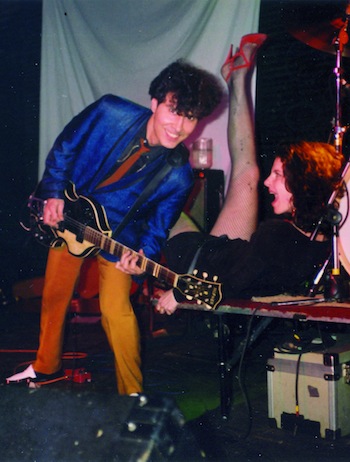

Onstage at the Orpheum Theatre in Memphis, 1978, Tav Falco, in the guise of his alter ego Eugene Baffle, chainsawed a $5 Silvertone guitar in half after performing a version of Leadbelly’s ‘Bourgeois Blues’. The combination of rock ‘n’ roll destruction and avant-garde spectacle caught the eye of attendant Big Star frontman Alex Chilton, and the pair went on to form influential ‘wreckabilly’ outfit the Panther Burns, named after the “legendary plantation in Mississippi where a panther was burned alive in a cane break”.

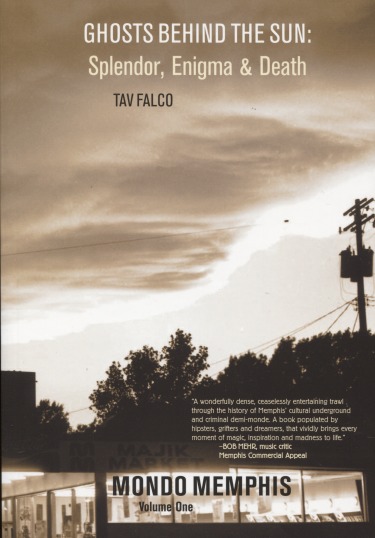

In his book, Ghosts Behind The Sun: Splendor, Enigma & Death – Mondo Memphis Volume 1, Falco traces back the city’s origins, and the rich flow of sounds that inspired him. The story is told with accounts from those who witnessed events unfold, from the civil war massacre and the treaty that formed the city, through to yellow fever outbreaks and political events that shaped Memphis as it is today.

Memphis’s extraordinary contribution to the popular music canon provides the focus of Falco’s book, as home to the Sun Records label that produced so many great artists, from Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis to less well known, but no less influential figures like Charlie Feathers. Mondo Memphis contains exhaustive interviews with everyone from the artists and those who knew them, to radio presenters and concert promoters, even Elvis’s favoured Beale Street tailor. Falco captures insights into the inner workings of the music machine, such as groundbreaking recording techniques, like the echo chamber, to early methods of promotion, and of course, the incendiary act of the live performance. In the book, Feathers told Falco: "We come from right here in the Delta, man, and that kinda music couldn’t happen nowhere else but right in here. These other people, they tickle me to death. Sometimes I sit and laugh about it. Doin’ this music here, man. They just could not do this music."

Events that captured the attention of the national press are also uncovered, as Falco delves deep into incidents like the Machine Gun Kelly kidnappings, unions securing worker’s rights, murders and underworld crime, providing a bigger picture with revealing insights into groups like the Ku Klux Klan, Hell’s Angels and various secret societies.

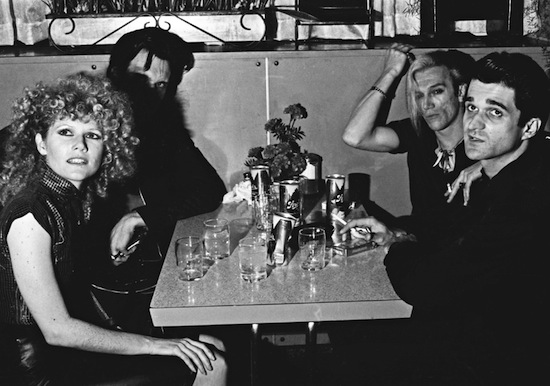

Falco was fortunate enough to attend live shows in Memphis from the mid ’60s and witnessed first-hand Delta blues, country and rock ‘n’ roll artists at events that shaped the countercultural scene that he would later play his own part in, first documenting many of the old bluesmen for the small screen as part of the Televista ‘art action’ group, before making the transition to stage himself. The early Panther Burns were inspired by everything from country, blues and La Monte Young, to the Sex Pistols, who had recently passed through on their ill-fated tour of the southern states.

More than three decades in, while many of their contemporaries are no longer with us, the ‘unapproachable’ Panther Burns remain pure and true to their original artistic vision, and can lay as good a claim as any to being the last “psychedelic backwoods ballroom band” standing.

The Quietus caught up with the self-styled ‘Beale St. Bopper of Bluff City’ via Skype on topics covered in Mondo Memphis, which Falco describes as “a long winter’s read". When we spoke Tav was back home visiting family “about a couple of hundred miles from Memphis, between Little Rock, Arkansas, and the Texan border, a little railroad town here out in the backwoods, where I grew up”. When Tav is interrupted by the arrival of a cup of tea he informs us that he will enjoy "a shot glass of bourbon" later.

How did the young Tav from Arkansas first come to visit Memphis?

Tav Falco: You had two choices if you wanted to go to the big city from Arkansas. You had Memphis, or Dallas. You could go to either of those, because we had no big cities in Arkansas.

I was drawn to Memphis for the music and the artists, film-makers and photographers working there, but mainly the music. In fact it was the Memphis country blues festivals that were produced by the Memphis Country and Blues Society, formed by turned-on psychedelic experimenters and music lovers. It was these music events at the Overton Park Shell that I would go to, starting around 1966, and they had those every year until, I think, about 1969. These events were really life changing, and they introduced so many of us to the indigenous music of Memphis, and of course you know, Memphis music is not so much Memphis, as it is the music of the country, the music of Arkansas, Mississippi, rural Tennessee, even Louisiana.

Charlie Feathers by Eugene Baffle

The book features interviews conducted over a number of years. How long were you working on the book and how did it come to be a reality?

TF: Once I was approached by Creation Books founder James Williamson and my collaborator Erik Morse, the journalist and art and music writer, who wrote Volume 2 of Mondo Memphis, I realised I had quite a backlog of research ready on audio tape and on video.

I thought it would be good to take this project on, so I took the advance and signed the contract and realised once I sat down to work that maybe this was going to be a much longer task than I had imagined; I realised that it was… monumental. But, it was too late, I had to do it. It took three years of organising research into Memphis. Three years of research and writing and we would go back to Memphis and talk to people I had known before and had not known before. I sat down to transcribe recordings and to organise the material and the reading, because there was a lot of research to be done outside of my own narratives, and my own experience.

So, then I had the problem; how to start the book? I didn’t know where to begin. I had everything I wanted to say, everything I wanted to cover – but how do you start? I’d never written a book before, and it hung me up for a while. That was the hardest part of the whole proces. Then it struck me: the persona of the time traveller, that time honoured literary device. Then I knew I had it, I knew I could write it; it was a matter of labour. And I had help. Gina Lee Falco helped me with the organisation, we worked together, and in fact the last six months was pretty much night and day writing on this book.

Tell us about the second volume of Mondo Memphis by Erik Morse?

TF: Well, in my opinion, Erik Morse is the most fascinating and thought provoking journalist working in America today, in the area of art, culture and philosophy. His style of writing is just totally enthralling. His knowledge and background is absolutely exceptional. He writes with the utmost authority on most any topics he chooses, but in a very discreet and humble way.

It’s totally a privilege to have been able to work with him on the Mondo Memphis book and do research with him in Memphis. You couldn’t find someone better to work with, even though we wrote two separate volumes we did research together and traded a lot of ideas.

You describe many memorable musical performances in the book. How did seeing these artists in their prime and up close on their home turf inform your career as a performer?

TF: We were witnessing a number of moving performances and this was, many of them, long before I started the Panther Burns. I had had never thought of performing on stage in that way, on the musical stage. I was a performer, kind of an actor, an alternative one, who worked in a video ‘art action’ group and a performance group that had little to do with actually making music with instruments as such. It was more of a performance – ‘art action’ you might say. We were under the influence of Antonin Artaud, primitive theatre, the San Francisco Mime Troupe, that kind of thing.

In Memphis, and anywhere an artist lives, you work with what is at hand, and what was at hand, in Memphis, was music. So these performances I saw, and we’d go out and see, you know, Albert King, Bukka White, Mississippi Fred McDowell, made a large, subliminal and a very intense mark on my consciousness and influence on my perception and thinking.

I came under the spell of the blues, especially the way black artists played. I met a number of them in Memphis, and also on a personal level, and went into their homes. I eventually began filming and making video and film and photographs with these artists; John ‘Piano Red’ Williams, Little Laura Dukes, dancer on Robert Nighthawk shows, and Van Zula Hunt, who had performed with Bessie Smith in road shows traveling across the South. The real Memphis people who had met performers in the 30s and 40s, who came to Memphis and became their friends. There was kind of an unbroken connection of the music, the black music that came upriver from New Orleans to Memphis. It had a profound influence, and then later, when we started Panther Burns. All of this early exposure, in a sense, was natural to draw from in starting the band. There had been Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and the Rolling Stones, and then there was the Panther Burns. It’s cut from the same cloth, at least in titular form.

Of your early concerts you describe the band as “not fully gelled”, and at the same time you could transform the cotton loft, where you regularly played, into a “flying saucer”…

TF: Well, we played the cotton loft shows for the first few months when we started the group, because we had little interest in playing in clubs and joints – we had our own place. And that’s how we were used to doing things. In our ‘art-action’ group in Memphis, in the underground that I worked through, we used to do things on our terms, in our own space. We didn’t consider ourselves a part of the establishment, and we didn’t really want to be.

We wanted to work outside of all of that. We wanted to come up with something different. That’s the product of thinking in the 1960s, you see: a view that we had to throw out certain ideas and conventions and start over. Like, throw out the word ‘talent’ – It doesn’t mean much, so we got rid of that. What else? Well, that’s one example, okay, another – the barriers between artists, like okay, you are a painter, and you over there, you are a musician and okay, this other person over there is an actor. And then we have someone who is a photographer, and you’re all doing different things, and you are all separated in what you do. In the ‘60s we threw out those ideas.

We broke down the barriers between the arts. That is part of our mission, part of the ideology – to try to create something new. So, you throw out a number of ideas, you throw out certain concepts, and you have to be careful because in the process of revolution you can sacrifice sometimes too much. You can sacrifice some of those things that maybe later you wish you hadn’t thrown away. Certain things, that could be of a tradition, that you may want to keep. You may find out it’s too late and you’ve already destroyed it.

Around the time you started Panther Burns, you mention encounters with members of the Gun Club, and The Cramps, who came to town to get the authentic Memphis sound for themselves (on their Alex Chilton-produced 1980 debut, Songs The Lord Taught Us), groups that were also playing blues and rock n roll, and updating it with a punk attitude…

TF: Well, The Cramps had a profound influence on the music of the Panther Burns. We were excited about their sound, and then, of course, once we saw them live, the stage performance was totally, totally over the top, totally fascinating and brilliant. Of course, I’m talking about the early Cramps. The presentation of Lux Interior changed quite a bit over time – I prefer the earlier image. But he was brilliant, of course, right the way through. Just like Elvis he was brilliant to the last moment.

What The Cramps did was true rockabilly music and some blues. They had one guitarist who didn’t know guitar much more than I did at the time (Bryan Gregory); who only knew three chords. Then they had Poison Ivy who was, and still is, very proficient as a guitarist and had pure rockabilly sound on the electric guitar. When you rub the two together you create an explosion, and I had never heard anything like that before.

Your early Panther Burns colleague Alex Chilton was also a member of Big Star. As self-confessed Anglophiles, how did you view their impact on the musical scene in Memphis?

TF: During the time they were working their influence was not as broad as it is today. I think there were listeners who were influenced by their music, but maybe not so many as there are today. [Big Star guitarist] Chris Bell travelled in England and he was into the Vox guitar sound particularly, and heavy guitars, harmonic guitars. It didn’t affect me much; It didn’t even hear that music of theirs until quite some time after I met Alex.Our group kind of formulated an aesthetic, and of course, it was much much different.

Something else you describe in the book is the Panther Burns playing with an all-girl ‘sister group’ in the ‘80s. Jack White of the White Stripes is currently touring with a girl band and a boy band, and depending on his mood he might play with one or the other each night. Had you heard about this, and what were your ideas when you were doing something similar?

TF: I hadn’t heard that Jack’s doing this, but I’m sure he’ll find that it can be rewarding. On the other hand, it might turn into a nightmare! It sort of happened with us. We put together a girl group in Memphis, the Hellcats, and Giovanna (Pizzorno, who still plays with the Panther Burns) was the first drummer in that group, so we worked together quite a bit and recorded a couple of records. We mitigated for them to record, we got them on record, but they kind of self-destructed from within. You find with most groups that go under it comes from within, rather than from without. A group has to have its own identity and its own access, and I never put it on myself to prop up. We tried to open some doors for them and work together.

In the book you said something about being bored at most rock concerts these days. What current artists are you interested in?

TV: Quite frankly, not so many. There’s Antony and the Johnsons in New York – I’m impressed with what they do. I heard their new recordings, but I haven’t seen them live in about five or six years. Their music, with their approach, with their songs, with the performance of Antony and his group: no one else is doing what they do. But not only that, aesthetically, they make uncompromised, meaningful, moving music; it’s very romantic. I met Antony after a concert in New York as he stood outside after the performance greeting members of the audience as they left the venue. He was humble, and very dedicated. I have a lot of respect for that.

Another is a group called Elysian Fields, another New York band, also elegant, brilliant song writers. A little on the gothic side… and sexy. Everything is so tasteful for this group, and so well thought out. I hope they can survive.

The book describes in great detail hundreds of years of history in Memphis. If you were to go back today and could take our readers around on a tour of some of the places mentioned, what is still standing and where would you show us?

TF: Well, Beale Street is still there, architecturally at least, for the most part. It has been a victim of urban development in the ‘60s, but about two to three buildings are still standing. A large part of downtown is architecturally still there – at least we have that, and I could take them to those places.

There’s a good book in the bibliography of my book, Beale Street Talks, A Walking Tour Down The Home Of The Blues, by Richard Rachelson. It’s a small book, but it traces every address in Beale Street, almost from after the civil war to the present. The saloons, the movie houses, the theatres and it gives you the addresses, the locations, how the buildings changed, who owned the buildings, what businesses were there, doctor’s offices, everything, it’s really a great little book. That’s where I would take them, and I would take them with that book. With blues and rock ‘n’ roll, Memphis was the great contributor, if not the innovator, and is pretty much the founding place for that music. This is where I would take somebody.

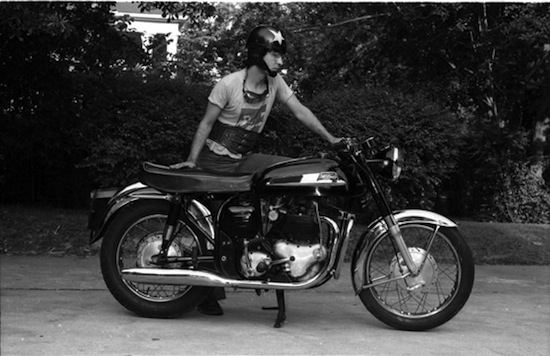

Header image, Tav Falco and Norton, by William J. Eggleston

Ghosts Behind The Sun is out now, published by Creation Books

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more