I didn’t see Schulze for a while after that. I thought he might take on less nerve-wracking jobs after

this experience. But to my astonishment he called and asked if we could meet. “That business in Essen

kept my mind busy for ages afterwards. If we’re going to continue to make music together, we need

someone else, a third man; someone who is either a super craftsman and we wander with him into

structured music, or we continue the madness and call it art; a type of music that cannot be classified.” “And where do your personal sympathies lie?” I wanted to know his opinion. “As a drummer I could learn to play on a trapeze and play the bass drum with my tongue, but no more than that. I am not really an avant-garde type, but I wouldn’t get any satisfaction covering Stone’s songs either”. “Thanks for your openness, I know splits like these do hurt the genitals after a few minutes but, I must say, I am inclined to believe in art as a trendsetting survival strategy.” “OK, but I’m not really getting your entire musical vision, be a little clearer.”

At the next meeting, which took place under substantially more relaxed conditions, I explained my theory to him in greater detail. “It doesn’t necessarily have to function as we imagine it has to, so let’s simply throw all of our ideas overboard that we don’t need for the future. None of us wants to learn perfect craftsmanship for another ten years and then just end up as a taxi driver, know what I mean? We’ve got to look for a third member, someone who has an understanding of art, but also someone who doesn’t just want to sit around for hours discussing counterpoint or cadenzas.” Schulze had a very likeable side because he seldom spread those sorts of bad vibes, something which made co-operation impossible. At that time he had a harmony-free relationship with his well-off parents, and his permanent bitching around with angry blondes and his tendency toward the literature of Nietzsche often generated a strange tension which I found spiced up our relatively short work relationship in a very entertaining way.

For some months he stayed in an empty room at the old-style Berlin apartment which Monika and I lived in. Since he was a pleasant housemate, we were able to communicate in a very direct manner about our projects. The fact that most never came to fruition is secondary – it was fun to fill up the ideas pool to the brim, then look at it from another standpoint and empty it again, without bitterness.

I got to know the man with the exotic name of ‘Klaus Schulze’ as a likeable person whose crazed

humour was a tried and tested virtue. One day he rang our front door bell because he wasn’t able to

get his own key out of his pocket, he informed us loudly and miserably through the closed door. When

I opened it, I was faced with a very sweaty, lanky guy holding a gigantic knotted blanket tied over his

shoulders which he had just dragged up two flights of stairs. “This is still my house, Schulze,” I

welcomed him, “and I don’t much like having boulders in my house, or have you got one of your women on your conscience?” I had to laugh because he looked so Don Quixote, the good Don, who

had just lost his windmills. “Man, why don’t you try dragging nearly a hundred books up these old

Berlin stairs, you’d be pissed off too!” he snorted. “My friend, I belong to the type of primate who is

aware of the limits of their receptiveness, and I only read one book at a time, so I just can’t fathom

the situation you’re in……” I teased. When he finally sank, exhausted into his winged armchair, a gem

of a piece of furniture, he told the story of a second hand book stall which had begun to sell books in

the Kantstrasse this morning, not far from our flat. As he was passing he saw two works by Nietzsche

that he in all likelihood did not yet own. When he found out that the stallholder had just acquired an

entire collection from an old lady, Schulze wanted to search through the books to see if there were

any more. The stallholder had to rummage through over a hundred books looking for the desired

works. Schulze became impatient and nervous. When it became obvious that the bookseller couldn’t

tell the difference between the highbrow and the trivial country doctor novels, without further ado

he pulled down the sheet from the frame that covered the bookstand and placed it on the ground,

and then told the dumbfounded old man running the stall to place all of his books on the sheet, as he

wanted to buy all of them, and then take them home and sort through them himself. I really liked his

story. “All or nothing,” I thought. “Do you know what Nietzsche died of?” I asked Schulze. “I think it

was tuberculosis or syphilis, at least not hay fever!” he laughed. “When you’ve read all of that

Nietzsche junk, you’re destined to die alone because none of your two dozen blondes will understand

you anymore!”

We searched earnestly for the third member of the band who would help us realise our slightly strange

musical world view, and thereby complete the group. Of course, from my time at the academy I knew

many students who played instruments. The best were the avant-garde types in the second semester

that burnt cellos in the backyard to the backdrop of a Madrigal choir, or organised competitions with

which several recorders were blown synchronically with bicycle pumps. If that wasn’t sufficient to

draw attention, then there were always the few particularly uninhibited individuals that would begin

copulating, waiting for some particularly courageous and angry citizen to call the police to remove the

naked transgressors in handcuffs.

At one of these happenings, my attention was drawn to a heckler who came out and loudly declaimed:

“There is no nicer noise, than that of a penny dropping. And what I mean by that is that I see you’ve

realised that you’re selling fly shit as art here.” “Say now, what distinguishes you from the other fly

shitters here then?” I asked standing next to him briefly. “The fact that I cannot be enthusiastic about

activities that begin after their sell-by date, and even worse, these guys would rather play old-Berlin

songs on the barrel organ and not bother the pensioners hereabout with their unaesthetic cock.” OK,

I thought, that sounds as though he’s thought a few things through. “How do you earn your money,

should you need it; what’s your vocation?” He looked at me for a while, and, grinning, asked me

whether he was right in assuming that I was a musician, and that he had seen me playing somewhere

in a Berlin club. “The question was meant the other way round; it was about your job, not about mine,”

I asked again. “If I’m feeling really good, well, I’m a musician; otherwise, I can also be a house husband, father, lover, scrounger and playboy.”

It turned out that he had studied art and art history for several years under Joseph Beuys in the

Dusseldorf Academy – an excellent calling card. "What did your mother call you?” “Conrad, yes,

Conrad, I never had a nickname, just Conrad.” He seemed to like his name. “Yes, so what’s your

surname?” “My name is Schnitzler, and I have no idea about music; however, in all probability I will

soon become ‘famous’.” “Is the fortune-teller who told you this nonsense still alive?” I asked. “If you

know the mechanisms that the world of art is subject to, it’s all very simple,” he said restively. “Well

if you know the mechanisms so well, why are you wasting your time in backyards such as these where

you can only endure the presentations with a significant amount of pain?” “And you, what are you

doing here?” he asked, looking at me challengingly. “Well I’m definitely not here for these pubescent

second semester types. I’m looking for a location for a short music portrait which a Berlin TV broadcaster wants to make about the local underground scene.”

The next day I called Schulze and told him of the possibility to audition a guy that I actually knew very

little about, other than that he could spout a few interesting anti-establishment remarks, and who

claimed to be a musical non-musician. So we invited this Conrad Schnitzler to a session to which he

should bring his instruments. It was the 15th of October 1969. The spacious fourth floor of an old

factory building in Berlin-Kreuzberg had been turned into a rehearsal studio which a young studio

engineer had allowed us to use. He had coincidentally recently acquired a brand new Revox ¼” tape

machine with which he wanted to record the session. It was only supposed to be a test recording, just

so that everyone could begin to understand the sound we were making, which, up until now, had

remained a mystery.

I brought my guitar and my Vox organ with me, as well as an amplifier. Schulze was building up his

drum kit when the loft door opened and Conrad Schnitzler walked in. Schulze stopped his

construction, looked first at Schnitzler, then at me, sat down on his stool and stared at a carriage

similar to handcart which Schnitzler pulled behind him. Turning to me, Schulze said: “Hey old boy, do

you see what I see? I thought we wanted to get a rehearsal together here but it looks like we’re going

to be having a flea market instead. If I’m not mistaken, I can see a potato grater, a sieve with peas and

hazelnuts, several children’s rattles, a hundred year-old Adler typewriter, as well as a singed cello

with a single string – are we still in the same film?” Schulze didn’t really seem to find the scene amusing. Intuitively I felt the need to mediate, although Schnitzler’s royal collection of domestic refuse didn’t exactly make me happy either. For the first time I experienced Schulze in a bad mood, and his mood seemed to sum up the situation. “Man, I’ve dragged my whole drum kit up four flights of stairs just to be a Foley artist for a C-Movie about the Battle of Stalingrad.”

Conrad didn’t seem to be impressed by any of this. He brought a ukulele out of a briefcase and started

to wrap it in elastic bands, so that every strum produced an irritating noise. On his strange vendor’s

tray he had mounted a small number of contact microphones at different points whose signal he sent

through some echo and reverb devices, which were still very primitive at that time. Schnitzler started

to get his diverse objects going, some of them unamplified but whose sound was strange to the ear

due to the workings of the effect units. The cacophony hissed before my eyes while clattering echo

loops sounded in endless repetition, creating harsh, almost hypnotic sounds. While I took this in, I

heard behind me a crude, metallic rattling sound. When I turned round, I saw that Schulze was about

to re-pack his drum kit. I had to do something to save at least one rehearsal for posterity…

Tangerine Dream Force Majeure: The Autobiography of Edgar Froese is available from Eastgate Music Shop